Part I Colonizing the Maya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Song of Kriol: a Grammar of the Kriol Language of Belize

The Song of Kriol: A Grammar of the Kriol Language of Belize Ken Decker THE SONG OF KRIOL: A GRAMMAR OF THE KRIOL LANGUAGE OF BELIZE Ken Decker SIL International DIS DA FI WI LANGWIJ Belize Kriol Project This is a publication of the Belize Kriol Project, the language and literacy arm of the National Kriol Council No part of this publication may be altered, and no part may be reproduced in any form without the express permission of the author or of the Belize Kriol Project, with the exception of brief excerpts in articles or reviews or for educational purposes. Please send any comments to: Ken Decker SIL International 7500 West Camp Wisdom Rd. Dallas, TX 75236 e-mail: [email protected] or Belize Kriol Project P.O. Box 2120 Belize City, Belize c/o e-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Copies of this and other publications of the Belize Kriol Project may be obtained through the publisher or the Bible Society Bookstore 33 Central American Blvd. Belize City, Belize e-mail: [email protected] © Belize Kriol Project 2005 ISBN # 978-976-95215-2-0 First Published 2005 2nd Edition 2009 Electronic Edition 2013 CONTENTS 1. LANGUAGE IN BELIZE ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 AN INTRODUCTION TO LANGUAGE ........................................................................................................ 1 1.2 DEFINING BELIZE KRIOL AND BELIZE CREOLE ...................................................................................... 2 1.3 -

Petition to the Administrative Council of the European Patent Organization

August 10, 2019 BY EMAIL Petition to the Administrative Council of the European Patent Organization Cc: Antonio Campinos, President of the EPO Emmanuel Macron, President, French Republic Christoph Ernst, VP Legal/ International Affairs Angela Merkel, Chancellor, Germany Karin Seegert, COO, Healthcare & Chemistry Mark Rutte, Prime Minister, The Netherlands Piotr Wierzejewski, Quality Management Boris Johnson, Prime Minister, United Kingdom Stoyan Radkov - Applicant’s Representative Cornelia Rudloff-Schäffer, President, German PTO Tim Moss, CEO, Intellectual Property Office of Cadre Philippe, Director, French National Institute the United Kingdom of Industrial Property Vincentia Rosen-Sandiford, Director, Netherlands Patent Office Re: European patent application 09735962.4; and European divisional application 17182663.9; Applicant: Asha Nutrition Sciences, Inc. Dear Delegates in the Administrative Council, We have been prosecuting the referenced patent applications directed to critical innovations for public health at EPO for last 10 years. However, rather than advancing the innovations EPO has been obstructing them. EPO statements in the prosecution history evidence that rejections have been applied to oblige us to reduce the claimed scope, even though as per provisions of European Patent Convention, the subject claims are perfectly patentable. A narrow patent is not synonymous with a quality patent. The metric of quality disregarded by EPO is genuine innovation, measured by betterment of life achieved, though that is the very purpose of patents and is built into the law. For example, solutions to critical unmet needs are inventive even if claims are otherwise obvious (GL1, G-VII, 10.3). Narrow patents in the nutrition arts have already caused great harm to public health and created patent-practice- made humanitarian crises by creating misinformation and taken us farther away from solving nutritional problems, preventative solutions, and sustainability. -

