Action Research to Build the Capacity of Nyikina Indigenous Australians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOLONEC Shared Lives on Nigena Country

Shared lives on Nigena country: A joint Biography of Katie and Frank Rodriguez, 1944-1994. Jacinta Solonec 20131828 M.A. Edith Cowan University, 2003., B.A. Edith Cowan University, 1994 This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities (Discipline – History) 2015 Abstract On the 8th of December 1946 Katie Fraser and Frank Rodriguez married in the Holy Rosary Catholic Church in Derby, Western Australia. They spent the next forty-eight years together, living in the West Kimberley and making a home for themselves on Nigena country. These are Katie’s ancestral homelands, far from Frank’s birthplace in Galicia, Spain. This thesis offers an investigation into the social history of a West Kimberley couple and their family, a couple the likes of whom are rarely represented in the history books, who arguably typify the historic multiculturalism of the Kimberley community. Katie and Frank were seemingly ordinary people, who like many others at the time were socially and politically marginalised due to Katie being Aboriginal and Frank being a migrant from a non-English speaking background. Moreover in many respects their shared life experiences encapsulate the history of the Kimberley, and the experiences of many of its people who have been marginalised from history. Their lives were shaped by their shared faith and Katie’s family connections to the Catholic mission at Beagle Bay, the different governmental policies which sought to assimilate them into an Australian way of life, as well as their experiences working in the pastoral industry. -

Register of Heritage Places - Assessment Documentation

REGISTER OF HERITAGE PLACES - ASSESSMENT DOCUMENTATION HERITAGE COUNCIL OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA 11. ASSESSMENT OF CULTURAL HERITAGE SIGNIFICANCE The criteria adopted by the Heritage Council in November, 1996 have been used to determine the cultural heritage significance of the place. 11. 1 AESTHETIC VALUE * -------------- 11. 2. HISTORIC VALUE The place is located on an early pastoral lease issued in the Kimberley region in 1883. (Criterion 2.1) The cave structures were established as a response to war time threat but were utilised later for educational purposes. (Criterion 2.2) The place is closely associated with the Emanuel family who pioneered the lease in 1883 and also held leases over Christmas Creek, Cherrabun and Meda. (Criterion 2.3) 11. 3. SCIENTIFIC VALUE --------------- 11. 4. SOCIAL VALUE Gogo Cave School contributed to the educational needs of the community and was reputedly the first school to be established on a cattle station in Western Australia. (Criterion 4.1) * For consistency, all references to architectural style are taken from Apperly, R., Irving, R., Reynolds, P., A Pictorial Guide to Identifying Australian Architecture: Styles and Terms from 1788 to the Present Angus & Robertson, North Ryde, 1989. Register of Heritage Places - Assessment Doc’n Gogo Homestead & Cave School 1 11/12/1998 12. DEGREE OF SIGNIFICANCE 12. 1. RARITY The use of man-made caves for educational purposes is unusual in the State. (Criterion 5.1) 12. 2 REPRESENTATIVENESS Gogo Homestead is representative of a north-west station plan, with centre core and surrounding verandahs. 12. 3 CONDITION Gogo Homestead is in good condition although the building requires general maintenance. -

The Southern Arizona Guest Ranch As a Symbol of the West

The Southern Arizona guest ranch as a symbol of the West Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Norris, Frank B. (Frank Blaine), 1950-. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 15:00:58 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/555065 THE SOUTHERN ARIZONA GUEST RANCH AS A SYMBOL OF THE WEST by Frank Blaine Norris A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT, AND URBAN PLANNING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN GEOGRAPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 6 Copyright 1976 Frank Blaine Norris STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfill ment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowl edgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. SIGNED: APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis is the collective effort of many, and to each who played a part in its compilation, I am indebted. -

An Annotated Type Catalogue of the Dragon Lizards (Reptilia: Squamata: Agamidae) in the Collection of the Western Australian Museum Ryan J

