Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to the Asian Collections at the International Institute of Social History

Guide to the Asian Collections at the International Institute of Social History Emile Schwidder & Eef Vermeij (eds) Guide to the Asian Collections at the International Institute of Social History Emile Schwidder Eef Vermeij (eds) Guide to the Asian Collections at the International Institute of Social History Stichting beheer IISG Amsterdam 2012 2012 Stichting beheer IISG, Amsterdam. Creative Commons License: The texts in this guide are licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 license. This means, everyone is free to use, share, or remix the pages so licensed, under certain conditions. The conditions are: you must attribute the International Institute of Social History for the used material and mention the source url. You may not use it for commercial purposes. Exceptions: All audiovisual material. Use is subjected to copyright law. Typesetting: Eef Vermeij All photos & illustrations from the Collections of IISH. Photos on front/backcover, page 6, 20, 94, 120, 92, 139, 185 by Eef Vermeij. Coverphoto: Informal labour in the streets of Bangkok (2011). Contents Introduction 7 Survey of the Asian archives and collections at the IISH 1. Persons 19 2. Organizations 93 3. Documentation Collections 171 4. Image and Sound Section 177 Index 203 Office of the Socialist Party (Lahore, Pakistan) GUIDE TO THE ASIAN COLLECTIONS AT THE IISH / 7 Introduction Which Asian collections are at the International Institute of Social History (IISH) in Amsterdam? This guide offers a preliminary answer to that question. It presents a rough survey of all collections with a substantial Asian interest and aims to direct researchers toward historical material on Asia, both in ostensibly Asian collections and in many others. -

London Elections

London Local Elections 2018 – Time to Raise the Red Flag? On May 3rd Londoners in the capital’s 32 boroughs* will have the chance to decide who runs their local services for the next four years. Labour is widely expected to make significant gains and tighten its political hold on the city. This has big implications for development and housing delivery in the capital. Many of the incoming, first-time Labour councillors are likely to be from the far left of the party and view the private sector with hostility. Given that it is private developers that build the bulk of London’s new homes, if these political purists want to deliver more than hot air for their constituents they may soon find themselves on a collision course with reality. The Politics of London Government Labour running London is not a new phenomenon. Since The Current State of Play 1 the 1960s Labour politicians have dominated the inner London boroughs with the exception of Westminster and Last local elections - 2014: Kensington & Chelsea. The richer, outer suburban boroughs • Labour controls 20 boroughs 4 of like Bromley, Kingston and Richmond have traditionally which have directly elected mayors voted Tory. This is known as the “Donut” effect. The arrival – Hackney, Lewisham, Newham and of the Liberal Democrats in the 1980s shook up the model Tower Hamlets. when they won in places like Southwark, Richmond and • Conservatives nine. Sutton but the general principle still applies. • Liberal Democrats one. • In Havering no group has overall Indeed the last time the Conservatives controlled a majority control. -

RF177.Pdf (Redflag.Org.Au)

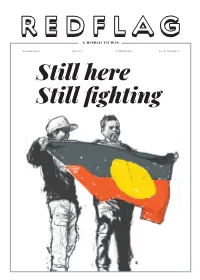

A WORLD TO WIN REDFLAG.ORG.AU ISSUE #177 19 JANUARY 2021 $3 / $5 (SOLIDARITY) Still here Still fi ghting REDFLAG | 19 JANUARY 2021 PUBLICATION OF SOCIALIST ALTERNATIVE REDFLAG.ORG.AU 2 Red Flag Issue # 177 19 January 2021 ISSN: 2202-2228 Published by Red Flag Support the Press Inc. Trades Hall 54 Victoria St Carlton South Vic 3053 [email protected] Christmas Island (03) 9650 3541 Editorial committee Ben Hillier Louise O’Shea Daniel Taylor Corey Oakley rioters James Plested Simone White fail nonetheless. Some are forced to complete rehabil- Visual editor itation programs and told that when they do so their James Plested appeals will be strengthened. They do it. They fail. These are men with families in Australia. They Production are workers who were raising children. They are men Tess Lee Ack n the first week of 2021, detainees at the Christ- who were sending money to impoverished family Allen Myers mas Island Immigration Detention Centre be- members in other countries. Now, with their visas can- Oscar Sterner gan setting it alight. A peaceful protest, which celled, they have no incomes at all. This has rendered Subscriptions started on the afternoon of 5 January, had by partners and children homeless. and publicity evening escalated into a riot over the treatment Before their transportation from immigration fa- Jess Lenehan Iof hundreds of men there by Home Affairs Minister cilities and prisons on the Australian mainland, some Peter Dutton and his Australian Border Force. Four of these men could receive visits from loved ones. Now What is days later, facing down reinforced numbers of masked, they can barely, if at all, get internet access to speak to armed Serco security thugs and Australian Federal them. -

