The Actuality of Critical Theory in the Netherlands, 1931-1994 By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Peoples’ internationalism Central Asian modernisers, Soviet Oriental studies and cultural revolution in the East (1936- 1977) Jansen, H.E. Publication date 2020 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Jansen, H. E. (2020). Peoples’ internationalism: Central Asian modernisers, Soviet Oriental studies and cultural revolution in the East (1936-1977). General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 Bibliography. - 216 - I. Archival sources From Russia: State Archive of the Russian Federation (GARF) fond 9540 Soviet Committee for Solidarity with Courtiers of Asia and Africa, 1956-91 opis 1, Presidiumsopis, delo 2. Russian State Archive of Contemporary History (RGANI) fond 5 CPSU Central Committee opis 17, delo 425. -

1964 Jaargang 19 (Xix)

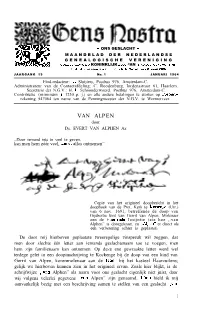

- ONS GESLACHT - MAANDBLAD DER NEDERLANDSE GENEALOGISCHE VERENIGING OOEDGEKEURD 312 KONINKLIJK BESL. “AN 16 A”O”STUS reaa. YO. 85 Llc.tstel,jk podpeKe”rd 51, KO”i”kli,k a.,,uit van J .+r,, ,833 JAARGANG 19 No. 1 JANUARI 1964 Eind-redacteur: J. Sluijters, Postbus 976, Amsterdam-C. Administrateur van de Contactafdeling: C. Roodenburg, Iordensstraat 61, Haarlem. Secretaris der N.G.V.: H. J. Schoonderwoerd, Postbus 976, Amsterdam-C. Contributie (minimum f 1230 p. j.) en alle andere betalingen te storten op Postgiro- rekening 547064 ten name van de Penningmeester der N.G.V. te Wormerveer. VAN ALPEN door Ds. EVERT VAN ALPHEN Az ,,Door iemand iets te veel te geven, kan men hem zéér veel, zoniet alles ontnemen” Copie van het origineel doopbericht in het doopboek van de Prot. Kerk te Kortenge (Utr.) van 6 nov. 1691, betreffende de doop van Gijsbertie kint van Gerrit van Alpen, Molenaer aen de Haer ende Josijntie (zie hoe ,,van Alphen” is doorgekrast, en ,,Alpen” er direct als een verbetering achter is geplaatst). De door mij hierboven geplaatste tweeregelige zinspreuk wil zeggen, dat men door slechts één letter aan iemands geslachtsnaam toe te voegen, men hem zijn familienaam kan ontnemen. Op deze ene gewraakte letter werd wel terdege gelet in een doopinschrijving te Kockenge bij de doop van een kind van Gerrit van Alpen, korenmolenaar aan de Haer bij het kasteel Haarzuilens; gelijk we hierboven kunnen zien in het origineel ervan. Zoals hier blijkt, is de schrijfwijze ,,van Alphen” als naam voor ons geslacht eigenlijk niet juist, daar wij volgens velerlei gegevens ,,van Alpen” zijn genaamd. -

Kopstukken Van De Nsb

KOPSTUKKEN VAN DE NSB Marcel Bergen & Irma Clement Marcel Bergen & Irma Clement KOPSTUKKEN VAN DE NSB UITGEVERIJ MOKUMBOOKS Inhoud Inleiding 4 Nationaalsocialisme en fascisme in Nederland 6 De NSB 11 Anton Mussert 15 Kees van Geelkerken 64 Meinoud Rost van Tonningen 98 Henk Feldmeijer 116 Max Blokzijl 132 Robert van Genechten 155 Johan Carp 175 Arie Zondervan 184 Tobie Goedewaagen 198 Henk Woudenberg 210 Evert Roskam 222 Noten 234 Literatuur 236 Colofon 238 dwang te overtuigen van de Groot-Germaanse gedachte. Het gevolg is dat Mussert zich met enkele getrouwen terug- trekt op het hoofdkwartier aan de Maliebaan in Utrecht en de toenemende druk probeert te pareren met notities, toespraken en concessies. Naarmate de bezetting voortduurt nemen de concessies die Mussert aan de Duitse bezetter doet toe. Inleiding De Nationaal Socialistische Beweging (NSB) speelt tijdens Het Rijkscommissariaat de Tweede Wereldoorlog een opmerkelijke rol. Op 14 mei 1940 aanvaardt Arthur Seyss-Inquart in de De NSB, die op 14 december 1931 in Utrecht is opgericht in Ridderzaal de functie van Rijkscommissaris voor de een zaaltje van de Christelijke Jongenmannen Vereeniging, bezette Nederlandse gebieden. Het Rijkscommissariaat vecht tijdens haar bestaan een richtingenstrijd uit. Een strijd is een civiel bestuursorgaan en bestaat verder uit: die gaat tussen de Groot-Nederlandse gedachte, die streeft – Friederich Wimmer (commissaris-generaal voor be- naar een onafhankelijk Groot Nederland binnen een Duits stuur en justitie en plaatsvervanger van Seyss-Inquart). Rijk en de Groot-Germaanse gedachte,waarin Nederland – Hans Fischböck (generaal-commissaris voor Financiën volledig opgaat in een Groot-Germaans Rijk. Niet alleen de en Economische Zaken). richtingenstrijd maakt de NSB politiek vleugellam. -

