Marxism Today: the Forgotten Visionaries Whose Ideas Could Save Labour John Harris Tuesday, 29 September 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POLIM0006: East Asia and Global Development Unit Guide 2017/18 Teaching Block 1

POLIM0006: East Asia and Global Development Unit Guide 2017/18 Teaching Block 1 Unit Owner: Professor Jeffrey Henderson Level: M Credit points: 20 Phone (0117) 928 8380 Prerequisites: None Email [email protected] Office 1.1, 10 Priory Road http://www.bris.ac.uk/ceas/members/core/henderson.shtml Make sure you check your Bristol email account regularly throughout the course as important information will be communicated to you. Any emails sent to your Bristol address are assumed to have been read. If you wish for emails to be forwarded to an alternative address then please go to https://wwws.cse.bris.ac.uk/cgi-bin/redirect-mailname-external Unit description East Asia and Global Development (EAGD) seeks to survey the dynamic relations between the more prominent East Asian countries and the global political economy as these have evolved over the last half century or so. The tenor of the unit, therefore, is necessarily theoretical and historical-comparative. Though the key dynamics that now constitute and transform our world are increasingly global in origin, they continue to impact and combine with processes and events that are nationally specific. Into the economic, political and social maelstrom that US and European-dominated global development has bequeathed us over the last century, a number of East Asian countries and territories have progressively stepped and have risen to become prominent and, sometimes, decisive players: Japan from the late 19th century; South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore from the 1960s and perhaps Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia today. Most significant for our contemporary epoch, however, has been the re-emergence of China as a world economic and political power; a re-emergence that perhaps heralds a new phase of global development: a ‘Global-Asian Era’. -

Stuart Hall Bibliography 27-02-2018

Stuart Hall (3 February 1932 – 10 February 2014) Editor — Universities & Left Review, 1957–1959. — New Left Review, 1960–1961. — Soundings, 1995–2014. Publications (in chronological order) (1953–2014) Publications are given in the following order: sole authored works first, in alphabetical order. Joint authored works are then listed, marked ‘with’, and listed in order of co- author’s surname, and then in alphabetical order. Audio-visual material includes radio and television broadcasts (listed by date of first transmission), and film (listed by date of first showing). 1953 — ‘Our Literary Heritage’, The Daily Gleaner, (3 January 1953), p.? 1955 — ‘Lamming, Selvon and Some Trends in the West Indian Novel’, Bim, vol. 6, no. 23 (December 1955), 172–78. — ‘Two Poems’ [‘London: Impasse by Vauxhall Bridge’ and ‘Impasse: Cities to Music Perhaps’], BIM, vol. 6, no. 23 (December 1955), 150–151. 1956 — ‘Crisis of Conscience’, Oxford Clarion, vol. 1, no. 2 (Trinity Term 1956), 6–9. — ‘The Ground is Boggy in Left Field!’ Oxford Clarion, vol. 1, no 3 (Michaelmas Term, 1956), 10–12. 1 — ‘Oh, Young Men’ (Extract from “New Landscapes for Aereas”), in Edna Manley (ed.), Focus: Jamaica, 1956 (Kingston/Mona: The Extra-Mural Department of University College of the West Indies, 1956), p. 181. — ‘Thus, At the Crossroads’ (Extract from “New Landscapes for Aereas”), in Edna Manley (ed.), Focus: Jamaica, 1956 (Kingston/Mona: The Extra-Mural Department of University College of the West Indies, 1956), p. 180. — with executive members of the Oxford Union Society, ‘Letter: Christmas Card Aid’, The Times, no. 53709 (8 December 1956), 7. 1957 — ‘Editorial: “Revaluations”’, Oxford Clarion: Journal of the Oxford University Labour Club, vol. -