From Artist-As-Leader to Leader-As-Artist Is a Critical Examination of the Image of Contemporary Leadership and Its Roots

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UVH Repository from from from artist - as artist-as-leader - leader to to to leader leader-as-artist - as From artist-as-leader to leader-as-artist is a critical examination of - artist the image of contemporary leadership and its roots. Through the lens of modern management texts, Pieterse explores the the dutch Beat poet and performer link between contemporary management speak and the artistic critique of the avant-garde movements of the 1950s in the Netherlands, simon Vinkenoog as exemplar of leadership focusing specifically on the Dutch Fiftiers group, the Cobra movement and 1960s countercultural activism. Subsequently, a neo- in contemporary organizations management discourse is generated whereby the figure of the artist becomes the model for the modern leader: charismatic, visionary, intuitive, mobile, creative, cooperative, open to taking risks and strong at networking. Such a discourse appeals to the values of self- actualization, freedom, authenticity and “knowledge deriving from personal experience” (Boltanski and Chiapello 2007: 113), the very values of the artistic critique that have been absorbed into modern- day capitalism. Pieterse explores this transformation of the artistic critique into contemporary leadership rhetoric by unfolding the life and work of ISBN 978-90-818047-1-4 the Dutch Beat poet and performer Simon Vinkenoog, a highly influential leader in the artistic critique. In doing so he examines the dilemmas, paradoxes and contradictions present within contemporary leadership. Vincent Pieterse is a Program Director at de Baak Management Centre, one of the largest management training institutes in the Vincent Pieterse NUR 600 Netherlands. -

Sylvia Pankhurst's Sedition of 1920

“Upheld by Force” Sylvia Pankhurst’s Sedition of 1920 Edward Crouse Undergraduate Thesis Department of History Columbia University April 4, 2018 Seminar Advisor: Elizabeth Blackmar Second Reader: Susan Pedersen With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardor alternated between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that the one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse. – George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1872 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 The End of Edwardian England: Pankhurst’s Political Development ................................. 12 After the War: Pankhurst’s Collisions with Communism and the State .............................. 21 Appealing Sedition: Performativity of Communism and Suffrage ....................................... 33 Prison and Release: Attempted Constructions of Martyrology -

Socialist Fight No.10

Socialist Fight Issue No. 10 Autumn 2012 Price: Concessions: 50p, Waged: £2.00 €3 Editorial: “Basic national loyalty and patriotism” and the US proxy war in Syria Ali Zein Al-Abidin Al-barri, summarily murdered with 14 of his men by the FSA for defending Aleppo against pro- imperialist reaction funded by Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar in another US-sponsored counter-revolution in the region Page 10-11: The Counihan-Sanchez family; Page 24: What really is imperialism? Contents a story of Cameron’s Britain. By Farooq Sulehria. Page 2: Editorial: “Basic national loyalty Page 12: FREE The MOVE 9; Ona MOVE for Page 26: Thirty Years in a Turtle-Neck and patriotism” and the US proxy war. our Children! By Cinead D and Patrick Sweater, Review by Laurence Humphries. Page 4: Rank and file conference Conway Murphy. Page 27: Revolutionary communist at Hall 11th August, By Laurence Humphries. Page 13: Letters page, The French Elec- work: a political biography of Bert Ramel- Page 4: London bus drivers Olympics’ bo- tions. son, Review by Laurence Humphries. nus: Well done the drivers! - London GRL, Page 14: Response to Jim Creggan's By Ray Page 29: Queensland: Will the Unions Step On Diversions and ‘Total Victory’ By a Rising. Up? By Aggie McCallum – Australia London bus driver. Page 17: The imperialist degeneration of Page 30: LETTER FROM TPR TO LC AND Page 6: Questions from the IRPSG . sport, By Yuri Iskhandar and Humberto REPLY. Christian Armenteros and Hum- Page 7: REPORT OF THE MEETING AT THE Rodrigues. berto Rodrigues. IRISH EMBASSY 31st JULY 2012 Page 20: A materialist world-view, Face- Page 31: Cosatu – Tied to the Alliance and Page 8: Irish Left ignores plight of Irish book debate. -

Professionalization of Green Parties?