From Artist-As-Leader to Leader-As-Artist Is a Critical Examination of the Image of Contemporary Leadership and Its Roots

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UVH Repository from from from artist - as artist-as-leader - leader to to to leader leader-as-artist - as From artist-as-leader to leader-as-artist is a critical examination of - artist the image of contemporary leadership and its roots. Through the lens of modern management texts, Pieterse explores the the dutch Beat poet and performer link between contemporary management speak and the artistic critique of the avant-garde movements of the 1950s in the Netherlands, simon Vinkenoog as exemplar of leadership focusing specifically on the Dutch Fiftiers group, the Cobra movement and 1960s countercultural activism. Subsequently, a neo- in contemporary organizations management discourse is generated whereby the figure of the artist becomes the model for the modern leader: charismatic, visionary, intuitive, mobile, creative, cooperative, open to taking risks and strong at networking. Such a discourse appeals to the values of self- actualization, freedom, authenticity and “knowledge deriving from personal experience” (Boltanski and Chiapello 2007: 113), the very values of the artistic critique that have been absorbed into modern- day capitalism. Pieterse explores this transformation of the artistic critique into contemporary leadership rhetoric by unfolding the life and work of ISBN 978-90-818047-1-4 the Dutch Beat poet and performer Simon Vinkenoog, a highly influential leader in the artistic critique. In doing so he examines the dilemmas, paradoxes and contradictions present within contemporary leadership. Vincent Pieterse is a Program Director at de Baak Management Centre, one of the largest management training institutes in the Vincent Pieterse NUR 600 Netherlands. -

A Cape of Asia: Essays on European History

A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 1 a cape of asia A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 2 A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 3 A Cape of Asia essays on european history Henk Wesseling leiden university press A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 4 Cover design and lay-out: Sander Pinkse Boekproductie, Amsterdam isbn 978 90 8728 128 1 e-isbn 978 94 0060 0461 nur 680 / 686 © H. Wesseling / Leiden University Press, 2011 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 5 Europe is a small cape of Asia paul valéry A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 6 For Arnold Burgen A Cape of Asia.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10-10-11 / 11:44 | Pag. 7 Contents Preface and Introduction 9 europe and the wider world Globalization: A Historical Perspective 17 Rich and Poor: Early and Later 23 The Expansion of Europe and the Development of Science and Technology 28 Imperialism 35 Changing Views on Empire and Imperialism 46 Some Reflections on the History of the Partition -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY GENERAL ISSUES RELIGIONS AND PHILOSOPHY FIORANI, ELEONORA. Friedrich Engels e il materialismo dialettico. Feltrinelli Editore, Milano 1971. 272 pp. L. 3000. Engels's Anti-Diihring, Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy and Dialectics of Nature are the writings most elaborated upon by the author, who, refuting efforts to draw a line between Marx and Engels as regards their later followers, stresses Engels's contribution to Marxism. She argues that his contribution to dialectical materialism is still important for a clarification of topical issues, and makes some comments on the vicissitudes of diamat in the USSR. A chronology of Engels's life and an annotated bibliography are appended. HARTMANN, KLAUS. Die Marxsche Theorie. Eine philosophische Unter- suchung zu den Hauptschriften. Walter de Gruyter & Co, Berlin 1970. xii, 593 pp. DM 78.00. The author of this learned study undertakes a re-appraisal of Marx's theory from a purely philosophical angle. He criticizes Popper's theses (and lack of understanding of Hegelianism), but his own refutation of Marxian views brings him closer to Popper's. It is denied that a dialectical process going on in reality could justifiably be made to fit in the chain of historical necessity. Besides Marx's more philosophical writings all his major works, especially Capital, come up for discussion. Interesting are the comments on Marxist and non-Marxist evaluations of our time (Sartre, Habermas etc.). WILDERMUTH, ARMIN. Marx und die Verwirklichung der Philosophic. Martinus Nijhoff, Den Haag 1970. xii, 852 pp. (in 2 vols.) Hfl. 90.00. "The synthetic unity [of inter-subjective and object-related communications] constitutes the indissoluble process of the 'social movement', the total process of human self-reproduction. -

