Sylvia Pankhurst's Sedition of 1920

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Records of Scotland (NRS) Women's Suffrage Timeline

National Records of Scotland (NRS) Women’s Suffrage Timeline 1832 – First petition to parliament for women’s suffrage. FAILS Great Reform Act gives vote to more men, but no women 1866 - First mass women’s suffrage petition presented to parliament by J. S. Mill MP 1867 - First women’s suffrage societies set up. Organised campaigning begins 1870 – Women’s Suffrage Bill rejected by parliament Married Women’s Property Act gives married women the right to their own property and money 1872 – Women in Scotland given the right to vote and stand for school boards 1884 – Suffrage societies campaign for the vote through the Third Reform Act. FAILS 1894 – Local Government Act allows women to vote and stand for election at a local level 1897 – National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) formed 1903 – Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) founded by Emmeline Pankhurst 1905 – First militant action. Suffragettes interrupt a political meeting and are arrested 1906 – Liberal Party wins general election 1907 – NUWSS organises the successful ‘United Procession of Women’, the ‘Mud March’ Women’s Enfranchisement Bill reaches a second reading. FAILS Qualification of Women Act: Allows election to borough and county councils Women’s Freedom League formed 1908 – Anti-suffragist Liberal MP, Herbert Henry Asquith, becomes prime minister Women’s Sunday demonstration organised by WSPU in London. Attended by 250, 000 people from around Britain Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League (WASL) founded by Mrs Humphrey Ward 1909 - Marion Wallace-Dunlop becomes the first suffragette to hunger-strike 20 October – Adela Pankhurst, & four others interrupt a political meeting in Dundee. -

From Pacifist to Anti-Fascist? Sylvia Pankhurst and the Fight Against War and Fascism

FROM PACIFIST TO ANTI-FASCIST? SYLVIA PANKHURST AND THE FIGHT AGAINST WAR AND FASCISM Erika Marie Huckestein A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved By: Susan Pennybacker Emily Burrill Susan Thorne © 2014 Erika Huckestein ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Erika Marie Huckestein: From Pacifist to Anti-Fascist? Sylvia Pankhurst and the Fight Against War and Fascism (Under the direction of Susan Pennybacker) Historians of women’s involvement in the interwar peace movement, and biographers of Sylvia Pankhurst have noted her seemingly contradictory positions in the face of two world wars: she vocally opposed the First World War and supported the Allies from the outbreak of the Second World War. These scholars view Pankhurst’s transition from pacifism to anti-fascism as a reversal or subordination of her earlier pacifism. This thesis argues that Pankhurst’s anti-fascist activism and support for the British war effort should not be viewed as a departure from her earlier suffrage and anti-war activism. The story of Sylvia Pankhurst’s political activism was not one of stubborn commitment to, or rejection of, a static succession of ideas, but one of an active engagement with changing politics, and confrontation with the new ideology of fascism, in a society still struggling to recover from the Great War. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................1 -

Claude Mckay's a Long Way from Home

Through a Black Traveler's Eyes: Claude McKay's A Long Way from Home Tuire Valkeakari Yale University Abstract: This essay analyzes Jamaican-born Claude McKay's discussion of racism(s) and nationalism(~) in his travelogue/autobiography A Long Way from Home ( 1937), in which he chronicles his sojourn in Europe and North Africa and addresses his complex relationship to the United States. Much of McKay's social analysis draws, as this essay establishes, on his observation that racism and nationalism tend to be intertwined and feed 011 each othe1: While describing his travels, McKay presents himselfas a bordercrosser who is "a bad nationalist" and an "internationalist" - a cosmopolitan whose home cannot be defined by any fixed national labels or by nationalist or racialist identity politics. This essay's dialogue with McKay's memoir ultimately reconstructs his difficult and of1-frustrated quest for democracy - the political condition that Ralph Ellison once eloquently equated with "man~· being at home in. the world." Key words: Claude McKay - nationalism - transnationalism - cosmopolitanism - race - racism - travel The way home we seek is that condition of man's being at home in the world, which is called love, and which we tenn democracy. - Ralph Elli son, "Brave Words for a Startling Occasion" I said I was born in the West Indies and lived in the United States and that I was an American, even though I was a British subject, but 1 preferred to think of myself as an internationalist. The chaoL1Sh said he didn't understand what was an internationalist. J laughed and said that an internationalist was a bad nationalist. -