Professionalization of Green parties? Analyzing and explaining changes in the external political approach of the Dutch political party GroenLinks Lotte Melenhorst (0712019) Supervisor: Dr. A. S. Zaslove 5 September 2012 Abstract There is a relatively small body of research regarding the ideological and organizational changes of Green parties. What has been lacking so far is an analysis of the way Green parties present them- selves to the outside world, which is especially interesting because it can be expected to strongly influence the image of these parties. The project shows that the Dutch Green party ‘GroenLinks’ has become more professional regarding their ‘external political approach’ – regarding ideological, or- ganizational as well as strategic presentation – during their 20 years of existence. This research pro- ject challenges the core idea of the so-called ‘threshold-approach’, that major organizational changes appear when a party is getting into government. What turns out to be at least as interesting is the ‘anticipatory’ adaptations parties go through once they have formulated government participation as an important party goal. Until now, scholars have felt that Green parties are transforming, but they have not been able to point at the core of the changes that have taken place. Organizational and ideological changes have been investigated separately, whereas in the case of Green parties organi- zation and ideology are closely interrelated. In this thesis it is argued that the external political ap- proach of GroenLinks, which used to be a typical New Left Green party but that lacks governmental experience, has become more professional, due to initiatives of various within-party actors who of- ten responded to developments outside the party. -

Lady Sovereign Tvs Last Thursday Night to Wit- Ness the Passing of “ER” to What I’M Sure Will Be a Golden Reign in Alex Terrono Diversify Her Album, the Short Reruns

END OF AN ‘ER’(A) CAMPUS AWAY FOR BANDS THE SUMMMER? Rock out on campus and check out Eve Samborn covers moving out of town some of our very own Wash. U. talent for the summer in Forum today. in Scene. INSIDE Miss the season finale PAGE 6 PAGE 5 of “ER”? Check out Marcia McIntosh’s recap in Ca- denza. BACK PAGE Sthe independentTUDENT newspaper of Washington University in St. Louis LIFE since eighteen seventy-eightg h Vol. 130 No. 76 www.studlife.com Wednesday, April 8, 2009 STDs at WU University to fi nish construction more common than perceived on South 40 before fall move-in William Shim will also offer the South 40 a large nience store,” Carroll wrote. experience and provide basic ameni- Becca Krock Staff Reporter multipurpose room for all types of Jeremy Lai, a sophomore who ties to make living on campus more Staff Reporter uses,” Carroll wrote in an e-mail. will be the student technology coor- convenient for students. STD numbers Wohl’s residential area will form dinator for the new Wohl residential Despite such new perks of liv- After a construction period of a residential college along with area, said there are several benefi ts ing on the South 40, Thompson still The statistical prevalence of across the U.S. over a full school year, the new Rubelmann Hall and new Umrath to living there. decided to live in the Village next sexually transmitted infections on HPV 6.2 million Wohl Center and the new Umrath Hall. “I will never have to leave my year. -

The Low Countries. Jaargang 11

The Low Countries. Jaargang 11 bron The Low Countries. Jaargang 11. Stichting Ons Erfdeel, Rekkem 2003 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_low001200301_01/colofon.php © 2011 dbnl i.s.m. 10 Always the Same H2O Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands hovers above the water, with a little help from her subjects, during the floods in Gelderland, 1926. Photo courtesy of Spaarnestad Fotoarchief. Luigem (West Flanders), 28 September 1918. Photo by Antony / © SOFAM Belgium 2003. The Low Countries. Jaargang 11 11 Foreword ριστον μν δωρ - Water is best. (Pindar) Water. There's too much of it, or too little. It's too salty, or too sweet. It wells up from the ground, carves itself a way through the land, and then it's called a river or a stream. It descends from the heavens in a variety of forms - as dew or hail, to mention just the extremes. And then, of course, there is the all-encompassing water which we call the sea, and which reminds us of the beginning of all things. The English once labelled the Netherlands across the North Sea ‘this indigested vomit of the sea’. But the Dutch went to work on that vomit, systematically and stubbornly: ‘... their tireless hands manufactured this land, / drained it and trained it and planed it and planned’ (James Brockway). As God's subcontractors they gradually became experts in living apart together. Look carefully at the first photo. The water has struck again. We're talking 1926. Gelderland. The small, stocky woman visiting the stricken province is Queen Wilhelmina. Without turning a hair she allows herself to be carried over the waters. -

