SOLONEC Shared Lives on Nigena Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(WA) from 1938 to 1980 and Its Role in the Cultural Life of Perth

The Fellowship of Australian Writers (WA) from 1938 to 1980 and its role in the cultural life of Perth. Patricia Kotai-Ewers Bachelor of Arts, Master of Philosophy (UWA) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Murdoch University November 2013 ABSTRACT The Fellowship of Australian Writers (WA) from 1938 to 1980 and its role in the cultural life of Perth. By the mid-1930s, a group of distinctly Western Australian writers was emerging, dedicated to their own writing careers and the promotion of Australian literature. In 1938, they founded the Western Australian Section of the Fellowship of Australian Writers. This first detailed study of the activities of the Fellowship in Western Australia explores its contribution to the development of Australian literature in this State between 1938 and 1980. In particular, this analysis identifies the degree to which the Fellowship supported and encouraged individual writers, promoted and celebrated Australian writers and their works, through publications, readings, talks and other activities, and assesses the success of its advocacy for writers’ professional interests. Information came from the organisation’s archives for this period; the personal papers, biographies, autobiographies and writings of writers involved; general histories of Australian literature and cultural life; and interviews with current members of the Fellowship in Western Australia. These sources showed the early writers utilising the networks they developed within a small, isolated society to build a creative community, which welcomed artists and musicians as well as writers. The Fellowship lobbied for a wide raft of conditions that concerned writers, including free children’s libraries, better rates of payment and the establishment of the Australian Society of Authors. -

Ord River Diversion Dam EHR Nomination Rev 2

ENGINEERS AUSTRALIA Western Australia Division NOMINATION OF ORD RIVER DIVERSION DAM FOR AN ENGINEERING HERITAGE AUSTRALIA HERITAGE RECOGNITION AWARD Diversion Dam and Lake Kununurra on July 20, 1963 PREPARED BY ENGINEERING HERITAGE WESTERN AUSTRALIA ENGINEERS AUSTRALIA WESTERN AUSTRALIA DIVISION Revision 2: September 2013 (Original Version: March 2013, Revision 1: Sept 2013) CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 3 2. STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE ................................................................................. 4 3. LOCATION ..................................................................................................................... 5 4. HERITAGE RECOGNITION NOMINATION FORM ....................................................... 7 5. OWNER'S LETTER OF AGREEMENT .......................................................................... 8 6. HISTORICAL SUMMARY .............................................................................................. 9 7. BASIC DATA .................................................................................................................. 10 8. DESCRIPTION OF PROJECT ....................................................................................... 11 8.1 Hydraulic Design Considerations .......................................................................... 11 8.2 Design of Radial Gates and Concrete Works ....................................................... 13 8.3 Site -

Register of Heritage Places - Assessment Documentation

REGISTER OF HERITAGE PLACES - ASSESSMENT DOCUMENTATION HERITAGE COUNCIL OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA 11. ASSESSMENT OF CULTURAL HERITAGE SIGNIFICANCE The criteria adopted by the Heritage Council in November, 1996 have been used to determine the cultural heritage significance of the place. 11. 1 AESTHETIC VALUE * -------------- 11. 2. HISTORIC VALUE The place is located on an early pastoral lease issued in the Kimberley region in 1883. (Criterion 2.1) The cave structures were established as a response to war time threat but were utilised later for educational purposes. (Criterion 2.2) The place is closely associated with the Emanuel family who pioneered the lease in 1883 and also held leases over Christmas Creek, Cherrabun and Meda. (Criterion 2.3) 11. 3. SCIENTIFIC VALUE --------------- 11. 4. SOCIAL VALUE Gogo Cave School contributed to the educational needs of the community and was reputedly the first school to be established on a cattle station in Western Australia. (Criterion 4.1) * For consistency, all references to architectural style are taken from Apperly, R., Irving, R., Reynolds, P., A Pictorial Guide to Identifying Australian Architecture: Styles and Terms from 1788 to the Present Angus & Robertson, North Ryde, 1989. Register of Heritage Places - Assessment Doc’n Gogo Homestead & Cave School 1 11/12/1998 12. DEGREE OF SIGNIFICANCE 12. 1. RARITY The use of man-made caves for educational purposes is unusual in the State. (Criterion 5.1) 12. 2 REPRESENTATIVENESS Gogo Homestead is representative of a north-west station plan, with centre core and surrounding verandahs. 12. 3 CONDITION Gogo Homestead is in good condition although the building requires general maintenance. -

An Annotated Type Catalogue of the Dragon Lizards (Reptilia: Squamata: Agamidae) in the Collection of the Western Australian Museum Ryan J

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 34 115–132 (2019) DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.34(2).2019.115-132 An annotated type catalogue of the dragon lizards (Reptilia: Squamata: Agamidae) in the collection of the Western Australian Museum Ryan J. Ellis Department of Terrestrial Zoology, Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Western Australia 6986, Australia. Biologic Environmental Survey, 24–26 Wickham St, East Perth, Western Australia 6004, Australia. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT – The Western Australian Museum holds a vast collection of specimens representing a large portion of the 106 currently recognised taxa of dragon lizards (family Agamidae) known to occur across Australia. While the museum’s collection is dominated by Western Australian species, it also contains a selection of specimens from localities in other Australian states and a small selection from outside of Australia. Currently the museum’s collection contains 18,914 agamid specimens representing 89 of the 106 currently recognised taxa from across Australia and 27 from outside of Australia. This includes 824 type specimens representing 45 currently recognised taxa and three synonymised taxa, comprising 43 holotypes, three syntypes and 779 paratypes. Of the paratypes, a total of 43 specimens have been gifted to other collections, disposed or could not be located and are considered lost. An annotated catalogue is provided for all agamid type material currently and previously maintained in the herpetological collection of the Western Australian Museum. KEYWORDS: type specimens, holotype, syntype, paratype, dragon lizard, nomenclature. INTRODUCTION Australia was named by John Edward Gray in 1825, The Agamidae, commonly referred to as dragon Clamydosaurus kingii Gray, 1825 [now Chlamydosaurus lizards, comprises over 480 taxa worldwide, occurring kingii (Gray, 1825)]. -

Teachers' Notes the Little Red, Yellow, Black Book

Educational Resources: Teachers’ notes The Little Red Yellow Black website, http://lryb.aiatsis.gov.au Teachers’ Notes The Little Red, Yellow, Black Book: An introduction to Indigenous Australia An important note to teachers The following points are important considerations to remember when teaching Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander studies. These cautions should be consulted throughout the course and shared with students. Aboriginal studies and Torres Strait Islander studies are not only about historical events and contemporary happenings. More importantly, they are about people and their lives. Consequently, consideration of, and sensitivity towards, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are essential, as is collaboration with relevant communities. • Where possible, consult Indigenous people and Indigenous sources for information, many links to which are contained in these notes. Try to work with your local Indigenous community people and elders and respect the intellectual and cultural property rights of Indigenous people. • Consult reliable sources. Be discerning and look for credible information. Indigenous Australians are careful to speak only about the country or culture they’re entitled to speak about. Generally Indigenous people won’t tell others about sacred images or stories, however, over time, and with the effects of colonisation, some things that are sacred, or secret, to Indigenous groups have been disseminated. Be sensitive to requests not to talk about or include some material. Ensure that what you’re reading derives from a community or elders’ knowledge, or from reputable research. Remember too that less-than-polished publications can still be valuable. • Use only the information and images you know have been cleared for reproduction or use in the public domain. -

East Kimberley Impact Assessment Project

East Kimberley Impact Assessment Project HISTORICAL NOTES RELEVANT TO IMPACT STORIES OF THE EAST KIMBERLEY Cathie Clement* East Kimberley Working Paper No. 29 ISBN O 86740 357 8 ISSN 0816...,6323 A Joint Project Of The: Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies Australian National University Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies Anthropology Department University of Western Australia Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia The aims of the project are as follows: 1. To compile a comprehensive profile of the contemporary social environment of the East Kimberley region utilising both existing information sources and limited fieldwork. 2. Develop and utilise appropriate methodological approaches to social impact assessment within a multi-disciplinary framework. 3. Assess the social impact of major public and private developments of the East Kimberley region's resources (physical, mineral and environmental) on resident Aboriginal communities. Attempt to identify problems/issues which, while possibly dormant at present, are likely to have implications that will affect communities at some stage in the future. 4. Establish a framework to allow the dissemination of research results to Aboriginal communities so as to enable them to develop their own strategies for dealing with social impact issues. 5. To identify in consultation with Governments and regional interests issues and problems which may be susceptible to further research. Views expressed in the Projecfs publications are the views of the authors, and are not necessarily shared by the sponsoring organisations. Address correspondence to: The Executive Officer East Kimberley Project CRES, ANU GPO Box4 Canberra City, ACT 2601 HISTORICAL NOTES RELEVANT TO IMPACT STORIES OF THE EAST KIMBERLEY Cathie Clement* East Kimberley Working Paper No. -

No. Area Metro/Rural Agent Year Dup ______

J S Battye Library of West Australian History Collection No. Area Metro/Rural Agent Year Dup ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 ‘William Bay Farm’ Rural 205 Hectares – Rural Land John Garland & Co 1982 2 Narembeen Rural ‘Bega’ 660 Hectares – Farmland John Garland & Co 1982 3 Bruce Rock Rural ‘Mairin’ 883.8 Hectares – Ppn Avon Location John Garland & Co 1981 4 Middle Swan Metro ‘Vineyard House’ 4.27 Ha – Full River Frontage John Garland & Co 1981 5 Murchison Region Rural Meka Station 365,904 Ha – Sheep Station Joseph Charles Learmonth Duffy 19? 6 Goldfields Region Rural Sturt Meadows Station – Pastoral Station Elders 1982 7 Murchison Region Rural Nookawarra Station – Pastoral Station Elders 1982 8 Albany Rural Hotel & Bottle Shop John Garland & Co 1982 9 Esperance Rural Killara Downs 1514 Hectares Elders 1983 10 West Kimberley Rural Anna Plains Station – Cattle Station Joseph Charles Learmonth Region Duffy 19? 11 Serpentine Rural 174.43 Ha – Peel Estate Lots 159, 160 & 385 John Garland & Co 1982 12 Northam Rural 470 Hectares – Buckland Estate John Garland & Co 1982 13 Mount Barker Rural Genesta Estate 432 Hectares – Pastoral John Garland & Co 1982 14 Bald Rock Rural 525 Hectares John Garland & Co 1981 D 15 31 Kinkuna Way Metro Residence John Garland & Co 1982 16 West Wagin Rural Brentwood 875 Hectares John Garland & Co 1981 17 18 Hughenden, Quindanning -Boddington Rural 650 Hectares John Garland & Co 1982 19 Fitzgerald River Rural 5875 Ha – ‘Coladdie Farms’,’Korra Korrenga’ John Garland 1981 20 Kojonup Rural Cheviot Hills – 3136.438 Ha, 7750 acres John P. MacDermott 1981 21 Peppermint Grove Metro 51 Johnston St – Residential Mansion William Porteous 1982 22 Madora Bay Rural Seafront Land H & N Perry 19? PR11263 - 1 - Copyright SLWA 2010 J S Battye Library of West Australian History Collection No. -

By-Elections in Western Australia

By-elections in Western Australia Contents WA By-elections - by date ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 WA By-elections - by reason ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 14 By-elections due to the death of a sitting member ........................................................................................................................................................... 14 Ministerial by-elections.................................................................................................................................................................................................... 16 Fresh election ordered ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 17 Seats declared vacant ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... 17 WA By-elections - by electorate .......................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Art and Artists in Perth 1950-2000

ART AND ARTISTS IN PERTH 1950-2000 MARIA E. BROWN, M.A. This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Design Art History 2018 THESIS DECLARATION I, Maria Encarnacion Brown, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in the degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. No part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. The work(s) are not in any way a violation or infringement of any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. The research involving human data reported in this thesis was assessed and approved by the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee. Approval # RA/4/1/7748. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature: Date: 14 May 2018 i ABSTRACT This thesis provides an account of the development of the visual arts in Perth from 1950 to 2000 by examining in detail the state of the local art scene at five key points in time, namely 1953, 1962, 1975, 1987 and 1997. -

SIS) – 2017 Version

Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites (SIS) – 2017 version Available for download from http://www.eaaflyway.net/about/the-flyway/flyway-site-network/ Categories approved by Second Meeting of the Partners of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership in Beijing, China 13-14 November 2007 - Report (Minutes) Agenda Item 3.13 Notes for compilers: 1. The management body intending to nominate a site for inclusion in the East Asian - Australasian Flyway Site Network is requested to complete a Site Information Sheet. The Site Information Sheet will provide the basic information of the site and detail how the site meets the criteria for inclusion in the Flyway Site Network. When there is a new nomination or an SIS update, the following sections with an asterisk (*), from Questions 1-14 and Question 30, must be filled or updated at least so that it can justify the international importance of the habitat for migratory waterbirds. 2. The Site Information Sheet is based on the Ramsar Information Sheet. If the site proposed for the Flyway Site Network is an existing Ramsar site then the documentation process can be simplified. 3. Once completed, the Site Information Sheet (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Flyway Partnership Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the Information Sheet and, where possible, digital versions (e.g. shapefile) of all maps. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

'A Dying Race': the History and Fiction of Elizabeth Durack

Fresh Cuts: New Talents 2001 ‘A Dying Race’: The History and Fiction of Elizabeth Durack Kylie O’Connell On 25 May 2000, the eve of National Sorry Day and Corroboree 2000, painter Elizabeth Durack died, aged 84.1 Durack grew up on her family’s stations in the Kimberley, north Western Australia. She began her artistic career illustrating children’s storybooks written by her sister, the late Mary Durack, in the 1930s and 1940s. Elizabeth painted throughout her life, mainly depicting the Aborigines who lived on and around her family’s properties. She gained national focus in March 1997, when art historian Robert Smith revealed that she had invented the persona of ‘Eddie Burrup’, an emerging Aboriginal artist. At the time, many non-indigenous critics were sympathetic to Durack’s vocalised aims. Smith noted that ‘Eddie Burrup’ could ‘be seen as not just a homage to Aboriginal Australia, but a concrete exemplar for reconciliation between two communities and two cultures’.2 Other critics, such as the anthropologist Julie Marcus, disagreed. Marcus argued that Durack’s deception: offers a timely opportunity to examine some of the ways in which a colonial politics of dispossession, race, gender and an undoubted sympathy for Aboriginal people play out through the work and thought of an individual artist.3 This article builds on Marcus’ argument, demonstrating how Durack’s art retraced the history of colonial relationships between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians. Durack’s invention of Burrup, and in particular his ‘autobiography’, helped create and maintain his ‘material’ identity as an artist. Burrup stood before Durack’s ‘Aboriginal’ paintings, signifying their beginning or genesis. -

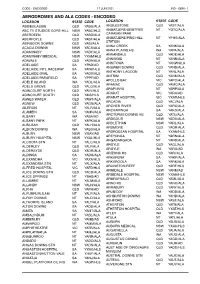

Aerodromes and Ala Codes

CODE - ENCODED 17 JUN 2021 IND - GEN - 1 AERODROMES AND ALA CODES - ENCODED LOCATION STATE CODE LOCATION STATE CODE ABBIEGLASSIE QLD YABG/ALA ANGLESTONE QLD YAST/ALA ABC TV STUDIOS GORE HILL NSW YABC/HLS ANMATJERE/GEMTREE NT YGTC/ALA ABERDEEN QLD YABD/ALA CARAVAN PARK ABERFOYLE QLD YABF/ALA ANMATJERE/PINE HILL NT YPHS/ALA STATION ABINGDON DOWNS QLD YABI/ALA ANNA CREEK SA YANK/ALA ACACIA DOWNS NSW YACS/ALA ANNA PLAINS HS WA YAPA/ALA ADAMINABY NSW YADY/ALA ANNANDALE QLD YADE/ALA ADAMINABY MEDICAL NSW YXAM/HLS ANNINGIE NT YANN/ALA ADAVALE QLD YADA/ALA ANNITOWA NT YANW/ALA ADELAIDE SA YPAD/AD ANSWER DOWNS QLD YAND/ALA ADELAIDE INTL RACEWAY SA YAIW/HLS ANTHONY LAGOON NT YANL/ALA ADELAIDE OVAL SA YAOV/HLS ANTRIM QLD YANM/ALA ADELAIDE/PARAFIELD SA YPPF/AD APOLLO BAY VIC YAPO/ALA ADELE ISLAND WA YADL/ALA ARAMAC QLD YAMC/ALA ADELS GROVE QLD YALG/ALA ARAPUNYA NT YARP/ALA AGINCOURT NORTH QLD YAIN/HLS ARARAT VIC YARA/AD AGINCOURT SOUTH QLD YAIS/HLS ARARAT HOSPITAL VIC YXAR/HLS AGNES WATER QLD YAWT/ALA ARCADIA QLD YACI/ALA AGNEW QLD YAGN/ALA ARCHER RIVER QLD YARC/ALA AILERON NT YALR/ALA ARCKARINGA SA YAKG/ALA ALAMEIN SA YAMN/ALA ARCTURUS DOWNS HS QLD YATU/ALA ALBANY WA YABA/AD ARDGOUR NSW YADU/ALA ALBANY PARK NT YAPK/ALA ARDLETHAN NSW YARL/ALA ALBILBAH QLD YALH/ALA ARDMORE QLD YAOR/ALA ALBION DOWNS WA YABS/ALA ARDROSSAN HOSPITAL SA YXAN/HLS ALBURY NSW YMAY/AD AREYONGA NT YARN/ALA ALBURY HOSPITAL NSW YXAL/HLS ARGADARGADA NT YARD/ALA ALCOOTA STN NT YALC/ALA ARGYLE QLD YAGL/ALA ALDERLEY QLD YALY/ALA ARGYLE WA YARG/AD ALDERSYDE QLD YADR/ALA ARIZONA HS