The Development of Marxist Thought in the Young Karl Marx Helenhund

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

OPENINGSFILM DOOR GILLES COULIER Volledig Gedraaid in Oostende! KINEPOLIS & BNP PARIBAS FORTIS PRESENTEREN

Inclusief handig PROGRAMMA SCHEMA GASTLAND NEDERLAND “FILM ZAL DE WERELD NIET REDDEN, MAAR Deze bijlage valt niet onder de verantwoordelijkheid van de redactie van De Standaard • V.U. Peter Craeymeersch - Monacoplein 2 - 8400 Oostende • Foto © Pieter Clicteur Photography Photography Clicteur © Pieter • Foto 2 - 8400 Oostende - Monacoplein Craeymeersch Peter • V.U. vanDeze bijlage valt De Standaard onder de verantwoordelijkheid van niet de redactie KAN DE WERELD WEL VERANDEREN, AL WAS HET MAAR VOOR EVEN.” Master Wim Opbrouck CARGO OPENINGSFILM DOOR GILLES COULIER VOLLEDIG GEDRAAID IN OOSTENDE! KINEPOLIS & BNP PARIBAS FORTIS PRESENTEREN OPERA in de cinema seizoen 2017 / 2018 INHOUD Voorwoord 4 LEGENDE 7/10/2017 NORMA De Master aan het woord 5 Vincenzo Bellini 14/10/2017 DIE ZAUBERFLÖTE Het festival 6 AANWEZIGHEID CAST W.A. Mozart Gastland Nederland 7 18/11/2017 THE EXTERMINATING ANGEL AUDIODESCRIPTIE Thomas Adès Sterleggingen - Outstanding Achievement Awards 8 27/1/2018 TOSCA Programma 9 Giacomo Puccini GEEN NL ONDERTITELING Openingsfilm 9 10/2/2018 L’ELISIR D’AMORE Gaetano Donizetti Avant-premières 11 AVANT-PREMIÈRE 24/2/2018 LA BOHÈME Giacomo Puccini Nederlandse films in première 19 GASTLAND NEDERLAND 10/3/2018 SEMIRAMIDE Slotfilm 21 FFO17 Gioacchino Rossini 3 Programmaschema 22 31/3/2018 COSI FAN TUTTE LOOK! W.A. Mozart Internationale LOOK! competitie 25 14/4/2018 LUISA MILLER Taste of Europe competitie 27 Giuseppe Verdi TASTE OF EUROPE 28/4/2018 CENDRILLON Series 29 Jules Massenet Master Selectie 30 SERIES Kortfilms 32 MASTER SELECTIE Documentaires 35 Voor het 12e seizoen op rij brengt Kinepolis u 10 spraakmakende opera’s in high definition op groot scherm, terwijl ze live worden opgevoerd in de De Ensors 36 New York Metropolitan Opera. -

“Neusnerian Turn” in Method and the End of the Wissenschaft As We Knew It

The “Neusnerian Turn” in Method and the End of the Wissenschaft as We Knew It Peter J. Haas Over the course of a career marked by extraordinary productivity and the training of virtually a generation of Judaic studies scholars, Jacob Neusner has almost singlehandedly altered the entire methodological orientation of the field of Jewish Studies. I take this occasion to look at this extraordinary Neusnerian turn in method for the field of Jewish Studies. Prior to Jacob Neusner’s work, the greatest paradigm shift in Jewish Studies since the emergence of the talmuds was probably the coalescence of the Wissenschaft des Judenthums movement in the first half of the nineteenth cen- tury. In a broad way, the Wissenschaft brought the methods of German phi- lology into Jewish Studies, or, to put matters the other way around, brought Jewish Studies into conversation with the German “scientific” university dis- course of the time. In a similar vein we can say that the second major shift, which took place over a hundred years later, in the late 1960s and early 1970s was when the methods of the North American academic world were brought to bear on classical rabbinic materials, or, again to restate matters, when Judaic Studies was brought into conversation with modern American higher educa- tion. This is what I referred to above as the “Neusnerian turn.” Before turning to the critical methodological shift in Neusner’s early scholar- ship, it will be helpful to review the older paradigm to which it was responding and which it ultimately overturned. The Wissenschaft des Judenthums had its roots in the Verein für Cultur und Wissenschaft des Judenthums that was estab- lished in 1819 by Leopold Zunz, Eduard Gans, and Isaac Marcus Jost, among others. -