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 34 115–132 (2019) DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.34(2).2019.115-132 An annotated type catalogue of the dragon lizards (Reptilia: Squamata: Agamidae) in the collection of the Western Australian Museum Ryan J. Ellis Department of Terrestrial Zoology, Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Western Australia 6986, Australia. Biologic Environmental Survey, 24–26 Wickham St, East Perth, Western Australia 6004, Australia. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT – The Western Australian Museum holds a vast collection of specimens representing a large portion of the 106 currently recognised taxa of dragon lizards (family Agamidae) known to occur across Australia. While the museum’s collection is dominated by Western Australian species, it also contains a selection of specimens from localities in other Australian states and a small selection from outside of Australia. Currently the museum’s collection contains 18,914 agamid specimens representing 89 of the 106 currently recognised taxa from across Australia and 27 from outside of Australia. This includes 824 type specimens representing 45 currently recognised taxa and three synonymised taxa, comprising 43 holotypes, three syntypes and 779 paratypes. Of the paratypes, a total of 43 specimens have been gifted to other collections, disposed or could not be located and are considered lost. An annotated catalogue is provided for all agamid type material currently and previously maintained in the herpetological collection of the Western Australian Museum. KEYWORDS: type specimens, holotype, syntype, paratype, dragon lizard, nomenclature. INTRODUCTION Australia was named by John Edward Gray in 1825, The Agamidae, commonly referred to as dragon Clamydosaurus kingii Gray, 1825 [now Chlamydosaurus lizards, comprises over 480 taxa worldwide, occurring kingii (Gray, 1825)]. -

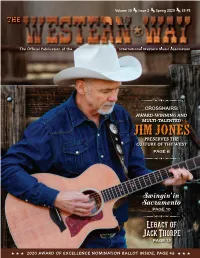

Spring 2020 $5.95 THE

Volume 30 Issue 2 Spring 2020 $5.95 THE The Offi cial Publication of the International Western Music Association CROSSHAIRS: AWARD-WINNING AND MULTI-TALENTED JIM JONES PRESERVES THE CULTURE OF THE WEST PAGE 6 Swingin’ in Sacramento PAGE 10 Legacy of Jack Thorpe PAGE 12 ★ ★ ★ 2020 AWARD OF EXCELLENCE NOMINATION BALLOT INSIDE, PAGE 46 ★ ★ ★ __WW Spring 2020_Cover.indd 1 3/18/20 7:32 PM __WW Spring 2020_Cover.indd 2 3/18/20 7:32 PM 2019 Instrumentalist of the Year Thank you IWMA for your love & support of my music! HaileySandoz.com 2020 WESTERN WRITERS OF AMERICA CONVENTION June 17-20, 2020 Rushmore Plaza Holiday Inn Rapid City, SD Tour to Spearfish and Deadwood PROGRAMMING ON LAKOTA CULTURE FEATURED SPEAKER Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve SESSIONS ON: Marketing, Editors and Agents, Fiction, Nonfiction, Old West Legends, Woman Suffrage and more. Visit www.westernwriters.org or contact wwa.moulton@gmail. for more info __WW Spring 2020_Interior.indd 1 3/18/20 7:26 PM FOUNDER Bill Wiley From The President... OFFICERS Robert Lorbeer, President Jerry Hall, Executive V.P. Robert’s Marvin O’Dell, V.P. Belinda Gail, Secretary Diana Raven, Treasurer Ramblings EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Marsha Short IWMA Board of Directors, herein after BOD, BOARD OF DIRECTORS meets several times each year; our Bylaws specify Richard Dollarhide that the BOD has to meet face to face for not less Juni Fisher Belinda Gail than 3 meetings each year. Jerry Hall The first meeting is usually in the late January/ Robert Lorbeer early February time frame, and this year we met Marvin O’Dell Robert Lorbeer Theresa O’Dell on February 4 and 5 in Sierra Vista, AZ. -

CONSUMING LINCOLN: ABRAHAM LINCOLN's WESTERN MANHOOD in the URBAN NORTHEAST, 1848-1861 a Dissertation Submitted to the Kent S

CONSUMING LINCOLN: ABRAHAM LINCOLN’S WESTERN MANHOOD IN THE URBAN NORTHEAST, 1848-1861 A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By David Demaree August 2018 © Copyright All right reserved Except for previously published materials A dissertation written by David Demaree B.A., Geneva College, 2008 M.A., Indiana University of Pennsylvania, 2012 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2018 Approved by ____________________________, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Kevin Adams, Ph.D. ____________________________, Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Elaine Frantz, Ph.D. ____________________________, Lesley J. Gordon, Ph.D. ____________________________, Sara Hume, Ph.D. ____________________________ Robert W. Trogdon, Ph.D. Accepted by ____________________________, Chair, Department of History Brian M. Hayashi, Ph.D. ____________________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences James L. Blank, Ph.D. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ..............................................................................................................iii LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS...............................................................................................................v INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................................1 -

The Invasion of Sturt Creek Basin (Kimberley Region, Western Australia)

