Assimilation and Profession - the 'Jewish' Mathematician C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MA-302 Advanced Calculus 8

Prof. D. P.Patil, Department of Mathematics, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore Aug-Dec 2002 MA-302 Advanced Calculus 8. Inverse function theorem Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi† (1804-1851) The exercises 8.1 and 8.2 are only to get practice, their solutions need not be submitted. 8.1. Determine at which points a of the domain of definition G the following maps F have differentiable inverse and give the biggest possible open subset on which F define a diffeomorphism. a). F : R2 → R2 with F(x,y) := (x2 − y2, 2xy) . (In the complex case this is the function z → z2.) b). F : R2 → R2 with F(x,y) := (sin x cosh y,cos x sinh y). (In the complex case this is the function z → sin z.) c). F : R2 → R2 with F(x,y) := (x+ y,x2 + y2) . d). F : R3 → R3 with F(r,ϕ,h) := (r cos ϕ,rsin ϕ,h). (cylindrical coordinates) × 2 2 3 3 e). F : (R+) → R with F(x,y) := (x /y , y /x) . xy f). F : R2 → R2 with F(x,y) := (x2 + y2 ,e ) . 8.2. Show that the following maps F are locally invertible at the given point a, and find the Taylor-expansion F(a) of the inverse map at the point upto order 2. a). F : R3 → R3 with F(x,y,z) := − (x+y+z), xy+xz+yz,−xyz at a =(0, 1, 2) resp. a =(−1, 2, 1). ( Hint : The problem consists in approximating the three zeros of the monic polynomial of degree 3 whose coefficients are close to those of X(X−1)(X−2) resp. -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

The Development of Marxist Thought in the Young Karl Marx Helenhund

DOUGLAS L. BENDELL AWARD THE DEVELOPMENT OF MARXIST THOUGHT IN THE YOUNG KARL MARX HELENHUND Karl Marx was born a contradiction to the world of his time: from a Jewish family, he would become the world's foremost proponent of atheism; from a culture steeped in German romanticism and Hegelian idealist philosophy, he would become the foremost materialist philosopher; from a profligate son and later, profligate husband and father, he would become the economist who spent hours researching the topic of money for the world changing "Das Kapital;" and from this man noted for his culture, intelligence, and arrogance would come the destruction of the old order of privilege through the "Communist Manifesto." Karl Marx was a contradiction to his times, and a revolutionary with a burning desire to change the existing society. His thought, however, was not revolutionary in the sense of being original, but a monumental synthesis of influences in his life, which congealed and culminated in three early works: "Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right," "Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right: Introduction," and the "Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844." Marx was born May 5, 1818 in Trier, a city on the Mosel River • a region renowned for its wine, Roman history, Catholicism, and revolutionary French ideas. Trier, a beautiful city surrounded by vineyards and almost Mediterranean vegetation, had a reputation for wine production from Roman times: Treves (Trier) metropolis, most beautiful city, You, who cultivate the grape, are most pleasing to Bacchus. Give your inhabitants the wines strongest for sweetnessP Marx also had a life-long appreciation of wine; he drank it for medicine when sick, and for pleasure when he could afford it. -

Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi

CARL GUSTAV JACOB JACOBI Along with Norwegian Niels Abel, German mathematician Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi (December 10, 1804 – February 18, 1851) was one of the founders of the theory of elliptic functions, which he described in his 1829 work Fundamenta Nova Theoriae Functionum Ellipticarum (New Foundations of the Theory of Elliptic Functions). His achievements in this area drew praise from Joseph-Louis Lagrange, who had spent some 40 years studying elliptic integrals. Jacobi also investigated number theory, mathematical analysis, geometry and differential equations. His work with determinants, in particular the Hamilton-Jacobi theory, a technique of solving a system of partial differential equations by transforming coordinates, is important in the presentation of dynamics and quantum mechanics. V.I. Arnold wrote of the Hamilton-Jacobi method, “… this is the most powerful method known for exact integration.” Born in Potsdam, Jacobi was the son of a prosperous Jewish banker. His older brother Moritz Hermann Jacobi was a well-known physicist and engineer. The latter worked as a leading researcher at the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg. During their lifetimes Moritz was the better known of the two for his work on the practical applications of electricity and especially for his discovery in 1838 of galvanoplastics. Also called electrotyping, it is a process something like electroplating for making duplicate plates of relief, or letterpress, printing. Carl was constantly mistaken for his brother or even worse congratulated for having such a distinguished and accomplished brother. To one such compliment he responded with annoyance, “I am not his brother, he is mine.” Carl Jacobi demonstrated great talent for both languages and mathematics from an early age. -