Niop Trading Rules

NIOP TRADING RULES Effective July 2013 Minor changes and corrections (approved by the NIOP Technical Committee) have been included as of July 29, 2013 APPLICATION OF RULES INCORPORATION OF THESE RULES OR ANY PORTION THEREOF IS NOT MANDATORY BUT IS OPTIONAL BETWEEN PARTIES TO CONTRACTS. Published by the National Institute of Oilseed Products 750 National Press Building, 529 14th St NW Washington, D.C. 20045 TEL: (202) 591-2438 FAX: (202) 591-2445 e-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.niop.org ©2013 by the National Institute of Oilseed Products NIOP TRADING RULES TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 - TYPES OF SALES RULE 1.1 TRADE PRACTICE 1 -1 1.2 PLACE OF CONTRACT 1 -1 1.3 C.I.F. (COST, INSURANCE AND FREIGHT) 1 -1 LISTING OF DOCUMENTS 1 -2 1.4 C.& F. (COST AND FREIGHT) 1 -3 1.5 F.O.B. VESSEL (FREE ON BOARD VESSEL) 1 -3 1.6 F.A.S. VESSEL (FREE ALONGSIDE) -NAMED PORT OF SHIPMENT 1 -5 1.7 EX DOCK (NAMED PORT OF IMPORTATION) 1 -6 1.8 EX WAREHOUSE 1 -7 1.9 MISCELLANEOUS TYPES OF SALES 1 -7 1.10 VESSEL CLASSIFICATION 1 -7 1.11 PUBLIC HEALTH SECURITY AND BIOTERRORISM PREPAREDNESS 1 -7 CHAPTER 2 - SHIPMENT RULE 2.1 TIME 2 -1 2.2 DAYS OR HOURS 2 -1 2.3 NOTICE 2 -1 2.4 TENDERS 2 -1 2.5 EXTENSION OF SHIPMENT 2 -1 2.6 PROOF OF ORIGIN 2 -3 2.7 TRANSHIPMENT 2 -3 2.8 SHIPPING INSTRUCTIONS 2 -3 2.9 VESSEL NOMINATION AND DECLARATION OF DESTINATION 2 -3 2.10 BILL OF LADING-EVIDENCE OF DATE OF SHIPMENT 2 -3 CHAPTER 3 - TANK CARS, TRUCKS, BARGES AND CONTAINERS RULE 3.1 DATE OF SHIPMENT 3 -1 3.2 TIME OF SHIPMENT 3 -1 3.3 SPREAD (SCATTERED) DELIVERIES OF SHIPMENTS 3 -1 3.4 F.O.B. -

The Geography of Fishing in British Honduras and Adjacent Coastal Areas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1966 The Geography of Fishing in British Honduras and Adjacent Coastal Areas. Alan Knowlton Craig Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Craig, Alan Knowlton, "The Geography of Fishing in British Honduras and Adjacent Coastal Areas." (1966). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1117. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1117 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been „ . „ i i>i j ■ m 66—6437 microfilmed exactly as received CRAIG, Alan Knowlton, 1930— THE GEOGRAPHY OF FISHING IN BRITISH HONDURAS AND ADJACENT COASTAL AREAS. Louisiana State University, Ph.D., 1966 G eo g rap h y University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE GEOGRAPHY OP FISHING IN BRITISH HONDURAS AND ADJACENT COASTAL AREAS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State university and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Alan Knowlton Craig B.S., Louisiana State university, 1958 January, 1966 PLEASE NOTE* Map pages and Plate pages are not original copy. They tend to "curl". Filmed in the best way possible. University Microfilms, Inc. AC KNQWLEDGMENTS The extent to which the objectives of this study have been acomplished is due in large part to the faithful work of Tiburcio Badillo, fisherman and carpenter of Cay Caulker Village, British Honduras. -

Rassegna Stampa Fids

Direzione Marketing e Comunicazione – Ufficio Stampa RASSEGNA STAMPA FIDS Maggio – Dicembre 2019 ANSA http://www.ansa.it/emiliaromagna/notizie/2019/05/15/a-rimini-leuropeo-di-street-dance_304aa318-4e1f- 416c-a968-f3bff0822c45.html Direzione Marketing e Comunicazione FIDS Responsabile: Dionisio Ciccarese per l’Ufficio Stampa Alessandro Montone (333 3911417) Direzione Marketing e Comunicazione – Ufficio Stampa ADNKRONOS BREAKDANCE: EUROPEI A RIMINI DAL 16 AL 19 MAGGIO = Roma, 15 mag. - (AdnKronos) - Rimini si infiamma con le sfide e le battaglie delle Urban Dance. Al Rds Stadium è tutto pronto per l'appuntamento con l'Europeo di Breakdance, Hip Hop e Electric Boogie, promosso dalla Ido (International dance organization) che per quattro giorni, dal 16 al 19 maggio, trasformerà la città romagnola in un vero tempio delle street dance internazionali. Sul dancefloor riminese sono attesi oltre 2.000 atleti, proveniente da 26 Nazioni che si sfideranno in evoluzioni, battle e gare one to one nei cyper e nelle arene tipiche dell'arti di strada. A scendere in pista le categorie Children, Junior e Adult suddivise a loro volta in Solo Male, Solo Female, Duo, Group e Formation che vedranno gareggiare le unità competitive under 11, 12/15 e 16/Oltre. Grande attenzione sarà riservata alle gare di Breakdance degli atleti 12/15 in quanto i migliori potranno andare a formare la nuova nazionale under 18 che potrà partecipare alle selezioni per le Olimpiadi Giovanile che si terranno in Senegal nel 2022. (segue) (Spr/AdnKronos) ISSN 2465 – 122 - 15-MAG-19 12:37 . NNNN BREAKDANCE: EUROPEI A RIMINI DAL 16 AL 19 MAGGIO (2) = (AdnKronos) - La Break sarà inoltre protagonista nella categoria 16/Oltre con i ''Fantastici 4'' della FIDS: Alessandra Cortesia (Bgirl Lexy), Alex Mammì (Bboy Lele), Eleonora Mereu (Bgirl Kobra) e Mattia Schinco (Bboy Bad Matty) che oltre a puntare alla vittoria nell'Europeo riminese comporranno la Nazionale Azzurra che a fine luglio parteciperà al Mondiale di breakdance in Cina. -