Into the Kimberley: the invasion of the Sturt Creek Basin (Kimberley region, Western Australia) and evidence of Aboriginal resistance Pamela A Smith The extent to which the traditional owners of the upper Sturt Creek basin in the south east Kimberley region resisted the exploration and colonisation of their country in the late nineteenth century is generally underestimated and seldom referred to in historical records. This paper documents the exploration and colonisation of the region and anal yses accounts of frontier conflict recorded in diaries and other historical documents from this period. These documents provide evidence of many incidents which, when viewed together, suggest that the traditional owners resisted colonisation as best they could without guns, and that the colonists perceived themselves as invaders. The southeast Kimberley was one of the last regions of Australia to be colonised by Europeans. The upper Sturt Creek basin, which occupies much of the southeast Kim berley (Figure 1), was the route used by the first European explorers entering the east Kimberley and a major route used by the first pastoralists entering the Kimberley with herds of cattle from Queensland. Much of this land was, and is, the traditional country of Nyininy language speak ers (a dialect of Jaru).1 Explorers and early pastoralists would have passed close to, if not through, several important meeting places of the Nyininy including Sweetwater on the Sturt Creek and Wan.gu (or Wungu) near Old Flora Valley (Tsunoda 1981: xvi, 6-7). This study examines the nature of the interaction between the explorers, the colonising pastoralists and the traditional owners, the Nyininy. -

Fitzroy River National Park Plan Creating Steady Flow of Concerns from Kimberley Cattle Industry

Rural Fitzroy River National Park plan creating steady flow of concerns from Kimberley cattle industry ABC Rural By Matt Brann Updated yesterday at 13:37 First posted yesterday at 06:02 Environmentalists hope a Fitzroy River National Park will protect the region from dam proposals at Dimond Gorge and on the Margaret River (pictured). (Matt Brann: ABC) There are growing concerns among the Kimberley cattle industry over a government plan to create the Fitzroy River National Park. The park was an election promise by the Western Australian Labor Government, and has strong backing from environmentalists and some traditional owners. But president of the Pastoralists and Graziers Association (PGA), Tony Seabrook, said some of his members were very worried about the park and what it could mean for neighbouring properties and local stations looking to diversify. "Government needs to be able to look after the estate it currently controls in a far better fashion before they take more," Mr Seabrook said. "This [national park] would be very detrimental for the properties which adjoin the river. "There are certainly some sites on that river of great significance, but the park is too big, too over-reaching and probably ungovernable." Gogo Station is seeking approvals to grow more irrigated fodder crops for its cattle. (ABC Rural: Matt Brann) Gogo Station irrigation plans under pressure One cattle station concerned about the impacts of the planned national park is Gogo Station, east of Fitzroy Crossing. Owned by the Harris family since 1989, the station has been growing irrigated sorghum for its cattle using two centre pivots for several years, and is seeking approvals to expand. -

Looking Back to Look Forward: a Timeline of the Fitzroy River Catchment

Looking back to look forward: A timeline of the Fitzroy River catchment This story map describes a timeline of key events that have shaped the Fitzroy River catchment, Western Australia. It was created in a scenario planning exercise to help understand and explore the driving forces of development in the region. Danggu Geikie Gorge, Fitzroy River, circa 1886. © State Library of Western Australia, B2801181 Citation: Álvarez-Romero, J.G. and R. Buissereth. 2021. Looking back to look forward: A timeline of the Fitzroy River catchment, Story Map. James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia. URL: https://arcg.is/1jXi9P Acknowledgements We acknowledge the Traditional Owners and Custodians of Country throughout Australia and their connections to land, water, and community. We pay our respect to their elders past and present and extend that respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples today. In particular, we wish to acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the Martuwarra (Fitzroy River) catchment, the Bunuba, Giniyjawarrni Yoowaniya Riwi, Gooniyandi, Jaru, Kurungal, Ngarrawanji, Nyikina, Mangala, Warrwa, Yi- Martuwarra Ngurrara, Yungngora, and Yurriyangem Taam peoples. We recognize their continuing culture and contributions to the Kimberley region and Australia. Credits We thank the contributions of Karen Dayman from the Kimberley Land Council/Northern Australia Environmental Resources Hub, the scenario planning team, and the research team from James Cook University, The University of Western Australia, CSIRO, Griffith University, and the University of Tasmania. We also thank Dave Munday and Liz Brown for facilitating the workshops. The project was funded by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program through its Northern Australia Environmental Resources Hub. -

Why Would a Pastoralist Invest in Irrigation to Grow Fodder in Western Australia?

Why would a pastoralist invest in irrigation to grow fodder in Western Australia? • Christopher Ham • Senior Development Officer • Irrigation and Pastoral Diversification • Broome, Western Australia • Twitter: @ChrisHamDPIRD Our region – NW Western Australia Mosaic Agriculture Red dots indicate irrigation sites across the West Kimberley and Northern Pilbara Investment into irrigation in the last 20 years Shelamar Horticulture Pardoo Stages 1, 2 & 3 Shamrock Gardens Kilto Plus Anna Plains Nita Downs Mowanjum Liveringa Gogo Wallal Downs Stage 1 Wallal Downs Stage 2 Skuthorpe Stage 1 and others… What is driving the investment? • Isolation and freight costs • Limited rainfall (<800 mm) • Limitations of natural pastures • Pastoral landscape & policy • Supply chain & abattoir • Market forces Kimberley Meat Company Water source & development costs Shallow groundwater (Centre pivot) Total capital costs per ha - $12,233 - $20,000 (CSIRO, 2018) Artesian groundwater (Centre pivot) Total capital costs per ha - $14,400 – $21,000 (Plunkett, Wiley 2017) Surface water capture (Surface or pivot) Total capital costs per ha - $10,000 - $21,600 (CSIRO, 2018) High value horticulture (drip tape) Total capital costs per ha - $40,951 (CSIRO, 2018) - $50,000 (FPG, 2018) Hay, silage & stand and graze Crop options and rotations Perennial tropical grasses • C4 tropical grasses – Rhodes or Panics • High growth in the Wet season • Lower growth in the Dry season • Mixed pastures – difficult to maintain Annual rotations Dry season options • Cut and carry/silage – Maize -

Register of Heritage Places - Assessment Documentation

REGISTER OF HERITAGE PLACES - ASSESSMENT DOCUMENTATION HERITAGE COUNCIL OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA 11. ASSESSMENT OF CULTURAL HERITAGE SIGNIFICANCE The criteria adopted by the Heritage Council in November, 1996 have been used to determine the cultural heritage significance of the place. 11. 1 AESTHETIC VALUE * The place is situated in an attractive setting, with the homestead on a hill overlooking a billabong on a branch of the Fitzroy River. The Grant Ranges to the west of the homestead, form an impressive backdrop. Terraced gardens and lawns contribute to the aesthetic appeal of the place. (Criterion 1.1) The elevated position of the homestead gives it a landmark quality. (Criterion 1.3) The buildings and associated outbuildings form a significant pastoral precinct. (Criterion 1.4) 11. 2. HISTORIC VALUE The place is associated with the early pastoral settlement of the Kimberley, specifically by the Kimberley Pastoral Company in 1881. The shareholders of the Pastoral Company formed extensive political, economic and social networks throughout Western Australia. (Criterion 2.1) The place was the first polling station in the area for the Commonwealth elections in 1901. (Criterion 2.2) During World War II, the Kimberley region formed a vital zone in Australia's defence strategy. From 1942 to 1943, local volunteers, an Army signals unit and a Royal Australian Air Force radar unit were based at Liveringa Station. (Criterion 2.2) The place is associated with agricultural experimentation incorporating innovative irrigation methods in the 1950s and 60s. (Criterion 2.2) 11. 3. SCIENTIFIC VALUE * For consistency, all references to architectural style are taken from Apperly, R., Irving, R., Reynolds, P., A Pictorial Guide to Identifying Australian Architecture: Styles and Terms from 1788 to the Present Angus & Robertson, North Ryde, 1989. -

Looking West: a Guide to Aboriginal Records in Western Australia

A Guide to Aboriginal Records in Western Australia The Records Taskforce of Western Australia ¨ ARTIST Jeanette Garlett Jeanette is a Nyungar Aboriginal woman. She was removed from her family at a young age and was in Mogumber Mission from 1956 to 1968, where she attended the Mogumber Mission School and Moora Junior High School. Jeanette later moved to Queensland and gained an Associate Diploma of Arts from the Townsville College of TAFE, majoring in screen printing batik. From 1991 to present day, Jeanette has had 10 major exhibitions and has been awarded four commissions Australia-wide. Jeanette was the recipient of the Dick Pascoe Memorial Shield. Bill Hayden was presented with one of her paintings on a Vice Regal tour of Queensland. In 1993 several of her paintings were sent to Iwaki in Japan (sister city of Townsville in Japan). A recent major commission was to create a mural for the City of Armadale (working with Elders and students from the community) to depict the life of Aboriginal Elders from 1950 to 1980. Jeanette is currently commissioned by the Mundaring Arts Centre to work with students from local schools to design and paint bus shelters — the established theme is the four seasons. Through her art, Jeanette assists Aboriginal women involved in domestic and traumatic situations, to express their feelings in order to commence their journey of healing. Jeanette currently lives in Northam with her family and is actively working as an artist and art therapist in that region. Jeanette also lectures at the O’Connor College of TAFE. Her dream is to have her work acknowledged and respected by her peers and the community.