Urban Representations: Cultural Expression, Identity and Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre-Contact Astronomy Ragbir Bhathal

Journal & Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, Vol. 142, p. 15–23, 2009 ISSN 0035-9173/09/020015–9 $4.00/1 Pre-contact Astronomy ragbir bhathal Abstract: This paper examines a representative selection of the Aboriginal bark paintings featuring astronomical themes or motives that were collected in 1948 during the American- Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land in north Australia. These paintings were studied in an effort to obtain an insight into the pre-contact social-cultural astronomy of the Aboriginal people of Australia who have lived on the Australian continent for over 40 000 years. Keywords: American-Australian scientific expedition to Arnhem Land, Aboriginal astron- omy, Aboriginal art, celestial objects. INTRODUCTION tralia. One of the reasons for the Common- wealth Government supporting the expedition About 60 years ago, in 1948 an epic journey was that it was anxious to foster good relations was undertaken by members of the American- between Australia and the US following World Australian Scientific Expedition (AAS Expedi- II and the other was to establish scientific tion) to Arnhem Land in north Australia to cooperation between Australia and the US. study Aboriginal society before it disappeared under the onslaught of modern technology and The Collection the culture of an invading European civilisation. It was believed at that time that the Aborig- The expedition was organised and led by ines were a dying race and it was important Charles Mountford, a film maker and lecturer to save and record the tangible evidence of who worked for the Commonwealth Govern- their culture and society. -

Palaeoworks Technical Papers 9

Palaeoworks Technical Papers 9 Geochemistry and identification of Australian red ochre deposits Mike Smith & Barry Fankhauser National Museum of Australia, Canberra, ACT 2601 and Centre for Archaeological Research, Australian National University, ACT 0200, Australia. Email: [email protected] September 2009 Note This information has been prepared for students and researchers interested in identifying ochre in archaeological contexts. It is open to use by everyone with the proviso that its use is cited in any publications, using the URL as the place of publication. Any comments regarding the information found here should be directed to the authors at the above address. © Mike Smith & Barry Fankhauser 2009 Preface Between 1994 and 1998 the authors undertook a project to look at the feasibility of using geochemical signatures to identify the sources of ochres recovered in archaeological excavations. This research was supported by AIATSIS research grants G94/4879, G96/5222 and G98/6143.The two substantive reports on this research (listed below) have remained unpublished until now and are brought together in this Palaeoworks Technical Paper to make them more generally accessible to students and other researchers. Smith, M. A. and B. Fankhauser (1996) An archaeological perspective on the geochemistry of Australian red ochre deposits: Prospects for fingerprinting major sources. A report to the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Canberra. Smith, M. A. and B. Fankhauser (2003) G96/5222 - Further characterisation and sourcing of archaeological ochres. A report to the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Canberra. The original reports are reproduced substantially as written, with the exception that the tables listing samples from ochre quarries (1996: Tables II/ 1-11) have been revised to include additional samples. -

Australian Aboriginal Art

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online Australian Aboriginal Art Patrick Hutchings To attack one’s neighbours, to pass or to crush and subdue more remote peoples without provocation and solely for the thirst for dominion—what is one to call it but brigandage on a grand scale?1 The City of God, St Augustine of Hippo, IV Ch 6 ‘The natives are extremely fond of painting and often sit hours by me when at work’ 2 Thomas Watling The Australians and the British began their relationship by ‘dancing together’, so writes Inge Clendinnen in her multi-voiced Dancing With Strangers 3 which weaves contemporary narratives of Sydney Cove in 1788. The event of dancing is witnessed to by a watercolour by Lieutenant William Bradley, ‘View in Broken Bay New South Wales March 1788’, which is reproduced by Clendinnen as both a plate and a dustcover.4 By ‘The Australians’ Clendinnen means the Aboriginal pop- ulation. But, of course, Aboriginality is not an Aboriginal concept but an Imperial one. As Sonja Kurtzer writes: ‘The concept of Aboriginality did not even exist before the coming of the European’.5 And as for the terra nullius to which the British came, it was always a legal fiction. All this taken in, one sees why Clendinnen calls the First People ‘The Australians’, leaving most of those with the current passport very much Second People. But: winner has taken, almost, all. The Eddie Mabo case6 exploded terra nullius, but most of the ‘nobody’s land’ now still belongs to the Second People. -

ART ABORIGÈNE, AUSTRALIE — Samedi 7 Mars 2020 — Paris, Salle VV Quartier Drouot Art Aborigène, Australie