The Soap Making Companion a Guide for Beginners 2Nd Edition

The Soap Making Companion A Guide for Beginners 2nd Edition The companion guidebook to the Thermal Mermaid Artisan Soap Makers Course By Thermal Mermaid & Jennifer Tynan Copyright 2020 by SpeckledEggPublishing All rights reserved. This book, or parts within may not be reproduced without permission from the publisher. Published by SpeckledEggPublishing Waterbury, CT 06706 https://speckledeggpublishing.com Contains material edited and modified from The Soap Making Companion: A Guide for Beginners, 1st Edition, by Jennifer Tynan, copyright 2018, 2015. ISBN: 9798643284789 Printed in the United States of America This publication is designed to provide accurate information in respect to the material presented. It is sold with the understanding that the recipes and suggestions are personal thoughts and understanding on the artisan craft of soap making and is not engaged in professional or medical advice. No claims are made about any of the recipes regarding cures, therapies, or treatments for personal care. Soap is made for cleaning, and the recipes in this book are geared toward the artistic techniques in creating only soap. Photography by Jennifer Tynan 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 2 Table of Contents Introduction 1. 1: Soaping, Setup, & Safety Welcome to the Beginning Gather the Supplies You Need Lye Safety & First Aid How to Mix & Use Lye Properly Saponification & Lye Calculations by Hand First Simple Soap Recipe 2. Cold Process Method, Techniques & Designs White Soap Trace Lavender Flowers Gel Insulating Glycerin Rivers Soda Ash Neapolitan Clay Bar Salt Bar & Brine Drop Swirl Soap 3 Hangar Swirl In the Bowl Swirl Column Pour Peacock Swirl Lava Bubbles 3. -

Redalyc.Diaspora Sounds from Caribbean Central America

Caribbean Studies ISSN: 0008-6533 [email protected] Instituto de Estudios del Caribe Puerto Rico Stone, Michael Diaspora Sounds from Caribbean Central America Caribbean Studies, vol. 36, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2008, pp. 221-235 Instituto de Estudios del Caribe San Juan, Puerto Rico Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=39215107020 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative WATCHING THE CARIBBEAN...PART II 221 Diaspora Sounds from Caribbean Central America Michael Stone Program in Latin American Studies Princeton University [email protected] Garifuna Drum Method. Produced by Emery Joe Yost and Matthew Dougherty. English and Garifuna with subtitles. Distributed by End of the Line Productions/ Lubaantune Records, 2008. DVD. Approximately 100 minutes, color. The Garifuna: An Enduring Spirit. Produced by Robert Flanagan and Suzan Al-Doghachi. English and Garifuna with subtitles. Lasso Pro- ductions, 2003. Distributed by Lasso Productions. DVD. 35 minutes, color. The Garifuna Journey. Produced by Andrea Leland and Kathy Berger. English and Garifuna with subtitles. New Day Films, 1998. Distributed by New Day Films. DVD and study guide. 47 minutes, color. Play, Jankunú, Play: The Garifuna Wanáragua Ritual of Belize. Produced by Oliver Greene. English and Garifuna with subtitles. Distributed by Documentary Educational Resources, 2007. DVD. 45 minutes, color. Trois Rois/ Three Kings of Belize. Produced by Katia Paradis. English, Spanish, Garifuna, and K’ekchi Maya with subtitles (French-language version also available). -

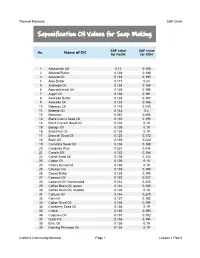

Saponification Oil Values for Soap Making

Thermal Mermaid SAP Chart Saponification Oil Values for Soap Making SAP value SAP value No. Name of Oil for NaOH for KOH 1 Abyssinian Oil 0.12 0.168 2 Almond Butter 0.134 0.188 3 Almond Oil 0.139 0.195 4 Aloe Butter 0.171 0.24 5 Andiroba Oil 0.134 0.188 6 Apricot Kernal Oil 0.139 0.195 7 Argan Oil 0.136 0.191 8 Avocado Butter 0.133 0.187 9 Avocado Oil 0.133 0.186 10 Babassu Oil 0.175 0.245 11 Baobab Oil 0.143 0.2 12 Beeswax 0.067 0.094 13 Black Cumin Seed Oil 0.139 0.195 14 Black Currant Seed Oil 0.135 0.19 15 Borage Oil 0.135 0.19 16 Brazil Nut Oil 0.135 0.19 17 Broccoli Seed Oil 0.123 0.172 18 Buriti Oil 0.159 0.223 19 Camelina Seed Oil 0.134 0.188 20 Candelila Wax 0.031 0.044 21 Canola Oil 0.133 0.186 22 Carrot Seed Oil 0.103 0.144 23 Castor Oil 0.128 0.18 24 Cherry Kernal Oil 0.135 0.19 25 Chicken Fat 0.139 0.195 26 Cocoa Butter 0.138 0.194 27 Coconut Oil 0.183 0.257 28 Coconut Oil, fractionated 0.232 0.325 29 Coffee Been Oil, green 0.132 0.185 30 Coffee Bean Oil, roasted 0.128 0.18 31 Cohune Oil 0.146 0.205 32 Corn Oil 0.137 0.192 33 Cotton Seed Oil 0.138 0.194 34 Cranberry Seed Oil 0.135 0.19 35 Crisco 0.138 0.193 36 Cupuacu Oil 0.137 0.192 37 Duck Fat 0.138 0.194 38 Emu Oil 0.135 0.19 39 Evening Primrose Oil 0.135 0.19 Crafter's Community Member Page 1 Lesson 1 Part 5 Thermal Mermaid SAP Chart SAP value SAP value No. -

Belize (British Honduras): Odd Man Out, a Geo-Political Dispute" (1976)

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1976 Belize (British Honduras): Odd Man Out, a Geo- Political Dispute Gustave D. Damann Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Geography at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Damann, Gustave D., "Belize (British Honduras): Odd Man Out, a Geo-Political Dispute" (1976). Masters Theses. 3424. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3424 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BELIZE (BRITISH HONDURAS): ODD MAN OUT A GEO-POLITICAL DISPUTE (TITLE) BY Gustave D. Damann - - THESIS SUBMIITTD IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF M.S. in Geography IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS 1976 YEAR I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS THESIS BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE GRADUATE DEGREE CITED ABOVE May 13, 1976 DATE ADVISER May 13, 1976 DATE DEPARTMENT HEAD PAPER CERTIFICATE #2 TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. I The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. -

Pioneers of Belmopan’

This publication was designed by Ms. Tiffany Taylor, UB Social Work student, and printed by the National Council on Ageing. July 2009 The National Council on Ageing Unit 17, Garden City Plaza Mountain View Boulevard P.O. Box 372 Belmopan City Belize Central America Telephone: + 501-822-1546 Fax/ Message: + 501-822-3978 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ncabz.org TABLE OF CONTENTS The National Council on Ageing continually seeks to raise awareness of the important role of older people in Belizean society. Forward ...…………………………………………………3 Through the collaboration with Ms. Tiffany Taylor, History of Belmopan ..……………….….….……………..4 University of Belize, Associates Degree, Social Work Mr. .Justo Castillo …..……………………...….………….6 student, the NCA was able to highlight the contribution of just some of the older people who played a part in laying the Mrs. Gwendolyn Zetina ……………………………………8 foundations of Belmopan. Mrs. Patricia Robinson …………………………………10 Mrs. Leonie Cain …..…………………………………….11 The people in this booklet, along with so many others too Ms. Juanita Ireland ………… ………………………… 12 numerous to mention, are truly all ‘Pioneers of Belmopan’. Mr. Orlando Orio .……………………….………..……...13 The National Council on Ageing congratulates Tiffany for Mrs. Justa Arzu .….……………………………………. 14 the production of this booklet and for successfully Mr. Edred and Mrs. Alma Dakers …..…....…….…...……15 completing her Social Work Degree. Mrs. Catharine Gill ..……………………………………..17 Thank You .……………………………………………....19 Acknowledgement . ……………………………………..20 Page 2 Page 19 pecial thanks to all the people S who agreed to be interviewed FORWARD and share their memories with me, without them this booklet wouldn’t have been possible. MAIN HEADING The foundation of our country was built on the production and ambitions of our ancestors and present generation should Thanks to the Belize Archives preserve and admire the fruits of their labors, and therefore Department for providing me with keep their stories alive and fresh in the minds of our youths. -

The Belize Ag Report Belize’S Most Complete Independent Agricultural Publication

The Belize Ag Report Belize’s most complete independent agricultural publication pg. 16 NOV 2013 - JAN 2014 BGGA on Corn pg. 17 ISSUE 23 Thiessen Liquid Fertilizer Rice Field Day Pg. 12 Field Margins pg. 18 Mamey Sapote pg. 22 Syngenta.com Panela pg. 21 Citrus Industry pg. 5 Cohune Stove pg. 3 57 ac Farm 668-0749 / 663-6777 holdfastbelize.com US$ 275 K FARM LISTINGS Home with Pool See pg. 2 & 26 www.brandbelize.com NOV 2013 - JAN 2014 BelizeAgReport.com 1 Harvesting Ag News from All of Belize Land is our language TM We speak farm land and river land We are involved in agriculture so we are familiar with local issues and understand agricultural concerns. We have buyers/renters for farmland. Let us know if have land to sell or rent. S L As a small company, we personalize our service to both buyer and seller. Court Roberson•Beth Roberson 668-0749 / 663-6777 www.holdfastbelize.com Belize Spice Farm && Botanical Gardens Come and visit the largest Vanilla & Black Pepper farm in Belize!!! Come enjoy our tropical plant collection which in addition to Vanilla and Black Pepper, includes Cardamom, Clove, Nutmeg, Cashew, Rambuttan, Sapote, Anjili, Bilimbi, Carambola, Nellipuli, Jackfruit, Mangos, Jatropha and many flowering plants too many to list! Tours are open to the public!!! Nursery plants on sale til end of Chocolate Festival May 26th Golden Stream, Southern Highway, Toledo District 221 km, or approximately 3 hours drive from Belize City (501) 732 - 4014 • [email protected] www.belizespicefarm.com NOV 2013 - JAN 2014 BelizeAgReport.com 2 Harvesting Ag News from All of Belize Belize’s ‘Green Coal’: cohune nuts. -

Rassegna Stampa Break Dance 2019

RASSEGNA STAMPA Attività 2018-2019 Aggiornata al 7 aprile 15-FEB-2019 da pag. 43 Dir. Resp.: Andrea Monti foglio 1 / 2 www.datastampa.it Tiratura: 270079 - Diffusione: 199220 - Lettori: 3179000: da enti certificatori o autocertificati Superficie 73 % 116 15-FEB-2019 da pag. 43 Dir. Resp.: Andrea Monti foglio 2 / 2 www.datastampa.it Tiratura: 270079 - Diffusione: 199220 - Lettori: 3179000: da enti certificatori o autocertificati Superficie 73 % 116 Arriva la danza ai Giochi: Parigi 2024 con la breakdance 20 febbraio 2019 Dopo il surf, il climbing (arrampicata) e lo skateboard, tocca alla danza sportiva (probabile sia la breakdance) entrare a fare parte dei Giochi olimpici: succederà a Parigi nel 2024, proprio quella Olimpiade che sognava Malagò per Roma. Domani, giovedì 21 febbraio, il comitato olimpico francese annuncerà a Parigi quali saranno le discipline che faranno parte dei Giochi estivi. Rispetto a Tokyo 2020, usciranno quasi sicuramente baseball &softball e karate (dove pure i francesi sono forti). Si "salveranno" surf, arrampicata e skateboard, che entreranno a fare parte per la prima volta dei Giochi olimpici giapponesi fra un anno. Ma farà il suo ingresso per la prima volta in maniera ufficiale alle Olimpiadi di Parigi la danza sportiva, disciplina praticatissima anche in Italia dove c'è una Federazione forte (Fids), con oltre centomila iscritti e che adesso, col presidente Barbone, pare aver trovato un periodo di tranquillità dopo anni assai travagliati. Le discipline riconosciute dal Coni nel vasto panorama agonistico della danza sportiva sono ben 54, articolate tra i settori delle danze artistiche (Accademiche, Coreografiche, Street e Pop Dance, Etniche, Popolari e di Carattere) e delle danze di coppia (Internazionali - tra cui Standard, Latine, Jazz, Caraibiche, Argentine e Afrolatine - Nazionali e Regionali).