University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jeffrey Haus

JEFFREY HAUS Director of Jewish Studies Associate Professor (269)-337-5789 (office) Departments of History and Religion (269)-337-5792 (fax) Kalamazoo College email: [email protected] 1200 Academy Street Kalamazoo, Michigan 49006 ACADEMIC TRAINING Ph.D., Brandeis University, Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies, May 1997. Dissertation: "The Practical Dimensions of Ideology: French Judaism, Jewish Education State in the Nineteenth Century" Specializations: The Jews of France, Modern Jewish History, Church and State in Europe Languages: French, Hebrew, German B.A., University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, 1986, with Distinction, Honors in History. Honors Thesis: "The Ford Administration's Policy Toward the Arab Boycott of Business" TEACHING APPOINTMENTS Associate Professor of History and Religion, Director of Jewish Studies, Kalamazoo College, 2009-present. Assistant Professor of History and Religion, Director of Jewish Studies, Kalamazoo College, 2005-09. Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Religious Studies, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 2002-2005 Visiting Assistant Professor, Jewish Studies Program, Tulane University, 1999-2002 Lecturer, Department of Near Eastern & Judaic Studies, Brandeis University, 1998-1999 Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Judaic and Near Eastern Studies, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, 1997-1998 Lecturer, University of Judaism, Los Angeles, 1996 Haus, p.2 PROFESSIONAL & ADMINISTRATIVE EXPERIENCE Director of Jewish Studies, Kalamazoo College, 2005-present. Chair, History Department, Kalamazoo College, July 2010-present Interim Chair, Religion Department, Kalamazoo College, Winter-Spring, 2010, Winter 2011. Faculty Advisor, Jewish Student Organization, Kalamazoo College, 2005-present. Admissions Committee, Kalamazoo College, 2006-2009. Summer Common Reading Committee, Kalamazoo College, 2006-7. Religion Search Committee, Kalamazoo College, June 2006-February 2007. -

1964 Jaargang 19 (Xix)

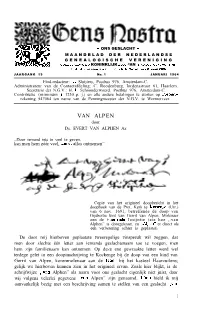

- ONS GESLACHT - MAANDBLAD DER NEDERLANDSE GENEALOGISCHE VERENIGING OOEDGEKEURD 312 KONINKLIJK BESL. “AN 16 A”O”STUS reaa. YO. 85 Llc.tstel,jk podpeKe”rd 51, KO”i”kli,k a.,,uit van J .+r,, ,833 JAARGANG 19 No. 1 JANUARI 1964 Eind-redacteur: J. Sluijters, Postbus 976, Amsterdam-C. Administrateur van de Contactafdeling: C. Roodenburg, Iordensstraat 61, Haarlem. Secretaris der N.G.V.: H. J. Schoonderwoerd, Postbus 976, Amsterdam-C. Contributie (minimum f 1230 p. j.) en alle andere betalingen te storten op Postgiro- rekening 547064 ten name van de Penningmeester der N.G.V. te Wormerveer. VAN ALPEN door Ds. EVERT VAN ALPHEN Az ,,Door iemand iets te veel te geven, kan men hem zéér veel, zoniet alles ontnemen” Copie van het origineel doopbericht in het doopboek van de Prot. Kerk te Kortenge (Utr.) van 6 nov. 1691, betreffende de doop van Gijsbertie kint van Gerrit van Alpen, Molenaer aen de Haer ende Josijntie (zie hoe ,,van Alphen” is doorgekrast, en ,,Alpen” er direct als een verbetering achter is geplaatst). De door mij hierboven geplaatste tweeregelige zinspreuk wil zeggen, dat men door slechts één letter aan iemands geslachtsnaam toe te voegen, men hem zijn familienaam kan ontnemen. Op deze ene gewraakte letter werd wel terdege gelet in een doopinschrijving te Kockenge bij de doop van een kind van Gerrit van Alpen, korenmolenaar aan de Haer bij het kasteel Haarzuilens; gelijk we hierboven kunnen zien in het origineel ervan. Zoals hier blijkt, is de schrijfwijze ,,van Alphen” als naam voor ons geslacht eigenlijk niet juist, daar wij volgens velerlei gegevens ,,van Alpen” zijn genaamd. -

