Recovering the Queer Subtext of Claude Mckay’S Harlem Shadows

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sexual Subversives Or Lonely Losers? Discourses of Resistance And

SEXUAL SUBVERSIVES OR LONELY LOSERS? DISCOURSES OF RESISTANCE AND CONTAINMENT IN WOMEN’S USE OF MALE HOMOEROTIC MEDIA by Nicole Susann Cormier Bachelor of Arts, Psychology, University of British Columbia: Okanagan, 2007 Master of Arts, Psychology, Ryerson University, 2010 A dissertation presented to Ryerson University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the program of Psychology Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2019 © Nicole Cormier, 2019 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A DISSERTATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract Title: Sexual Subversives or Lonely Losers? Discourses of Resistance and Containment in Women’s Use of Male Homoerotic Media Doctor of Philosophy, 2019 Nicole Cormier, Clinical Psychology, Ryerson University Very little academic work to date has investigated women’s use of male homoerotic media (for notable exceptions, see Marks, 1996; McCutcheon & Bishop, 2015; Neville, 2015; Ramsay, 2017; Salmon & Symons, 2004). The purpose of this dissertation is to examine the potential role of male homoerotic media, including gay pornography, slash fiction, and Yaoi, in facilitating women’s sexual desire, fantasy, and subjectivity – and the ways in which this expansion is circumscribed by dominant discourses regulating women’s gendered and sexual subjectivities. -

Claude Mckay's a Long Way from Home

Through a Black Traveler's Eyes: Claude McKay's A Long Way from Home Tuire Valkeakari Yale University Abstract: This essay analyzes Jamaican-born Claude McKay's discussion of racism(s) and nationalism(~) in his travelogue/autobiography A Long Way from Home ( 1937), in which he chronicles his sojourn in Europe and North Africa and addresses his complex relationship to the United States. Much of McKay's social analysis draws, as this essay establishes, on his observation that racism and nationalism tend to be intertwined and feed 011 each othe1: While describing his travels, McKay presents himselfas a bordercrosser who is "a bad nationalist" and an "internationalist" - a cosmopolitan whose home cannot be defined by any fixed national labels or by nationalist or racialist identity politics. This essay's dialogue with McKay's memoir ultimately reconstructs his difficult and of1-frustrated quest for democracy - the political condition that Ralph Ellison once eloquently equated with "man~· being at home in. the world." Key words: Claude McKay - nationalism - transnationalism - cosmopolitanism - race - racism - travel The way home we seek is that condition of man's being at home in the world, which is called love, and which we tenn democracy. - Ralph Elli son, "Brave Words for a Startling Occasion" I said I was born in the West Indies and lived in the United States and that I was an American, even though I was a British subject, but 1 preferred to think of myself as an internationalist. The chaoL1Sh said he didn't understand what was an internationalist. J laughed and said that an internationalist was a bad nationalist. -