Jewish Philosophical Politics in Germany, 1789–1848 Review

Book Reviews 417 semantic meaning (sometimes exceeding the precepts of the post-hermeneutic theo- retical approach). Given the strong connection between the readings and the specific qualities of the poems, Holzmu¨ller’s readings do not yield abstractly summarizable ‘results,’ per se, but it is worth mentioning a few particular strengths. First, her treat- ment of previous scholarship on the poems (and, in the next section, their settings) is thorough and effective, as for example when she reflects on the claims of a long line of scholars about the “Unantastbarkeit” of “Wandrers Nachtlied II” and lists the words whose removal each claims would destroy the poem (232–233) before explaining the phenomenon as a result of the work’s material-linguistic qualities (233ff.). Moreover, in contrast to many approaches focused on formal structuration, Holzmu¨ller keeps the historical-cultural development and connotations of various forms in view (for ex- ample in her analysis of the relation between lineation in “Wandrers Nachtlied I” and the “Abendlied-Strophe” [200–211]). Finally, her reading of the tensions and conflicts between various schemata for formal organization (in “Wandrers Nachtlied II”) pro- vides a model for readers striving to give non-reductive accounts of formal interac- tions and effects (259–261). The third section, which analyzes and compares settings of the two poems by Johann Friedrich Reichardt, Carl Loewe, Franz Schubert, and Hugo Wolf (“Wandrers Nachtlied I”) and Carl Friedrich Zelter, Schubert, and Robert Schumann (“Wandrers Nachtlied II”), is similarly impressive. Holzmu¨ller acknowledges Goethe’s virtuosic shaping of Sprachklang as a problem or challenge for musical setting (one attested to by Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Johannes Brahms, among others [289]) and reflects on the rarity of music-theoretical analyses that take into account the fact that song settings always involve the interaction of two sound systems (linguistic and musical), not merely the fitting of a (musical) sound system to a thematic (linguistic) content. -

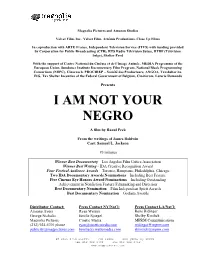

I Am Not Your Negro

Magnolia Pictures and Amazon Studios Velvet Film, Inc., Velvet Film, Artémis Productions, Close Up Films In coproduction with ARTE France, Independent Television Service (ITVS) with funding provided by Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), RTS Radio Télévision Suisse, RTBF (Télévision belge), Shelter Prod With the support of Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, MEDIA Programme of the European Union, Sundance Institute Documentary Film Program, National Black Programming Consortium (NBPC), Cinereach, PROCIREP – Société des Producteurs, ANGOA, Taxshelter.be, ING, Tax Shelter Incentive of the Federal Government of Belgium, Cinéforom, Loterie Romande Presents I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO A film by Raoul Peck From the writings of James Baldwin Cast: Samuel L. Jackson 93 minutes Winner Best Documentary – Los Angeles Film Critics Association Winner Best Writing - IDA Creative Recognition Award Four Festival Audience Awards – Toronto, Hamptons, Philadelphia, Chicago Two IDA Documentary Awards Nominations – Including Best Feature Five Cinema Eye Honors Award Nominations – Including Outstanding Achievement in Nonfiction Feature Filmmaking and Direction Best Documentary Nomination – Film Independent Spirit Awards Best Documentary Nomination – Gotham Awards Distributor Contact: Press Contact NY/Nat’l: Press Contact LA/Nat’l: Arianne Ayers Ryan Werner Rene Ridinger George Nicholis Emilie Spiegel Shelby Kimlick Magnolia Pictures Cinetic Media MPRM Communications (212) 924-6701 phone [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 49 west 27th street 7th floor new york, ny 10001 tel 212 924 6701 fax 212 924 6742 www.magpictures.com SYNOPSIS In 1979, James Baldwin wrote a letter to his literary agent describing his next project, Remember This House. -

'True Democracy' As a Prelude to Communism

Political Philosophy and Public Purpose ‘True Democracy’ as a Prelude to Communism THE MARX OF DEMOCRACY ALEXANDROS CHRYSIS Political Philosophy and Public Purpose Series Editor Michael J. Thompson William Paterson University USA This series offers books that seek to explore new perspectives in social and political criticism. Seeing contemporary academic political theory and philosophy as largely dominated by hyper-academic and overly- technical debates, the books in this series seek to connect the politically engaged traditions of philosophical thought with contemporary social and political life. The idea of philosophy emphasized here is not as an aloof enterprise, but rather a publicly-oriented activity that emphasizes rational refection as well as informed praxis. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/14542 Alexandros Chrysis ‘True Democracy’ as a Prelude to Communism The Marx of Democracy Alexandros Chrysis Panteion University Athens, Greece Political Philosophy and Public Purpose ISBN 978-3-319-57540-7 ISBN 978-3-319-57541-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57541-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017939613 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifcally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microflms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. -