“Neusnerian Turn” in Method and the End of the Wissenschaft As We Knew It

The “Neusnerian Turn” in Method and the End of the Wissenschaft as We Knew It Peter J. Haas Over the course of a career marked by extraordinary productivity and the training of virtually a generation of Judaic studies scholars, Jacob Neusner has almost singlehandedly altered the entire methodological orientation of the field of Jewish Studies. I take this occasion to look at this extraordinary Neusnerian turn in method for the field of Jewish Studies. Prior to Jacob Neusner’s work, the greatest paradigm shift in Jewish Studies since the emergence of the talmuds was probably the coalescence of the Wissenschaft des Judenthums movement in the first half of the nineteenth cen- tury. In a broad way, the Wissenschaft brought the methods of German phi- lology into Jewish Studies, or, to put matters the other way around, brought Jewish Studies into conversation with the German “scientific” university dis- course of the time. In a similar vein we can say that the second major shift, which took place over a hundred years later, in the late 1960s and early 1970s was when the methods of the North American academic world were brought to bear on classical rabbinic materials, or, again to restate matters, when Judaic Studies was brought into conversation with modern American higher educa- tion. This is what I referred to above as the “Neusnerian turn.” Before turning to the critical methodological shift in Neusner’s early scholar- ship, it will be helpful to review the older paradigm to which it was responding and which it ultimately overturned. The Wissenschaft des Judenthums had its roots in the Verein für Cultur und Wissenschaft des Judenthums that was estab- lished in 1819 by Leopold Zunz, Eduard Gans, and Isaac Marcus Jost, among others. -

Mathematical Genealogy of the Union College Department of Mathematics

Gemma (Jemme Reinerszoon) Frisius Mathematical Genealogy of the Union College Department of Mathematics Université Catholique de Louvain 1529, 1536 The Mathematics Genealogy Project is a service of North Dakota State University and the American Mathematical Society. Johannes (Jan van Ostaeyen) Stadius http://www.genealogy.math.ndsu.nodak.edu/ Université Paris IX - Dauphine / Université Catholique de Louvain Justus (Joost Lips) Lipsius Martinus Antonius del Rio Adam Haslmayr Université Catholique de Louvain 1569 Collège de France / Université Catholique de Louvain / Universidad de Salamanca 1572, 1574 Erycius (Henrick van den Putte) Puteanus Jean Baptiste Van Helmont Jacobus Stupaeus Primary Advisor Secondary Advisor Universität zu Köln / Université Catholique de Louvain 1595 Université Catholique de Louvain Erhard Weigel Arnold Geulincx Franciscus de le Boë Sylvius Universität Leipzig 1650 Université Catholique de Louvain / Universiteit Leiden 1646, 1658 Universität Basel 1637 Union College Faculty in Mathematics Otto Mencke Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Ehrenfried Walter von Tschirnhaus Key Universität Leipzig 1665, 1666 Universität Altdorf 1666 Universiteit Leiden 1669, 1674 Johann Christoph Wichmannshausen Jacob Bernoulli Christian M. von Wolff Universität Leipzig 1685 Universität Basel 1684 Universität Leipzig 1704 Christian August Hausen Johann Bernoulli Martin Knutzen Marcus Herz Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg 1713 Universität Basel 1694 Leonhard Euler Abraham Gotthelf Kästner Franz Josef Ritter von Gerstner Immanuel Kant -

