How to Reposition the Social, Cultural and Economic Value

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AFL Victoria Player Points System Policy January 2020

AFL Victoria Player Points System Policy January 2020 1 AFL VICTORIA PLAYER POINTS SYSTEM (PPS) POLICY 1. Objective of the Community Club Sustainability Program and PPS Policy The Community Club Sustainability Program (CCSP) subcommittee believes that equalisation of community football competitions is vital for community football. Even and fair competitions lead to interest, which leads to bigger crowds, which leads to stronger clubs and competitions. Even competitions allow supporters and club volunteers the chance to turn up on any given match day with the knowledge that the outcome of the game is uncertain and that their team is a chance of winning. This mindset motivates people to become and remain engaged with their community club and provides rewards and recognition to all those that assist in putting a team out on the field. The philosophy of competition equalisation is accepted in sports all around the world. Professional sporting bodies have accepted practices such as drafts, salary caps, and the like in order to help competitions ensure competitiveness and club sustainability. The objectives of the state PPS Policy are as follows, to: 1. support equalization of community football Competitions; 2. ensure teams fielded in the Competitions are strong and as equally matched as possible; 3. provide the best opportunities for players to develop and display their skills; 4. provide opportunities to compete at a community level within an orderly and fair system; 5. enable team spirit and public support; 6. encourage community and corporate sponsorships of Community Clubs; 7. reduce the inflationary nature of player payments to assist clubs survive financially and reduce financial burden/stress on Clubs; 8. -

The History of NAIDOC Celebrating Indigenous Culture

The History of NAIDOC Celebrating Indigenous Culture latrobe.edu.au CRICOS Provider 00115M Wominjeka Welcome La Trobe University 22 Acknowledgement La Trobe University acknowledges the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nations as the traditional custodians of the land upon which the Bundoora campus is located. LaLa Trobe Trobe University University 33 Acknowledgement We recognise their ongoing connection to the land and value the unique contribution the Wurundjeri people and all Indigenous Australians make to the University and the wider Australian society. LaLa Trobe Trobe University University 44 What is NAIDOC? NAIDOC stands for the ‘National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee’. This committee was responsible for organising national activities during NAIDOC Week and its acronym has since become the name of the week itself. La Trobe University 55 History of NAIDOC NAIDOC Week celebrations are held across Australia each July to celebrate the history, culture and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. NAIDOC is celebrated not only in Indigenous communities, but by Australians from all walks of life. La Trobe University 66 History of NAIDOC 1920-1930 Before the 1920s, Aboriginal rights groups boycotted Australia Day (26 January) in protest against the status and treatment of Indigenous Australians. Several organisations emerged to fill this role, particularly the Australian Aborigines Progressive Association (AAPA) in 1924 and the Australian Aborigines League (AAL) in 1932. La Trobe University 77 History of NAIDOC 1930’s In 1935, William Cooper, founder of the AAL, drafted a petition to send to King George V, asking for special Aboriginal electorates in Federal Parliament. The Australian Government believed that the petition fell outside its constitutional Responsibilities William Cooper (c. -

Day of Mourning – Overview Fact Sheet

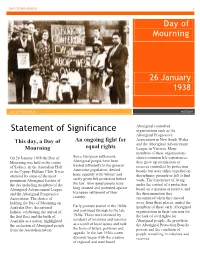

DAY OF MOURNING 1 Day of Mourning 26 January 1938 DAY OF MOURNING HISTORY Aboriginal controlled Statement of Significance organisations such as the Aboriginal Progressive Association in New South Wales An ongoing fight for This day, a Day of and the Aboriginal Advancement Mourning equal rights League in Victoria. Many members of these organisations On 26 January 1938 the Day of Since European settlement, shared common life experiences; Mourning was held in the centre Aboriginal people have been they grew up on missions or of Sydney, in the Australian Hall treated differently to the general reserves controlled by protection at the Cyprus Hellene Club. It was Australian population; denied boards but were either expelled on attended by some of the most basic equality with 'whites' and disciplinary grounds or left to find prominent Aboriginal leaders of rarely given full protection before work. The experience of living the day including members of the the law. Aboriginal people have under the control of a protection Aboriginal Advancement League long resisted and protested against board on a mission or reserve, and and the Aboriginal Progressive European settlement of their the discrimination they Association. The choice of country. encountered when they moved holding the Day of Mourning on away from these places, united the Australia Day, the national Early protests started in the 1840s members of these early Aboriginal holiday celebrating the arrival of and continued through to the late organisations in their concerns for the first fleet and the birth of 1920s. These were initiated by the lack of civil rights for Australia as a nation, highlighted residents of missions and reserves Aboriginal people, the growth in the exclusion of Aboriginal people as a result of local issues and took the Aboriginal Protection Board's from the Australian nation. -

