Claude Mckay's a Long Way from Home

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Pacifist to Anti-Fascist? Sylvia Pankhurst and the Fight Against War and Fascism

FROM PACIFIST TO ANTI-FASCIST? SYLVIA PANKHURST AND THE FIGHT AGAINST WAR AND FASCISM Erika Marie Huckestein A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved By: Susan Pennybacker Emily Burrill Susan Thorne © 2014 Erika Huckestein ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Erika Marie Huckestein: From Pacifist to Anti-Fascist? Sylvia Pankhurst and the Fight Against War and Fascism (Under the direction of Susan Pennybacker) Historians of women’s involvement in the interwar peace movement, and biographers of Sylvia Pankhurst have noted her seemingly contradictory positions in the face of two world wars: she vocally opposed the First World War and supported the Allies from the outbreak of the Second World War. These scholars view Pankhurst’s transition from pacifism to anti-fascism as a reversal or subordination of her earlier pacifism. This thesis argues that Pankhurst’s anti-fascist activism and support for the British war effort should not be viewed as a departure from her earlier suffrage and anti-war activism. The story of Sylvia Pankhurst’s political activism was not one of stubborn commitment to, or rejection of, a static succession of ideas, but one of an active engagement with changing politics, and confrontation with the new ideology of fascism, in a society still struggling to recover from the Great War. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................1 -

Sylvia Pankhurst's Sedition of 1920

“Upheld by Force” Sylvia Pankhurst’s Sedition of 1920 Edward Crouse Undergraduate Thesis Department of History Columbia University April 4, 2018 Seminar Advisor: Elizabeth Blackmar Second Reader: Susan Pedersen With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardor alternated between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that the one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse. – George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1872 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 The End of Edwardian England: Pankhurst’s Political Development ................................. 12 After the War: Pankhurst’s Collisions with Communism and the State .............................. 21 Appealing Sedition: Performativity of Communism and Suffrage ....................................... 33 Prison and Release: Attempted Constructions of Martyrology -

People, Place and Party:: the Social Democratic Federation 1884-1911

Durham E-Theses People, place and party:: the social democratic federation 1884-1911 Young, David Murray How to cite: Young, David Murray (2003) People, place and party:: the social democratic federation 1884-1911, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3081/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk People, Place and Party: the Social Democratic Federation 1884-1911 David Murray Young A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Durham Department of Politics August 2003 CONTENTS page Abstract ii Acknowledgements v Abbreviations vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1- SDF Membership in London 16 Chapter 2 -London -

D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance

‘You are white – yet a part of me’: D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2019 Laura E. Ryan School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................... 3 Declaration ................................................................................................................. 4 Copyright statement ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 1: ‘[G]roping for a way out’: Claude McKay ................................................ 55 Chapter 2: Chaos in Short Fiction: Langston Hughes ............................................ 116 Chapter 3: The Broken Circle: Jean Toomer .......................................................... 171 Chapter 4: ‘Becoming [the superwoman] you are’: Zora Neale Hurston................. 223 Conclusion ............................................................................................................. 267 Bibliography ........................................................................................................... 271 Word Count: 79940 3 -

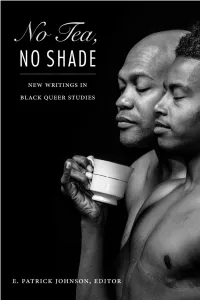

NO TEA, NO SHADE This Page Intentionally Left Blank No Tea, NO SHADE

NO TEA, NO SHADE This page intentionally left blank No Tea, NO SHADE New Writings in Black Queer Studies EDITED BY E. Patrick Johnson duke university press Durham & London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Adobe Caslon by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Johnson, E. Patrick, [date] editor. Title: No tea, no shade : new writings in Black queer studies / edited by E. Patrick Johnson. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016022047 (print) lccn 2016023801 (ebook) isbn 9780822362227 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362425 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373711 (e- book) Subjects: lcsh: African American gays. | Gay and lesbian studies. | African Americans in popu lar culture. | Gays in popu lar culture. | Gender identity— Political aspects. | Sex in popu lar culture. Classification: lcc e185.625.n59 2016 (print) | lcc e185.625 (ebook) | ddc 306.76/608996073— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2016022047 Cover art: Philip P. Thomas, Sharing Tea, 2016. © Philip P. Thomas. FOR ALL THE QUEER FOREMOTHERS AND FOREFATHERS This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS foreword Cathy J. Cohen xi acknowl edgments xv introduction E. Patrick Johnson 1 CHAPTER 1. Black/Queer Rhizomatics Train Up a Child in the Way Ze Should Grow . JAFARI S. ALLEN 27 CHAPTER 2. The Whiter the Bread, the Quicker You’re Dead Spectacular Absence and Post-Racialized Blackness in (White) Queer Theory ALISON REED 48 CHAPTER 3. Troubling the Waters Mobilizing a Trans* Analytic KAI M. -