Leopold Zunz and the Invention of Jewish Culture

SCHOLARSHIP OF LITERATURE AND LIFE: LEOPOLD ZUNZ AND THE INVENTION OF JEWISH CULTURE Irene Zwiep Around 1820, a group of Berlin students assembled to found Europe’s first Jewish historical society. The various stages in the society’s brief his- tory neatly mirror the turbulent intellectual Werdegang of its members. The studious, typically Humboldian Wissenschaftszirkel they established in 1816 was changed into the more political Verein zur Verbesserung des Zustandes der Juden im deutschen Bundesstaate in the wake of the HEP!HEP! pogroms of 1819, only to be relabelled the Verein für Cultur und Wissenschaft der Juden two years later, in November 1821. In January 1824, in a session attended by a mere three members, the society’s meet- ings were again suspended. Thus, within less than five years, its ambitious attempts at building an alternative, modern scholarly infrastructure had come to a halt. The new Institut für die Wissenschaft des Judentums that was to serve as the Verein’s headquarters never materialized. Its relentless- ly academic Zeitschrift für die Wissenschaft des Judentums (1822/23) did not survive its first issue. And when trying to strengthen their position within German society, many of its supporters, including first president Eduard Gans (1797-1839) and the ever-ambivalent Heinrich Heine, seem to have preferred smooth conversion to Lutheranism to a prolonged ca- reer in Jewish activism.1 Yet if the Verein’s attempts at establishing a new, comprehensive in- frastructure remained without immediate success, its overall agenda had a lasting impact on modern Jewish discourse. In the early 1820s, Wis- senschaft des Judentums as a form of shared political activism had been doomed to fail; during the following decades, however, a whole genera- 1 For a short history of the Verein, see I. -

MARX's LEGACY REINTERPRETED Karl Heinrich Marx and Political

MARX’S LEGACY REINTERPRETED Karl Heinrich Marx and Political Philosophy Bora Erdağı (Kocaeli University) Abstract Karl Heinrich Marx (1818–1881) is one of the most important refer- ence thinkers for contemporary political theory, contemporary political phi- losophy and contemporary political history. The bases for this view are manifold. The ideas and criticisms presented by Marx are inclined to create friends and foes from the aspect of political praxis; and the most profound elements of his critique on capitalism are, I wish to argue, still valid. These also reflect the potentiality of Marx’s ideas to create alternative perspectives for study of the contemporary world. This ensures the recall and the discus- sion of Marx’s political ideas by alternative political agents in terms of both scientific concern and the contemporary world. Another reason for Marx be- ing a reference thinker of the history of political philosophy—depending on the first two reasons—is that his ideas have been perceptibly “realized” in political practices albeit partially. Thus, whenever the Marxist tradition and its political practices are remembered, the agents of the political arena are obliged to reconsider Marx. In this article, the fact that Marx is considered as a reference thinker in the history of political philosophy will be analyzed in more detail. The basic concepts of his theory will be presented, related to each other with regard to philosophical, real and concrete moments. As con- clusion, a short commentary on Marx’s political theory will be provided. -

Marx's Metascience

Ivar Jonsson Marx's Metascience A Dialogical Approach to his Thought 1 © Félags- og hagvísindastofnun Íslands Reykjavík 2008 Internet publication 2009 ISBN 978-9979-9032-1-5 2 Contents I Introduction 6 II. The story of Marx 9 The Marx family 9 Moving to Bonn 11 Stepping into politics 13 Political refugee 16 Stepping out of political activity 19 Concentrating on economic studies 20 Stepping into politics again 21 Marx’s last decade 27 III. From early texts to the German Ideology 30 The very early articles: 'Wood' and 'Mosel 31 Marx's dialectics: his conception of contradictions 33 Marx's materialist analysis of the political sphere 34 Marx's early social determinism 36 Marx's epistemology; knowledge and political practice 38 The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts 47 Marx's concept of 'labour' 47 Marx's critique of political economy in the Economic 49 and Philosophical Manuscripts Marx's determinism 51 Marx's view of science in general; science 54 and alienation Marx's ideal science; human science 55 Marx's epistemology; the social construction of 57 man's senses and knowledge Knowledge and praxis 61 The ontology of the Economic and 61 Philosophical Manuscripts Marx's relational ontology and his concept of the 'real' 62 Marx's anthropological-philosophical ontology: 64 Man and Nature Marx's concept of the individual in civil society 66 The fatalism of Marx's social ontology of civil society 69 3 The concept of 'labour' as the supersession of the 70 paradox of Marx's anthropological and social ontology Marx's Theses on Feuerbach 71 1) -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