Nueva Sociedad

277 AD D SOCIE A V E U www.nuso.org N Septiembre-Octubre 2018 NUEVA SOCIEDAD 277 COYUNTURA Volver a Marx Elvira Cuadra Lira Nicaragua: ¿una nueva transición en puerta? 200 años después TRIBUNA GLOBAL COYUNTURA Simon Kuper Fútbol: la cultura de la corrupción Elvira Cuadra Lira TEMA CENTRAL TRIBUNA GLOBAL Horacio Tarcus Marx ha vuelto. Paradojas de un regreso inesperado Simon Kuper Martín Abeles / Roberto Lampa Más allá de la «buena» y la «mala» economía política Enzo Traverso Marx, la historia y los historiadores. Una relación para reinventar TEMA CENTRAL Hanjo Kesting Karl Marx como escritor y literato Horacio Tarcus Daniel Luban ¿Ofrece El capital una perspectiva sobre la libertad y la dominación? Martín Abeles / Roberto Lampa Tiziana Terranova Marx en tiempos de algoritmos Enzo Traverso Razmig Keucheyan Marx en la era de la crisis ecológica Volver a Marx. 200 años después Volver Hanjo Kesting Laura Fernández Cordero Feminismos: una revolución que Marx no se pierde Daniel Luban Jean Tible Marx salvaje Dick Howard Cuando la Nueva Izquierda se encontró con Marx Tiziana Terranova Pedro Ribas El proyecto MEGA. Peripecias de la edición crítica de las obras de Marx y Engels Razmig Keucheyan Jacques Paparo En busca de los libros perdidos. Historia y andanzas de una biblioteca Laura Fernández Cordero Britta Marzi / Ann-Katrin Thomm La FES en el 200o aniversario de Karl Marx Jean Tible Dick Howard Pedro Ribas Jacques Paparo Britta Marzi / Ann-Katrin Thomm NUEVA SOCIEDAD es una revista latinoamericana abierta a las corrientes de pensamiento progresista, que aboga por el desarrollo de MAYO-JUNIO 2018 275 276 JULIO-AGOSTO 2018 la democracia política, económica y social. -

The Development of Marxist Thought in the Young Karl Marx Helenhund

DOUGLAS L. BENDELL AWARD THE DEVELOPMENT OF MARXIST THOUGHT IN THE YOUNG KARL MARX HELENHUND Karl Marx was born a contradiction to the world of his time: from a Jewish family, he would become the world's foremost proponent of atheism; from a culture steeped in German romanticism and Hegelian idealist philosophy, he would become the foremost materialist philosopher; from a profligate son and later, profligate husband and father, he would become the economist who spent hours researching the topic of money for the world changing "Das Kapital;" and from this man noted for his culture, intelligence, and arrogance would come the destruction of the old order of privilege through the "Communist Manifesto." Karl Marx was a contradiction to his times, and a revolutionary with a burning desire to change the existing society. His thought, however, was not revolutionary in the sense of being original, but a monumental synthesis of influences in his life, which congealed and culminated in three early works: "Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right," "Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right: Introduction," and the "Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844." Marx was born May 5, 1818 in Trier, a city on the Mosel River • a region renowned for its wine, Roman history, Catholicism, and revolutionary French ideas. Trier, a beautiful city surrounded by vineyards and almost Mediterranean vegetation, had a reputation for wine production from Roman times: Treves (Trier) metropolis, most beautiful city, You, who cultivate the grape, are most pleasing to Bacchus. Give your inhabitants the wines strongest for sweetnessP Marx also had a life-long appreciation of wine; he drank it for medicine when sick, and for pleasure when he could afford it. -

