Revisionism: the Politics of the CPGB Past & Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marxism Today: the Forgotten Visionaries Whose Ideas Could Save Labour John Harris Tuesday, 29 September 2015

Marxism Today: the forgotten visionaries whose ideas could save Labour John Harris Tuesday, 29 September 2015 The best guide to politics in 2015 is a magazine that published its final issue more than two decades ago A selection of Marxism Today’s greatest covers. Composite: Amiel Melburn Trust In May 1988, a group of around 20 writers and academics spent a weekend at Wortley Hall, a country house north of Sheffield, loudly debating British politics and the state of the world. All drawn from the political left, by that point they were long used to defeat, chiefly at the hands of Margaret Thatcher. Now, they were set on figuring out not just how to reverse the political tide, but something much more ambitious: in essence, how to leave the 20th century. Over the previous decade, some of these people had shone light on why Britain had moved so far to the right, and why the left had become so weak. But as one of them later put it, they now wanted to focus on “how society was changing, what globalisation was about – where things were moving in a much, much deeper sense”. The conversations were not always easy; there were raised voices, and sometimes awkward silences. Everything was taped, and voluminous notes were taken. A couple of months on, one of the organisers wrote that proceedings had been “part coherent, part incoherent, exciting and frustrating in just about equal measure”. What emerged from the debates and discussions was an array of amazingly prescient insights, published in a visionary magazine called Marxism Today. -

Labor History Subject Catalog

Labor History Catalog of Microform (Research Collections, Serials, and Dissertations) www.proquest.com/en-US/catalogs/collections/rc-search.shtml [email protected] 800.521.0600 ext. 2793 or 734.761.4700 ext. 2793 USC009-03 updated May 2010 Table of Contents About This Catalog ............................................................................................... 2 The Advantages of Microform ........................................................................... 3 Research Collections............................................................................................. 4 African Labor History .......................................................................................................................................5 Asian Labor History ..........................................................................................................................................6 British Labor History ........................................................................................................................................8 Canadian Labor History ................................................................................................................................. 20 Caribbean Labor History ................................................................................................................................ 22 French Labor History ...................................................................................................................................... 24 Globalization -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sussex Research Online A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Children of the Red Flag Growing Up in a Communist Family During the Cold War: A Comparative Analysis of the British and Dutch Communist Movement Elke Marloes Weesjes Dphil University of Sussex September 2010 1 Statement I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature:……………………………………… 2 Abstract This thesis assesses the extent of social isolation experienced by Dutch and British ‘children of the red flag’, i.e. people who grew up in communist families during the Cold War. This study is a comparative research and focuses on the political and non-political aspects of the communist movement. By collating the existing body of biographical research and prosopographical literature with oral testimonies this thesis sets out to build a balanced picture of the British and Dutch communist movement. -

Welsh Communist Party) Papers (GB 0210 PEARCE)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Bert Pearce (Welsh Communist Party) Papers (GB 0210 PEARCE) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 05, 2017 Printed: May 05, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH This description follows NLW guidelines based on ISAD(G) Second Edition; AACR2; and LCSH. https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/bert-pearce-welsh-communist-party- papers-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/bert-pearce-welsh-communist-party-papers-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Bert Pearce (Welsh Communist Party) Papers Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 5 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................ -

Towards a Unified Theory Analysing Workplace Ideologies: Marxism And

Marxism and Racial Oppression: Towards a Unified Theory Charles Post (City University of New York) Half a century ago, the revival of the womens movementsecond wave feminismforced the revolutionary left and Marxist theory to revisit the Womens Question. As historical materialists in the 1960s and 1970s grappled with the relationship between capitalism, class and gender, two fundamental positions emerged. The dominant response was dual systems theory. Beginning with the historically correct observation that male domination predates the emergence of the capitalist mode of production, these theorists argued that contemporary gender oppression could only be comprehended as the result of the interaction of two separate systemsa patriarchal system of gender domination and the capitalist mode of production. The alternative approach emerged from the debates on domestic labor and the predominantly privatized character of the social reproduction of labor-power under capitalism. In 1979, Lise Vogel synthesized an alternative unitary approach that rooted gender oppression in the tensions between the increasingly socialized character of (most) commodity production and the essentially privatized character of the social reproduction of labor-power. Today, dual-systems theory has morphed into intersectionality where distinct systems of class, gender, sexuality and race interact to shape oppression, exploitation and identity. This paper attempts to begin the construction of an outline of a unified theory of race and capitalism. The paper begins by critically examining two Marxian approaches. On one side are those like Ellen Meiksins Wood who argued that capitalism is essentially color-blind and can reproduce itself without racial or gender oppression. On the other are those like David Roediger and Elizabeth Esch who argue that only an intersectional analysis can allow historical materialists to grasp the relationship of capitalism and racial oppression. -

REVIEWS (Composite) REVIEWS (Composite).Qxd 5/16/2019 12:44 PM Page 98

19REVIEWS (Composite)_REVIEWS (Composite).qxd 5/16/2019 12:44 PM Page 98 98 Reviews Eric Richard J. Evans, Eric Hobsbawm: A Life in History, Little, Brown, 2019, 798 pages, hardback ISBN9781408707418, £35 Hobsbawm always insisted on ‘Eric’, so Eric he will be here. This is something of a departure for Evans, best known for his many books on Germany and Nazism, also for lethal testimony in the David IrvingDeborah Lipstadt trial. My uncorrected proof copy lacks both illustrations and bibliography. The latter can be excavated from the 81 pages of endnotes, meticulously sourcedocumented plus extra information supplementary to the main narrative. The excellent 36page Index (eight devoted to Eric) comports a list of his books. Long life (95 years), so long book. Much value accrues from use of Eric’s unpublished Diaries (mainly in German) and his multigeneric fugitive pieces. Complementary is Eric’s memoir, Interesting Times, dubbed (page ix) by Stefan Collini as ‘that interesting hybrid, an impersonal autobiography’. This doorstopper is friendly (the two were well acquainted) but not a hagiography; Eric gets his fair share of flak, personal and political. Book ended by provocative Preface and Conclusion, the ten, chronologically arranged chapters come with nifty titles that shape a minibiography: The English Boy; Ugly as Sin, but a Mind; A Freshman Who Knows About Everything; A Leftwing Intellectual in the English Army; Outsider in the Movement; A Dangerous Character; Paperback Writer (shared with the Beatles – Eric, though, detested all pop music); Intellectual Guru; Jeremiah; National Treasure. Eric had a knack for chronological coincidences. -

Zaidman Papers

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 118 Title: Zaidman Papers Scope: Printed and manuscript documents assembled by Lazar Zaidman relating to the Anti-Fascist movement in London and to the Communist Party of Great Britain during the period 1930s to 1950s, and to Jewish affairs during this period, including the origins of the state of Israel. Dates: 1911 - 1961 (mainly 1930s to 1950s) Level: Fonds Extent: 49 files plus 249 pamphlets Name of creator: Lazar Zaidman Administrative / biographical history: The collection consists of printed ephemera and manuscript documents relating to the Anti-Fascist movement in London and to the Communist Party of Great Britain during the period 1930s to 1950s. There is also material on Jewish affairs during this period, including the origins of the state of Israel. A collection of pamphlets is included. Lazar Zaidman (1903-1963) was a leading London Communist during the period of the 1930s to the 1950s. He was born in Jubilee Street in the East End to a Jewish family in 1903, but returned with his family to Rumania in 1912 because of his mother’s health. As this did not improve, the family were due to return to England in 1914 but were prevented from doing so by the outbreak of World War One. In Rumania he became involved in trade unionism and therefore politics at a time when even mild liberalism was an offence, and spent 3 years in prison where he was tortured and beaten, losing the hearing in his left ear and the sight in his left eye as a result. -

Letters July 1986 Marxism Today 39

Letters July 1986 Marxism Today 39 UNPOPULAR PERCEPTIONS away from an 'edge of darkness' are UNEQUAL AID wasn't bad enough, they also tend to It was alarming to witness Richard now part of national and spiritual It's about time we had a socialist hide the fact that Third World people Kinsey's reliance (MT May) on aspirations. With some of these perspective on development (Aid themselves are organising to fight people's experiences and perceptions aspirations being represented by Crusade, MT June). But what is a famine. The 'Images of Africa' entry in of crime and policing (as if these were Britain's ancient monuments, there is socialist perspective? Five years' the Women Alive programme reads: never contradictory), and on greater a struggle going on forthe meaning experience in the development 'Presenting positive images (in police effectiveness (as if this was of 'national heritage'. The Left would movement has led us to believe that contrast to Live Aid and the Sunday unproblematic), as key components do well to consider this. what we need is a change in the supplements) is a part of fighting the in a socialist strategy in this area. Mike Welter, Penge concept of charity and aid. racism and imperialism facing You would not imagine reading GOLLAN BIOGRAPHY Although some charities produce Afro-Caribbean and African women'. this article, nor reading the survey I am collecting material with a view to some (very good) educational A socialist perspective, if it is to be reports themselves, that findings writing a biography of John Gollan, material, their fundraising techniques anti-racist, must challenge this based sole/y on questionnaire-based who was general secretary of the are more often than not racist. -

The Twentieth Congress and the British Communist Party*

THE TWENTIETH CONGRESS AND THE BRITISH COMMUNIST PARTY* by John Saville No one in Western Europe could have foreseen the extraordinary events of 1956 in Eastern ~uro~e.'The year opened with the general belief that the cautious de-stalinisation which had begun with Stalin's death in the Spring of 1953 would continue. In Yugoslavia-a useful yardstick by which to measure changes in Soviet policy-a trade agreement had been signed in October 1954, and about the same time Tito's speeches began to be factually reported. ,During 195 5 there was a continued improvement in diplomatic and political relations, with a visit of the Soviet leaders to Belgrade in May-in the course of which Khrushchev put all the blame for the bitter dispute between the two countries upon Beria-an accusation that was soon to be extended to cover most of the crimes of the later Stalin years. Inside the Soviet Union the principle of collective leadership was increasingly re-affirmed, and the cult of the individual increasingly denounced. Stalin was not yet, however, named as at least part villain of the piece. Indeed a Moscow despatch from Alexander Werth of the New Statesman (28th January 1956) suggested a certain rehabilitation of Stalin's reputation in the closing months of 1955. However, the 20th Congress was soon to define 'the Stalin question' in very certain terms. The 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union met towards the end of February 1956. All the world's communist parties sent their leading comrades as fraternal delegates; from Britain these were Harry Pollitt, general secretary; George Matthews, assistant general secretary; and R. -

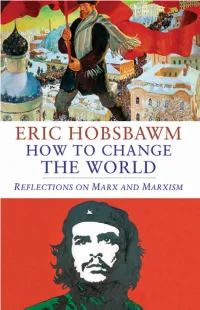

How to Change the World Also by Eric Hobsbawm

How to Change the World Also by Eric Hobsbawm The Age of Revolution 1789–1848 The Age of Capital 1848–1875 The Age of Empire 1875–1914 The Age of Extremes 1914–1991 Labouring Men Industry and Empire Bandits Revolutionaries Worlds of Labour Nations and Nationalism Since 1780 On History Uncommon People The New Century Globalisation, Democracy and Terrorism Interesting Times How to Change the World Reflections on Marx and Marxism Eric Hobsbawm New Haven & London To the memory of George Lichtheim This collection first published 2011 in the United States by Yale University Press and in Great Britain by Little, Brown. Copyright © 2011 by Eric Hobsbawm. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] (U.S. office) or [email protected] (U.K. office). Typeset in Baskerville by M Rules. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Control Number: 2011927314 ISBN 978-0-300-17616-2 (hardcover : alk. paper) A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Foreword vii PART I: MARX AND ENGELS 1 Marx Today 3 2 Marx, -

Alex Callinicos the Politics of Marxism Today

Alex Callinicos The politics of Marxism Today (Summer 1985) From International Socialism 2 : 29, Summer 1985. Transcribed by Christian Høgsbjerg. Marked up by Einde O’ Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On- Line (ETOL). Marxism Today, the theoretical and discussion journal of the Communist Party of Great Britain, has been transformed since 1977 from a rather dull monthly of interest only, if at all, to CP members to a lively, attractively produced and controversial magazine widely read on the left. The change has something to do with style – the replacement of old Party workhorse James Klugmann with the present editor, Martin Jacques. Fundamentally, however, it reflects the emergence of a new theoretical and political current, the Eurocommunist wing of the party, which has not only played a major role in precipitating the present split in the CP, but seeks to bring about a more general re-alignment of the left. Ralph Miliband aptly described the politics of this tendency recently when he called it the ‘new revisionism’, marking ‘a very pronounced retreat from some socialist positions.’ [1] The essence of this retreat was correctly summarized by some supporters of the Morning Star wing of the Communist Party, the authors of the widely discussed pamphlet Class Politics: ‘there has been a shift away from, even an abandonment of, the central role of class and class conflict in the analysis and formation of political strategy.’ [2] There are three reasons for discussing the politics of the new revisionism in this journal. The first is that theirs are not simply ideas formulated by a few left-wing academics with no effect on broader movements and struggles. -

Paul Flewers and John Mcilroy (Eds), 1956: John Saville, E.P. Thompson & The

University of Huddersfield Repository Laybourn, Keith Book review: 1956: John Saville, E.P. Thompson & The Reasoner Original Citation Laybourn, Keith (2017) Book review: 1956: John Saville, E.P. Thompson & The Reasoner. Labor History, 58 (4). pp. 579-581. ISSN 0023-656X This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/32484/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Paul Flewers and John McIlroy (eds), 1956: John Saville, E.P. Thompson & The Reasoner , London, Merlin Press, 2016, ISBN 978 0 85036 726 3 , £20 1956 was a dramatic year in both the history of world and British communism for it saw Krushchev ‘Secret Speech’ reveal the iniquities of Stalin, the Soviet invasion of Hungary, and deep divisions develop within the Communist Party of Great Britain over the restrictive bonds of democratic centralism which stifled open debate within the party.