MYLES RUSSELL-COOK William Barak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graphic Encounters Conference Program

Meeting with Malgana people at Cape Peron, by Jacque Arago, who wrote, ‘the watched us as dangerous enemies, and were continually pointing to the ship, exclaiming, ayerkade, ayerkade (go away, go away)’. Graphic Encounters 7 Nov – 9 Nov 2018 Proudly presented by: LaTrobe University Centre for the Study of the Inland Program Melbourne University Forum Theatre Level 1 Arts West North Wing 153 148 Royal Parade Parkville Wednesday 7 November Program 09:30am Registrations 10:00am Welcome to Country by Aunty Joy Murphy Wandin AO 10:30am (dis)Regarding the Savages: a short history of published images of Tasmanian Aborigines Greg Lehman 11.30am Morning Tea 12.15pm ‘Aborigines of Australia under Civilization’, as seen in Colonial Australian Illustrated Newspapers: Reflections on an article written twenty years ago Peter Dowling News from the Colonies: Representations of Indigenous Australians in 19th century English illustrated magazines Vince Alessi Valuing the visual: the colonial print in a pseudoscientific British collection Mary McMahon 1.45pm Lunch 2.45pm Unsettling landscapes by Julie Gough Catherine De Lorenzo and Catherine Speck The 1818 Project: Reimagining Joseph Lycett’s colonial paintings in the 21st century Sarah Johnson Printmaking in a Post-Truth World: The Aboriginal Print Workshops of Cicada Press Michael Kempson 4.15pm Afternoon tea and close for day 1 2 Thursday 8 November Program 10:00am Australian Blind Spots: Understanding Images of Frontier Conflict Jane Lydon 11:00 Morning Tea 11:45am Ad Vivum: a way of being. Robert Neill -

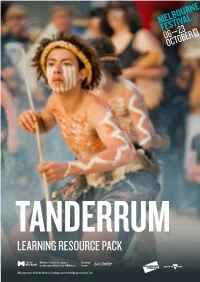

Learning Resource Pack

TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK Melbourne Festival’s free program Presenting proudly supported by the City of Melbourne Partner With support from VicHealth, Newsboys Foundation and the Helen Macpherson Smith Trust TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK INTRODUCTION STATEMENT FROM ILBIJERRI THEATRE COMPANY Welcome to the study guide of the 2016 Melbourne Festival production of ILBIJERRI (pronounced ‘il BIDGE er ree’) is a Woiwurrung word meaning Tanderrum. The activities included are related to the AusVELS domains ‘Coming Together for Ceremony’. as outlined below. These activities are sequential and teachers are ILBIJERRI is Australia’s leading and longest running Aboriginal and encouraged to modify them to suit their own curriculum planning and Torres Strait Islander Theatre Company. the level of their students. Lesson suggestions for teachers are given We create challenging and inspiring theatre creatively controlled by within each activity and teachers are encouraged to extend and build on Indigenous artists. Our stories are provocative and affecting and give the stimulus provided as they see fit. voice to our unique and diverse cultures. ILBIJERRI tours its work to major cities, regional and remote locations AUSVELS LINKS TO CURRICULUM across Australia, as well as internationally. We have commissioned 35 • Cross Curriculum Priorities: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander new Indigenous works and performed for more than 250,000 people. History and Cultures We deliver an extensive program of artist development for new and • The Arts: Creating and making, Exploring and responding emerging Indigenous writers, actors, directors and creatives. • Civics and Citizenship: Civic knowledge and Born from community, ILBIJERRI is a spearhead for the Australian understanding, Community engagement Indigenous community in telling the stories of what it means to be Indigenous in Australia today from an Indigenous perspective. -

Land Hunger: Port Phillip, 1835

Land Hunger: Port Phillip, 1835 By Glen Foster An historical game using role-play and cards for 4 players from upper Primary school to adults. © Glen Foster, 2019 1 Published by Port Fairy Historical Society 30 Gipps Street, Port Fairy. 3284. Telephone: (03) 5568 2263 Email: [email protected] Postal address: Port Fairy Historical Society P.O. Box 152, Port Fairy, Victoria, 3284 Australia Copyright © Glen Foster, 2019 Reproduction and communication for educational and private purposes Educational institutions downloading this work are able to photocopy the material for their own educational purposes. The general public downloading this work are able to photocopy the material for their own private use. Requests and enquiries for further authorisation should be addressed to Glen Foster: email: [email protected]. Disclaimers These materials are intended for education and training and private use only. The author and Port Fairy Historical Society accept no responsibility or liability for any incomplete or inaccurate information presented within these materials within the poetic license used by the author. Neither the author nor Port Fairy Historical Society accept liability or responsibility for any loss or damage whatsoever suffered as a result of direct or indirect use or application of this material. Print on front page shows members of the Kulin Nations negotiating a “treaty” with John Batman in 1835. Reproduced courtesy of National Library of Australia. George Rossi Ashton, artist. © Glen Foster, 2019 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION -

William Barak

WILLIAM BARAK A brief essay about William Barak drawn from the booklet William Barak - Bridge Builder of the Kulin by Gibb Wettenhall, and published by Aboriginal Affairs Victoria. Barak was educated at the Yarra Mission School in Narrm (Melbourne), and was a tracker in the Native Police before, as his father had done, becoming ngurungaeta (clan leader). Known as energetic, charismatic and mild mannered, he spent much of his life at Coranderrk Reserve, a self-sufficient Aboriginal farming community in Healesville. Barak campaigned to protect Coranderrk, worked to improve cross-cultural understanding and created many unique artworks and artefacts, leaving a rich cultural legacy for future generations. Leader William Barak was born into the Wurundjeri clan of the Woi wurung people in 1823, in the area now known as Croydon, in Melbourne. Originally named Beruk Barak, he adopted the name William after joining the Native Police as a 19 year old. Leadership was in Barak's blood: his father Bebejan was a ngurunggaeta (clan head) and his Uncle Billibellary, a signatory to John Batman's 1835 "treaty", became the Narrm (Melbourne) region's most senior elder. As a boy, Barak witnessed the signing of this document, which was to have grave and profound consequences for his people. Soon after white settlement a farming boom forced the Kulin peoples from their land, and many died of starvation and disease. During those hard years, Barak emerged as a politically savvy leader, skilled mediator and spokesman for his people. In partnership with his cousin Simon Wonga, a ngurunggaeta, Barak worked to establish and protect Coranderrk, a self- sufficient Aboriginal farming community in Healesville, and became a prominent figure in the struggle for Aboriginal rights and justice. -

Billibellary's

Billibellary’s Walk A cultural interpretation of the landscape that provides an experience of connection to country which Wurundjeri people continue to have, both physically and spiritually. Lying within the University of Melbourne’s built environment are the whispers and songs of the Wurundjeri people. As one of the clans of the Kulin Nation, the Wurundjeri people of the Woiwurrung language group walked the grounds upon which the University now stands for more than 40,000 years Stop 4 – Aboriginal Knowledge Stop 10 – Billibellary’s Country Aboriginal knowledge, bestowed through an oral tradition, is What would Billibellary think if he were to walk with you ever-evolving, enabling it to reflect its context. Sir Walter Baldwin now? The landscape has changed but while it looks Spencer, the University’s foundation professor of Biology in 1887, different on the surface Billibellary might remind you it still was highly esteemed for his anthropological and ethnographic holds the story of the Wurundjeri connection to Country work in Aboriginal communities but the Aboriginal community and our continuing traditions. today regards this work as a misappropriation of Aboriginal culture and knowledge. Artist: Kelly Koumalatsos, Wergaia/Wemba Wemba, Stop 5 – Self-determination and Community Control Possum Skin Cloak, Koorie Heritage Trust collection. Murrup Barak, Melbourne Indigenous Development Institute represents the fight that Billibellary, the Wurundjeri people, and Take a walk through Billibellary’s Country. indeed the whole Kulin nation were to face. The institute’s name Feel, know, imagine Melbourne’s six uses Woiwurung language to speak of the spirit of William Barak, seasons as they are subtly reconstructed Billibellary’s nephew and successor as Ngurungaeta to the as the context for understanding place and Wurundjeri Willam. -

Victorian Honour Roll of Women

INSPIRATIONAL WOMEN FROM ALL WALKS OF LIFE OF WALKS ALL FROM WOMEN INSPIRATIONAL VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 PAGE I VICTORIAN HONOUR To receive this publication in an accessible format phone 03 9096 1838 ROLL OF WOMEN using the National Relay Service 13 36 77 if required, or email Women’s Leadership [email protected] Authorised and published by the Victorian Government, 1 Treasury Place, Melbourne. © State of Victoria, Department of Health and Human Services March, 2018. Except where otherwise indicated, the images in this publication show models and illustrative settings only, and do not necessarily depict actual services, facilities or recipients of services. This publication may contain images of deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Where the term ‘Aboriginal’ is used it refers to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Indigenous/Koori/Koorie is retained when it is part of the title of a report, program or quotation. ISSN 2209-1122 (print) ISSN 2209-1130 (online) PAGE II PAGE Information about the Victorian Honour Roll of Women is available at the Women Victoria website https://www.vic.gov.au/women.html Printed by Waratah Group, Melbourne (1801032) VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 2018 WOMEN OF ROLL HONOUR VICTORIAN VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 PAGE 1 VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 PAGE 2 CONTENTS THE 4 THE MINISTER’S FOREWORD 6 THE GOVERNOR’S FOREWORD 9 2O18 VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN INDUCTEES 10 HER EXCELLENCY THE HONOURABLE LINDA DESSAU AC 11 DR MARIA DUDYCZ -

Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Yurlendj-Nganjin

Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Yurlendj-nganjin Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Yurlendj-nganjin Edited by David Jones and Darryl Low Choy Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Yurlendj-nganjin Edited by David Jones and Darryl Low Choy This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by David Jones, Darryl Low Choy and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-7017-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-7017-7 Cover Image: Three Dreaming Trails that incorporate culture, language and ceremony and how they are connected to Country. Author: Mandy Nicholson Other photos: Donna Edwards We wish to respectfully acknowledge the Elders, families and forebears of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples from around Australia, past, present and future, who are and continue to be the Traditional Owners and custodians of these lands, waters and skies for many centuries, and in particular members of the Kaurna, Wadawurrung, Wurundjeri, Gunditjmara, Yuin, Wiradjuri, Wakka Wakka, Bidjara, Kuku Yalanji, Yawuru, Noongar/Nyungar, Quandamooka and Boon Wurrung Peoples who were passionate in seeking the fruition of this publication to provide a voice to their values. Yurlendj-nganjin (‘everyone's knowledge’ / ‘our intelligence’) Wumen-dji-ka bagungga-nganjin lalal ba gugung-bulok ba kirrip nugel- dhan ba kirrip-nganjinu Torres Strait-al Bawal-u, ba kyinandoo biik durn- durn-bulok, Wurundjeri biik-dui. -

Possum Skin Pedagogy: a Guide for Early Childhood Practitioners

Possum Skin Pedagogy: A Guide for Early Childhood Practitioners ‘Women Drumming’ by Annette Sax, Taungurung artist. This image reflects a special ceremony on Taungurung Country. Women are beating on their Walert Walert (possum skin drums). Sue Atkinson © 2017 Sue Atkinson The copyright of this document is owned by Sue Atkinson or in the case of some materials, by third parties. Sue Atkinson is happy for any and all of this paper to be distributed for information and study purposes, provided that any such distribution attributes its origin to Sue Atkinson and any third parties where relevant. Produced with the assistance of Action on Aboriginal Perspectives in Early Childhood and fka Children's Services, Melbourne. This document was proudly funded by the Warrawong Foundation. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this document contains the names of people who have passed on. Acknowledgements We acknowledge the Aboriginal people of Victoria as the traditional custodians of the lands and rivers on which this document was written. This document is inspired by the voices of Elders past, guided by the voices of Elders present and aims to strengthen the voices of Aboriginal children as future Elders. In this we honour and acknowledge Aboriginal Elders past, present and future. Sue Atkinson and the Action on Aboriginal Perspectives in Early Childhood Possum Skin Pedagogy subcommittee, Annette Sax, Mindy Blaise, Melodie Davies, Sandra Dean, Denise Rundle, Kylie McLennan, Brinda Mootoosamy and Maree Sheehan would like to thank the following Elders and other respected Aboriginal community leaders who contributed their knowledge to this project; The Late Uncle David Tournier (Narrindjerri, Yorta Yorta and Wathaurong), Aunty Fay Stewart Muir (B.A Education) Boonwurrung and Wemba Wemba, Uncle Colin Hunter Jnr Wurundjeri, Dr Aunty Doris Paton (PhD Education) Ngarigo Monero and Gunai, Vicki Couzens (M.A Education) Keeray Wooroong/Gunditjmara, Lee Darroch (BSW) Yorta Yorta, Annette Sax (Taungurung) and Mandy Nicholson (BA. -

Thematic Environmental History Aboriginal History

THEMATIC ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY ABORIGINAL HISTORY Prepared for City of Greater Bendigo FINAL REPORT June 2013 Adopted by City of Greater Bendigo Council July 31, 2013 Table of Contents Greater Bendigo’s original inhabitants 2 Introduction 2 Clans and country 2 Aboriginal life on the plains and in the forests 3 Food 4 Water 4 Warmth 5 Shelter 6 Resources of the plains and forests 6 Timber 6 Stone 8 The daily toolkit 11 Interaction between peoples: trade, marriage and warfare 12 British colonisation 12 Impacts of squatting on Aboriginal people 13 Aboriginal people on the goldfields 14 Aboriginal Protectorates 14 Aboriginal Reserves 15 Fighting for Identity 16 Authors/contributors The authors of this history are: Lovell Chen: Emma Hewitt, Dr Conrad Hamann, Anita Brady Dr Robyn Ballinger Dr Colin Pardoe LOVELL CHEN 2013 1 Greater Bendigo’s original inhabitants Introduction An account of the daily lives of the area’s Aboriginal peoples prior to European contact was written during the research for the Greater Bendigo Thematic Environmental History to achieve some understanding of life before European settlement, and to assist with tracing later patterns and changes. The repercussions of colonialism impacted beyond the Greater Bendigo area and it was necessary to extend the account of this area’s Aboriginal peoples to a Victorian context, including to trace movement and resettlement beyond this region. This Aboriginal history was drawn from historical records which include the observations of the first Europeans in the area, who documented what they saw in writing and sketches. Europeans brought their own cultural perceptions, interpretations and understandings to the documentation of Aboriginal life, and the stories recorded were not those of the Aboriginal people themselves. -

Koorie Perspectives in Curriculum Bulletin: December 2020

Koorie Perspectives in Curriculum Bulletin: December 2020 In this Bulletin, you’ll find Victorian Curriculum This edition of the Koorie links to Content Descriptions. Select the code Perspectives in Curriculum Bulletin and it will take you directly to the Victorian features: Curriculum site with additional elaborations. − Eureka Day & Koories on the Our Bulletins are interactive, and images and goldfields links will take you to a host of accessible online resources, audio-visual and print. − Ebenezer Mission handover anniversary We know that Aboriginal people are the best − World Human Rights Day equipped and the most appropriate people to − First Native Title settlement win in teach Indigenous knowledge. Therefore, wherever possible you should seek to involve Victoria your local Koorie community in education − Xmas Eve, the Wathaurung & programs that involve Aboriginal perspectives. escapee convict William Buckley For some guidance about working with your − A Christmas Letter local Koorie community to enrich your − Tune into the Arts: Live, online teaching program, see VAEAI’s Protocols for and in the news Koorie Education in Primary and Secondary Schools. Focused on Aboriginal Histories and Cultures, the aim of the Koorie Perspectives Bulletin is to For a summary of key Learning Areas and highlight Victorian Koorie voices, stories, Content Descriptions directly related to achievements, leadership and connections; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and suggest a range of activities and resources and cultures within the Victorian Curriculum F- around key dates for starters. Of course any of 10, select the pelican or link for a copy of the these topics can be taught throughout the VCAA’s: Learning about Aboriginal and Torres school year and we encourage you to use these Strait Islander histories and cultures. -

Looking Glass: a Virtual Celebration Sunday 20 December, 4-5Pm a Special Online Event, Free, Register at Twma.Com.Au

9 December 2020 Looking Glass: A Virtual Celebration Sunday 20 December, 4-5pm A special online event, free, register at twma.com.au Ella Havelka with Yhonnie Scarce’s Cloud Chamber 2020, installation view, Looking Glass: Judy Watson and Yhonnie Scarce. Photo: Sean Fennessy. Courtesy of the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne. Featuring: • Welcome to Country and Smoking Ceremony by Senior Wurundjeri Elder, Aunty Joy Murphy Wandin AO • A conversation between Looking Glass curator Hetti Perkins and artists Judy Watson and Yhonnie Scarce, moderated by Victoria Lynn, Director, TarraWarra Museum of Art • The premiere of Fragmented, choreographed and performed by Wiradjuri woman Ella Havelka. In celebration of its current exhibition Looking Glass: Judy Watson and Yhonnie Scarce, TarraWarra Museum of Art will hold a special online event on Sunday 20 December from 4-5pm. Looking Glass: A Virtual Celebration will invite audiences from across the country to experience a moving Welcome to Country and Smoking Ceremony by Senior Wurundjeri Elder, Aunty Joy Murphy Wandin AO, hear from exhibition curator Hetti Perkins and artists Judy Watson and Yhonnie Scarce in a live panel discussion moderated by Museum Director, Victoria Lynn, followed by a powerful dance performance by Ella Havelka. Wiradjuri woman Ella Havelka will premiere her new work Fragmented, developed for and inspired by the Looking Glass exhibition, with an original score composed by Eric Avery and Ronald Smith. 9 December 2020 Havelka, an Australian Ballet and Bangarra alumni, said of her new dance work, “I’ve drawn inspiration from Looking Glass by creating a dance piece that expresses the ways in which trauma can cause continual knock-on effects; the power of resilience and resistance; the healing that is only effective after time has passed and when cycles are renewed and, finally, the importance of returning to Country." Victoria Lynn, Director, TarraWarra Museum of Art, said the event would provide a wonderful insight into Looking Glass and contemporary Indigenous understanding. -

William Barak Australia’S Leading Civil Rights Figure of the 19Th Century

William Barak Australia’s leading civil rights figure of the 19th Century William Barak was born at Brushy Creek in present day Wonga Park in 1823. It was named after his cousin Simon Wonga who preceded Barak as Ngurungaeta (Headman, pronounced ung-uh-rung-eye-tuh) of the Wurundjeri. Both Wonga and Barak had been present as 13 and 11 year olds in 1835 when John Batman met tribal Elders on the Plenty River. Batman claimed he was purchasing their land, but to the Wurundjeri it was a Tanderum Ceremony, inviting white people to share the bounty and stewardship of the land. Apart from having been decimated by the smallpox holocausts of 1789 and 1828, the motivation for offering to share the land was that the escaped convict William Buckley had warned them for many years that white men would come with terrible weapons and take the land. The Wurundjeri were soon to be massively disappointed when the incoming stream of white people showed a complete ignorance on any principles of ecological management, and brought even more diseases. Within a decade the Wurundjeri were driven from their lands and prevented from conducting annual burning off to regenerate food sources and prevent bushfires. The remnants of the Wurundjeri were forced to either live in poverty on the urban fringes, or in camps along the Yarra such as at Bolin-Bolin Billabong and Pound Bend in Warrandyte. Both Barak and Wonga meanwhile set about gaining an education in the ways of the white man with Barak attending the government’s Yarra Mission School from 1837 to 1839, then joining the Native Mounted Police in 1844.