ART ABORIGÈNE, AUSTRALIE — Samedi 7 mars 2020 — Paris, Salle VV Quartier Drouot Art Aborigène, Australie Samedi 7 mars 2020 Paris — Salle VV, Quartier Drouot 3, rue Rossini 75009 Paris — 16h30 — Expositions Publiques Vendredi 6 mars de 10h30 à 18h30 Samedi 7 mars de 10h30 à 15h00 — Intégralité des lots sur millon.com Département Experts Index Art Aborigène, Australie Catalogue ................................................................................. p. 4 Biographies ............................................................................. p. 56 Ordres d’achats ...................................................................... p. 64 Conditions de ventes ............................................................... p. 65 Liste des artistes Anonyme .................. n° 36, 95, 96, Nampitjinpa, Yuyuya .............. n° 89 Riley, Geraldine ..................n° 16, 24 .....................97, 98, 112, 114, 115, 116 Namundja, Bob .....................n° 117 Rontji, Glenice ...................... n° 136 Atjarral, Jacky ..........n° 101, 102, 104 Namundja, Glenn ........... n° 118, 127 Sandy, William ....n° 133, 141, 144, 147 Babui, Rosette ..................... n° 110 Nangala, Josephine Mc Donald ....... Sams, Dorothy ....................... n° 50 Badari, Graham ................... n° 126 ......................................n° 140, 142 Scobie, Margaret .................... n° 32 Bagot, Kathy .......................... n° 11 Tjakamarra, Dennis Nelson .... n° 132 Directrice Art Aborigène Baker, Maringka ................... -

RECONCILIATION ACTION PLAN Buŋgul Sydney Festival 2020

RECONCILIATION ACTION PLAN Buŋgul Sydney Festival 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY Sydney Festival would like to acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on which the Festival takes place, and pay respect to the 29 clans of the Eora Nation. We acknowledge that this land falls within the boundaries of the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council. We would also like to acknowledge our Darug neighbours in Parramatta. We pay respect to Elders both past and present, and all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples whichever Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nation they come from. INTRODUCTION Originally launched in 2013, our Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP) outlines our commitment towards improving outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples by creating and fostering an organisational environment that cherishes respect, creates opportunity and builds cultural awareness. Sydney Festival recognises that Sydney is a vast, complex and exuberant city of cultural contrasts and social diversity, that Sydney’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heritage and contemporary cultures lie deep within the city’s identity and are key to an enlightened and progressive festival. COVER IMAGE: ALWAYS Sydney Festival 2019 2 1 Four Thousand Fish Sydney Festival 2018 A MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR The Sydney Festival Reconciliation Action Plan remains our organisation's commitment to ensure that we keep moving forward on this vital issue for our nation. We are committed to working towards improving outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples by creating and fostering an organisational environment that cherishes respect, creates opportunity and builds cultural awareness. We will continue to set ourselves new measurable goals, at the same time as maintaining ongoing successful initiatives as part of the ongoing journey for this organisation and our community. -

STUDY GUIDE by Marguerite O’Hara, Jonathan Jones and Amanda Peacock

A personal journey into the world of Aboriginal art A STUDY GUIDE by MArguerite o’hArA, jonAthAn jones And amandA PeAcock http://www.metromagazine.com.au http://www.theeducationshop.com.au ‘Art for me is a way for our people to share stories and allow a wider community to understand our history and us as a people.’ SCREEN EDUCATION – Hetti Perkins Front cover: (top) Detail From GinGer riley munDuwalawala, Ngak Ngak aNd the RuiNed City, 1998, synthetic polyer paint on canvas, 193 x 249.3cm, art Gallery oF new south wales. © GinGer riley munDuwalawala, courtesy alcaston Gallery; (Bottom) Kintore ranGe, 2009, warwicK thornton; (inset) hetti perKins, 2010, susie haGon this paGe: (top) Detail From naata nunGurrayi, uNtitled, 1999, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 2 122 x 151 cm, mollie GowinG acquisition FunD For contemporary aBoriGinal art 2000, art Gallery oF new south wales. © naata nunGurrayi, aBoriGinal artists aGency ltD; (centre) nGutjul, 2009, hiBiscus Films; (Bottom) ivy pareroultja, rrutjumpa (mt sonDer), 2009, hiBiscus Films Introduction GulumBu yunupinGu, yirrKala, 2009, hiBiscus Films DVD anD WEbsitE short films – five for each of the three episodes – have been art + soul is a groundbreaking three-part television series produced. These webisodes, which explore a selection of exploring the range and diversity of Aboriginal and Torres the artists and their work in more detail, will be available on Strait Islander art and culture. Written and presented by the art + soul website <http://www.abc.net.au/arts/art Hetti Perkins, senior curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait andsoul>. Islander art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and directed by Warwick Thornton, award-winning director of art + soul is an absolutely compelling series. -

