Thematic Environmental History Aboriginal History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY and CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, 9 Fellows Road (Coombs Building), The Australian National University, Acton, ACT, 2601, or [email protected]. WARNING: Readers are notified that this publication may contain names or images of deceased persons. ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE UNCLE ROY PATTERSON AND JENNIFER JONES Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464066 ISBN (online): 9781760464073 WorldCat (print): 1224453432 WorldCat (online): 1224452874 DOI: 10.22459/OTL.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph: Patterson family photograph, circa 1904 This edition © 2020 ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. Contents Acknowledgements ....................................... vii Note on terminology ......................................ix Preface .................................................xi Introduction: Meeting and working with Uncle Roy ..............1 Part 1: Sharing Taungurung history 1. -

Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth-Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals

Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth-Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals Eva Bischoff Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series Series Editors Richard Drayton Department of History King’s College London London, UK Saul Dubow Magdalene College University of Cambridge Cambridge, UK The Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies series is a collection of studies on empires in world history and on the societies and cultures which emerged from colonialism. It includes both transnational, comparative and connective studies, and studies which address where particular regions or nations participate in global phenomena. While in the past the series focused on the British Empire and Commonwealth, in its current incarna- tion there is no imperial system, period of human history or part of the world which lies outside of its compass. While we particularly welcome the first monographs of young researchers, we also seek major studies by more senior scholars, and welcome collections of essays with a strong thematic focus. The series includes work on politics, economics, culture, literature, science, art, medicine, and war. Our aim is to collect the most exciting new scholarship on world history with an imperial theme. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/13937 Eva Bischoff Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth- Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals Eva Bischoff Department of International History Trier University Trier, Germany Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series ISBN 978-3-030-32666-1 ISBN 978-3-030-32667-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32667-8 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 This work is subject to copyright. -

Regional Development Victoria Regional Development Victoria

Regional Development victoRia Annual Report 12-13 RDV ANNUAL REPORT 12-13 CONTENTS PG1 CONTENTS Highlights 2012-13 _________________________________________________2 Introduction ______________________________________________________6 Chief Executive Foreword 6 Overview _________________________________________________________8 Responsibilities 8 Profile 9 Regional Policy Advisory Committee 11 Partners and Stakeholders 12 Operation of the Regional Policy Advisory Committee 14 Delivering the Regional Development Australia Initiative 15 Working with Regional Cities Victoria 16 Working with Rural Councils Victoria 17 Implementing the Regional Growth Fund 18 Regional Growth Fund: Delivering Major Infrastructure 20 Regional Growth Fund: Energy for the Regions 28 Regional Growth Fund: Supporting Local Initiatives 29 Regional Growth Fund: Latrobe Valley Industry and Infrastructure Fund 31 Regional Growth Fund: Other Key Initiatives 33 Disaster Recovery Support 34 Regional Economic Growth Project 36 Geelong Advancement Fund 37 Farmers’ Markets 37 Thinking Regional and Rural Guidelines 38 Hosting the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development 38 2013 Regional Victoria Living Expo 39 Good Move Regional Marketing Campaign 40 Future Priorities 2013-14 42 Finance ________________________________________________________ 44 RDV Grant Payments 45 Economic Infrastructure 63 Output Targets and Performance 69 Revenue and Expenses 70 Financial Performance 71 Compliance 71 Legislation 71 Front and back cover image shows the new $52.6 million Regional and Community Health Hub (REACH) at Deakin University’s Waurn Ponds campus in Geelong. Contact Information _______________________________________________72 RDV ANNUAL REPORT 12-13 RDV ANNUAL REPORT 12-13 HIGHLIGHTS PG2 HIGHLIGHTS PG3 September 2012 December 2012 > Announced the date for the 2013 Regional > Supported the $46.9 million Victoria Living Expo at the Good Move redevelopment of central Wodonga with campaign stand at the Royal Melbourne $3 million from the Regional Growth Show. -