CROSSING BOUNDARY LINES: RELIGION, REVOLUTION, AND NATIONALISM ON THE FRENCH-GERMAN BORDER, 1789-1840 By DAWN LYNN SHEDDEN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2012 1 © 2012 Dawn Shedden 2 To my husband David, your support has meant everything to me 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As is true of all dissertations, my work would have been impossible without the help of countless other people on what has been a long road of completion. Most of all, I would like to thank my advisor, Sheryl Kroen, whose infinite patience and wisdom has kept me balanced and whose wonderful advice helped shape this project and keep it on track. In addition, the many helpful comments of all those on my committee, Howard Louthan, Alice Freifeld, Jessica Harland-Jacobs, Jon Sensbach, and Anna Peterson, made my work richer and deeper. Other scholars from outside the University of Florida have also aided me over the years in shaping this work, including Leah Hochman, Melissa Bullard, Lloyd Kramer, Catherine Griggs, Andrew Shennan and Frances Malino. All dissertations are also dependent on the wonderful assistance of countless librarians who help locate obscure sources and welcome distant scholars to their institutions. I thank the librarians at Eckerd College, George A. Smathers libraries at the University of Florida, the Judaica Collection in particular, Fürstlich Waldecksche Hofbibliothek, Wissenschaftliche Stadtsbibliothek Mainz, Johannes Gutenberg Universitätsbibliothek Mainz, Landeshauptarchiv Koblenz, Stadtarchiv Trier, and Bistumsarchiv Trier. The University of Florida, the American Society for Eighteenth- Century Studies, and Pass-A-Grille Beach UCC all provided critical funds to help me research and write this work. -

Inventing Tradition: on the Formation Of

SHULAMIT VOLKOV INVENTING TRADITION On the Formation of Modern Jewish Culture I Tradition is such a self-evident element in our culture that it seems to require no special explanation. Nevertheless, it has recently become a sub- ject for a prolonged debate in a number of scholarly disciplines1. Repeated efforts to redefine and analyse its meaning led especially to some funda- mental rethinking especially in the field of Volkskunde, in Folklore-studies, in what Americans usually call Anthropology. 2 Interestingly enough, the matter has now invaded other domains, too. The problematising of the con- cept of tradition, together with some of its most common antipodes, such as innovation and modernity, brought about a fundamental rethinking in Kunst- and Literaturwissenschaft3 and, as could only be expected, its reeval- uation is now slowly becoming an issue for historians too. In an ever expanding and changing world, with continuously shifting perspectives, explaining what has always seemed only obvious is no mere luxury. The clearing-up of terminological mess becomes an absolute necessity if one wishes to avoid dogmatism and, worse still, the ever-present danger of provincialism. Terms like tradition must be repeatedly rethought and reconsidered and their meaning reconstructed again and again; they must, in fact, be deconstructed. 1 A shorter version of this study has been the basis of a lecture given in the framework of the Jewish Studies Public Lecture Series of the Central European University on 4 December 2001. 2 See the interesting discussion in D. Ben-Amos, ‘The Seven Strands of Tradition: Varieties in Its Meaning in American Foklore Studies’, Journal of Folklore Research 21 (1984), pp. -

Volume 25, Number 1, Fall 2010 • Marx, Politics… and Punk Roland Boer

Volume 25, Number 1, Fall 2010 • Marx, Politics… and Punk Roland Boer. “Marxism and Eschatology Reconsidered” Mediations 25.1 (Fall 2010) 39-59 www.mediationsjournal.org/articles/marxism-and-eschatology-reconsidered. Marxism and Eschatology Reconsidered Roland Boer Marxism is a secularized Jewish or Christian messianism — how often do we hear that claim? From the time of Nikolai Berdyaev (1937) and Karl Löwith (1949) at least, the claim has grown in authority from countless restatements.1 It has become such a commonplace that as soon as one raises the question of Marxism and religion in a gathering, at least one person will jump at the bait and insist that Marxism is a form of secularized messianism. These proponents argue that Jewish and Christian thought has influenced the Marxist narrative of history, which is but a pale copy of its original: the evils of the present age with its alienation and exploitation (sin) will be overcome by the proletariat (collective redeemer), who will usher in a glorious new age when sin is overcome, the unjust are punished, and the righteous inherit the earth. The argument has served a range of very different purposes since it was first proposed: ammunition in the hands of apostate Marxists like Berdyaev and especially Leszek Kolakowski with his widely influential three-volume work, Main Currents of Marxism;2 a lever to move beyond the perceived inadequacies of Marxism in the hands of Christian theologians eager to assert that theological thought lies at the basis of secular movements like Marxism, however