Intermarriage and Jewish Leadership in the United States

Steven Bayme Intermarriage and Jewish Leadership in the United States There is a conflict between personal interests and collective Jewish welfare. As private citizens, we seek the former; as Jewish leaders, however, our primary concern should be the latter. Jewish leadership is entrusted with strengthening the collective Jewish endeavor. The principle applies both to external questions of Jewish security and to internal questions of the content and meaning of leading a Jewish life. Countercultural Messages Two decades ago, the American Jewish Committee (AJC) adopted a “Statement on Mixed Marriage.”1 The statement was reaffirmed in 1997 and continues to represent the AJC’s view regarding Jewish communal policy on this difficult and divisive issue. The document, which is nuanced and calls for plural approaches, asserts that Jews prefer to marry other Jews and that efforts at promoting endogamy should be encouraged. Second, when a mixed marriage occurs, the best outcome is the conversion of the non-Jewish spouse, thereby transforming a mixed marriage into an endogamous one. When conversion is not possible, efforts should be directed at encouraging the couple to raise their children exclusively as Jews. All three messages are countercultural in an American society that values egalitarianism, universalism, and multiculturalism. Preferring endogamy contradicts a universalist ethos of embracing all humanity. Encouraging conversion to Judaism suggests preference for one faith over others. Advocating that children be raised exclusively as Jews goes against multicultural diversity, which proclaims that having two faiths in the home is richer than having a single one. It is becoming increasingly difficult for Jewish leaders to articulate these messages. -

Pázmány Péter Katolikus Egyetem Hittudományi Kar Johann Michael

Pázmány Péter Katolikus Egyetem Hittudományi Kar Johann Michael Sailer a centrum unitatis újrafelfedezője A centrumból élő erkölcs- és lelkipásztori teológia Dissertatio ad Doctoratum Készítette: Takács Gábor Konzulens: Prof. Dr. Puskás Attila Budapest, 2014 2 Bevezetés és köszönetnyilvánítás Korunk jellemrajzát és a modern teológia arculatát nagymértékben meghatározza a felvilágosodás korának lendületes és mindenre kiterjedő, pezsgő átalakulása. A XVIII. sz. második és a XIX. sz. első felében a dél-német területen számos jeles egyházi személyiség nem kis szerepet vállalt az egyházi felvilágosodás folyamatában, teológiai nézeteik, eszméik, felfogásuk jelen volt a II. Vatikáni zsinaton, és így napjaink egyházi életében – mégha burkoltan is – tovább hatnak. Amikor teológiai írásokat és a kapcsolódó társtudományokban keletkezett munkákat felütünk, vagy a lexikonokban az odavágó szócikkeket olvassuk, csakhamar találkozhatunk Johann Michael Sailer (Aresing bei Schrobenhausen, 1751. nov. 17. - Regensburg, 1832. máj. 20.) professzor, a későbbi regensburgi püspök nevével és teológiai munkásságának alkotóelemeivel. A saját egyházi gyökereit is kereső és kiaknázni akaró kutató aligha nélkülözheti és hagyhatja figyelmen kívül e jeles előfutárának munkásságát az erkölcstan, a dogmatika, a lelkipásztori teológia, az egyháztan, a spiritualitás története, az egyháztörténelem, a pedagógia területén. A dolgozat ebben az értelemben biografikus keretbe ágyazva, a gyökerek küzdelmének történetét mutatja be: Sailer megfutott pályája a hitnek és az Egyháznak a saját létjogosultságáért és hiteles megjelenítéséért folytatott küzdelmének története a modern világ kialakulásának kezdetén. Sailer korában, míg sokan az Egyház épületét új alapra kívánták helyezni, addig mások a már felépített épületet kívánták lecserélni - míg az egyik irányzat az épületről, addig a másik az adott alapról feledkezett meg. Sailer a szilárd alapra épített ház, számtalan lakásában folyó életet kívánta megújítani, miután a ház lakójaként felfedezte ennek az életnek és megújításának egyetlen forrását. -

History Bee of Versailles – Final Round Packet

History Bee of Versailles – Final Round Packet 1) This Holocaust survivor and first female minister in French government pushed through her namesake law while serving as Minister of Health in the government of Valery Giscard d’Estaing, where she also championed a law that facilitated access to contraceptives. For the point, name this woman who names the law legalizing abortion in France. ANSWER: Simone Veil (do not accept Simone Weil) 2) After this government arrested General Jean-Charles Pichegru, this government became divided in the aftermath of the Coup of 18 Fructidor. This government’s legislature was consisted of the Counsel of Ancients and Council of Five Hundred, which were stormed by grenadiers in the Coup of 18 Brumaire. The Consulate replaced, for the point, what government which formed after the fall of Robespierre in 1794? ANSWER: French Directory 3) The relics of Saint Thomas Aquinas were donated by Pope Urban V to this city’s Church of the Jacobins. This city was the capital of a kingdom that was conquered by Euric after the Visigoths expanded to Arles and Marseilles, although it was captured and sacked by the Franks under Clovis after the Battle of Vouillé. After Septimania merged with this city’s namesake county, this city became the capital of Languedoc. For the point, name this southern French city, the historic capital of Occitania. ANSWER: Toulouse (or Tolosa) 4) In addition to the Federalist Revolts, the bloodiest of these events was put down by General Turreau’s “flying columns” and failed to take Nantes. During that example of these events, priests who refused to agree to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy were tied to barges and drowned in the Loire. -

Leo Baeck College at the HEART of PROGRESSIVE JUDAISM

Leo Baeck College AT THE HEART OF PROGRESSIVE JUDAISM Leo Baeck College Students – Applications Privacy policy February 2021 Leo Baeck College Registered office • The Sternberg Centre for Judaism • 80 East End Road, London, N3 2SY, UK Tel: +44 (0) 20 8349 5600 • Email: [email protected] www .lbc.ac.uk Registered in England. Registered Charity No. 209777 • Company Limited by Guarantee. UK Company Registration No. 626693 Leo Baeck College is Sponsored by: Liberal Judaism, Movement for Reform Judaism • Affiliate Member: World Union of Progressive Judaism Leo Baeck College AT THE HEART OF PROGRESSIVE JUDAISM A. What personal data is collected? We collect the following personal data during our application process: • address • phone number • e-mail address • religion • nationality We also require the following; • Two current passport photographs. • Original copies of qualifications and grade transcripts. Please send a certified translation if the documents are not in English. • Proof of English proficiency at level CERF B or International English Language Testing System Level 6 or 6+ for those whose mother tongue is not English or for those who need a Tier 4 (General) visa. • Photocopy of the passport pages containing personal information such as nationality Interviewers • All notes taken at the interview will be returned to the applications team in order to ensure this information is stored securely before being destroyed after the agreed timescale. Offer of placement • We will be required to confirm your identity. B. Do you collect any special category data? We collect the following special category data: • Religious belief C. How do you collect my data from me? We use online application forms and paper application forms. -

Archives of the West London Synagogue

1 MS 140 A2049 Archives of the West London Synagogue 1 Correspondence 1/1 Bella Josephine Barnett Memorial Prize Fund 1959-60 1/2 Blackwell Reform Jewish Congregation 1961-67 1/3 Blessings: correspondence about blessings in the synagogue 1956-60 1/4 Bradford Synagogue 1954-64 1/5 Calendar 1957-61 1/6 Cardiff Synagogue 1955-65 1/7 Choirmaster 1967-8 1/8 Choral society 1958 1/9 Confirmations 1956-60 1/10 Edgeware Reform Synagogue 1953-62 1/11 Edgeware Reform Synagogue 1959-64 1/12 Egerton bequest 1964-5 1/13 Exeter Hebrew Congregation 1958-66 1/14 Flower boxes 1958 1/15 Leo Baeck College Appeal Fund 1968-70 1/16 Leeds Sinai Synagogue 1955-68 1/17 Legal action 1956-8 1/18 Michael Leigh 1958-64 1/19 Lessons, includes reports on classes and holiday lessons 1961-70 1/20 Joint social 1963 1/21 Junior youth group—sports 1967 MS 140 2 A2049 2 Resignations 2/1 Resignations of membership 1959 2/2 Resignations of membership 1960 2/3 Resignations of membership 1961 2/4 Resignations of membership 1962 2/5 Resignations of membership 1963 2/6 Resignations of membership 1964 2/7 Resignations of membership Nov 1979- Dec1980 2/8 Resignations of membership Jan-Apr 1981 2/9 Resignations of membership Jan-May 1983 2/10 Resignations of membership Jun-Dec 1983 2/11 Synagogue laws 20 and 21 1982-3 3 Berkeley group magazines 3/1 Berkeley bulletin 1961, 1964 3/2 Berkeley bulletin 1965 3/3 Berkeley bulletin 1966-7 3/4 Berkeley bulletin 1968 3/5 Berkeley bulletin Jan-Aug 1969 3/6 Berkeley bulletin Sep-Dec 1969 3/7 Berkeley bulletin Jan-Jun 1970 3/8 Berkeley bulletin -

Legislative Assembly Approve Laws/Declarations of War Must Pay Considerable Taxes to Hold Office