Annual Report 2020 Five Years of Growth 2 WESTERN VICTORIA PRIMARY HEALTH NETWORK

Annual Report 2020 Five years of growth 2 WESTERN VICTORIA PRIMARY HEALTH NETWORK Contents About this Report . 3 Who We Are . 4 Report from the Chair . 6 Report from the Chief Executive Officer . 7 Financial Summary . .. 8 Strategic Plan 2017-2020 . 10 COVID-19 Changing the way we work . 14 Our Board . 16 Our Executive . 17 Organisation Chart . 17 Clinical and Community Advisory Councils . 18 3 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 About this report The Western Victoria Primary Health Network (WVPHN) Annual Report 2020 provides an overview of our activities and performance from July 1, 2019 to June 30, 2020. This report provides details on our services, how we have performed and information on the people who have worked with us and for us. This report was presented at the WVPHN Annual General Meeting on 29 October 2020. Theme of this report We welcome your feedback WVPHN has been operating for five Feedback is important to us and years – established 1 July 2015 . contributes to improving future reports for our readers . We welcome The design of this report depicts five your comments about this annual stylised growth lines, similar to growth report and ask you to forward them to rings in a tree . communications@westvicphn .com .au It also represents the organisation as The Annual Report 2020 is available being part of the health care landscape, online and can be downloaded: deeply integrated in the region and https://www westvicphn. .com .au/about- continuing to grow . us/publications/annual-reports 4 WESTERN VICTORIA PRIMARY HEALTH NETWORK Who We Are Western Victoria WVPHN is one of 31 Primary Health Networks (PHNs) across Australia and one of six in Victoria. -

Position Description

Wathaurong Aboriginal Co-operative Ltd. POSITION DESCRIPTION Disability Support and Domestic Assistance Workers Position Details Manager Disability Services Coordinator Direct Reports Nil Hours Casual hours Monday – Sunday. Some overnight stays and shift hours Location Mackey Street, North Geelong, with frequent travel to the surrounding area. Organisation The name Wathaurong (Wadda-Wurrung) is a recognised tribe (community) which consisted of some 25 clans (family groups) that formed part of the Kulin Nation of Aboriginal people. The traditional boundaries of the Wathaurong people span the coastline from the Werribee River to Lorne peninsula and traverse inland in a north westerly direction towards Ballarat. The Wathaurong people have lived within these regions for more than 25,000 years. As custodians of the Wathaurong lands, we are committed to working together to provide a secure future for our community by upholding the dignity of our ancestors; respecting our Elders and instilling a sense of cultural pride and belonging for our children and children’s children. The Wathaurong Aboriginal Co-operative Ltd was formed by the community in 1978 and registered in 1980, to support the social, economic, and cultural development of Aboriginal people, particularly within the Geelong and surrounding areas. The Co-operative provides a range of services including; family and community services, support to young people, justice support services; cultural heritage services, and health services. From time to time the organisation also undertakes special projects and economic development opportunities. The Co-operative expanded to include a Community Controlled Health Service, which contributes toward addressing the inequality in health status of Aboriginal people. The Wathaurong Health Service supports the general wellbeing of Aboriginal people by providing holistic health care with clinical and primary care services as well as health promoting activities. -