Red Flag Issue8 0.Pdf

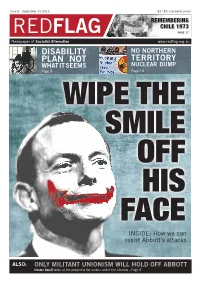

Issue 8 - September 10 2013 $3 / $5 (solidarity price) REMEMBERING FLAG CHILE 1973 RED PAGE 17 Newspaper of Socialist Alternative www.redfl ag.org.au DISABILITY NO NORTHERN PLAN NOT TERRITORY WHAT IT SEEMS NUCLEAR DUMP Page 8 Page 13 WIPE THE SMILE OFF HIS FACE INSIDE: How we can resist Abbott’s attacks ALSO: ONLY MILITANT UNIONISM WILL HOLD OFF ABBOTT Jerome Small looks at the prospects for unions under the Liberals - Page 9 2 10 SEPTEMBER 2013 Newspaper of Socialist Alternative FLAG www.redfl ag.org.au RED CONTENTS EDITORIAL 3 How Labor let the bastards in Mick Armstrong analyses the election result. 4 Wipe the smile off Abbott’s face ALP wouldn’t stop Abbo , Diane Fieldes on what we need to do to fi ght back. now it’s up to the rest of us 5 The limits of the Greens’ leftism A lot of people woke up on Sunday leader (any leader) and wait for the 6 Where does real change come from? a er the election with a sore head. next election. Don’t reassess any And not just from drowning their policies, don’t look seriously about the Colleen Bolger makes the argument for getting organised. sorrows too determinedly the night deep crisis of Laborism that, having David confront a Goliath in yellow overalls before. The thought of Tony Abbo as developed for the last 30 years, is now prime minister is enough to make the at its most acute point. Jeremy Gibson reports on a community battling to keep McDonald’s soberest person’s head hurt. -

The Actuality of Critical Theory in the Netherlands, 1931-1994 By

The Actuality of Critical Theory in the Netherlands, 1931-1994 by Nicolaas Peter Barr Clingan A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Martin E. Jay, Chair Professor John F. Connelly Professor Jeroen Dewulf Professor David W. Bates Spring 2012 Abstract The Actuality of Critical Theory in the Netherlands, 1931-1994 by Nicolaas Peter Barr Clingan Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Martin E. Jay, Chair This dissertation reconstructs the intellectual and political reception of Critical Theory, as first developed in Germany by the “Frankfurt School” at the Institute of Social Research and subsequently reformulated by Jürgen Habermas, in the Netherlands from the mid to late twentieth century. Although some studies have acknowledged the role played by Critical Theory in reshaping particular academic disciplines in the Netherlands, while others have mentioned the popularity of figures such as Herbert Marcuse during the upheavals of the 1960s, this study shows how Critical Theory was appropriated more widely to challenge the technocratic directions taken by the project of vernieuwing (renewal or modernization) after World War II. During the sweeping transformations of Dutch society in the postwar period, the demands for greater democratization—of the universities, of the political parties under the system of “pillarization,” and of -

Download Journal Sample (PDF)

2018 Geograph Autumn Vol 103 Party 3 AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL • 125 years of the Geographical Association • Twenty-five years of progress in physical geography • Geographies of mobility • Local practices in Fairtrade’s global system Geography Vol 103 Part 3 Autumn 2018 © Geography 2018 Geography Editorial Policy and Vision Geography is the Geographical Association’s flagship journal and reflects the thriving and dynamic nature of the discipline. The journal serves the ‘disciplinary community’ including academics working in geography departments in higher education institutions across the globe together with specialist teachers of the subject in schools, academies and colleges. Our role is to help ‘recontextualise’ the discipline for educational purposes. To do this, we enable readers to keep in touch with the discipline, which can be challenging but also immensely rewarding. Likewise, it is beneficial for university academics to keep in touch with the school subject and its changing educational context. Geography contributes to this process by stimulating dialogue and debate about the essential character and contribution of geography in the UK and internationally. The journal spans the breadth of human and physical geography and encourages debate about curriculum development and other pedagogical issues. The Editorial Collective welcomes articles that: • provide scholarly summaries and interpretations of current research and debates about particular aspects of geography, geography as a whole or geographical education • explore the implications