The Women of Red Clydeside the Women of Red Clydeside

THE WOMEN OF RED CLYDESIDE THE WOMEN OF RED CLYDESIDE: WOMEN MUNITIONS WORKERS IN THE WEST OF SCOTLAND DURING THE FIRST WORLD WAR By MYRA BAILLIE, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School ofGraduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment ofthe Requirements for the Degree Doctor ofPhilosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Myra Baillie, September 2002 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2002) McMaster University (History) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Women ofRed Clydeside: Women Munitions Workers in the West ofScotland during the First World War. AUTHOR: Myra Baillie, B.A., M.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor R.A. Rempel NUMBER OF PAGES: x,320 11 ABSTRACT During World War One, the Clydeside region became one ofthe most important centres ofwar production in Britain. It also had one ofthe most volatile male workforces, earning it the reputation 'Red' Clydeside. Previous historical accounts have focussed on the skilled workers, debating the extent to which they were red-hot revolutionaries or narrow craft conservatives. To date, there has been no study ofthe region's large, capable, hard-working female workforce. This thesis traces the experience ofthe tens ofthousands ofwomen employed in the Clydeside munitions industry, paying particular attention to the working conditions in local factories. This thesis contributes to the long-standing historiographical arguments over the nature ofRed Clydeside by offering a new view ofthe dilution crisis which stands 11t the epicentre ofthe debate. It finds more cooperation between male and female munitions workers than has previously been recognized, and suggests that class confrontation, not craft conservatism, was at the root ofthe deportation ofthe shop steward leaders in March 1916. -

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This Collection Was the Gift of Howard J

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This collection was the gift of Howard J. Garber to Case Western Reserve University from 1979 to 1993. Dr. Howard Garber, who donated the materials in the Howard J. Garber Manuscript Collection, is a former Clevelander and alumnus of Case Western Reserve University. Between 1979 and 1993, Dr. Garber donated over 2,000 autograph letters, documents and books to the Department of Special Collections. Dr. Garber's interest in history, particularly British royalty led to his affinity for collecting manuscripts. The collection focuses primarily on political, historical and literary figures in Great Britain and includes signatures of all the Prime Ministers and First Lords of the Treasury. Many interesting items can be found in the collection, including letters from Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning Thomas Hardy, Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, King George III, and Virginia Woolf. Descriptions of the Garber Collection books containing autographs and tipped-in letters can be found in the online catalog. Box 1 [oversize location noted in description] Abbott, Charles (1762-1832) English Jurist. • ALS, 1 p., n.d., n.p., to ? A'Beckett, Gilbert A. (1811-1856) Comic Writer. • ALS, 3p., April 7, 1848, Mount Temple, to Morris Barnett. Abercrombie, Lascelles. (1881-1938) Poet and Literary Critic. • A.L.S., 1 p., March 5, n.y., Sheffield, to M----? & Hughes. Aberdeen, George Hamilton Gordon (1784-1860) British Prime Minister. • ALS, 1 p., June 8, 1827, n.p., to Augustous John Fischer. • ANS, 1 p., August 9, 1839, n.p., to Mr. Wright. • ALS, 1 p., January 10, 1853, London, to Cosmos Innes. -