Labor History Subject Catalog

Labor History Catalog of Microform (Research Collections, Serials, and Dissertations) www.proquest.com/en-US/catalogs/collections/rc-search.shtml [email protected] 800.521.0600 ext. 2793 or 734.761.4700 ext. 2793 USC009-03 updated May 2010 Table of Contents About This Catalog ............................................................................................... 2 The Advantages of Microform ........................................................................... 3 Research Collections............................................................................................. 4 African Labor History .......................................................................................................................................5 Asian Labor History ..........................................................................................................................................6 British Labor History ........................................................................................................................................8 Canadian Labor History ................................................................................................................................. 20 Caribbean Labor History ................................................................................................................................ 22 French Labor History ...................................................................................................................................... 24 Globalization -

When China Rules the World by Martin Jacques Getting Your View the Spectator, London of the World from by Jonathan Mirsky a Marxist!

BOOK REVIEW Be Careful about When China Rules the World by Martin Jacques Getting Your View The Spectator, London of the World from By Jonathan Mirsky a Marxist! This long and repetitive book is exactly about what it says on the cover. Unlike Martin Jacques, I hesitate to say the same thing again and again, but his point is that the Chinese have a very long, tenacious, unified, and enduring culture that is overtaking the ‘West’ — he means the United States, a country of recent origin compared to the 5,000-year-old Chinese civilisation-state. Some time in the mid-term future the Chinese will be global masters. Jacques, a well-known journalist, once-editor of Marxism Today and now a columnist for the Guardian and the New Statesman, lived for some years in Japan, Hong Kong, and China. In his introduction he thanks dozens of friends and colleagues, some of whom, he says, saved him from ‘mistakes and indiscretions’. I don’t know what he was saved from, but what remains is peppered with basic errors of fact so serious that they mar the reasonable things he says. While not original, these include a potted account, repeated many times, of China’s post-Mao economy, an overview of China’s traditional technological developments that I assumed owed much to Joseph Needham’s multi- volume study of that subject, but there is no mention of this in the bibliography; China’s recent entry into the multi-state system; its influence on the rest of the Third World; the recent loss of status, economically and in reputation of ‘the West’, by which, as I say, he usually means the US; Chinese cultural-physical racism. -

Welsh Communist Party) Papers (GB 0210 PEARCE)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Bert Pearce (Welsh Communist Party) Papers (GB 0210 PEARCE) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 05, 2017 Printed: May 05, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH This description follows NLW guidelines based on ISAD(G) Second Edition; AACR2; and LCSH. https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/bert-pearce-welsh-communist-party- papers-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/bert-pearce-welsh-communist-party-papers-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Bert Pearce (Welsh Communist Party) Papers Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 5 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................ -

Revisionism: the Politics of the CPGB Past & Present

Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line Revolutionary Communist League of Britain Revisionism: The Politics of the CPGB Past & Present First Published: RCL Briefing, 1989 Transcription, Editing and Markup: Sam Richards and Paul Saba Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above. Revisionism: The Politics of the CPGB Past & Present Foreword The articles in this briefing are initial contributions to an assessment of revisionism in Britain. It was recognition of the political damage of revisionism that bought forth a counter political current of anti-revisionist activists. Many of these received moral and ideological support from the Sino-Soviet Polemics of the early 1960s. In Britain, like elsewhere in North America and Europe, that Polemic did not see the political destruction of the o1d Moscow oriented parties. In Britain the anti-revisionist movement failed to unite with some activists expelled from the CPGB, and others remaining inside seeking to return the CPGB to Leninist basics. The new ML groups that were formed emerged largely out of the radicalised petty bourgeois youth with a sprinkling of communist veterans. Most of these groups back-dated their ideological birth to the Polemic on the General Line of the International Communist Movement. A source of strength to the adherents of such groups was Mao's China. -