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 90, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2019 ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Victorian Historical Journal has been published continuously by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria since 1911. It is a double-blind refereed journal issuing original and previously unpublished scholarly articles on Victorian history, or occasionally on Australian history where it illuminates Victorian history. It is published twice yearly by the Publications Committee; overseen by an Editorial Board; and indexed by Scopus and the Web of Science. It is available in digital and hard copy. https://www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal/. The Victorian Historical Journal is a part of RHSV membership: https://www. historyvictoria.org.au/membership/become-a-member/ EDITORS Richard Broome and Judith Smart EDITORIAL BOARD OF THE VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL Emeritus Professor Graeme Davison AO, FAHA, FASSA, FFAHA, Sir John Monash Distinguished Professor, Monash University (Chair) https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/graeme-davison Emeritus Professor Richard Broome, FAHA, FRHSV, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University and President of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria Co-editor Victorian Historical Journal https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/rlbroome Associate Professor Kat Ellinghaus, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kellinghaus Professor Katie Holmes, FASSA, Director, Centre for the Study of the Inland, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kbholmes Professor Emerita Marian Quartly, FFAHS, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/marian-quartly Professor Andrew May, Department of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne https://www.findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au/display/person13351 Emeritus Professor John Rickard, FAHA, FRHSV, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/john-rickard Hon. -

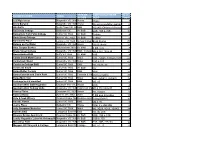

Strathbogie Shire Accommodation Audit

TYPE OF CONFIGURATION OF No of BUSINESS NAME TOWN ACCOM BEDS People 222 High Street Nagambie VIC 3608House House 7 48 on Barwon Nagambie VIC 3608House No accommodation available 0 Ain Garth Violet Town VIC 3669B&B 3Q/2KS/1Dfoldout/1Sfoldout 11 Bailieston Cottage Bailieston VIC Air B&B 2QB, 1DB & 3SB 10 Balmattum Park Farm Cottage Euroa VIC 3666 Air B&B Cottage 4 Bank Street Cottage Avenel VIC 3664 Air B&B Cottage 5 Bannisters Place Locksley Vic 3665 School Camp Bunk Rooms 70 Barong on the Water Nagambie VIC 3608House 3Q 6S (bunk) 12 Blue Tongue Berries Mitchelstown 3608 Air BNB 4 QS, sofa 8 Bryde Street Cottage Nagambie VIC 3608B&B / Cottage 2Q & 3S / 1Q & 2S 11 Boondaburra BnB Ruffy VIC 3666 Air B&B 1KB 4 Castle Creek Motel Euroa Euroa VIC 3666 Motel 7xQ, 7xQ&S, 1xQ&2S,1x3S 42 Centretown Motel Nagambie VIC 3608Motel 16Q & 10S 42 Courtside Cottage B&B Euroa VIC 3666 B&B 1Q, 1Sofa, 2S 6 Creekside B & B Euroa VIC 3666 Air B&B 1br 2 Euroa Butter Factory Euroa VIC 3666 B&B 6QB 12 Euroa Caravan and Cabin Park Euroa VIC 3666 Caravan & CabinVarious Park Cabins 38 Euroa Motor Inn Euroa VIC 3666 Motel 8xQ, 2xQ&1S, 2xQ&3S 32 Forlonge bed & breakfast Euroa VIC 3666 B&B 2Q, 2S 6 Goulburn Weir B&B Nagambie Goulburn Weir VIC 3608House 2QB 4 Goulburn Weir Holiday Units Nagambie VIC 3608Cabin/Unit Park4Q & 3S / 6D & 2S 36 Grassy Plains Graytown VIC 3608 House 1Q, 1Q&2S 6 Harvest Home Avenel VIC 3664 Hotel 7 QS plus 2 trundles 17 Hide & Seek Winery Kirwans Bridge, NagambieBoutique Accommodation3King/2Q/6KS 16 Holistic Haven Euroa VIC 3666 B&B 2Q & 1S -