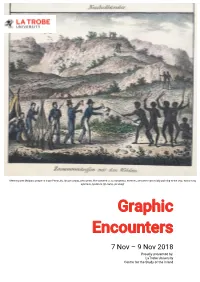

Graphic Encounters Conference Program

Meeting with Malgana people at Cape Peron, by Jacque Arago, who wrote, ‘the watched us as dangerous enemies, and were continually pointing to the ship, exclaiming, ayerkade, ayerkade (go away, go away)’. Graphic Encounters 7 Nov – 9 Nov 2018 Proudly presented by: LaTrobe University Centre for the Study of the Inland Program Melbourne University Forum Theatre Level 1 Arts West North Wing 153 148 Royal Parade Parkville Wednesday 7 November Program 09:30am Registrations 10:00am Welcome to Country by Aunty Joy Murphy Wandin AO 10:30am (dis)Regarding the Savages: a short history of published images of Tasmanian Aborigines Greg Lehman 11.30am Morning Tea 12.15pm ‘Aborigines of Australia under Civilization’, as seen in Colonial Australian Illustrated Newspapers: Reflections on an article written twenty years ago Peter Dowling News from the Colonies: Representations of Indigenous Australians in 19th century English illustrated magazines Vince Alessi Valuing the visual: the colonial print in a pseudoscientific British collection Mary McMahon 1.45pm Lunch 2.45pm Unsettling landscapes by Julie Gough Catherine De Lorenzo and Catherine Speck The 1818 Project: Reimagining Joseph Lycett’s colonial paintings in the 21st century Sarah Johnson Printmaking in a Post-Truth World: The Aboriginal Print Workshops of Cicada Press Michael Kempson 4.15pm Afternoon tea and close for day 1 2 Thursday 8 November Program 10:00am Australian Blind Spots: Understanding Images of Frontier Conflict Jane Lydon 11:00 Morning Tea 11:45am Ad Vivum: a way of being. Robert Neill -

John Gould and David Attenborough: Seeing the Natural World Through Birds and Aboriginal Bark Painting by Donna Leslie*

John Gould and David Attenborough: seeing the natural world through birds and Aboriginal bark painting by Donna Leslie* Abstract The English naturalist and ornithologist, John Gould, visited Australia in the late 1830s to work on a major project to record the birds of Australia. In the early 1960s, around 130 years later, the English naturalist, David Attenborough, visited Australia, too. Like his predecessor, Attenborough also brought with him a major project of his own. Attenborough’s objective was to investigate Aboriginal Australia and he wanted specifically to look for Aboriginal people still painting in the tradition of their ancestors. Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory was his destination. Gould and Attenborough were both energetic young men, and they each had a unique project to undertake. This essay explores aspects of what the two naturalists had to say about their respective projects, revealing through their own published accounts their particular ways of seeing and interpreting the natural world in Australia, and Australian Aboriginal people and their art, respectively. The essay is inspired by the author’s curated exhibition, Seeing the natural world: birds, animals and plants of Australia, held at the Ian Potter Museum of Art from 20 March to 2 June 2013. An exhibition at the Ian Potter Museum of Art, Seeing the natural world: birds, animals and plants of Australia currently showing from 20 March 2013 to 2 June 2013, explores, among other things, lithographs of Australian birds published by the English naturalist and ornithologist John Gould [1804-1881], alongside bark paintings by Mick Makani Wilingarr [c.1905-1985], an Aboriginal artist from Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory (Chisholm 1966; McCulloch 2006: 471; Morphy 2012). -

An Actor Prepares: What Brian Told Me by Liza-Mare Syron

An Actor Prepares: what Brian told me by Liza-Mare Syron “I felt a feeling of shame for not knowing my own heritage, my own history, and my lack of understanding of Culture and its place in performance practice for Aboriginal artists and performers.” An Actor Prepares: what Brian told me by Liza-Mare Syron This original work is published by the Australian Script Centre, trading as AustralianPlays.org 77 Salamanca Place, Hobart 7004 Tasmania, Australia Tel +61 3 6223 4675 Fax +61 3 6223 4678 [email protected] www.australianplays.org ABN 63 4394 56892 © 2011 Liza- Mare Syron MAKING COPIES This work may be copied under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/ You are free: • to copy, distribute and display the work Under the following conditions: • Attribution — You must give the original author credit. • Non-Commercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. • No Derivative Works — You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. AUSTRALIAN SCRIPT CENTRE The Australian Script Centre has been selectively collecting and distributing outstanding Australian playscripts since 1979. The ASC owns and manages the online portal AustralianPlays.org in collaboration with Currency Press, Playlab and Playwriting Australia. For more information contact the ASC at: Tel: +61 3 6223 4675 Fax: +61 3 6223 4678 [email protected] ww.ozscript.org 2 An Actor Prepares: what Brian told me by Liza-Mare Syron I came to my identity as an Aboriginal person in 1979, I was sixteen. -