Newton.Indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 14:45 | Pag

omslag Newton.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 14:45 | Pag. 1 e Dutch Republic proved ‘A new light on several to be extremely receptive to major gures involved in the groundbreaking ideas of Newton Isaac Newton (–). the reception of Newton’s Dutch scholars such as Willem work.’ and the Netherlands Jacob ’s Gravesande and Petrus Prof. Bert Theunissen, Newton the Netherlands and van Musschenbroek played a Utrecht University crucial role in the adaption and How Isaac Newton was Fashioned dissemination of Newton’s work, ‘is book provides an in the Dutch Republic not only in the Netherlands important contribution to but also in the rest of Europe. EDITED BY ERIC JORINK In the course of the eighteenth the study of the European AND AD MAAS century, Newton’s ideas (in Enlightenment with new dierent guises and interpre- insights in the circulation tations) became a veritable hype in Dutch society. In Newton of knowledge.’ and the Netherlands Newton’s Prof. Frans van Lunteren, sudden success is analyzed in Leiden University great depth and put into a new perspective. Ad Maas is curator at the Museum Boerhaave, Leiden, the Netherlands. Eric Jorink is researcher at the Huygens Institute for Netherlands History (Royal Dutch Academy of Arts and Sciences). / www.lup.nl LUP Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. 1 Newton and the Netherlands Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. 2 Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. -

A “Calvinist” Theory of Matter? Burgersdijk and Descartes on Res Extensa

Title Page A “Calvinist” Theory of Matter? Burgersdijk and Descartes on res extensa Giovanni Gellera ORCID IDENTIFIER 0000-0002-8403-3170 Section de philosophie, Université de Lausanne [email protected] The Version of Record of this manuscript has been published and is available in Intellectual History Review volume 28 (2018), issue 2. Published online 24 Novembre 2017. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17496977.2017.1374058 Abstract In the Dutch debates on Cartesianism of the 1640s, a minority believed that some Cartesian views were in fact Calvinist ones. The paper argues that, among others, a likely precursor of this position is the Aristotelian Franco Burgersdijk (1590-1635), who held a reductionist view of accidents and of the essential extension of matter on Calvinist grounds. It seems unlikely that Descartes was unaware of these views. The claim is that Descartes had two aims in his Replies to Arnauld: to show the compatibility of res extensa and the Catholic transubstantiation but also to differentiate the res extensa from some views of matter explicitly defended by some Calvinists. The association with Calvinism will be eventually used polemically against Cartesianism, for example in France. The paper finally suggests that, notwithstanding the points of conflict, the affinities between the theologically relevant theories of accidents, matter and extension ultimately facilitated the dissemination of Cartesianism among the Calvinists. Keywords: Descartes, Burgersdijk, res extensa, accident, Calvinist scholasticism, eucharist 2 G. GELLERA A “Calvinist” Theory of Matter? Burgersdijk and Descartes on res extensa Giovanni Gellera University of Lausanne, Switzerland In 1651 Count Louis Henry of Nassau demanded that the Dutch universities issue public statements on Cartesian philosophy. -

