Introduction 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia Douglas Johnson and Eulalie Spence As Figures Who Fostered Community in the Midst of Debate

Art versus Propaganda?: Georgia Douglas Johnson and Eulalie Spence as Figures who Fostered Community in the Midst of Debate Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Caroline Roberta Hill, B.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2019 Thesis Committee: Jennifer Schlueter, Adviser Beth Kattelman Copyright by Caroline Roberta Hill 2019 Abstract The Harlem Renaissance and New Negro Movement is a well-documented period in which artistic output by the black community in Harlem, New York, and beyond, surged. On the heels of Reconstruction, a generation of black artists and intellectuals—often the first in their families born after the thirteenth amendment—spearheaded the movement. Using art as a means by which to comprehend and to reclaim aspects of their identity which had been stolen during the Middle Passage, these artists were also living in a time marked by the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and segregation. It stands to reason, then, that the work that has survived from this period is often rife with political and personal motivations. Male figureheads of the movement are often remembered for their divisive debate as to whether or not black art should be politically charged. The public debates between men like W. E. B. Du Bois and Alain Locke often overshadow the actual artistic outputs, many of which are relegated to relative obscurity. Black female artists in particular are overshadowed by their male peers despite their significant interventions. Two pioneers of this period, Georgia Douglas Johnson (1880-1966) and Eulalie Spence (1894-1981), will be the subject of my thesis. -

Claude Mckay's a Long Way from Home

Through a Black Traveler's Eyes: Claude McKay's A Long Way from Home Tuire Valkeakari Yale University Abstract: This essay analyzes Jamaican-born Claude McKay's discussion of racism(s) and nationalism(~) in his travelogue/autobiography A Long Way from Home ( 1937), in which he chronicles his sojourn in Europe and North Africa and addresses his complex relationship to the United States. Much of McKay's social analysis draws, as this essay establishes, on his observation that racism and nationalism tend to be intertwined and feed 011 each othe1: While describing his travels, McKay presents himselfas a bordercrosser who is "a bad nationalist" and an "internationalist" - a cosmopolitan whose home cannot be defined by any fixed national labels or by nationalist or racialist identity politics. This essay's dialogue with McKay's memoir ultimately reconstructs his difficult and of1-frustrated quest for democracy - the political condition that Ralph Ellison once eloquently equated with "man~· being at home in. the world." Key words: Claude McKay - nationalism - transnationalism - cosmopolitanism - race - racism - travel The way home we seek is that condition of man's being at home in the world, which is called love, and which we tenn democracy. - Ralph Elli son, "Brave Words for a Startling Occasion" I said I was born in the West Indies and lived in the United States and that I was an American, even though I was a British subject, but 1 preferred to think of myself as an internationalist. The chaoL1Sh said he didn't understand what was an internationalist. J laughed and said that an internationalist was a bad nationalist. -

HARLEM in SHAKESPEARE and SHAKESPEARE in HARLEM: the SONNETS of CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, and GWENDOLYN BROOKS David J

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2015 HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS David J. Leitner Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Leitner, David J., "HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS" (2015). Dissertations. Paper 1012. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS by David Leitner B.A., University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana, 1999 M.A., Southern Illinois University Carbondale, 2005 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Department of English in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2015 DISSERTATION APPROVAL HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS By David Leitner A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Approved by: Edward Brunner, Chair Robert Fox Mary Ellen Lamb Novotny Lawrence Ryan Netzley Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April 10, 2015 AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF DAVID LEITNER, for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in ENGLISH, presented on April 10, 2015, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. -

Sylvia Pankhurst's Sedition of 1920

“Upheld by Force” Sylvia Pankhurst’s Sedition of 1920 Edward Crouse Undergraduate Thesis Department of History Columbia University April 4, 2018 Seminar Advisor: Elizabeth Blackmar Second Reader: Susan Pedersen With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardor alternated between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that the one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse. – George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1872 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 The End of Edwardian England: Pankhurst’s Political Development ................................. 12 After the War: Pankhurst’s Collisions with Communism and the State .............................. 21 Appealing Sedition: Performativity of Communism and Suffrage ....................................... 33 Prison and Release: Attempted Constructions of Martyrology -

D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance

‘You are white – yet a part of me’: D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2019 Laura E. Ryan School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................... 3 Declaration ................................................................................................................. 4 Copyright statement ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 1: ‘[G]roping for a way out’: Claude McKay ................................................ 55 Chapter 2: Chaos in Short Fiction: Langston Hughes ............................................ 116 Chapter 3: The Broken Circle: Jean Toomer .......................................................... 171 Chapter 4: ‘Becoming [the superwoman] you are’: Zora Neale Hurston................. 223 Conclusion ............................................................................................................. 267 Bibliography ........................................................................................................... 271 Word Count: 79940 3 -