Gladys Nicholls: an Urban Aboriginal Leader in Post-War Victoria

Gladys Nicholls: An Urban Aboriginal Leader in Post-war Victoria Patricia Grimshaw School of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC. 3010 [email protected] Abstract: Gladys Nicholls was an Aboriginal activist in mid-20 th century Victoria who made significant contributions to the development of support networks for the expanding urban Aboriginal community of inner-city Melbourne. She was a key member of a talented group of Indigenous Australians, including her husband Pastor Doug Nicholls, who worked at a local, state and national level to improve the economic wellbeing and civil rights of their people, including for the 1967 Referendum. Those who knew her remember her determined personality, her political intelligence and her unrelenting commitment to building a better future for Aboriginal people. Keywords: Aboriginal women, Aboriginal activism, Gladys Nicholls, Pastor Doug Nicholls, assimilation, Victorian Aborigines Advancement League, 1967 Referendum Gladys Nicholls (1906–1981) was an Indigenous leader who was significant from the 1940s to the 1970s, first, in action to improve conditions for Aboriginal people in Melbourne and second, in grassroots activism for Indigenous rights across Australia. When the Victorian government inscribed her name on the Victorian Women’s Honour Roll in 2008, the citation prepared by historian Richard Broome read as follows: ‘Lady Gladys Nicholls was an inspiration to Indigenous People, being a role model for young women, a leader in advocacy for the rights of Indigenous people as well as a tireless contributor to the community’. 1 Her leadership was marked by strong collaboration and co-operation with like-minded women and men, both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, who were at the forefront of Indigenous reform, including her prominent husband, Pastor (later Sir) Doug Nicholls. -

Tom-Calma.Pdf

CHANCELLOR, Chancellor, I have the honour to present to you Tom Calma, who Council has determined should be awarded the degree of Doctor of Letters Honoris Causa. Mr Tom Calma is an Aboriginal elder from the Kungarakan tribal group and a member of the Iwaidja tribal group whose traditional lands are south-west of Darwin and on the Coburg Peninsula in Northern Territory. As a young man, Mr Calma completed an Associate Diploma of Social Work at the South Australian Institute of Technology and began working for the Australian Government in various roles. In 1980 he joined the then Darwin Community College, one of the predecessor institutions of this University we enjoy today, as a lecturer in the Aboriginal Task Force program. By 1981 he was coordinator of the program and then Head of the academic department. At the time Tom was the first Indigenous Australian appointed to a tenured position at a post-secondary education institution in the Northern Territory and one of the first nationally. In 1986 he rejoined the Australian Government as the Director of the Aboriginal Employment and Training Branch in the Department of Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs based here in Darwin. Following a transfer to Canberra, he became the Executive Officer to the Secretary of the Department of Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs. In this role he chaired and undertook a national review of Aboriginal Education Units in the department. Over the ensuring years he has held a range of positions with the Australian Government, roles that often had a national and international scope. -

SEVEN WOMEN of the 1967 REFERENDUM Project For

SEVEN WOMEN OF THE 1967 REFERENDUM Project for Reconciliation Australia 2007 Dr Lenore Coltheart There are many stories worth repeating about the road to the Referendum that removed a handful of words from Australia’s Constitution in 1967. Here are the stories of seven women that tell how that road was made. INTRODUCING: SHIRLEY ANDREWS FAITH BANDLER MARY BENNETT ADA BROMHAM PEARL GIBBS OODGEROO NOONUCCAL JESSIE STREET Their stories reveal the prominence of Indigenous and non-Indigenous women around Australia in a campaign that started in kitchens and local community halls and stretched around the world. These are not stories of heroines - alongside each of those seven women were many other men and women just as closely involved. And all of those depended on hundreds of campaigners, who relied on thousands of supporters. In all, 80 000 people signed the petition that required Parliament to hold the Referendum. And on 27 May 1967, 5 183 113 Australians – 90.77% of the voters – made this the most successful Referendum in Australia’s history. These seven women would be the first to point out that it was not outstanding individuals, but everyday people working together that achieved this step to a more just Australia. Let them tell us how that happened – how they got involved, what they did, whether their hopes were realised – and why this is so important for us to know. 2 SHIRLEY ANDREWS 6 November 1915 - 15 September 2001 A dancer in the original Borovansky Ballet, a musician whose passion promoted an Australian folk music tradition, a campaigner for Aboriginal rights, and a biochemist - Shirley Andrews was a remarkable woman. -