Towards a Unified Theory Analysing Workplace Ideologies: Marxism And

Marxism and Racial Oppression: Towards a Unified Theory Charles Post (City University of New York) Half a century ago, the revival of the womens movementsecond wave feminismforced the revolutionary left and Marxist theory to revisit the Womens Question. As historical materialists in the 1960s and 1970s grappled with the relationship between capitalism, class and gender, two fundamental positions emerged. The dominant response was dual systems theory. Beginning with the historically correct observation that male domination predates the emergence of the capitalist mode of production, these theorists argued that contemporary gender oppression could only be comprehended as the result of the interaction of two separate systemsa patriarchal system of gender domination and the capitalist mode of production. The alternative approach emerged from the debates on domestic labor and the predominantly privatized character of the social reproduction of labor-power under capitalism. In 1979, Lise Vogel synthesized an alternative unitary approach that rooted gender oppression in the tensions between the increasingly socialized character of (most) commodity production and the essentially privatized character of the social reproduction of labor-power. Today, dual-systems theory has morphed into intersectionality where distinct systems of class, gender, sexuality and race interact to shape oppression, exploitation and identity. This paper attempts to begin the construction of an outline of a unified theory of race and capitalism. The paper begins by critically examining two Marxian approaches. On one side are those like Ellen Meiksins Wood who argued that capitalism is essentially color-blind and can reproduce itself without racial or gender oppression. On the other are those like David Roediger and Elizabeth Esch who argue that only an intersectional analysis can allow historical materialists to grasp the relationship of capitalism and racial oppression. -

What's Left of the Left: Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging

What’s Left of the Left What’s Left of the Left Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging Times Edited by James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Duke University Press Durham and London 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: The New World of the Center-Left 1 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Part I: Ideas, Projects, and Electoral Realities Social Democracy’s Past and Potential Future 29 Sheri Berman Historical Decline or Change of Scale? 50 The Electoral Dynamics of European Social Democratic Parties, 1950–2009 Gerassimos Moschonas Part II: Varieties of Social Democracy and Liberalism Once Again a Model: 89 Nordic Social Democracy in a Globalized World Jonas Pontusson Embracing Markets, Bonding with America, Trying to Do Good: 116 The Ironies of New Labour James Cronin Reluctantly Center- Left? 141 The French Case Arthur Goldhammer and George Ross The Evolving Democratic Coalition: 162 Prospects and Problems Ruy Teixeira Party Politics and the American Welfare State 188 Christopher Howard Grappling with Globalization: 210 The Democratic Party’s Struggles over International Market Integration James Shoch Part III: New Risks, New Challenges, New Possibilities European Center- Left Parties and New Social Risks: 241 Facing Up to New Policy Challenges Jane Jenson Immigration and the European Left 265 Sofía A. Pérez The Central and Eastern European Left: 290 A Political Family under Construction Jean- Michel De Waele and Sorina Soare European Center- Lefts and the Mazes of European Integration 319 George Ross Conclusion: Progressive Politics in Tough Times 343 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Bibliography 363 About the Contributors 395 Index 399 Acknowledgments The editors of this book have a long and interconnected history, and the book itself has been long in the making. -

Stuart Hall, Culturalism, Fordism and Post-Fordism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CommonKnowledge Pacific University CommonKnowledge Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Social Work Faculty Scholarship (CAS) 2017 New Times: Stuart Hall, Culturalism, Fordism and Post-Fordism Christopher D. Wilkes Pacific University Recommended Citation Wilkes, Christopher D., "New Times: Stuart Hall, Culturalism, Fordism and Post-Fordism" (2017). Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Social Work. 4. https://commons.pacificu.edu/sasw/4 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship (CAS) at CommonKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Social Work by an authorized administrator of CommonKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. New Times: Stuart Hall, Culturalism, Fordism and Post-Fordism Description 'Stuart Hall and the Culturalist Turn' is an extended version of Chapter Five from 'The State: a Biography', forthcoming, from Cambridge Scholars Press. Rights Terms of use for work posted in CommonKnowledge. This book chapter is available at CommonKnowledge: https://commons.pacificu.edu/sasw/4 New Times Stuart Hall, Culturalism, Fordism and Post-Fordism Introduction : the Winter of Discontent and the Rise of Thatcherism. In 1979, the year of Poulantzas’s death, and in the wake of a disastrous period of Labour rule in Britain, Margaret Thatcher came to power as the first woman Prime Minister in U.K. history, and with a platform of reforms in hand that was to change the nature of British politics for decades to come. This new régime, rapidly labelled Thatcherism, sought to deal with major problems of unemployment and a long-standing economic crisis. -