Central Land Council and Northern Land Council

CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL and NORTHERN LAND COUNCIL Submission to the Productivity Commission Draft Report into Resources Sector Regulation 21 August 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. KEY TERMS ____________________________________________________________ 4 2. INTRODUCTION ________________________________________________________ 5 PART 1 – DETAILED RESPONSE AND COMMENTARY_________________________ 5 3. LEGAL CONTEXT _______________________________________________________ 5 3.1. ALRA NT ______________________________________________________________ 5 3.2. Native Title Act _________________________________________________________ 6 3.3. The ALRA NT is not alternate to the Native Title Act. __________________________ 6 4. POLICY CONTEXT ______________________________________________________ 6 4.1. Land Council Policy Context ______________________________________________ 6 4.2. Productivity Commission consultation context ________________________________ 8 5. RECOMMENDATIONS AND COMMENTS __________________________________ 9 5.1. The EPBC Act, and Northern Territory Environmental Law has recently been subject to specialised review _________________________________________________________ 9 5.2. Pt IV of the ALRA NT has recently been subject to specialised review _____________ 9 5.3. Traditional owners are discrete from the Aboriginal Community and have special rights ____________________________________________________________________ 10 5.4. Free Prior Informed Consent _____________________________________________ 11 5.5. Inaccuracies in the draft Report -

Narrative and Co-Existence: Mediating Between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Stories

Narrative and Co-Existence: Mediating Between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Stories Kathryn Angela Trees BA (Hons) Murdoch University A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Murdoch University November 1998 Abstract This thesis demonstrates how theory and praxis may be integrated within a postcolonial, or more specifically, anticolonial frame. It argues for the necessity of telling, listening and responding to personal narratives as a catalyst for understanding the construction of identities and their relationship to place. This is achieved through a theorisation of narrative and critique of postcolonialism. Three sites of contestation are visited to provide this critique: the “Patterns of Life: The Story of Aboriginal People of Western Australia” exhibition at the Perth Museum; a comparison of Western Australian legislation that governed the lives of Aboriginal people from 1848 to the present and, the life story of Alice Nannup; and, an analysis of the Australian Institute Judicial Association’s “Aboriginal Culture: Law and Change” seminar for magistrates. Most importantly, this work calls for strategies for negotiating a just basis for coexistence between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. ii Table of Contents Abstract ii Table of Contents iii Acknowledgements v Introduction 1 Chapter One Maps of Place: Maps of Identity 11 1.1 Who am I? Who are you? 11 1.2 A metaphor of mapping 19 1.3 Mapping “Lines of Flight” 23 1.4 Learning to trace 24 1.5 Irish gold prospector 26 1.6 Child explorer of mangrove swamps -

Art Gallery of South Australia Major Achievements 2003

ANNUAL REPORT of the ART GALLERY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA for the year 1 July 2003 – 30 June 2004 The Hon. Mike Rann MP, Minister for the Arts Sir, I have the honour to present the sixty-second Annual Report of the Art Gallery Board of South Australia for the Gallery’s 123rd year, ended 30 June 2004. Michael Abbott QC, Chairman Art Gallery Board 2003–2004 Chairman Michael Abbott QC Members Mr Max Carter AO (until 18 January 2004) Mrs Susan Cocks (until 18 January 2004) Mr David McKee (until 20 July 2003) Mrs Candy Bennett (until 18 January 2004) Mr Richard Cohen (until 18 January 2004) Ms Virginia Hickey Mrs Sue Tweddell Mr Adam Wynn Mr. Philip Speakman (commenced 20 August 2003) Mr Andrew Gwinnett (commenced 19 January 2004) Mr Peter Ward (commenced 19 January 2004) Ms Louise LeCornu (commenced 19 January 2004) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Principal Objectives 5 Major Achievements 2003-2004 6 Issues and Trends 9 Major Objectives 2004–2005 11 Resources and Administration 13 Collections 22 3 APPENDICES Appendix A Charter and Goals of the Art Gallery of South Australia 27 Appendix B1 Art Gallery Board 29 Appendix B2 Members of the Art Gallery of South Australia 29 Foundation Council and Friends of the Art Gallery of South Australia Committee Appendix B3 Art Gallery Organisational Chart 30 Appendix B4 Art Gallery Staff and Volunteers 31 Appendix C Staff Public Commitments 33 Appendix D Conservation 36 Appendix E Donors, Funds, Sponsorships 37 Appendix F Acquisitions 38 Appendix G Inward Loans 50 Appendix H Outward Loans 53 Appendix I Exhibitions and Public Programs 56 Appendix J Schools Support Services 61 Appendix K Gallery Guide Tour Services 61 Appendix L Gallery Publications 62 Appendix M Annual Attendances 63 Information Statement 64 Appendix N Financial Statements 65 4 PRINCIPAL OBJECTIVES The Art Gallery of South Australia’s objectives and functions are effectively prescribed by the Art Gallery Act, 1939 and can be described as follows: • To collect heritage and contemporary works of art of aesthetic excellence and art historical or regional significance.