From Squatting to Tactical Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2019 Between the Cracks: From Squatting to Tactical Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993 Amanda S. Wasielewski The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3125 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] BETWEEN THE CRACKS: FROM SQUATTING TO TACTICAL MEDIA ART IN THE NETHERLANDS, 1979–1993 by AMANDA WASIELEWSKI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partiaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of PhiLosophy, The City University of New York 2019 © 2019 AMANDA WASIELEWSKI ALL Rights Reserved ii Between the Cracks: From Squatting to TacticaL Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993 by Amanda WasieLewski This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of PhiLosophy. Date David JoseLit Chair of Examining Committee Date RacheL Kousser Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Marta Gutman Lev Manovich Marga van MecheLen THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Between the Cracks: From Squatting to TacticaL Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993 by Amanda WasieLewski Advisor: David JoseLit In the early 1980s, Amsterdam was a battLeground. During this time, conflicts between squatters, property owners, and the police frequentLy escaLated into fulL-scaLe riots. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae CHRISTIAN JOPPKE CURRENT POSITION Chair in General Sociology, University of Bern (since September 2010) OFFICE ADDRESS University of Bern Institute of Sociology Fabrikstrasse 8 CH-3012 Bern Switzerland Email: [email protected] PREVIOUS POSITIONS 2006-11 Professor of Political Science, American University of Paris 2004-06 Professor, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, International University Bremen (now Jacobs University Bremen) 2003-04 Professor (tenured), Department of Anthropology and Sociology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver 1995-02 Associate Professor (A6 to A5 levels), Department of Political and Social Sciences, European University Institute, Florence 1990-94 Assistant Professor (tenure track), Department of Sociology, University of Southern California EDUCATION 1989 Ph.D. (Sociology) University of California at Berkeley 1984 Diplom (Sociology) Goethe-Universität Frankfurt 1978-80 Sociology, Philosophy, and Economics Freie Universität Berlin GUEST PROFESSORSHIPS, FELLOWSHIPS, CALLS 2017 (Feb.) Distinguished Visiting Fellow, Center of Excellence for National Security (CENS), Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore 2016 Lecturer, Oslo Summer School in Comparative Social Science, University of Oslo 2013-8 Honorary Professor, Department of Political Science and Government, University of Aarhus, Denmark 2013 (Dec.) Visiting Professor, Radzyner School of Law, Interdisciplinary Center 2 (IDC), Herzliya, Israel 2012-3 Fernand Braudel Senior -

The Left in Europe

ContentCornelia Hildebrandt / Birgit Daiber (ed.) The Left in Europe Political Parties and Party Alliances between Norway and Turkey Cornelia Hildebrandt / Birgit Daiber (ed.): The Left in Europe. Political Parties and Party Alliances between Norway and Turkey A free paperback copy of this publication in German or English can be ordered by email to [email protected]. © Rosa Luxemburg Foundation Brussels Office 2009 2 Content Preface 5 Western Europe Paul-Emile Dupret 8 Possibilities and Limitations of the Anti-Capitalist Left in Belgium Cornelia Hildebrandt 18 Protests on the Streets of France Sascha Wagener 30 The Left in Luxemburg Cornelia Weissbach 41 The Left in The Netherlands Northern Europe Inger V. Johansen 51 Denmark - The Social and Political Left Pertti Hynynen / Anna Striethorst 62 Left-wing Parties and Politics in Finland Dag Seierstad 70 The Left in Norway: Politics in a Centre-Left Government Henning Süßer 80 Sweden: The Long March to a coalition North Western Europe Thomas Kachel 87 The Left in Brown’s Britain – Towards a New Realignment? Ken Ahern / William Howard 98 Radical Left Politics in Ireland: Sinn Féin Central Europe Leo Furtlehner 108 The Situation of the Left in Austria 3 Stanislav Holubec 117 The Radical Left in Czechia Cornelia Hildebrandt 130 DIE LINKE in Germany Holger Politt 143 Left-wing Parties in Poland Heiko Kosel 150 The Communist Party of Slovakia (KSS) Southern Europe Mimmo Porcaro 158 The Radical Left in Italy between national Defeat and European Hope Dominic Heilig 166 The Spanish Left -

Intelligence, Security and Policing Post-9/11 the UK’S Response to the ‘War on Terror’

Intelligence, Security and Policing Post-9/11 The UK’s Response to the ‘War on Terror’ Edited by Jon Moran and Mark Phythian Intelligence, Security and Policing Post-9/11 9780230_551916_01_prexii.indd i 9/11/2008 6:08:49 PM Also by Jon Moran POLICING THE PEACE IN NORTHERN IRELAND Also by Mark Phythian ARMING IRAQ THE POLITICS OF BRITISH ARMS SALES SINCE 1964 INTELLIGENCE IN AN INSECURE WORLD (with Peter Gill) THE LABOUR PARTY, WAR AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS, 1945–2006 9780230_551916_01_prexii.indd ii 9/11/2008 6:08:49 PM Intelligence, Security and Policing Post-9/11 The UK’s Response to the ‘War on Terror’ Edited By Jon Moran University of Wolverhampton, UK and Mark Phythian University of Leicester, UK 9780230_551916_01_prexii.indd iii 9/11/2008 6:08:49 PM Selection and editorial matter © Jon Moran and Mark Phythian 2008 Individual chapters © their respective authors 2008 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.