The Soap Making Companion a Guide for Beginners 2Nd Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Essential Wholesale & Labs Carrier Oils Chart

Essential Wholesale & Labs Carrier Oils Chart This chart is based off of the virgin, unrefined versions of each carrier where applicable, depending on our website catalog. The information provided may vary depending on the carrier's source and processing and is meant for educational purposes only. Viscosity Absorbtion Comparible Subsitutions Carrier Oil/Butter Color (at room Odor Details/Attributes Rate (Based on Viscosity & Absorbotion Rate) temperature) Description: Stable vegetable butter with a neutral odor. High content of monounsaturated oleic acid and relatively high content of natural antioxidants. Offers good oxidative stability, excellent Almond Butter White to pale yellow Soft Solid Fat Neutral Odor Average cold weather stability, contains occlusive properties, and can act as a moistening agent. Aloe Butter, Illipe Butter Fatty Acid Compositon: Palmitic, Stearic, Oleic, and Linoleic Description: Made from Aloe Vera and Coconut Oil. Can be used as an emollient and contains antioxidant properties. It's high fluidiy gives it good spreadability, and it can quickly hydrate while Aloe Butter White Soft Semi-Solid Fat Neutral Odor Average being both cooling and soothing. Fatty Acid Almond Butter, Illipe Butter Compostion: Linoleic, Oleic, Palmitic, Stearic Description: Made from by combinging Aloe Vera Powder with quality soybean oil to create a Apricot Kernel Oil, Broccoli Seed Oil, Camellia Seed Oil, Evening Aloe Vera Oil Clear, off-white to yellow Free Flowing Liquid Oil Mild musky odor Fast soothing and nourishing carrier oil. Fatty Acid Primrose Oil, Grapeseed Oil, Meadowfoam Seed Oil, Safflower Compostion: Linoleic, Oleic, Palmitic, Stearic Oil, Strawberry Seed Oil Description: This oil is similar in weight to human sebum, making it extremely nouirshing to the skin. -

Petition to the Administrative Council of the European Patent Organization

August 10, 2019 BY EMAIL Petition to the Administrative Council of the European Patent Organization Cc: Antonio Campinos, President of the EPO Emmanuel Macron, President, French Republic Christoph Ernst, VP Legal/ International Affairs Angela Merkel, Chancellor, Germany Karin Seegert, COO, Healthcare & Chemistry Mark Rutte, Prime Minister, The Netherlands Piotr Wierzejewski, Quality Management Boris Johnson, Prime Minister, United Kingdom Stoyan Radkov - Applicant’s Representative Cornelia Rudloff-Schäffer, President, German PTO Tim Moss, CEO, Intellectual Property Office of Cadre Philippe, Director, French National Institute the United Kingdom of Industrial Property Vincentia Rosen-Sandiford, Director, Netherlands Patent Office Re: European patent application 09735962.4; and European divisional application 17182663.9; Applicant: Asha Nutrition Sciences, Inc. Dear Delegates in the Administrative Council, We have been prosecuting the referenced patent applications directed to critical innovations for public health at EPO for last 10 years. However, rather than advancing the innovations EPO has been obstructing them. EPO statements in the prosecution history evidence that rejections have been applied to oblige us to reduce the claimed scope, even though as per provisions of European Patent Convention, the subject claims are perfectly patentable. A narrow patent is not synonymous with a quality patent. The metric of quality disregarded by EPO is genuine innovation, measured by betterment of life achieved, though that is the very purpose of patents and is built into the law. For example, solutions to critical unmet needs are inventive even if claims are otherwise obvious (GL1, G-VII, 10.3). Narrow patents in the nutrition arts have already caused great harm to public health and created patent-practice- made humanitarian crises by creating misinformation and taken us farther away from solving nutritional problems, preventative solutions, and sustainability. -

Watermelon Seed Oil: Its Extraction, Analytical Studies, Modification and Utilization in Cosmetic Industries

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 07 Issue: 02 | Feb 2020 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 Watermelon Seed Oil: Its Extraction, Analytical studies, Modification and Utilization in Cosmetic Industries Sarfaraz Athar1, Abullais Ghazi2, Osh Chourasiya3, Dr. Vijay Y. Karadbhajne4 1,2,3Department of Oil Technology, Laxminarayan Institute of Technology, Nagpur 4Head, Dept. of Oil Technology, Professor, Laxminarayan Institute of Technology, Nagpur, Maharashtra, India ---------------------------------------------------------------------***--------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract - Watermelon seed is one of the unexplored seed in acid or omega 6 fatty acid (about 45-73%). Oleic, palmitic the world which is often discarded after eating the fruit. and stearic acid are also present in small quantities [3]. Researches show that these seeds contain nutrients like protein, essential fatty acids, vitamins and minerals. Oil Various researches report the positive effect of watermelon content in the seeds is between 35-40% and the unsaturated seed oil over skin. The oil is light, consists of humectants and fatty acid content in oil is 78-86% predominantly linoleic acid moisturising properties. It is easily absorbed by skin and (45-73%). This oil is effective for skin care as it is light, easily helps in restoring the elasticity of skin. Due to these absorbable and has humectants properties. Our study is about attributes this oil can be used in cosmetic industry for extraction of watermelon seed oil by solvent extraction process production of skin care products. The watermelon seed oil with the use of different solvents, its analysis and application can also be used as an anti inflammatory agent [4]. -

Personal Cleansing Composition Comprising Highly Nourishing Oils

(19) & (11) EP 2 455 063 A1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 23.05.2012 Bulletin 2012/21 A61K 8/44 (2006.01) A61K 8/46 (2006.01) A61K 8/81 (2006.01) A61K 8/92 (2006.01) (2006.01) (2006.01) (21) Application number: 10191786.2 A61Q 5/12 A61Q 19/10 (22) Date of filing: 18.11.2010 (84) Designated Contracting States: • Begoin-Petreins, Britta AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB 33034 Brakel (DE) GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO • Böll, Liz PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR 67278 Bockenheim (DE) Designated Extension States: • Lähn, Natascha BA ME 67591 Offstein (DE) • Schimmele, Stefan (71) Applicant: Dalli-Werke GmbH & Co. KG 68782 Brühl (DE) 52224 Stolberg (DE) • Nadeem, Zia Ullah 55232 Alzey (DE) (72) Inventors: • Bastian, Christin (74) Representative: Polypatent 55246 Mainz-Kostheim (DE) Braunsberger Feld 29 • Betsch, Roland 51429 Bergisch Gladbach (DE) 67269 Grünstadt (DE) (54) Personal cleansing composition comprising highly nourishing oils (57) The invention relates to an aqueous personal olive oil, coconut oil, and/or sunflower oil; (c) a surfactant cleansing composition, preferably a shower gel, compris- system comprising: (i) an anionic surfactant and (ii) an ing: (a) a nourishing oil component selected from marula amphoteric and/or zwitterionic surfactant; and (d) hydro- oil, apricot kernel oil, argan oil, and/or tamanu oil; (b) a phobically modified crosslinked acrylic copolymer. compatibilizing oil component selected from soybean oil, EP 2 455 063 A1 Printed by Jouve, 75001 PARIS (FR) EP 2 455 063 A1 Description [0001] The present invention relates to personal cleansing compositions, preferably shower gels, comprising at least one nourishing oil selected from marula oil, apricot kernel oil, argan oil and tamanu oil. -

Natural, Vegan & Gluten-Free

Natural, Vegan & Gluten-Free All FarmHouse Fresh® products are Paraben and Sulfate free, made with up to 99.6% natural ingredients and made in Texas. Many of our products are also Vegan and Gluten-Free! Ingredient Decks Honey Heel Glaze: Water/Eau, Glycerine, Polysorbate 20, Polyquaternium-37, Parfum, Honey, Natural Rice Bran Oil (Orza Sativa), Tocopheryl Acetate (Vitamin E),Tetrahexyldecyl Ascorbate, Panthenol, Carica Papaya (Papaya) Fruit Extract, Ananas Sativus (Pineapple) Fruit Extract, Aloe Barbadensis Leaf Juice, Lactic Acid, PEG-40 Hydrogenated Castor Oil, Potassium Sorbate, Diazolidinyl Urea, DMDM Hydantoin, Caramel, Annatto. Strawberry Smash: Aloe Barbadensis Leaf Juice, Water/Eau, Glycerin, Glycine Soja (Soybean) Oil, Polysorbate 80, Butyrospermum Parkii (Shea Butter), Cetearyl Alcohol, Ceteareth-20, Cetyl Alcohol, Stearyl Alcohol, Parfum, Fragaria Vesca (Strawberry) Fruit Extract, Oryza Sativa (Rice) Barn Oil, Ethylhexyl Palmitate, Dimethicone, Cyanocobalmin (Vitamin B12), Tocopheryl Acetate, Menthone Glycerin Acetal, Carbomer, Disodium EDTA, Tetrasodium EDTA, Sodium Hydroxymethylglycinate, Sodium Hydroxide, Phenoxyethanol, Caprylyl Glycol, Potassium Sorbate Sweet Cream Body Milk: Water/Eau, Glycine Soja (Soybean) Oil, Sorbitol, Glycerin, Glyceryl Stearate, PEG-100 Stearate, Cetyl Alcohol, Oryza Sativa (Rice) Bran Oil, Simmondsia Chinensis (Jojoba) Seed Oil, Prunus Amygdalus Dulcis (Sweet Almond) Oil, Persea Gratissima (Avocado) Oil, Sesamum Indicum (Sesame) Seed Oil, Stearyl Alcohol, Dimethicone, Polysorbate 20, Carbomer, -

KALAHARI MELON SEED Cold Pressed

Tel: +27(0)83 303 8253 ADDRESS: Vlakbult Tel: +27(0)827893035 PO Box 35 Clocolan [email protected] 9735 South Africa KALAHARI MELON SEED Cold pressed oil LATIN NAME: Citrullus lanatus INCI NAME: Citrullus lanatus (watermelon) seed oil OTHER NAMES: Karkoer, Mankataan, Tshamma, Ootanga White Watermelon, Wild Melon, Wild Watermelon CAS Nr: 90063-94-8 SOURCE: Cold pressed from the seed. COLOUR Colourless to very light yellow-green colour AROMA Very subtle neutral odour CULTIVATION: Commercially grown ORIGEN: South Africa It is the biological ancestor of the watermelon, which is now found all over the world, but which originated in the Kalahari region of Southern Africa. Unlike the common watermelon, whose flesh is sweet and red, the Kalahari melon’s flesh is pale yellow or green, and tastes OVERVIEW bitter. It is a creeping annual herb. The Kalahari melon has hairy stems, forked tendrils and three-lobed hairy leaves. Its flowers are bright yellow. The fruits vary significantly, from small and round in the wild, to larger and more oblong- shaped under cultivation. The surface is smooth, pale green with irregular bands of mottled darker green radiating from the stalk. The flesh is a pale green or yellow, and contains numerous brown seeds. In its wild form, the fruit is bitter to bland in taste, and largely inedible when fresh. The Kalahari melon or edible tsamma is ‘sweet' and highly adapted to surviving drought and the harsh light of the desert environment. Although found all over Southern Africa, it is most closely associated with the Kalahari sands of Namibia, Botswana, south-western Zambia and Bushmans eating Kalahari western Zimbabwe. -

379 Skin Colonizer(Rebalance the Skin Microbiome)

379_SkinColonizer_Package_v1.pdf 1 2/15/17 3:12 PM #379 Skin Colonizer (Rebalance The Skin Microbiome) The Leader in Cellular Nutrition #379 Skin Colonizer (Rebalance The Skin Microbiome) The bacteria that inhabit human skin are found to serve hundreds, if not thousands, of beneficial activities including help with healing wounds, informing cell receptors to initiate cellular activities, and serving as a front-line immune system that provides protection and immune modulation regarding the myriad of pathogens that seek entrance to the body. Skin Colonizer is an innovative breakthrough in product formulation by presenting the body with truly viable cultures. t INDICATIONS • Kukui Oil - A natural moisturizer used by the Hawaiians for hundreds of years, and is touted to support normal wound • Support normal skin microbiome healing. A rich source of antioxidants. • Skin comfort regarding occasional rashes • Marula Oil - A source of Omega-6 and Omega-9 fatty • Skin comfort regarding occasional itches acids famous for nourishing the skin. Cited to help normal ™ tSupplement INGREDIENTS Facts Servings per container: About 30 • Occasional diaper rash comfort preservation of transepidermal water migration—thus an Serving size: 1 mL excellent moisturizer. Skin Microbiome Calories 8.1 • Comfort regarding exanthems Amount per serving % Daily Value • Perilla Oil - Contains a special, essential fatty acid, n-3 linolenic colonizer provides a Total Fat 0.9 g 1% • Support normal gut-skin-brain microbial axis Vitamin E (d-alpha-Tocopheryl Acetate) 9 IU 30% acid that plays a major role in regulating normal inflammation C unique combination of Vitamin D 250 IU 63% • Support of skin microbiome species diversity processes in the skin. -

Effect of Process Parameters on the Physical Properties of Watermelon Seed Oil Under Uniaxial Compression

Nutrition & Food Science International Journal ISSN 2474-767X Research Article Nutri Food Sci Int J - Volume 4 Issue 1 November 2017 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Nwosu Caesar DOI: 10.19080/NFSIJ.2017.04.555626 Effect of Process Parameters on the Physical Properties of Watermelon Seed Oil under Uniaxial Compression Nwosu Caesar1*, Ozumba Isaac C1 and Kabir Abdullahi O2 1Agro-Industrial Development and Extension Department, National Centre for Agricultural Mechanization, Nigeria 2Agricultural and Bio systems Engineering Department, University of Ilorin, Nigeria Submission: May 01, 2017; Published: November 17, 2017 *Corresponding author: Nwosu Caesar, Agro-Industrial Development and Extension Department, National Centre for Agricultural Mechanization, Nigeria, Email: Abstract The effect of process parameters such as temperature and pressure on the physical properties of watermelon seed oil under uniaxial compression was studied. A laboratory mechanical oil expression piston-cylinder rig was used to express oil from watermelon seeds at different temperatures (100 °C, 110 °C, 120 °C and 130 °C) and different pressures (5000Kg, 5500Kg, 6000Kg and 6500Kg). The expressed oil was analyzed analysis using Analysis of variance (ANOVA). for Viscosity, Specific gravity, Refractive Index and Boiling Point using standard methods. The results obtained were subjected to statistical The results revealed that viscosity of the expressed oil consistently decreased with increase in heating temperature for all the pressure regimes under study and increased with increasing applied pressure for all temperature regimes under study. The results also showed that wasprocess also conditions revealed in did this not study affect that the while specific increasing gravity temperatureof the expressed reduces oil in Boiling a particular point, increasingpattern. -

Niop Trading Rules

NIOP TRADING RULES Effective July 2013 Minor changes and corrections (approved by the NIOP Technical Committee) have been included as of July 29, 2013 APPLICATION OF RULES INCORPORATION OF THESE RULES OR ANY PORTION THEREOF IS NOT MANDATORY BUT IS OPTIONAL BETWEEN PARTIES TO CONTRACTS. Published by the National Institute of Oilseed Products 750 National Press Building, 529 14th St NW Washington, D.C. 20045 TEL: (202) 591-2438 FAX: (202) 591-2445 e-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.niop.org ©2013 by the National Institute of Oilseed Products NIOP TRADING RULES TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 - TYPES OF SALES RULE 1.1 TRADE PRACTICE 1 -1 1.2 PLACE OF CONTRACT 1 -1 1.3 C.I.F. (COST, INSURANCE AND FREIGHT) 1 -1 LISTING OF DOCUMENTS 1 -2 1.4 C.& F. (COST AND FREIGHT) 1 -3 1.5 F.O.B. VESSEL (FREE ON BOARD VESSEL) 1 -3 1.6 F.A.S. VESSEL (FREE ALONGSIDE) -NAMED PORT OF SHIPMENT 1 -5 1.7 EX DOCK (NAMED PORT OF IMPORTATION) 1 -6 1.8 EX WAREHOUSE 1 -7 1.9 MISCELLANEOUS TYPES OF SALES 1 -7 1.10 VESSEL CLASSIFICATION 1 -7 1.11 PUBLIC HEALTH SECURITY AND BIOTERRORISM PREPAREDNESS 1 -7 CHAPTER 2 - SHIPMENT RULE 2.1 TIME 2 -1 2.2 DAYS OR HOURS 2 -1 2.3 NOTICE 2 -1 2.4 TENDERS 2 -1 2.5 EXTENSION OF SHIPMENT 2 -1 2.6 PROOF OF ORIGIN 2 -3 2.7 TRANSHIPMENT 2 -3 2.8 SHIPPING INSTRUCTIONS 2 -3 2.9 VESSEL NOMINATION AND DECLARATION OF DESTINATION 2 -3 2.10 BILL OF LADING-EVIDENCE OF DATE OF SHIPMENT 2 -3 CHAPTER 3 - TANK CARS, TRUCKS, BARGES AND CONTAINERS RULE 3.1 DATE OF SHIPMENT 3 -1 3.2 TIME OF SHIPMENT 3 -1 3.3 SPREAD (SCATTERED) DELIVERIES OF SHIPMENTS 3 -1 3.4 F.O.B. -

Date Seeds: a Promising Source of Oil with Functional Properties

foods Review Date Seeds: A Promising Source of Oil with Functional Properties Abdessalem Mrabet 1,2, Ana Jiménez-Araujo 1,* , Rafael Guillén-Bejarano 1 , Rocío Rodríguez-Arcos 1 and Marianne Sindic 2 1 Instituto de la Grasa, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), Campus Universitario Pablo de Olavide, Edificio 46, Ctra. de Utrera, 41013 Seville, Spain; [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (R.G.-B.); [email protected] (R.R.-A.) 2 Department Agro-Bio-Chem, University of Liege—Gembloux Agro-Bio Tech, Passage des Déportés 2, 5030 Gembloux, Belgium; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 May 2020; Accepted: 11 June 2020; Published: 16 June 2020 Abstract: The cultivation of the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) is the main activity and source of livelihood for people from arid and semiarid regions of the world. Date production is increasing every year. In addition, pitted date exportation is rising and great amounts of date seeds are produced. This biomass represents a problem for manufacturing companies. At the moment, date seeds are normally discarded or used as animal feed ingredients. However, this co-product can be used for many other applications due to its valuable chemical composition. Oil is one of the most interesting components of the date seed. In fact, date seeds contain 5–13% oil. Date seed oil contains saturated and unsaturated fatty acids with lauric and oleic as the main ones, respectively. Tocopherols, tocotrienols, phytosterols, and phenolic compounds are also present in significant amounts. These phytochemicals confer added value to date seed oil, which could be used for many applications, such as food product formulations, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals. -

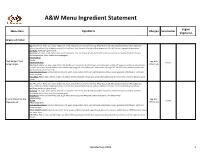

Menu Ingredient Statement

A&W Menu Ingredient Statement Vegan/ Menu Item Ingredients Allergen Sensitivities Vegetarian Burgers and Chicken Bun: Wheat Flour, Water, Corn Syrup, Soybean Oil, Yeast, Contains 2% or less of the following: Wheat Gluten, Salt, Malt, Dough Conditioners (Monoglycerides, Sodium Stearoyl Lactylate, Azodicarbonamide), Artificial Flavor, Yeast Nutrients (Calcium Sulfate, Ammonium Chloride), Calcium Propionate (Preservative). Beef Patty: Hamburger (ground beef). Seasoning: Salt, sugar, spices, paprika, dextrose, onion powder, corn starch, garlic powder, hydrolyzed cornprotein, extractive of paprika, disodium inosinate, disodium guanylate, silicon dioxide (anti-caking agent). Iceberg Lettuce Tomato Papa Burger/ Papa Egg, Milk, Yellow Onion Slices Gluten Burger Single Papa Sauce: Soybean oil, water, sugar, pickle relish (pickles, corn sweeteners, distilled vinegar, salt, xanthan gum, alum 0.10% potassium sorbate as a preservative, Wheat, Soy turmeric, natural spice flavors), tomato paste, distilled vinegar, egg yolk, salt, xanthan gum, artificial color including FD&C Red #40, spices, oleoresin paprika, Beta Apo-8-Carotenal, natural flavorings. Sharp American Cheese: Cultured milk and skim milk, water, cream, sodium citrate, salt, sorbic acid (preservative), sodium phosphate, artificial color, acetic acid, lecithin, enzymes. Pickle Slices: Pickles, water, distilled vinegar, salt, calcium chloride, potassium sorbate (as a preservative), polysorbate 80, natural flavors, turmeric oleoresin, garlic powder. Bun: Wheat Flour, Water, Corn Syrup, Soybean Oil, Yeast, Contains 2% or less of the following: Wheat Gluten, Salt, Malt, Dough Conditioners (Monoglycerides, Sodium Stearoyl Lactylate, Azodicarbonamide), Artificial Flavor, Yeast Nutrients (Calcium Sulfate, Ammonium Chloride), Calcium Propionate (Preservative). Beef Patty: Hamburger (ground beef). Seasoning: Salt, sugar, spices, paprika, dextrose, onion powder, corn starch, garlic powder, hydrolyzed cornprotein, extractive of paprika, disodium inosinate, disodium guanylate, silicon dioxide (anti-caking agent). -

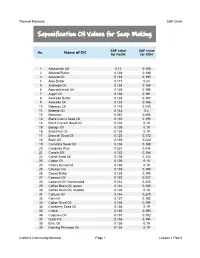

Saponification Oil Values for Soap Making

Thermal Mermaid SAP Chart Saponification Oil Values for Soap Making SAP value SAP value No. Name of Oil for NaOH for KOH 1 Abyssinian Oil 0.12 0.168 2 Almond Butter 0.134 0.188 3 Almond Oil 0.139 0.195 4 Aloe Butter 0.171 0.24 5 Andiroba Oil 0.134 0.188 6 Apricot Kernal Oil 0.139 0.195 7 Argan Oil 0.136 0.191 8 Avocado Butter 0.133 0.187 9 Avocado Oil 0.133 0.186 10 Babassu Oil 0.175 0.245 11 Baobab Oil 0.143 0.2 12 Beeswax 0.067 0.094 13 Black Cumin Seed Oil 0.139 0.195 14 Black Currant Seed Oil 0.135 0.19 15 Borage Oil 0.135 0.19 16 Brazil Nut Oil 0.135 0.19 17 Broccoli Seed Oil 0.123 0.172 18 Buriti Oil 0.159 0.223 19 Camelina Seed Oil 0.134 0.188 20 Candelila Wax 0.031 0.044 21 Canola Oil 0.133 0.186 22 Carrot Seed Oil 0.103 0.144 23 Castor Oil 0.128 0.18 24 Cherry Kernal Oil 0.135 0.19 25 Chicken Fat 0.139 0.195 26 Cocoa Butter 0.138 0.194 27 Coconut Oil 0.183 0.257 28 Coconut Oil, fractionated 0.232 0.325 29 Coffee Been Oil, green 0.132 0.185 30 Coffee Bean Oil, roasted 0.128 0.18 31 Cohune Oil 0.146 0.205 32 Corn Oil 0.137 0.192 33 Cotton Seed Oil 0.138 0.194 34 Cranberry Seed Oil 0.135 0.19 35 Crisco 0.138 0.193 36 Cupuacu Oil 0.137 0.192 37 Duck Fat 0.138 0.194 38 Emu Oil 0.135 0.19 39 Evening Primrose Oil 0.135 0.19 Crafter's Community Member Page 1 Lesson 1 Part 5 Thermal Mermaid SAP Chart SAP value SAP value No.