Speech Brief Closing the Gap – Reconciliation Australia Day National Conference 2013 Brief for Dr Tom Calma AO

Speech Brief Closing the Gap – Reconciliation Australia Day National Conference 2013 Brief for Dr Tom Calma AO 13 June 2013 Closing the Gap—Reconciliation Acknowledgement of country and thanks to: • Aunty Agnes for the welcome Welcoming us to country and acknowledging your ancestors and connection to this land is a very important part of our reconciliation journey. It’s a simple yet powerful way to show respect, and a solid foundation on which to build relationships. Thanks also to: • The Hon Dr Andrew Leigh MP; and • Adam Gilchrist AM, and our next door neighbours in Old Parliament House, the National Australia Day Council] Tribute to Dr Yunupingu Ladies and Gentleman, just over a week ago we lost a great Australian: a song man; an educator; an Australian of the Year. He was a man of many firsts; the first Aboriginal person from the Northern Territory to gain a university degree; the first Aboriginal school principal; the front man of the first band to mix traditional Arnhem Land song cycles with modern rock and dance music to captivate the world. But his passing from kidney disease, which he battled in his adult life, was not a first, and sadly, something all too familiar to Aboriginal people. His death at 56, almost 20 years below the average life expectancy of Australian men, is a stark reminder of the challenges we face to close the gaps between the first Australians and those who now, also call Australia home. It is a reminder that, even an outstanding Australian of the Year—who has trod the world stage, and contributed in so many ways to make this country a better place—even he cannot fully escape the legacies of history. -

Australian Indigenous Petitions

Australian Indigenous Petitions: Emergence and Negotiations of Indigenous Authorship and Writings Chiara Gamboz Dissertation Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences October 2012 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT 'l hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the proiect's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.' Signed 5 o/z COPYRIGHT STATEMENT 'l hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or digsertation in whole or part in the Univercity libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertiation. -

Tom Calma Dr Tom Calma Is an Aboriginal Elder from the Kungarakan Tribal Group and a Member of the Iwaidja Tribal Group in the NT

Tom Calma Dr Tom Calma is an Aboriginal elder from the Kungarakan tribal group and a member of the Iwaidja tribal group in the NT. He has been involved in Indigenous affairs at a local, community, state, national and international level and worked in the public sector for 40 years and is currently on a number of boards and committees focusing on rural and remote Australia, health, education, justice reinvestment and economic development. Dr Calma, a consultant, is the National Coordinator, Tackling Indigenous Smoking where he leads the establishment and mentoring of 57 teams nationally to fight tobacco use by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Dr Calma’s most recent previous position was that of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner at the Australian Human Rights Commission from 2004 to 2010. He also served as Race Discrimination Commissioner from 2004 until 2009. Through his 2005 Social Justice Report, Dr Calma called for the life expectancy gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people to be closed within a generation and laid the groundwork for the Close the Gap campaign. The Close the Gap campaign has effectively brought national attention to achieving health equality for Indigenous people by 2030 and the need to address the social determinants of health to achieve equality. Dr Calma is a strong advocate for Indigenous rights and empowerment and has spearheaded initiatives including the establishment of the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples and Justice Reinvestment. In 2010, Dr Calma was awarded an honorary doctor of letters from Charles Darwin University and in 2011, an honorary doctor of science from Curtin University. -