The Harlem Renaissance: a Handbook

.1,::! THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY ELLA 0. WILLIAMS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA JULY 1987 3 ABSTRACT HUMANITIES WILLIAMS, ELLA 0. M.A. NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, 1957 THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK Advisor: Professor Richard A. Long Dissertation dated July, 1987 The object of this study is to help instructors articulate and communicate the value of the arts created during the Harlem Renaissance. It focuses on earlier events such as W. E. B. Du Bois’ editorship of The Crisis and some follow-up of major discussions beyond the period. The handbook also investigates and compiles a large segment of scholarship devoted to the historical and cultural activities of the Harlem Renaissance (1910—1940). The study discusses the “New Negro” and the use of the term. The men who lived and wrote during the era identified themselves as intellectuals and called the rapid growth of literary talent the “Harlem Renaissance.” Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925) and James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan (1930) documented the activities of the intellectuals as they lived through the era and as they themselves were developing the history of Afro-American culture. Theatre, music and drama flourished, but in the fields of prose and poetry names such as Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Zora Neale Hurston typify the Harlem Renaissance movement. (C) 1987 Ella 0. Williams All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special recognition must be given to several individuals whose assistance was invaluable to the presentation of this study. -

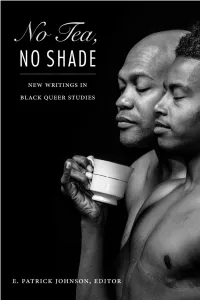

NO TEA, NO SHADE This Page Intentionally Left Blank No Tea, NO SHADE

NO TEA, NO SHADE This page intentionally left blank No Tea, NO SHADE New Writings in Black Queer Studies EDITED BY E. Patrick Johnson duke university press Durham & London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Adobe Caslon by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Johnson, E. Patrick, [date] editor. Title: No tea, no shade : new writings in Black queer studies / edited by E. Patrick Johnson. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016022047 (print) lccn 2016023801 (ebook) isbn 9780822362227 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362425 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373711 (e- book) Subjects: lcsh: African American gays. | Gay and lesbian studies. | African Americans in popu lar culture. | Gays in popu lar culture. | Gender identity— Political aspects. | Sex in popu lar culture. Classification: lcc e185.625.n59 2016 (print) | lcc e185.625 (ebook) | ddc 306.76/608996073— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2016022047 Cover art: Philip P. Thomas, Sharing Tea, 2016. © Philip P. Thomas. FOR ALL THE QUEER FOREMOTHERS AND FOREFATHERS This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS foreword Cathy J. Cohen xi acknowl edgments xv introduction E. Patrick Johnson 1 CHAPTER 1. Black/Queer Rhizomatics Train Up a Child in the Way Ze Should Grow . JAFARI S. ALLEN 27 CHAPTER 2. The Whiter the Bread, the Quicker You’re Dead Spectacular Absence and Post-Racialized Blackness in (White) Queer Theory ALISON REED 48 CHAPTER 3. Troubling the Waters Mobilizing a Trans* Analytic KAI M. -

Carnival, Convents, and the Cult of St. Rocque: Cultural Subterfuge in the Work of Alice Dunbar-Nelson

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English Summer 8-9-2012 Carnival, Convents, and the Cult of St. Rocque: Cultural Subterfuge in the Work of Alice Dunbar-Nelson Sibongile B. Lynch Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Recommended Citation Lynch, Sibongile B., "Carnival, Convents, and the Cult of St. Rocque: Cultural Subterfuge in the Work of Alice Dunbar-Nelson." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/136 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CARNIVAL, CONVENTS, AND THE CULT OF ST. ROCQUE: CULTURAL SUBTERFUGE IN THE WORK OF ALICE DUNBAR-NELSON by SIBONGILE B. N. LYNCH Under the Direction of Elizabeth J. West ABSTRACT In the work of Alice Dunbar-Nelson the city and culture of 19th century New Orleans fig- ures prominently, and is a major character affecting the lives of her protagonists. While race, class, and gender are among the focuses of many scholars the eccentricity and cultural history of the most exotic American city, and its impact on Dunbar-Nelson’s writing is unmistakable. This essay will discuss how the diverse cultural environment of New Orleans in the 19th century allowed Alice Dunbar Nelson to create narratives which allowed her short stories to speak to the shifting identities of women and the social uncertainty of African Americans in the Jim Crow south. -

The Black Women's Contribution to the Harlem Renaissance 1919-1940

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research University Abd El Hamid Ibn Badis Faculty of Foreign Languages English Language The Black Women's Contribution to the Harlem Renaissance 1919-1940 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master in Literature and Interdisciplinary Approaches Presented By: Rahma ZIAT Board of Examiners: Chairperson: Dr. Belghoul Hadjer Supervisor: Djaafri Yasmina Examiner: Dr. Ghaermaoui Amel Academic Year: 2019-2020 i Dedication At the outset, I have to thank “Allah” who guided and gave me the patience and capacity for having conducted this research. I would like to dedicate this dissertation to my family and my friends. A very special feeling of gratitude to my loving father, and mother whose words of encouragement and push for tenacity ring in my ears. To my grand-mother, for her eternal love. Also, my sisters and brother, Khadidja, Bouchra and Ahmed who inspired me to be strong despite many obstacles in life. To a special person, my Moroccan friend Sami, whom I will always appreciate his support and his constant inspiration. To my best friend Fethia who was always there for me with her overwhelming love. Acknowledgments Foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Mrs.Djaafri for her continuous support in my research, for her patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and immense knowledge. Her guidance helped me in all the time of research and writing of this thesis. I could not have imagined having a better advisor and mentor for dissertation. I would like to deeply thank Mr. -

Flyer Reju Nov-10

97 rue Henri Barbusse 92110 CLICHY FRANCE [email protected] www.rejuvenationrecords.com Voici une petite liste de distrib sans prétention juste pour faire plaisir à tes oreilles, on espère que tu trouveras des choses intéressantes… Notre but n'est pas de faire du profit, mais juste de rentrer dans nos frais. Les disques sont neufs (ou alors c'est précisé), et nous garantissons tout ce que nous vendons. READ THIS BEFORE ANY ORDER ! 1 - Because of our very limited stocks, please send an e-mail to Agnès before any order : agnes(at)rejuvenationrecords.com 2 - All Prices are in EURO. 3 - Shipping is not included, notify us where you live and we will give it to you. 4 - You can pay with well hidden cash (in EURO, please, and at your own risk). 5 - You can pay by paypal to rejuvenation(at)wanadoo.fr. Please add 5% for paypal fees. 6 - You can pay by IMO, just ask us ! 7 - If payment is not received within two weeks of e-mailing us to reserve an order, the order is cancelled. 8 - Now if you're agree with previous lines, we can being very good friends. To have an idea of what can be the shipping costs look at the board below. Thank you ! T'es super nul en anglais (pire que nous ?), ok c'est pas grave : A LIRE AVANT TOUTE COMMANDE ! 1 - En raison de nos quantités super limitées merci de contacter Agnès avant toute commande : agnes(at)rejuvenationrecords.com 2 - Tous les prix sont en EURO. 3 - Le port n'est pas compris, donc dis nous où tu habites et on te donnera le port. -

Corbould - Issue Four - Colloquy

Corbould - Issue four - Colloquy "What is Modernism to me?" Individual Selves and Collective Identities in African-American Women's Writing, 1920-1935 Claire Corbould The brick wall that is any attempt to define "modernism" sent me running to the Oxford Companion to English Literature . Here I found that in an effort to break thoroughly with the past, modernist writing is characterised in part by an awareness of the unconscious and an interest in the presentation of personality. At the very least, it can be assumed that popular conceptions of modernist writing concern the "inner" self, its relationship or interaction with the "outer" self, and, more generally, the presentation of the individual [1] . Moreover, popular definitions of modernism ñin the USA as well as in Britain ñ continue to prioritise the avant-garde and experimentation with form. Perhaps the most famous examples are Molly Bloom and Alice B. Toklas. Bloom's "stream-of-consciousness" account which concludes James Joyce's Ulysses is taken as emblematic of modernist expression, and is cited as such by the Oxford Companion [2] . It is easy to see how, within such paradigms, the cultural production of the Harlem Renaissance has been neglected in the historical consideration of modernism. Nathan Huggins, in his important 1971 work, Harlem Renaissance, exemplifies this attitude in his discussion of the poetry of the period. Countee Cullen and Claude McKay, he argues, were hamstrung by their adherence to forms such as the sonnet. Such formalism, he argues, reflects a basic conservatism. Cullen, was, a "perfect example of a twentieth- century poet marching to a nineteenth-century drummer .. -

African-American Writers

AFRICAN-AMERICAN WRITERS Philip Bader Note on Photos Many of the illustrations and photographs used in this book are old, historical images. The quality of the prints is not always up to current standards, as in some cases the originals are from old or poor-quality negatives or are damaged. The content of the illustrations, however, made their inclusion important despite problems in reproduction. African-American Writers Copyright © 2004 by Philip Bader All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bader, Philip, 1969– African-American writers / Philip Bader. p. cm.—(A to Z of African Americans) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and indexes. ISBN 0-8160-4860-6 (acid-free paper) 1. American literature—African American authors—Bio-bibliography—Dictionaries. 2. African American authors—Biography—Dictionaries. 3. African Americans in literature—Dictionaries. 4. Authors, American—Biography—Dictionaries. I. Title. II. Series. PS153.N5B214 2004 810.9’96073’003—dc21 2003008699 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Joan M.