Nat’l Assembly’s early reforms center on the Church (in accordance with Enlightenment philosophy) › Take over Church lands › Church officials & priests now elected & paid as state officials › WHY??? --- proceeds from sale of Church lands help pay off France’s debts This offends many peasants (ie, devout Catholics) 1789 – 1791 › Many nobles feel unsafe & free France › Louis panders his fate as monarch as National Assembly passes reforms…. begins to fear for his life June 1791 – Louis & family try to escape to Austrian Netherlands › They are caught and returned to France National Assembly does it…. after 2 years! Limited Constitutional Monarchy: › King can’t proclaim laws or block laws of Assembly New Constitution establishes a new government › Known as the Legislative Assembly Approve laws/declarations of war must pay considerable taxes to hold office. Must be male tax payer to vote. Problems persist: food, debt, etc. Old problems still exist: food shortages & gov’t debt Legislative Assembly can’t agree how to fix › Radicals (oppose monarchy & want sweeping changes in gov’t) sit on LEFT › Moderates (want limited changes) sit in MIDDLE › Conservatives (uphold limited monarchy & want few gov’t changes) sit on RIGHT Emigres (nobles who fled France) plot to undo the Revolution & restore Old Regime Some Parisian workers & shopkeepers push for GREATER changes. They are called Sans-Culottes – “Without knee britches” due to their wearing of trousers Monarchs & nobles across Europe fear the revolutionary ideas might spread to their countries Austria & Prussia urge France to restore Louis to power So the Legislative Assembly ………. [April 1792] Legislative Assembly declares war against Prussia and Austria › Initiates the French Revolutionary Wars French Revolutionary Wars: series of wars, from 1792-1802. -

Fair Shares for All

FAIR SHARES FOR ALL JACOBIN EGALITARIANISM IN PRACT ICE JEAN-PIERRE GROSS This study explores the egalitarian policies pursued in the provinces during the radical phase of the French Revolution, but moves away from the habit of looking at such issues in terms of the Terror alone. It challenges revisionist readings of Jacobinism that dwell on its totalitarian potential or portray it as dangerously Utopian. The mainstream Jacobin agenda held out the promise of 'fair shares' and equal opportunities for all in a private-ownership market economy. It sought to achieve social justice without jeopardising human rights and tended thus to complement, rather than undermine, the liberal, individualist programme of the Revolution. The book stresses the relevance of the 'Enlightenment legacy', the close affinities between Girondins and Montagnards, the key role played by many lesser-known figures and the moral ascendancy of Robespierre. It reassesses the basic social and economic issues at stake in the Revolution, which cannot be adequately understood solely in terms of political discourse. Past and Present Publications Fair shares for all Past and Present Publications General Editor: JOANNA INNES, Somerville College, Oxford Past and Present Publications comprise books similar in character to the articles in the journal Past and Present. Whether the volumes in the series are collections of essays - some previously published, others new studies - or mono- graphs, they encompass a wide variety of scholarly and original works primarily concerned with social, economic and cultural changes, and their causes and consequences. They will appeal to both specialists and non-specialists and will endeavour to communicate the results of historical and allied research in readable and lively form. -

The Actuality of Critical Theory in the Netherlands, 1931-1994 By

The Actuality of Critical Theory in the Netherlands, 1931-1994 by Nicolaas Peter Barr Clingan A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Martin E. Jay, Chair Professor John F. Connelly Professor Jeroen Dewulf Professor David W. Bates Spring 2012 Abstract The Actuality of Critical Theory in the Netherlands, 1931-1994 by Nicolaas Peter Barr Clingan Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Martin E. Jay, Chair This dissertation reconstructs the intellectual and political reception of Critical Theory, as first developed in Germany by the “Frankfurt School” at the Institute of Social Research and subsequently reformulated by Jürgen Habermas, in the Netherlands from the mid to late twentieth century. Although some studies have acknowledged the role played by Critical Theory in reshaping particular academic disciplines in the Netherlands, while others have mentioned the popularity of figures such as Herbert Marcuse during the upheavals of the 1960s, this study shows how Critical Theory was appropriated more widely to challenge the technocratic directions taken by the project of vernieuwing (renewal or modernization) after World War II. During the sweeping transformations of Dutch society in the postwar period, the demands for greater democratization—of the universities, of the political parties under the system of “pillarization,” and of