Boys' Love, Cosplay, and Androgynous Idols

Feminist Encounters: A Journal of Critical Studies in Culture and Politics, 3(1-2), 19 ISSN: 2542-4920 Book Review Boys’ Love, Cosplay, and Androgynous Idols: Queer Fan Cultures in Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan Jenny Lin 1* Published: September 10, 2019 Edited By: Maud Lavin, Ling Yang, and Jing Jamie Zhao Publication Date: 2017 Publisher: Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, Queer Asia Series Price: HK $495 (Hong Kong, Macau, Mainland China, and Taiwan) US $60 (Other countries) Number of Pages: 292 pp. hardback. ISBN: 978-988-8390-9 If, like me, you were born before 1990 and are not immersed in online fan cultures, you may never have heard of the acronyms BL and GL that comprise the primary thrust of Boys’ Love, Cosplay, and Androgynous Idols: Queer Fan Cultures in Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan (hereafter Queer Fan Cultures). Fortunately, this captivating anthology’s editors Maud Lavin, Ling Yang, and Jing Jamie Zhao define ‘BL (Boys’ Love, a fan subculture narrating male homoeroticism)’ and ‘GL (Girls’ Love, a fan subculture narrating female homoeroticism)’ (p. xi) at the outset in the Introduction. Lavin, Yang, and Zhao expertly unpack and contextualise these and other terms that may be new to the less enlightened reader – ‘ACG (anime, comics, and games)’ (p. xii); ‘slash/femslash (fan writing practices that explore male/female homoerotic romances)’ (p. xiv); and Chinese slang ‘tongzhi (gay), guaitai (weirdo), ku’er (cool youth)’ (p. xix) – which reappear in fruitful discussions in the following chapters. I recently assigned Queer Fan Cultures in a seminar, and my millennial students, who enthusiastically devoured the book, already knew all about BL, GL, and ACG, as well as related concepts like “cosplay” (costume play, as when people dress like manga and anime characters) and “shipping,” which denotes when fans couple two seemingly heterosexual characters in a same-sex relationship. -

Sylvia Pankhurst's Sedition of 1920

“Upheld by Force” Sylvia Pankhurst’s Sedition of 1920 Edward Crouse Undergraduate Thesis Department of History Columbia University April 4, 2018 Seminar Advisor: Elizabeth Blackmar Second Reader: Susan Pedersen With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardor alternated between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that the one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse. – George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1872 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 The End of Edwardian England: Pankhurst’s Political Development ................................. 12 After the War: Pankhurst’s Collisions with Communism and the State .............................. 21 Appealing Sedition: Performativity of Communism and Suffrage ....................................... 33 Prison and Release: Attempted Constructions of Martyrology -

Film Film Film Film

Annette Michelson’s contribution to art and film criticism over the last three decades has been un- paralleled. This volume honors Michelson’s unique C AMERA OBSCURA, CAMERA LUCIDA ALLEN AND TURVEY [EDS.] LUCIDA CAMERA OBSCURA, AMERA legacy with original essays by some of the many film FILM FILM scholars influenced by her work. Some continue her efforts to develop historical and theoretical frame- CULTURE CULTURE works for understanding modernist art, while others IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION practice her form of interdisciplinary scholarship in relation to avant-garde and modernist film. The intro- duction investigates and evaluates Michelson’s work itself. All in some way pay homage to her extraordi- nary contribution and demonstrate its continued cen- trality to the field of art and film criticism. Richard Allen is Associ- ate Professor of Cinema Studies at New York Uni- versity. Malcolm Turvey teaches Film History at Sarah Lawrence College. They recently collaborated in editing Wittgenstein, Theory and the Arts (Lon- don: Routledge, 2001). CAMERA OBSCURA CAMERA LUCIDA ISBN 90-5356-494-2 Essays in Honor of Annette Michelson EDITED BY RICHARD ALLEN 9 789053 564943 MALCOLM TURVEY Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press WWW.AUP.NL Camera Obscura, Camera Lucida Camera Obscura, Camera Lucida: Essays in Honor of Annette Michelson Edited by Richard Allen and Malcolm Turvey Amsterdam University Press Front cover illustration: 2001: A Space Odyssey. Courtesy of Photofest Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 494 2 (paperback) nur 652 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2003 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permis- sion of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Patricia Highsmith's Queer Disruption: Subverting Gay Tragedy in the 1950S