Interleague 2018 Interleague

INTERLEAGUE 2018 INTERLEAGUE Saturday, May 19, 2018 - Ted Summerton Reserve TRFM Gippsland League v Murray FL / gippsland � physiotherapy group ,,,,.. CLINICAL PILATES STUDIO rDI"t,IH!,/"?°l(e,/ 1300 MYPILATES(1300 697 452) 22 Breed St, Traralgon 78 Smith St, Warragul 21 O Graham St, Wonthaggi pilateschoice.com.au I] ,-ccm 1p1141- @)inm!J>m /OpllmsehOiee SCHEDULE GAME TIMES 10:30am: Worksafe Community Championships Under 18s TRFM Gippsland League v Murray FL 11am: Metricon Intraleague Challenge TRFM Gippsland League 15 & Under’s 12pm: Worksafe Community TRFM Gippsland League v Championships Open Netball Murray Football League TRFM Gippsland League v Murray NA Saturday 19 May, 2018 1pm: Worksafe Community Ted Summerton Reserve, Moe Championships Seniors TRFM Gippsland League v Murray FL RANKING TEAMS VENUE 1 v 2 Geelong FNL v Eastern FL Etihad Stadium 3 v 4 MPNFL v Northern FL Preston City Oval 5 v 6 Ovens & Murray FL v Western RFL Yarrawonga JC Lowe Oval 7 v 8 Ballarat FNL v Goulburn Valley L MCG 9 v 10 Hampden FNL v Bendigo FNL Warrnambool Reid Oval 11 v 12 AFL Yarra Ranges v South East FNL Beaconsfield 13 v 14 Murray FL v Gippsland L Ted Summerton Reserve- Moe 15 v 16 Bellarine FNL v Wimmera FNL Horsham City Oval 17 v 18 Central Murray FNL v Sunraysia FNL Swan Hill Recreation Reserve 19 v 20 Geelong DFL v Heathcote DFL North Geelong 21 v 22 Southern FNL v North Central FL Boort FNC 23 v 24 Riddell DFNL v Central Highlands FL Bungaree 25 v 26 MCDFNL v West Gippsland FNL Garfield 27 v 28 Horsham DFNL v Ellinbank DFL Ballarat City Oval 29 v 30 Kyabram DFNL v Colac DFNL Central Reserve Colac 31 v 32 Golden Rivers FL v Loddon Valley DFL Queen Elizabeth Oval Bendigo LOCAL DERBY GAME VENUE Ovens & King DFL v Hume FL Howlong FC NO DOGS OR ALCOHOL ALLOWED TO BE BROUGHT INTO THE GROUNDS TRFM Gippsland League v Murray Football League 1 AFL VICTORIA WELCOME WELCOME TO THE 2018 WORKSAFE AFL VICTORIA COMMUNITY CHAMPIONSHIPS The battle for the ultimate football bragging Kilda and Collingwood on Saturday night. -

Bringing Them Home 20 Years On: an Action Plan for Healing Bringing Them Home 20 Years On: an Action Plan for Healing

Bringing Them Home 20 years on: an action plan for healing Bringing Them Home 20 years on: an action plan for healing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healing Foundation Contents Executive summary 4 Background 6 The Stolen Generations 7 The Bringing Them Home report 10 Responding to Bringing Them Home 14 Why action is needed now 19 An action plan for making things right 26 Action one: comprehensive response for Stolen Generations members 27 Action two: healing intergenerational trauma 40 Action three: creating an environment for change 45 Appendix 1: key themes and recommendations from the Bringing Them Home report 50 Bibliography 52 We acknowledge Stolen Generations members across Australia, including those who have passed on, for their courage in sharing their stories and wisdom in the Bringing Them Home report. Notes 54 This report, written by Pat Anderson and Edward Tilton, was guided by the Healing Foundation’s Stolen Generations Reference Committee. The Committee’s efforts were central to ensuring that this report reflects the experience of Stolen Generations and for forming the critical recommendations to bring about change in Australia. We acknowledge and thank all other contributors who were consulted for this report. 1 …the past is very much with us today, in the continuing devastation of the lives of Indigenous Australians. That devastation cannot be addressed unless the whole community listens with an open heart and mind to the stories of what has happened in the past and, having listened and understood, commits itself to reconciliation. Extract from the 1997 Bringing Them Home report 2 Executive summary On 26 May 1997 the landmark Bringing Them Home report was tabled in Federal While this report might primarily detail the response from government to the Parliament. -

Contributing Authors

Contributing Authors Tom Calma Dr Tom Calma is an Aboriginal elder from the Kungarakan tribal group and a member of the Iwaidja tribal group in the Northern Territory. He has been involved in Aboriginal affairs at a local, community, state, national and international level focusing on rural and remote Australia, health, education and economic development. Dr Calma was appointed National Coordinator, Tackling Indigenous Smoking in March 2010 to lead the fight against tobacco use in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Past positions include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner and Race Discrimination Commissioner at the Australian Human Rights Commission, and senior Australian diplomat in India and Vietnam. Through his 2005 Social Justice Report, Dr Calma called for the life expectancy gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people to be closed within a generation and laid the groundwork for the Close the Gap campaign. He chaired the Close the Gap Campaign Steering Committee for Indigenous Health Equality since its inception in March 2006 that has effectively brought national attention to achieving health equality for Indigenous peoples by 2030. He is a strong advocate for Indigenous rights and empowerment, and has spearheaded initiatives including the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples, development of the inaugural Indigenous suicide prevention strategy and justice reinvestment. In 2007, Dr Calma was named by the Bulletin Magazine as the Most Influential Indigenous Person in Australia and in 2008 was named GQ Magazine’s 2008 Man of Inspiration for his work in Indigenous Affairs. In 2010, he was awarded an honorary doctor of letters from Charles Darwin University and named by Australian Doctor Magazine as one of the 50 Most Influential People in medicine in Australia.