Jewish Philosophical Politics in Germany, 1789–1848 Review

Book Reviews 417 semantic meaning (sometimes exceeding the precepts of the post-hermeneutic theo- retical approach). Given the strong connection between the readings and the specific qualities of the poems, Holzmu¨ller’s readings do not yield abstractly summarizable ‘results,’ per se, but it is worth mentioning a few particular strengths. First, her treat- ment of previous scholarship on the poems (and, in the next section, their settings) is thorough and effective, as for example when she reflects on the claims of a long line of scholars about the “Unantastbarkeit” of “Wandrers Nachtlied II” and lists the words whose removal each claims would destroy the poem (232–233) before explaining the phenomenon as a result of the work’s material-linguistic qualities (233ff.). Moreover, in contrast to many approaches focused on formal structuration, Holzmu¨ller keeps the historical-cultural development and connotations of various forms in view (for ex- ample in her analysis of the relation between lineation in “Wandrers Nachtlied I” and the “Abendlied-Strophe” [200–211]). Finally, her reading of the tensions and conflicts between various schemata for formal organization (in “Wandrers Nachtlied II”) pro- vides a model for readers striving to give non-reductive accounts of formal interac- tions and effects (259–261). The third section, which analyzes and compares settings of the two poems by Johann Friedrich Reichardt, Carl Loewe, Franz Schubert, and Hugo Wolf (“Wandrers Nachtlied I”) and Carl Friedrich Zelter, Schubert, and Robert Schumann (“Wandrers Nachtlied II”), is similarly impressive. Holzmu¨ller acknowledges Goethe’s virtuosic shaping of Sprachklang as a problem or challenge for musical setting (one attested to by Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Johannes Brahms, among others [289]) and reflects on the rarity of music-theoretical analyses that take into account the fact that song settings always involve the interaction of two sound systems (linguistic and musical), not merely the fitting of a (musical) sound system to a thematic (linguistic) content. -

Mathematical Genealogy of the Wellesley College Department Of

Nilos Kabasilas Mathematical Genealogy of the Wellesley College Department of Mathematics Elissaeus Judaeus Demetrios Kydones The Mathematics Genealogy Project is a service of North Dakota State University and the American Mathematical Society. http://www.genealogy.math.ndsu.nodak.edu/ Georgios Plethon Gemistos Manuel Chrysoloras 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Johannes Argyropoulos Guarino da Verona 1444 Università di Padova 1408 Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino Vittorino da Feltre 1462 Università di Firenze 1416 Università di Padova Angelo Poliziano Theodoros Gazes Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo 1477 Università di Firenze 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova Università di Mantova Leo Outers Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Thomas à Kempis Rudolf Agricola Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro François Dubois Jean Tagault Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Pelope Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe -

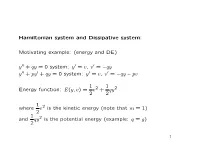

Hamiltonian System and Dissipative System

Hamiltonian system and Dissipative system: Motivating example: (energy and DE) y00 + qy = 0 system: y0 = v, v0 = −qy y00 + py0 + qy = 0 system: y0 = v, v0 = −qy − pv 1 1 Energy function: E(y, v) = v2 + qy2 2 2 1 where v2 is the kinetic energy (note that m = 1) 2 1 and qy2 is the potential energy (example: q = g) 2 1 y00 + qy = 0 d d 1 1 E(y(t), v(t)) = v2(t) + qy2(t) = v(t)v0(t) + qy(t)y0(t) dt dt 2 2 = v(t)(−qy(t)) + qy(t) · v(t) = 0 (energy is conserved) y00 + py0 + qy = 0 d d 1 1 E(y(t), v(t)) = v2(t) + qy2(t) = v(t)v0(t) + qy(t)y0(t) dt dt 2 2 = v(t)(−qy(t) − pv(t)) + qy(t) · v(t) = −p[v(t)]2 ≤ 0 (energy is dissipated) 2 Definition: dx dy = f(x, y), = g(x, y). dt dt If there is a function H(x, y) such that for each solution orbit d (x(t), y(t)), we have H(x(t), y(t)) = 0, then the system is a dt Hamiltonian system, and H(x, y) is called conserved quantity. (or energy function, Hamiltonian) If there is a function H(x, y) such that for each solution orbit d (x(t), y(t)), we have H(x(t), y(t)) ≤ 0, then the system is a dt dissipative system, and H(x, y) is called Lyapunov function. (or energy function) 3 Example: If a satellite is circling around the earth, it is a Hamil- tonian system; but if it drops to the earth, it is a dissipative system. -