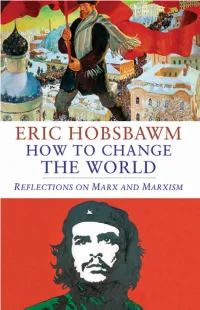

How to Change the World Also by Eric Hobsbawm

How to Change the World Also by Eric Hobsbawm The Age of Revolution 1789–1848 The Age of Capital 1848–1875 The Age of Empire 1875–1914 The Age of Extremes 1914–1991 Labouring Men Industry and Empire Bandits Revolutionaries Worlds of Labour Nations and Nationalism Since 1780 On History Uncommon People The New Century Globalisation, Democracy and Terrorism Interesting Times How to Change the World Reflections on Marx and Marxism Eric Hobsbawm New Haven & London To the memory of George Lichtheim This collection first published 2011 in the United States by Yale University Press and in Great Britain by Little, Brown. Copyright © 2011 by Eric Hobsbawm. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] (U.S. office) or [email protected] (U.K. office). Typeset in Baskerville by M Rules. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Control Number: 2011927314 ISBN 978-0-300-17616-2 (hardcover : alk. paper) A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Foreword vii PART I: MARX AND ENGELS 1 Marx Today 3 2 Marx, -

When China Rules the World

When China Rules the World 803P_pre.indd i 5/5/09 16:50:52 803P_pre.indd ii 5/5/09 16:50:52 martin jacques When China Rules the World The Rise of the Middle Kingdom and the End of the Western World ALLEN LANE an imprint of penguin books 803P_pre.indd iii 5/5/09 16:50:52 ALLEN LANE Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London wc2r orl, England Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada m4p 2y3 (a division of Pearson Canada Inc.) Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offi ces: 80 Strand, London wc2r orl, England www.penguin.com First published 2009 1 Copyright © Martin Jacques, 2009 The moral right of the author has been asserted All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book Typeset in 10.5/14pt Sabon by Palimpsest Book Production Limited, Grangemouth, Stirlingshire Printed in England by XXX ISBN: 978–0–713–99254–0 www.greenpenguin.co.uk Penguin Books is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. -

Alex Callinicos the Politics of Marxism Today

Alex Callinicos The politics of Marxism Today (Summer 1985) From International Socialism 2 : 29, Summer 1985. Transcribed by Christian Høgsbjerg. Marked up by Einde O’ Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On- Line (ETOL). Marxism Today, the theoretical and discussion journal of the Communist Party of Great Britain, has been transformed since 1977 from a rather dull monthly of interest only, if at all, to CP members to a lively, attractively produced and controversial magazine widely read on the left. The change has something to do with style – the replacement of old Party workhorse James Klugmann with the present editor, Martin Jacques. Fundamentally, however, it reflects the emergence of a new theoretical and political current, the Eurocommunist wing of the party, which has not only played a major role in precipitating the present split in the CP, but seeks to bring about a more general re-alignment of the left. Ralph Miliband aptly described the politics of this tendency recently when he called it the ‘new revisionism’, marking ‘a very pronounced retreat from some socialist positions.’ [1] The essence of this retreat was correctly summarized by some supporters of the Morning Star wing of the Communist Party, the authors of the widely discussed pamphlet Class Politics: ‘there has been a shift away from, even an abandonment of, the central role of class and class conflict in the analysis and formation of political strategy.’ [2] There are three reasons for discussing the politics of the new revisionism in this journal. The first is that theirs are not simply ideas formulated by a few left-wing academics with no effect on broader movements and struggles.