Patricia Highsmith’s Queer Disruption: Subverting Gay Tragedy in the 1950s By Charlotte Findlay A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Literature Victoria University of Wellington 2019 ii iii Contents Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………..……………..iv Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………v Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..1 1: Rejoicing in Evil: Queer Ambiguity and Amorality in The Talented Mr Ripley …………..…14 2: “Don’t Do That in Public”: Finding Space for Lesbians in The Price of Salt…………………44 Conclusion ...…………………………………………………………………………………….80 Works Cited …………..…………………………………………………………………………83 iv Acknowledgements Thanks to my supervisor, Jane Stafford, for providing always excellent advice, for helping me clarify my ideas by pointing out which bits of my drafts were in fact good, and for making the whole process surprisingly painless. Thanks to Mum and Tony, for keeping me functional for the last few months (I am sure all the salad improved my writing immensely.) And last but not least, thanks to the ladies of 804 for the support, gossip, pad thai, and niche literary humour I doubt anybody else would appreciate. I hope your year has been as good as mine. v Abstract Published in a time when tragedy was pervasive in gay literature, Patricia Highsmith’s 1952 novel The Price of Salt, published later as Carol, was the first lesbian novel with a happy ending. It was unusual for depicting lesbians as sympathetic, ordinary women, whose sexuality did not consign them to a life of misery. The novel criticises how 1950s American society worked to suppress lesbianism and women’s agency. It also refuses to let that suppression succeed by giving its lesbian couple a future together. -

Sober and Alone: a Phenomenological Exploration of the Loneliness Experienced by Recovering Alcoholics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Liberty University Digital Commons SOBER AND ALONE: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL EXPLORATION OF THE LONELINESS EXPERIENCED BY RECOVERING ALCOHOLICS by Timothy J. Evans Liberty University A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Liberty University February 2010 © Timothy J. Evans, February, 2010 All Rights Reserved ii SOBER AND ALONE: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL EXPLORATION OF THE LONELINESS EXPERIENCED BY RECOVERING ALCOHOLICS A Dissertation Proposal Submitted to the Faculty of Liberty University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy by Timothy J. Evans Liberty University, Lynchburg, Virginia February, 2010 Dissertation Committee Approval: _________________________________________ FRED MILACCI, D.Ed., Chair date _________________________________________ KENNETH REEVES, Ed.D., Reader date _________________________________________ ROBERT LEHMAN, Ph.D., Reader date _________________________________________ LISA SOSIN. Ph.D., Reader date iii ABSTRACT SOBER AND ALONE: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL EXPLORATION OF THE LONELINESS EXPERIENCED BY RECOVERING ALCOHOLICS By Timothy J. Evans Center for Counseling and Family Studies Liberty University, Lynchburg, Virginia Doctor of Philosophy in Counseling This phenomenological inquiry investigated the loneliness experienced by recovering alcoholics. Select participants responded to open-ended interview questions pertaining to their experience of loneliness as well as its impact on their lives. Moreover, participants were asked to indentify what factor or factors may have contributed to the onset or persistence of their loneliness. Phenomenological analysis of the data revealed that loneliness, as experienced by recovering alcoholics, is a recursive experience that is co-morbid with a number of debilitating affects. Therefore, the loneliness that was experienced during recovery represented just one part of a combination of painful affective experiences. -

Taylor Boulware a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The

Fascination/Frustration: Slash Fandom, Genre, and Queer Uptake Taylor Boulware A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Thomas Foster, Chair Anis Bawarshi Katherine Cummings Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of English Fascination/Frustration: Slash Fandom, Genre, and Queer Uptake by Taylor Boulware The University of Washington, 2017 Under the Supervision of Professor Dr. Thomas Foster ABSTRACT This dissertation examines contemporary television slash fandom, in which fans write and circulate creative texts that dramatize non-canonical queer relationships between canonically heterosexual male characters. These texts contribute to the creation of global networks of affective and social relations, critique the specific corporate media texts from which they emerge, and undermine homophobic ideologies that prevent authentic queer representation in mainstream media. Intervening in dominant scholarly and popular arguments about slash fans, I maintain a rigorous distinction between the act of reading homoerotic subtexts in TV shows and writing fiction that makes that homoeroticism explicit, in every sense of the word.This emphasis on writing and the circulation of responsive, recursive texts can best be understood, I argue, through the framework of Rhetorical Genre Studies, which theorizes genres and the ways in which they are deployed, modified, and circulated as ideological and social action. I nuance the RGS concept of uptake, which names the generic dimensions of utterance and response, and define my concept of queer uptake, in which writers respond to a text in ways that refuse its generic boundaries and status, motivated by an ideological resistance to both genre and sexual normativity. -