Process Paper and Bibliography

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources Books Kenney, Annie. Memories of a Militant. London: Edward Arnold & Co, 1924. Autobiography of Annie Kenney. Lytton, Constance, and Jane Warton. Prisons & Prisoners. London: William Heinemann, 1914. Personal experiences of Lady Constance Lytton. Pankhurst, Christabel. Unshackled. London: Hutchinson and Co (Publishers) Ltd, 1959. Autobiography of Christabel Pankhurst. Pankhurst, Emmeline. My Own Story. London: Hearst’s International Library Co, 1914. Autobiography of Emmeline Pankhurst. Newspaper Articles "Amazing Scenes in London." Western Daily Mercury (Plymouth), March 5, 1912. Window breaking in March 1912, leading to trials of Mrs. Pankhurst and Mr. & Mrs. Pethick- Lawrence. "The Argument of the Broken Pane." Votes for Women (London), February 23, 1912. The argument of the stone: speech delivered by Mrs Pankhurst on Feb 16, 1912 honoring released prisoners who had served two or three months for window-breaking demonstration in November 1911. "Attempt to Burn Theatre Royal." The Scotsman (Edinburgh), July 19, 1912. PM Asquith's visit hailed by Irish Nationalists, protested by Suffragettes; hatchet thrown into Mr. Asquith's carriage, attempt to burn Theatre Royal. "By the Vanload." Lancashire Daily Post (Preston), February 15, 1907. "Twenty shillings or fourteen days." The women's raid on Parliament on Feb 13, 1907: Christabel Pankhurst gets fourteen days and Sylvia Pankhurst gets 3 weeks in prison. "Coal That Cooks." The Suffragette (London), July 18, 1913. Thirst strikes. Attempts to escape from "Cat and Mouse" encounters. "Churchill Gives Explanation." Dundee Courier (Dundee), July 15, 1910. Winston Churchill's position on the Conciliation Bill. "The Ejection." Morning Post (London), October 24, 1906. 1 The day after the October 23rd Parliament session during which Premier Henry Campbell- Bannerman cold-shouldered WSPU, leading to protest led by Mrs Pankhurst that led to eleven arrests, including that of Mrs Pethick-Lawrence and gave impetus to the movement. -

Revolutionary Syndicalist Opposition to the First World War: A

Re-evaluating syndicalist opposition to the First World War Darlington, RR http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0023656X.2012.731834 Title Re-evaluating syndicalist opposition to the First World War Authors Darlington, RR Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/19226/ Published Date 2012 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Re-evaluating Syndicalist Opposition to the First World War Abstract It has been argued that support for the First World War by the important French syndicalist organisation, the Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT) has tended to obscure the fact that other national syndicalist organisations remained faithful to their professed workers’ internationalism: on this basis syndicalists beyond France, more than any other ideological persuasion within the organised trade union movement in immediate pre-war and wartime Europe, can be seen to have constituted an authentic movement of opposition to the war in their refusal to subordinate class interests to those of the state, to endorse policies of ‘defencism’ of the ‘national interest’ and to abandon the rhetoric of class conflict. This article, which attempts to contribute to a much neglected comparative historiography of the international syndicalist movement, re-evaluates the syndicalist response across a broad geographical field of canvas (embracing France, Italy, Spain, Ireland, Britain and America) to reveal a rather more nuanced, ambiguous and uneven picture. -

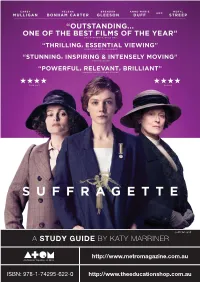

Suffragette Study Guide

© ATOM 2015 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-622-0 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Running time: 106 minutes » SUFFRAGETTE Suffragette (2015) is a feature film directed by Sarah Gavron. The film provides a fictional account of a group of East London women who realised that polite, law-abiding protests were not going to get them very far in the battle for voting rights in early 20th century Britain. click on arrow hyperlink CONTENTS click on arrow hyperlink click on arrow hyperlink 3 CURRICULUM LINKS 19 8. Never surrender click on arrow hyperlink 3 STORY 20 9. Dreams 6 THE SUFFRAGETTE MOVEMENT 21 EXTENDED RESPONSE TOPICS 8 CHARACTERS 21 The Australian Suffragette Movement 10 ANALYSING KEY SEQUENCES 23 Gender justice 10 1. Votes for women 23 Inspiring women 11 2. Under surveillance 23 Social change SCREEN EDUCATION © ATOM 2015 © ATOM SCREEN EDUCATION 12 3. Giving testimony 23 Suffragette online 14 4. They lied to us 24 ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS 15 5. Mrs Pankhurst 25 APPENDIX 1 17 6. ‘I am a suffragette after all.’ 26 APPENDIX 2 18 7. Nothing left to lose 2 » CURRICULUM LINKS Suffragette is suitable viewing for students in Years 9 – 12. The film can be used as a resource in English, Civics and Citizenship, History, Media, Politics and Sociology. Links can also be made to the Australian Curriculum general capabilities: Literacy, Critical and Creative Thinking, Personal and Social Capability and Ethical Understanding. Teachers should consult the Australian Curriculum online at http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ and curriculum outlines relevant to these studies in their state or territory. -

D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance

‘You are white – yet a part of me’: D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2019 Laura E. Ryan School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................... 3 Declaration ................................................................................................................. 4 Copyright statement ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 1: ‘[G]roping for a way out’: Claude McKay ................................................ 55 Chapter 2: Chaos in Short Fiction: Langston Hughes ............................................ 116 Chapter 3: The Broken Circle: Jean Toomer .......................................................... 171 Chapter 4: ‘Becoming [the superwoman] you are’: Zora Neale Hurston................. 223 Conclusion ............................................................................................................. 267 Bibliography ........................................................................................................... 271 Word Count: 79940 3 -

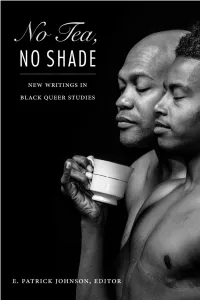

NO TEA, NO SHADE This Page Intentionally Left Blank No Tea, NO SHADE

NO TEA, NO SHADE This page intentionally left blank No Tea, NO SHADE New Writings in Black Queer Studies EDITED BY E. Patrick Johnson duke university press Durham & London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Adobe Caslon by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Johnson, E. Patrick, [date] editor. Title: No tea, no shade : new writings in Black queer studies / edited by E. Patrick Johnson. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016022047 (print) lccn 2016023801 (ebook) isbn 9780822362227 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362425 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373711 (e- book) Subjects: lcsh: African American gays. | Gay and lesbian studies. | African Americans in popu lar culture. | Gays in popu lar culture. | Gender identity— Political aspects. | Sex in popu lar culture. Classification: lcc e185.625.n59 2016 (print) | lcc e185.625 (ebook) | ddc 306.76/608996073— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2016022047 Cover art: Philip P. Thomas, Sharing Tea, 2016. © Philip P. Thomas. FOR ALL THE QUEER FOREMOTHERS AND FOREFATHERS This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS foreword Cathy J. Cohen xi acknowl edgments xv introduction E. Patrick Johnson 1 CHAPTER 1. Black/Queer Rhizomatics Train Up a Child in the Way Ze Should Grow . JAFARI S. ALLEN 27 CHAPTER 2. The Whiter the Bread, the Quicker You’re Dead Spectacular Absence and Post-Racialized Blackness in (White) Queer Theory ALISON REED 48 CHAPTER 3. Troubling the Waters Mobilizing a Trans* Analytic KAI M. -

A Socialist Schism

A Socialist Schism: British socialists' reaction to the downfall of Milošević by Andrew Michael William Cragg Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Marsha Siefert Second Reader: Professor Vladimir Petrović CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2017 Copyright notice Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection i Abstract This work charts the contemporary history of the socialist press in Britain, investigating its coverage of world events in the aftermath of the fall of state socialism. In order to do this, two case studies are considered: firstly, the seventy-eight day NATO bombing campaign over the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1999, and secondly, the overthrow of Slobodan Milošević in October of 2000. The British socialist press analysis is focused on the Morning Star, the only English-language socialist daily newspaper in the world, and the multiple publications affiliated to minor British socialist parties such as the Socialist Workers’ Party and the Communist Party of Great Britain (Provisional Central Committee). The thesis outlines a broad history of the British socialist movement and its media, before moving on to consider the case studies in detail. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan)