FIRST CONTACT in PORT PHILLIP Within This Section, Events Are Discussed Relating to the Colonisation of Port Phillip in 1835

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AUG 2008 Wurundjeri RAP Appointment Decision Pdf 43.32 KB

DECISION OF THE VICTORIAN ABORIGINAL HERITAGE COUNCIL IN RELATION TO AN APPLICATION BY WURUNDJERI TRIBE LAND AND COMPENSATION CULTURAL HERITAGE COUNCIL INC TO BE A REGISTERED ABORIGINAL PARTY DATE OF DECISION: 22 AUGUST 2008 Decision The Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council (“the Council”) registers the Wurundjeri Tribe Land and Compensation Cultural Heritage Council Inc (“Wurundjeri Inc”) as a registered Aboriginal party (“RAP”) over part of its application area. A map showing the area for which Wurundjeri Inc has been made a RAP (“the RAP Area”) is attached (Attachment 1). The Council is still considering the remaining area for which Wurundjeri Inc has sought to be a RAP. Reasons for Decision The Council accepts that Wurundjeri Inc is an organisation that represents the Traditional Owners of the RAP Area. The members of Wurundjeri Inc are all descendants of a Woiwurrung / Wurundjeri man Bebejan, through his daughter Annie Borate (Boorat), and in turn, her son Robert Wandin (Wandoon). Bebejan was Ngurungaeta (headman) of the Wurundjeri people and was present at John Batman’s ‘treaty’ signing in 1835. Wurundjeri Inc was incorporated in 1985 and has had a long history of managing and protecting cultural heritage in its application area on behalf of Woiwurrung people. The Council was satisfied Wurundjeri Inc is capable of carrying out the functions of a RAP. RAP applications have also been made by other Traditional Owner groups in the vicinity of (and in some cases overlapping with) the Wurundjeri RAP application area. These include the Wathaurung/ Wathaurong people to the west, the Dja Dja Wurrung/ Jaara Jaara people to the north-west, the Taungurung people to the north, the Gunai/Kurnai people to the east and the Boon Wurrung/ Bunurong people to the south. -

Melbourne-Dreaming-Intro 1.Pdf (Pdf, 1.91

ABOUT THIS BOOK Melbourne Dreaming is both a guide book and social history of Melbourne, and the events and cultural traditions that have shaped local Aboriginal people’s lives. It aims to show where to look to gain a better understanding of the rich heritage and complex culture of Aboriginal people in Melbourne both before and since colonisation. It was first published in 1997. This is a completely updated and expanded edition. Melbourne Dreaming provides practical information on visiting both historical and contemporary sites located in the city centre, surrounding suburbs and outer areas. Arranged into seven precincts, Melbourne Dreaming takes you to beaches, parklands, camping places, historical sites, exhibitions, cultural displays and buildings. For Melbourne’s Aboriginal people the landscape prior to European settlement over which we travel was the face of the divine — the imprint of the ancestral creation beings that shaped the landscape on their epic journeys. Exploring Melbourne’s Aboriginal places is a way of paying respect to this sacred tradition while learning more about our shared and ancient history. Sites include locations and traces of important places before European settlement in 1835 such as shell middens, scarred trees, wells, fish traps, mounds and quarries. Other sites describe critical events that occurred because of the impact of European settlement. More recent places are the focus of contemporary life. What these places share in common is that each illustrates an important part of the overall story of the first inhabitants, the Kulin. Stories and photographs of some places of interest which have restricted access or cannot be visited have also been included. -

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 87, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2016 ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Royal Historical Society of Victoria is a community organisation comprising people from many fields committed to collecting, researching and sharing an understanding of the history of Victoria. The Victorian Historical Journal is a fully refereed journal dedicated to Australian, and especially Victorian, history produced twice yearly by the Publications Committee, Royal Historical Society of Victoria. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Jill Barnard Marilyn Bowler Richard Broome (Convenor) Marie Clark Mimi Colligan Don Garden (President, RHSV) Don Gibb David Harris (Editor, Victorian Historical Journal) Kate Prinsley Marian Quartly (Editor, History News) John Rickard Judith Smart (Review Editor) Chips Sowerwine Carole Woods BECOME A MEMBER Membership of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria is open. All those with an interest in history are welcome to join. Subscriptions can be purchased at: Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Journals are also available for purchase online: www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ISSUE 286 VOLUME 87, NUMBER 2 DECEMBER 2016 Royal Historical Society of Victoria Victorian Historical Journal Published by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Fax: 03 9326 9477 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Copyright © the authors and the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 2016 All material appearing in this publication is copyright and cannot be reproduced without the written permission of the publisher and the relevant author. -

Expedtion from Van Diemen's Land to Port Phillip in 1835

(No. 44.) 1885. PARLIAMENT OF TASMANIA. EXPEDI'TION FROM VAN DIEMEN'S LAND TO PORT PHILLIP IN 1835. Presented to both Houses ot Parliament by l-t is Excellency's Command. EXPEDITION FROM VAN DIEMEN'S LAND TO PORT PHILLIP, 1835 ■ Hobart Town, 25tl1 June, 1835. Srn, ' I HAVE the honor of reporting to Your Excellency, for the information of His Majesty's Government, the result of an Expedition undertaken by myself, at the expense and in conjunC'tion with several gentlemen, inhabitants of Van Diemen's Land, to Port Phillip, on the south-western point of New Holland, for the purpose of forming an extensive Pastoral Establishment, and combining therewith the civilization of the Native Tribes who are living in that part of the country. Before I enter into the details I deem it necessary to state, for the information of His Majesty's Government, that I am a native of New South Wales, and that for the last six years I have been most actively employed in endeavoring to civilize the Aboriginal Natives of Van Diemen's Land, and in order to enable the local Government of this Colony to carry that important object into full effect, I procured from New South Wales eleven aboriginal Natives of New Holland, who were, under my guidance, mainly instrumental in carrying into effect the humane objects of this Government · towards the Aborigines of this Island. I also deem it necessary to state that I have been for many years impressed with the opinion that a most advantag·eous Settlement might be formed at Western Port, or Port Phillip, and that, in 1827, Mr. -

Your Candidates Metropolitan

YOUR CANDIDATES METROPOLITAN First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria Election 2019 “TREATY TO ME IS A RECOGNITION THAT WE ARE THE FIRST INHABITANTS OF THIS COUNTRY AND THAT OUR VOICE BE HEARD AND RESPECTED” Uncle Archie Roach VOTING IS OPEN FROM 16 SEPTEMBER – 20 OCTOBER 2019 Treaties are our self-determining right. They can give us justice for the past and hope for the future. The First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria will be our voice as we work towards Treaties. The First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria will be set up this year, with its first meeting set to be held in December. The Assembly will be a powerful, independent and culturally strong organisation made up of 32 Victorian Traditional Owners. If you’re a Victorian Traditional Owner or an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person living in Victoria, you’re eligible to vote for your Assembly representatives through a historic election process. Your voice matters, your vote is crucial. HAVE YOU ENROLLED TO VOTE? To be able to vote, you’ll need to make sure you’re enrolled. This will only take you a few minutes. You can do this at the same time as voting, or before you vote. The Assembly election is completely Aboriginal owned and independent from any Government election (this includes the Victorian Electoral Commission and the Australian Electoral Commission). This means, even if you vote every year in other elections, you’ll still need to sign up to vote for your Assembly representatives. Don’t worry, your details will never be shared with Government, or any electoral commissions and you won’t get fined if you decide not to vote. -

1 Ron Clarke, Runner 1937- I Had the Great Honour of Carrying the Torch

1 PEOPLE WHO CHANGED MELBOURNE Schools City Tour of Melbourne: www.melbournewalks.com.au/city-schools-tour ; www.melbournewalks.com; [email protected] ; Copyright Melbourne Walks © Peter Lalor, Rebel (1827-1889) As Eureka stockade leader in December 1854 I took the oath of the rebel miners: ‘We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other to defend our rights and liberties’. I lost my arm in that battle yet later became the only outlaw ever elected to parliament! On 24 Nov 1857 all men received the right to vote. Our Southern Cross flag is now the Australian flag. Down with tyranny! John Batman, Founder of Colonial Melbourne (1801 –1839) I was a Tasmania sheep farmer when I led an expedition to sign a ‘treaty’ with Aboriginal ‘chiefs’ in 1835 to found the settlement of Melbourne and the colony of Victoria. I captured bushranger Mathew Brady and married a runaway convict Eliza Callaghan. We had seven children in all. At Melbourne’s first land sale in 1837. I bought the Young and Jackson Hotel site opposite Flinders Street Station to build a home for my children. It became a schoolhouse in 1839 and today a famous pub. See Chloe upstairs! Ron Clarke, Runner 1937- I had the great honour of carrying the torch into the stadium in the Melbourne Olympic Games in 1956. I was also the first man to run three miles in under 13 minutes. They said I was fastest man on the planet when I broke 17 world records and 25 Australian records in 1965. -

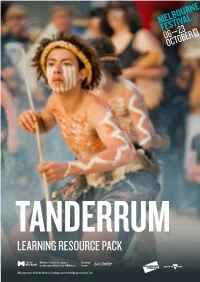

Learning Resource Pack

TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK Melbourne Festival’s free program Presenting proudly supported by the City of Melbourne Partner With support from VicHealth, Newsboys Foundation and the Helen Macpherson Smith Trust TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK INTRODUCTION STATEMENT FROM ILBIJERRI THEATRE COMPANY Welcome to the study guide of the 2016 Melbourne Festival production of ILBIJERRI (pronounced ‘il BIDGE er ree’) is a Woiwurrung word meaning Tanderrum. The activities included are related to the AusVELS domains ‘Coming Together for Ceremony’. as outlined below. These activities are sequential and teachers are ILBIJERRI is Australia’s leading and longest running Aboriginal and encouraged to modify them to suit their own curriculum planning and Torres Strait Islander Theatre Company. the level of their students. Lesson suggestions for teachers are given We create challenging and inspiring theatre creatively controlled by within each activity and teachers are encouraged to extend and build on Indigenous artists. Our stories are provocative and affecting and give the stimulus provided as they see fit. voice to our unique and diverse cultures. ILBIJERRI tours its work to major cities, regional and remote locations AUSVELS LINKS TO CURRICULUM across Australia, as well as internationally. We have commissioned 35 • Cross Curriculum Priorities: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander new Indigenous works and performed for more than 250,000 people. History and Cultures We deliver an extensive program of artist development for new and • The Arts: Creating and making, Exploring and responding emerging Indigenous writers, actors, directors and creatives. • Civics and Citizenship: Civic knowledge and Born from community, ILBIJERRI is a spearhead for the Australian understanding, Community engagement Indigenous community in telling the stories of what it means to be Indigenous in Australia today from an Indigenous perspective. -

Land Hunger: Port Phillip, 1835

Land Hunger: Port Phillip, 1835 By Glen Foster An historical game using role-play and cards for 4 players from upper Primary school to adults. © Glen Foster, 2019 1 Published by Port Fairy Historical Society 30 Gipps Street, Port Fairy. 3284. Telephone: (03) 5568 2263 Email: [email protected] Postal address: Port Fairy Historical Society P.O. Box 152, Port Fairy, Victoria, 3284 Australia Copyright © Glen Foster, 2019 Reproduction and communication for educational and private purposes Educational institutions downloading this work are able to photocopy the material for their own educational purposes. The general public downloading this work are able to photocopy the material for their own private use. Requests and enquiries for further authorisation should be addressed to Glen Foster: email: [email protected]. Disclaimers These materials are intended for education and training and private use only. The author and Port Fairy Historical Society accept no responsibility or liability for any incomplete or inaccurate information presented within these materials within the poetic license used by the author. Neither the author nor Port Fairy Historical Society accept liability or responsibility for any loss or damage whatsoever suffered as a result of direct or indirect use or application of this material. Print on front page shows members of the Kulin Nations negotiating a “treaty” with John Batman in 1835. Reproduced courtesy of National Library of Australia. George Rossi Ashton, artist. © Glen Foster, 2019 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION -

31. John Batman's Title Deeds Author(S): George Warner and J

31. John Batman's Title Deeds Author(s): George Warner and J. Edge-Partington Source: Man, Vol. 15 (1915), pp. 49-51 Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2787879 Accessed: 24-06-2016 17:04 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Man This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Fri, 24 Jun 2016 17:04:29 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms 1915.] MAN. [No. 31. ORIGINAL ARTICLES. With Plates D and E. Australia: Victoria. Warner-Edge-Partington. John Batman's Title Deeds. By Sir George Warner and J. Edge- 2 Partinglon. UI John Batman was born at Parramatta, Sydney, in 1800, and emigrated to Van Diemen's Land twenty years later, where be became a flourishing farmer. At this time considerable difficulty was beinag experienced with the natives, and the niame of John Batman stands out as a splendid example of humane treatment, in place of the "crow-shooting" adopted by many of the settlers and ex-convicts at that time. -

SL Magazine Summer Edition 2017-18

–Magazine for members Summer 2017–18 Painting by numbers: Ferdinand Bauer Message Dear readers, visitors and friends, What a privilege it is to be State Librarian, responsible for one of the best loved and most important institutions in Australia. Since I began on 28 August, I have encountered nothing but enthusiasm, good will and a broad desire to see the Library continue to flourish and grow — a tribute to the three State Librarians with whom I have worked over the years, Regina Sutton, Alex Byrne and Lucy Milne. I also pay tribute to a remarkable generation of recent curators and librarians, now retired, including the likes of Paul Brunton, Alan Davies and Elizabeth Ellis. This time next year the Library will be a very different place — with more of its unique treasures on public show than ever before thanks to a great partnership between the NSW Government and our benefactors led by Michael Crouch AC, who is driving a major development of new galleries in the Mitchell wing, and John B Fairfax AO, who is behind a new learning centre being created in the same building. You can find a little more about the plans for the next phase of the Library’s history inside these pages, but I would like to mention a special event in November which draws attention to another very important aspect of the Library’s work — collaboration with scholars and scientists. For some years, the Belalberi Foundation (led by Peter Crossing AM and Sally Crossing AM) has generously supported original research into Australian natural history at the Library, and on 16 November we are launching a book and special online exhibition marking the culmination of this remarkable, long term project. -

William Barak

WILLIAM BARAK A brief essay about William Barak drawn from the booklet William Barak - Bridge Builder of the Kulin by Gibb Wettenhall, and published by Aboriginal Affairs Victoria. Barak was educated at the Yarra Mission School in Narrm (Melbourne), and was a tracker in the Native Police before, as his father had done, becoming ngurungaeta (clan leader). Known as energetic, charismatic and mild mannered, he spent much of his life at Coranderrk Reserve, a self-sufficient Aboriginal farming community in Healesville. Barak campaigned to protect Coranderrk, worked to improve cross-cultural understanding and created many unique artworks and artefacts, leaving a rich cultural legacy for future generations. Leader William Barak was born into the Wurundjeri clan of the Woi wurung people in 1823, in the area now known as Croydon, in Melbourne. Originally named Beruk Barak, he adopted the name William after joining the Native Police as a 19 year old. Leadership was in Barak's blood: his father Bebejan was a ngurunggaeta (clan head) and his Uncle Billibellary, a signatory to John Batman's 1835 "treaty", became the Narrm (Melbourne) region's most senior elder. As a boy, Barak witnessed the signing of this document, which was to have grave and profound consequences for his people. Soon after white settlement a farming boom forced the Kulin peoples from their land, and many died of starvation and disease. During those hard years, Barak emerged as a politically savvy leader, skilled mediator and spokesman for his people. In partnership with his cousin Simon Wonga, a ngurunggaeta, Barak worked to establish and protect Coranderrk, a self- sufficient Aboriginal farming community in Healesville, and became a prominent figure in the struggle for Aboriginal rights and justice. -

Billibellary's

Billibellary’s Walk A cultural interpretation of the landscape that provides an experience of connection to country which Wurundjeri people continue to have, both physically and spiritually. Lying within the University of Melbourne’s built environment are the whispers and songs of the Wurundjeri people. As one of the clans of the Kulin Nation, the Wurundjeri people of the Woiwurrung language group walked the grounds upon which the University now stands for more than 40,000 years Stop 4 – Aboriginal Knowledge Stop 10 – Billibellary’s Country Aboriginal knowledge, bestowed through an oral tradition, is What would Billibellary think if he were to walk with you ever-evolving, enabling it to reflect its context. Sir Walter Baldwin now? The landscape has changed but while it looks Spencer, the University’s foundation professor of Biology in 1887, different on the surface Billibellary might remind you it still was highly esteemed for his anthropological and ethnographic holds the story of the Wurundjeri connection to Country work in Aboriginal communities but the Aboriginal community and our continuing traditions. today regards this work as a misappropriation of Aboriginal culture and knowledge. Artist: Kelly Koumalatsos, Wergaia/Wemba Wemba, Stop 5 – Self-determination and Community Control Possum Skin Cloak, Koorie Heritage Trust collection. Murrup Barak, Melbourne Indigenous Development Institute represents the fight that Billibellary, the Wurundjeri people, and Take a walk through Billibellary’s Country. indeed the whole Kulin nation were to face. The institute’s name Feel, know, imagine Melbourne’s six uses Woiwurung language to speak of the spirit of William Barak, seasons as they are subtly reconstructed Billibellary’s nephew and successor as Ngurungaeta to the as the context for understanding place and Wurundjeri Willam.