Leopold Zunz and the Invention of Jewish Culture

SCHOLARSHIP OF LITERATURE AND LIFE: LEOPOLD ZUNZ AND THE INVENTION OF JEWISH CULTURE Irene Zwiep Around 1820, a group of Berlin students assembled to found Europe’s first Jewish historical society. The various stages in the society’s brief his- tory neatly mirror the turbulent intellectual Werdegang of its members. The studious, typically Humboldian Wissenschaftszirkel they established in 1816 was changed into the more political Verein zur Verbesserung des Zustandes der Juden im deutschen Bundesstaate in the wake of the HEP!HEP! pogroms of 1819, only to be relabelled the Verein für Cultur und Wissenschaft der Juden two years later, in November 1821. In January 1824, in a session attended by a mere three members, the society’s meet- ings were again suspended. Thus, within less than five years, its ambitious attempts at building an alternative, modern scholarly infrastructure had come to a halt. The new Institut für die Wissenschaft des Judentums that was to serve as the Verein’s headquarters never materialized. Its relentless- ly academic Zeitschrift für die Wissenschaft des Judentums (1822/23) did not survive its first issue. And when trying to strengthen their position within German society, many of its supporters, including first president Eduard Gans (1797-1839) and the ever-ambivalent Heinrich Heine, seem to have preferred smooth conversion to Lutheranism to a prolonged ca- reer in Jewish activism.1 Yet if the Verein’s attempts at establishing a new, comprehensive in- frastructure remained without immediate success, its overall agenda had a lasting impact on modern Jewish discourse. In the early 1820s, Wis- senschaft des Judentums as a form of shared political activism had been doomed to fail; during the following decades, however, a whole genera- 1 For a short history of the Verein, see I. -

Inventing Tradition: on the Formation Of

SHULAMIT VOLKOV INVENTING TRADITION On the Formation of Modern Jewish Culture I Tradition is such a self-evident element in our culture that it seems to require no special explanation. Nevertheless, it has recently become a sub- ject for a prolonged debate in a number of scholarly disciplines1. Repeated efforts to redefine and analyse its meaning led especially to some funda- mental rethinking especially in the field of Volkskunde, in Folklore-studies, in what Americans usually call Anthropology. 2 Interestingly enough, the matter has now invaded other domains, too. The problematising of the con- cept of tradition, together with some of its most common antipodes, such as innovation and modernity, brought about a fundamental rethinking in Kunst- and Literaturwissenschaft3 and, as could only be expected, its reeval- uation is now slowly becoming an issue for historians too. In an ever expanding and changing world, with continuously shifting perspectives, explaining what has always seemed only obvious is no mere luxury. The clearing-up of terminological mess becomes an absolute necessity if one wishes to avoid dogmatism and, worse still, the ever-present danger of provincialism. Terms like tradition must be repeatedly rethought and reconsidered and their meaning reconstructed again and again; they must, in fact, be deconstructed. 1 A shorter version of this study has been the basis of a lecture given in the framework of the Jewish Studies Public Lecture Series of the Central European University on 4 December 2001. 2 See the interesting discussion in D. Ben-Amos, ‘The Seven Strands of Tradition: Varieties in Its Meaning in American Foklore Studies’, Journal of Folklore Research 21 (1984), pp. -

THE JACOBIAN MATRIX a Thesis Presented to the Department Of

THE JACOBIAN MATRIX A Thesis Presented to the Department of Mathematics The Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia "*' In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Sheryl A. -Cole June 1970 aAo.xddv PREFACE The purpose of this paper is to investigate the Jacobian matrix in greater depth than this topic is dealt with in any individual calculus text. The history of Carl Jacobi, the man who discovered the determinant, is reviewed in chapter one. The several illustrations in chapter two demon strate tile mechanics of finding the Jacobian matrix. In chapter three the magnification of area under a transformation is related to ti1e Jacobian. The amount of magnification under coordinate changes is also discussed in this chapter. In chapter four a definition of smooth surface area is arrived at by application of the Jacobian. It is my pleasure to express appreciation to Dr. John Burger for all of his assistance in preparing this paper. An extra special thanks to stan for his help and patience. C.G.J. JACOBI (1804-1851) "Man muss immer umkehren" (Man must always invert.) , ,~' I, "1,1'1 TABLE OF CONTENTS . CHAPTER PAGE I. A HISTORY OF JACOBI • • • • • • • • • •• • 1 II. TIlE JACOBIAN .AND ITS RELATED THEOREMS •• • 8 III. TRANSFORMATIONS OF AREA • • • ••• • • • • 14 IV. SURFACE AREA • • ••• • • • • • • ••• • 23 CONCLUSION •• •• ••• • • • • • •• •• •• • • 28 FOOTNOTES •• •• • • • ••• ••• •• •• • • • 30 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • • • • • • • • ·.. • • • • • 32 CHAPTER I A HISTORY OF JACOBI Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi was a prominant mathema tician noted chiefly for his pioneering work in the field of elliptic functions. Jacobi was born December 10, 1804, in Potsdam, Prussia. He was the second of four children born to a very prosperous banker.