Engaging Indigenous Communities

Engaging Indigenous Communities REGIONAL INDIGENOUS FACILITATOR INDIGENOUS PEOPLE’S GOALS AND The Port Phillip & Westernport CMA employs a Regional ASPIRATIONS Indigenous Facilitator funded through the Australian During 2014/15, a study was undertaken with Government’s National Landcare Programme. In Wurundjeri, Wathaurung, Wathaurong and Boon 2014/15, the facilitator arranged numerous events Wurrung people regarding their communities’ goals and and activities to improve the Indigenous cultural aspirations for involvement in land management and awareness and understanding of Board members and sustainable agriculture. The study improved the mutual staff from the Port Phillip & Westernport CMA and from understanding of priority activities for the future and various other organisations and community groups. set a basis for potential formal agreements between The facilitator also worked directly with Indigenous the Port Phillip & Westernport CMA and the Indigenous organisations and communities to document their goals organisations. relating to natural resource management and agriculture. A coordinated program of grants was established to help INDIGENOUS ENVIRONMENT GRANTS Indigenous organisations undertake on-ground projects and training to increase employment opportunities. In 2014/15, $75,000 of Indigenous environment grants were awarded as part of the Port Phillip & Westernport IMPROVING CULTURAL AWARENESS AND CMA’s project. This included grants to: UNDERSTANDING • Wathaurung Aboriginal Corporation to run 4 community, business and corporate -

Your Candidates Metropolitan

YOUR CANDIDATES METROPOLITAN First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria Election 2019 “TREATY TO ME IS A RECOGNITION THAT WE ARE THE FIRST INHABITANTS OF THIS COUNTRY AND THAT OUR VOICE BE HEARD AND RESPECTED” Uncle Archie Roach VOTING IS OPEN FROM 16 SEPTEMBER – 20 OCTOBER 2019 Treaties are our self-determining right. They can give us justice for the past and hope for the future. The First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria will be our voice as we work towards Treaties. The First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria will be set up this year, with its first meeting set to be held in December. The Assembly will be a powerful, independent and culturally strong organisation made up of 32 Victorian Traditional Owners. If you’re a Victorian Traditional Owner or an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person living in Victoria, you’re eligible to vote for your Assembly representatives through a historic election process. Your voice matters, your vote is crucial. HAVE YOU ENROLLED TO VOTE? To be able to vote, you’ll need to make sure you’re enrolled. This will only take you a few minutes. You can do this at the same time as voting, or before you vote. The Assembly election is completely Aboriginal owned and independent from any Government election (this includes the Victorian Electoral Commission and the Australian Electoral Commission). This means, even if you vote every year in other elections, you’ll still need to sign up to vote for your Assembly representatives. Don’t worry, your details will never be shared with Government, or any electoral commissions and you won’t get fined if you decide not to vote. -

Taylors Hill-Werribee South Sunbury-Gisborne Hurstbridge-Lilydale Wandin East-Cockatoo Pakenham-Mornington South West

TAYLORS HILL-WERRIBEE SOUTH SUNBURY-GISBORNE HURSTBRIDGE-LILYDALE WANDIN EAST-COCKATOO PAKENHAM-MORNINGTON SOUTH WEST Metro/Country Postcode Suburb Metro 3200 Frankston North Metro 3201 Carrum Downs Metro 3202 Heatherton Metro 3204 Bentleigh, McKinnon, Ormond Metro 3205 South Melbourne Metro 3206 Albert Park, Middle Park Metro 3207 Port Melbourne Country 3211 LiQle River Country 3212 Avalon, Lara, Point Wilson Country 3214 Corio, Norlane, North Shore Country 3215 Bell Park, Bell Post Hill, Drumcondra, Hamlyn Heights, North Geelong, Rippleside Country 3216 Belmont, Freshwater Creek, Grovedale, Highton, Marhsall, Mt Dunede, Wandana Heights, Waurn Ponds Country 3217 Deakin University - Geelong Country 3218 Geelong West, Herne Hill, Manifold Heights Country 3219 Breakwater, East Geelong, Newcomb, St Albans Park, Thomson, Whington Country 3220 Geelong, Newtown, South Geelong Anakie, Barrabool, Batesford, Bellarine, Ceres, Fyansford, Geelong MC, Gnarwarry, Grey River, KenneQ River, Lovely Banks, Moolap, Moorabool, Murgheboluc, Seperaon Creek, Country 3221 Staughtonvale, Stone Haven, Sugarloaf, Wallington, Wongarra, Wye River Country 3222 Clilon Springs, Curlewis, Drysdale, Mannerim, Marcus Hill Country 3223 Indented Head, Port Arlington, St Leonards Country 3224 Leopold Country 3225 Point Lonsdale, Queenscliffe, Swan Bay, Swan Island Country 3226 Ocean Grove Country 3227 Barwon Heads, Breamlea, Connewarre Country 3228 Bellbrae, Bells Beach, jan Juc, Torquay Country 3230 Anglesea Country 3231 Airleys Inlet, Big Hill, Eastern View, Fairhaven, Moggs -

Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony Economies of Dispossession Around the Pacific Rim

Cambridge Imperial & Post-Colonial Studies INTIMACIES OF VIOLENCE IN THE SETTLER COLONY ECONOMIES OF DISPOSSESSION AROUND THE PACIFIC RIM EDITED BY PENELOPE EDMONDS & AMANDA NETTELBECK Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series Series Editors Richard Drayton Department of History King’s College London London, UK Saul Dubow Magdalene College University of Cambridge Cambridge, UK The Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies series is a collection of studies on empires in world history and on the societies and cultures which emerged from colonialism. It includes both transnational, comparative and connective studies, and studies which address where particular regions or nations participate in global phenomena. While in the past the series focused on the British Empire and Commonwealth, in its current incarna- tion there is no imperial system, period of human history or part of the world which lies outside of its compass. While we particularly welcome the first monographs of young researchers, we also seek major studies by more senior scholars, and welcome collections of essays with a strong thematic focus. The series includes work on politics, economics, culture, literature, science, art, medicine, and war. Our aim is to collect the most exciting new scholarship on world history with an imperial theme. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/13937 Penelope Edmonds Amanda Nettelbeck Editors Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony Economies of Dispossession around the Pacific Rim Editors Penelope Edmonds Amanda Nettelbeck School of Humanities School of Humanities University of Tasmania University of Adelaide Hobart, TAS, Australia Adelaide, SA, Australia Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series ISBN 978-3-319-76230-2 ISBN 978-3-319-76231-9 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76231-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018941557 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018 This work is subject to copyright. -

NORTH CENTRAL WATERWAY STRATEGY 2014-2022 CONTENTS Iii

2014-2022 NORTH CENTRAL WATERWAY STRATEGY Acknowledgement of Country The North Central Catchment Management Authority acknowledges Aboriginal Traditional Owners within the region, their rich culture and spiritual connection to Country. We also recognise and acknowledge the contribution and interest of Aboriginal people and organisations in land and natural resource management. Document name: 2014-22 North Central Waterway Strategy North Central Catchment Management Authority PO Box 18 Huntly Vic 3551 T: 03 5440 1800 F: 03 5448 7148 E: [email protected] www.nccma.vic.gov.au © North Central Catchment Management Authority, 2014 A copy of this strategy is also available online at: www.nccma.vic.gov.au The North Central Catchment Management Authority wishes to acknowledge the Victorian Government for providing funding for this publication through the Victorian Waterway Management Strategy. This publication may be of assistance to you, but the North Central Catchment Management Authority (North Central CMA) and its employees do not guarantee it is without flaw of any kind, or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on information in this publication. The North Central Waterway Strategy was guided by a Steering Committee consisting of: • James Williams (Steering Committee Chair and North Central CMA Board Member) • Richard Carter (Natural Resource Management Committee Member) • Andrea Keleher (Department of Environment and Primary Industries) • Greg Smith (Goulburn-Murray Water) • Rohan Hogan (North Central CMA) • Tess Grieves (North Central CMA). The North Central CMA would like to acknowledge the contributions of the Steering Committee, Natural Resource Management Committee (NRMC) and the North Central CMA Board.