Levy, Carl. 2017. Malatesta and the War Interventionist Debate 1914-1917: from the ’Red Week’ to the Russian Revolutions

Levy, Carl. 2017. Malatesta and the War Interventionist Debate 1914-1917: from the ’Red Week’ to the Russian Revolutions. In: Matthew S. Adams and Ruth Kinna, eds. Anarchism, 1914-1918: Internationalism, Anti-Militarism and War. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 69-92. ISBN 9781784993412 [Book Section] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/20790/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] 85 3 Malatesta and the war interventionist debate 1914–17: from the ‘Red Week’ to the Russian revolutions Carl Levy This chapter will examine Errico Malatesta’s (1853–1932) position on intervention in the First World War. The background to the debate is the anti-militarist and anti-dynastic uprising which occurred in Italy in June 1914 (La Settimana Rossa) in which Malatesta was a key actor. But with the events of July and August 1914, the alliance of socialists, republicans, syndicalists and anarchists was rent asunder in Italy as elements of this coalition supported intervention on the side of the Entente and the disavowal of Italy’s treaty obligations under the Triple Alliance. Malatesta’s dispute with Kropotkin provides a focus for the anti-interventionist campaigns he fought internationally, in London and in Italy.1 This chapter will conclude by examining Malatesta’s discussions of the unintended outcomes of world war and the challenges and opportunities that the fracturing of the antebellum world posed for the international anarchist movement. -

Suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst in Winchester

SUFFRAGETTE SYLVIA PANKHURST IN WINCHESTER By Ellen Knight1 Before the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified, the Winchester Equal Suffrage League was actively striving to sway legislators and voters to change the law to get votes for women. Nationally, a flood of oratory poured forth in Europe and in America during the grand struggle. Perhaps the most famous suffragette to speak in Winchester was Sylvia Pankhurst. Pankhurst (1882-1960) was the daughter of Emmeline Pankhurst, whom Time named as one of the 100 most Important People of the 20th Century. “She shaped an idea of women for our time; she shook society into a new pattern from which there could be no going back.”2 “We women suffragists have a great mission–the greatest mission the world has ever known. It is to free half the human race, and through that freedom to save the rest,” the elder Pankhurst stated.3 She was joined in her work by her daughters Christabel and Estelle Sylvia. In 1911, Sylvia Pankhurst undertook an American tour. She arrived in New York in January and gave her first talk in the Carnegie Lyceum. Pankhurst found that “the Civic Forum Lecture Bureau had only booked two engagements for me on my arrival.” That quickly changed when the first newspaper reports and interviews were sent out over the wire service. “Telegrams for dates began pouring in, and during my three months’ stay I could satisfy only a small proportion of those who were asking me to speak, though I traveled almost every night, and spoke once, twice, or thrice a day. -

Sylvia Pankhurst Memorial Lecture

Sylvia Pankhurst Memorial Lecture Wortley Hall August 2014 Edited transcript of a talk by The Emily Davison Lodge Philippa Clark: Every year we try and find a speaker who is linked to our movement but who will also broaden our vision because sometimes we can get so focused on our campaigning and specific objectives that we forget about the wider picture. Earlier this year I went to an exhibition at Tate Britain in London of Sylvia Pankhurst’s paintings which made me remember that first and foremost Sylvia’s training was in art and that her original mission had been to be an artist. At the exhibition I read that there had been two dynamic women who had lobbied the Tate in order to get the work on public display. Fortunately, the sisters all thought that it would be a good idea to have them deliver this year’s lecture. So, we’re absolutely delighted that they can tell us in person about Sylvia Pankhurst the artist and why they lobbied for the exhibition. Hester and Olivia are multi-disciplinary artists who collaborate together under the umbrella of something called ‘The Emily Davison Lodge’ - that's Emily Wilding Davison, the suffragette who died trying to pin the flag on the king’s horse. They research and make artworks to re-historicise - which I thought was a good word - the suffragettes, in particular looking at the artists involved in the campaign and the role of militancy. Hester is going to give the talk and Olivia is going to join her at the end to answer any questions. -

THE POLITICAL THOUGHT of the THIRD WORLD LEFT in POST-WAR AMERICA a Dissertation Submitted

LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Washington, DC August 6, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Benjamin Feldman All Rights Reserved ii LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Michael Kazin, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the full intellectual history of the Third World Turn: when theorists and activists in the United States began to look to liberation movements within the colonized and formerly colonized nations of the ‘Third World’ in search of models for political, social, and cultural transformation. I argue that, understood as a critique of the limits of New Deal liberalism rather than just as an offshoot of New Left radicalism, Third Worldism must be placed at the center of the history of the post-war American Left. Rooting the Third World Turn in the work of theorists active in the 1940s, including the economists Paul Sweezy and Paul Baran, the writer Harold Cruse, and the Detroit organizers James and Grace Lee Boggs, my work moves beyond simple binaries of violence vs. non-violence, revolution vs. reform, and utopianism vs. realism, while throwing the political development of groups like the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, and the Third World Women’s Alliance into sharper relief. -

Hunger Strikes and Force Feedings in the British Women's Suffrage

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lehigh University: Lehigh Preserve Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Eckardt Scholars Projects Undergraduate scholarship 5-1-2017 A Woman’s Weapon: Hunger Strikes and Force Feedings in the British Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1903-1917 Gabriele M. Pate Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: https://preserve.lehigh.edu/undergrad-scholarship-eckardt Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pate, Gabriele M., "A Woman’s Weapon: Hunger Strikes and Force Feedings in the British Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1903-1917" (2017). Eckardt Scholars Projects. 20. https://preserve.lehigh.edu/undergrad-scholarship-eckardt/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate scholarship at Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eckardt Scholars Projects by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 A Woman’s Weapon: Hunger Strikes and Force Feedings in the British Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1903-1917 Gaby Pate Senior Honors Thesis Spring 2017 Amardeep Singh 2 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Context for the Founding of the WSPU .......................................................................................... 5 The “Suffrage Army” ..................................................................................................................... -

Introduction 1

Notes Introduction 1 . Similar attempts to link poetry to immediate political occasions have been made by Mark van Wienen in Partisans and Poets: The Political Work of American Poetry in the Great War and by John Marsh’s anthology You Work Tomorrow . See also Nancy Berke’s Women Poets on the Left and John Lowney’s History, Memory, and the Literary Left: Modern American Poetry, 1935–1968 . 2 . Jos é E. Lim ó n discusses the “mixture of poetry and politics” that informed the Chicano movements of the 1960s and 1970s (81). On Vietnam antiwar poetry, see Bibby. There are, of course, countless studies of individual authors that trace their relationships to politics and social movements. I incorporate the relevant studies throughout the chapters. 3 . In analogy to Wallerstein’s model, the literary world has been conceptualized as a largely autonomous cultural space constituted by power struggles between centers, semi-peripheries, and peripheries, most prominently by Franco Moretti and Pascale Casanova (cf. Moretti; Casanova). But since Wallerstein insists that the world-system is concerned with world-economies (global capitalism) and world-empires (nation-states aiming for geopolitical dominance), systems, that is, which cut across cultural and institutional zones, it seems more plausible to posit the modern world-system as the historical horizon of textual production and interpretation. One of the first uses of world-systems analysis for a concep- tualization of postmodernity and postmodern art was Fredric Jameson’s essay “Culture and Finance Capital” ( Cultural Turn 136–61). 4 . Ramazani remains elusive about the extraliterary reference of these poets’ imagination. -

Vol. 40, No. 6, Jul, 1995

NEWS & LETTERS Theory/Practice 'Human Power is its own end'—Marx Vol. 40 - No. 6 JULY 1995 250 Chinatown a Supreme Court opens new racist era J.S. labor by Michelle Landau The U.S. Supreme Court closed out its 1994-95 term in June with a sweeping, retrograde attack on Black jattlefront America, whose effects will be felt for years to come. The Court ruled against the legality of federal mandates for by John Marcotte affirmative action; against efforts to improve the quality It is a long distance from the Midwest farm country of education in segregated inner-city Black schools; and iround Decatur, 111., where Staley, Caterpillar and Fire against initiatives that had succeeded in translating mi stone workers have been on strike or locked out, to New nority group voting rights into voting power. fork City's Chinatown. It is a distance of a thousand All three decisions (by the same 5-4 majority of Jus niles, and of language and culture. tices Rehnquist, Kennedy, Scalia, O'Connor, and Thom But Chinatown is every bit as much a war zone as De- as) represent reversals from the one period in the :atur, and if the Chinese restaurant, garment and con- Court's existence when it responded to the progressive itruction workers could meet the struggling workers thrust of American history, the mid-1950s through the rom Staley and Cat and Firestone, I don't think lan- mid-1970s. All three decisions proclaim a "color-blind so fuage would be a big problem between them. They ciety," and insidiously use the 1950s-60s language of vould speak the same language, the language of freedom equality and civil rights to reduce the meaning of rom slave labor.