D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance

‘You are white – yet a part of me’: D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2019 Laura E. Ryan School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................... 3 Declaration ................................................................................................................. 4 Copyright statement ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 1: ‘[G]roping for a way out’: Claude McKay ................................................ 55 Chapter 2: Chaos in Short Fiction: Langston Hughes ............................................ 116 Chapter 3: The Broken Circle: Jean Toomer .......................................................... 171 Chapter 4: ‘Becoming [the superwoman] you are’: Zora Neale Hurston................. 223 Conclusion ............................................................................................................. 267 Bibliography ........................................................................................................... 271 Word Count: 79940 3 -

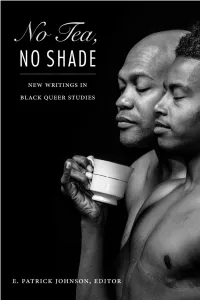

NO TEA, NO SHADE This Page Intentionally Left Blank No Tea, NO SHADE

NO TEA, NO SHADE This page intentionally left blank No Tea, NO SHADE New Writings in Black Queer Studies EDITED BY E. Patrick Johnson duke university press Durham & London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Adobe Caslon by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Johnson, E. Patrick, [date] editor. Title: No tea, no shade : new writings in Black queer studies / edited by E. Patrick Johnson. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016022047 (print) lccn 2016023801 (ebook) isbn 9780822362227 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362425 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373711 (e- book) Subjects: lcsh: African American gays. | Gay and lesbian studies. | African Americans in popu lar culture. | Gays in popu lar culture. | Gender identity— Political aspects. | Sex in popu lar culture. Classification: lcc e185.625.n59 2016 (print) | lcc e185.625 (ebook) | ddc 306.76/608996073— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2016022047 Cover art: Philip P. Thomas, Sharing Tea, 2016. © Philip P. Thomas. FOR ALL THE QUEER FOREMOTHERS AND FOREFATHERS This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS foreword Cathy J. Cohen xi acknowl edgments xv introduction E. Patrick Johnson 1 CHAPTER 1. Black/Queer Rhizomatics Train Up a Child in the Way Ze Should Grow . JAFARI S. ALLEN 27 CHAPTER 2. The Whiter the Bread, the Quicker You’re Dead Spectacular Absence and Post-Racialized Blackness in (White) Queer Theory ALISON REED 48 CHAPTER 3. Troubling the Waters Mobilizing a Trans* Analytic KAI M. -

Max Reinhardt and William Dieterle's a Midsummer Night's Dream And

Guy Patricia, Anthony. "Max Reinhardt and William Dieterle’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and the queer problematics of gender, sodomy, marriage and masculinity." Queering the Shakespeare Film: Gender Trouble, Gay Spectatorship and Male Homoeroticism. London: Bloomsbury Arden Shakespeare, 2017. 1–40. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 27 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474237062.ch-001>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 27 September 2021, 03:39 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Guy Patricia 2017. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 1 Max Reinhardt and William Dieterle ’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and the queer problematics of gender, sodomy, marriage and masculinity I Before helming Warner Brothers’ 1935 film ofA Midsummer Night’s Dream, co-director Max Reinhardt had staged the play many times in live-theatre venues in Germany and Austria and on the east and west coasts of America.1 Thus, even though cinema provided a new medium in which to work, he was no neophyte to Shakespeare in performance. The movie Reinhardt and his colleague William Dieterle made offers audiences as much spectacle as Shakespearean comedy: sumptuous sets and intriguing special effects; remarkably 9781474237031_txt_print.indd 1 29/07/2016 14:51 2 QUEERING THE SHAKESPEARE FILM innovative cinematography for the time of its making and a mise-en-scène that reward careful attention; a range of -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind.