Military Law Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Improving the Total Force Using National Guard and Reserves

IMPROVING THE TOTAL FORCE USING THE NATIONAL GUARD AND RESERVES A Report for the transition to the new administration by The Reserve Forces Policy Board RFPB Report FY17-01 This report, Report FY17-01, is a product of the Reserve Forces Policy Board. The Reserve Forces Policy Board is, by law, a federal advisory committee within the Office of the Secretary of Defense. As mandated by Congress, it serves as an independent adviser to provide advice and recommendations directly to the Secretary of Defense on strategies, policies, and practices designed to improve and enhance the capabilities, efficiency, and effectiveness of the reserve components. The content and recommendations contained herein do not necessarily represent the official position of the Department of Defense. As required by the Federal Advisory Committee Act of 1972, Title 5, and the Code of Federal Regulations, Title 41, Section 102-3 (Federal Advisory Committee Management), this report and its contents were deliberated and approved in several open, public sessions. IMPROVING THE TOTAL FORCE USING THE NATIONAL GUARD AND RESERVES A Report for the transition to the new administration by The Reserve Forces Policy Board RFPB Report FY17-01 4 5 6 Chairman Punaro introduces the Secretary of Defense, the Honorable Ashton B. Carter, during the June 9, 2015 Board Meeting. “The presence, skill and readiness of Citizen Warriors across the country give us the agility and flexibility to handle unexpected demands, both at home and abroad. It is an essential component of our total force, and a linchpin of our readiness.” 1 - Secretary of Defense Ash Carter 1 As Delivered by Secretary of Defense Ash Carter, Pentagon Auditorium, Aug. -

Title 35 Public Health and Safety

TITLE 35 - PUBLIC HEALTH AND SAFETY CHAPTER 1 - ADMINISTRATION ARTICLE 1 - IN GENERAL 35-1-101. Local contributions; disposition. All monies paid to the state treasurer representing contributions by city councils, county commissioners, trustees of school districts, or other public agencies, for public health purposes, shall be set up and designated on the books of the state treasurer in a separate account, and shall be expended and disbursed upon warrants drawn by the state auditor against said account when the vouchers therefor have been approved by the department of health. 35-1-102. Sanitation of public institutions. It shall be the duty of the officers, managers, superintendents, proprietors and lessees of all hospitals, asylums, infirmaries, prisons, jails, schools, theaters, public places and public institutions to remedy any and all defects relating to the unsanitary condition of such institution, or institutions, as may be under their control, when such defects shall have been called to their attention in writing by the department of health. 35-1-103. Neglect or failure of officials to perform duty. Any member of the department of health, any county health officer, or any officer, superintendent, or principal of any city, town, county or institution named in this act, who shall fail or neglect to perform any of the duties herein required of them, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and upon conviction thereof shall be fined in the sum of not less than one hundred dollars ($100.00) nor more than one thousand dollars ($1,000.00), or shall be confined in the county jail for a period of not less than six (6) months, nor more than a year, or both. -

Fiscal Year 2020 Legislative Resolutions 2 Legislative Resolutions

FISCAL YEAR 2020 LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTIONS 2 LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTIONS // www.ngaus.org CONTENTS www.ngaus.org // LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTIONS 3 4. A Letter from Our Chairman 24. Air Resolutions 6. About NGAUS 56. Joint Resolutions 8. NGAUS Legislative Team 92. NGAUS Board of Directors 10. The Guard in the Federal Budget 94. NGAUS Areas 12. Resolutions Timeline 96. Area Directors 14. Army Resolutions 98. NGAUS Staff 4 LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTIONS // www.ngaus.org A LETTER FROM OUR CHAIRMAN www.ngaus.org // LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTIONS 5 It is my privilege to present the Fiscal Year 2020 Legislative Resolutions of the National Guard Association of the United States (NGAUS) on behalf of our nearly 45,000 members. Our mission to advocate for the National Guard in Congress has not changed since our formation in 1878. However, the National Guard and NGAUS’ priorities change as the global threat environment changes. The National Guard is essential to the defense of our nation now, more than ever, as homeland defense and great power competition return to the forefront of the National Defense Strategy. Secretary of Defense James N. Mattis said during this year’s NGAUS General Conference and Exhibition in New Orleans, “Everything we do must contribute to increased lethality. So we need you, my fine young National Guardsmen, at the top of your game. Lethality begins when we are physically, mentally, and spiritually fit to be evaluated by the most exacting auditor on earth. And that auditor is war.” Enhanced lethality means maximum readiness. National Guard readiness includes current and proportional fielding of new equipment and weapons platforms to units that are in line with Army and Air Force requirements, legacy platform modernization and recapitalization to ensure safety and reliability, as well Major General as accessibility to robust health care to ensure continuity of care, and deployability for National Guard Donald Dunbar personnel. -

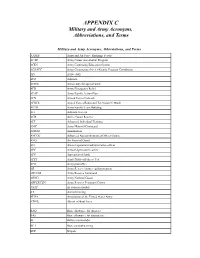

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

Handbook of Legal Terminology Fourth Edition 2020

Handbook of Legal Terminology Fourth Edition 2020 Revised and edited by Randy Pierce Director William Charlton Research Counsel II Carole Murphey Research Counsel II 1 Blank page 2 Preface Reasonable efforts were made to define the words and phrases in this handbook in general terms. However, if the reader desires a precise definition of a term pertaining to a criminal matter or civil action, then please refer to the applicable statute(s) or rule(s). Copyright © 2020, Mississippi Judicial College, University of Mississippi, University, Mississippi 38677 Click a letter, then scroll to term A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z 3 Blank page 4 – A – AB INITIO Latin: “From the beginning.” ABROGATE To annul, cancel or repeal an order or rule. ABSOLUTE IMMUNITY A total exemption from civil liability. ABSTRACT OF RECORD 1. An impartial summary of the most important parts of the pleadings, testimony, exhibits and other matters from the trial court record of a case on appeal. 2. A legally authenticated copy or summary of a lower court’s proceedings, e.g., a justice court’s certified copy of a judgment or conviction. Compare, TRANSCRIPT. ABSTRACT OF TITLE A condensed history of landownership. Compare, DERAIGN. ABUSE OF PROCESS A tort claiming that a legal process or procedure has been used for an improper purpose. ACCESSORY AFTER THE FACT One who assisted a person who has committed a felony from being apprehended, arrested or convicted. ACCESSORY BEFORE THE FACT One who acted or contributed as an assistant or instigator to the commission of a crime. -

2021 May Edition

May 2021 Magazine A YEAR OF RESILIENCE BUILT FROM A CENTURY OF READINESS ROA Adopts Plan to Celebrate Its Centennial By Jennifer Franco n March 13, 2021, the Reserve Organization of America’s governing body unanimously adopted Oa plan to celebrate 100 years of ROA’s supporting our nation’s guard and reserve forces. The plan entails a year-long calendar of events that include in-person and social media engagements to inspire esprit de corps among ROA’s current and potential members and their families. These efforts also aim to give greater visibility to the asso- ciation. The plan includes an event at the Washington, D.C., Willard Hotel, where the ROA was founded during its first convention, October 2-4, 1922. Commencing at ROA’s Memphis National Convention in October this year, specific “lines of effort” will be pro- grammed to take place throughout 2022, culminating in ROA’s first convention at the Willard Hotel in October 1922 Washington, D.C., on October 2. ROA is a congressionally chartered military service organization unique among other military organizations Components,” said ROA’s executive director, retired Army because of its specific focus of support for the Reserve Maj. Gen. Jeffrey E. Phillips. “Supporting the Reserve and Components. The charter states that ROA will “support a Guard is part of what some organizations do; it’s all that military policy that will provide adequate national security ROA does.” and to promote the development and execution thereof.” ROA’s Centennial Celebration plan includes contri- The charter was signed by President Harry S. -

Integrating Active and Reserve Component Staff Organizations: Improving the Chances of Success

C O R P O R A T I O N Integrating Active and Reserve Component Staff Organizations Improving the Chances of Success Laurinda L. Rohn, Agnes Gereben Schaefer, Gregory A. Schumacher, Jennifer Kavanagh, Caroline Baxter, Amy Grace Donohue For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1869 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9828-3 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2019 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Separate active and reserve military organizations have existed since the founding of the nation, and efforts to integrate them more closely—for example, to achieve greater efficiency, to make standards and practices more consistent, or to ensure commonality of purpose—date back to at least 1947. -

Law of Afghanistan

3RD EDITION AN INTRODUCTION TO THE LAW OF AFGHANISTAN An Introduction to the Law of Afghanistan Third Edition Afghanistan Legal Education Project (ALEP) at Stanford Law School http://alep.stanford.edu [email protected] Stanford Law School Crown Quadrangle 559 Nathan Abbott Way Stanford, CA 94305-8610 www.law.stanford.edu ALEP – STANFORD LAW SCHOOL Authors Eli Sugarman (Co-Founder, Student Co-Director, 2007-09) Alexander Benard (Co-Founder, Student Co-Director, 2007-09) Anne Stephens Lloyd (Student Co-Director, 2008-09) Ben Joseloff (Post-Doctoral Fellow at AUAF, 2008) Max Rettig (Student Co-Director, 2009-10) Stephanie Ahmad (Rule of Law Fellow, 2011-12) Jason Berg Editors Morgan Galland (Student Director, 2010-11) Rose Leda Ehler (Student Co-Director, 2011-12) Daniel Lewis (Student Co-Director, 2011-12) Ingrid Price (Student Co-Director, 2012-13) Catherine Baylin Elizabeth Espinosa Jane Farrington Gabriel Ledeen Nicholas Reed Faculty Director Erik Jensen Rule of Law Program Executive Director Megan Karsh Program Advisor Rolando Garcia Miron AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF AFGHANISTAN Contributing Faculty Editors Ghizaal Haress Hamid Khan Haroon Mutasem Chair of the Department of Law Taylor Strickling, 2012-13 Hadley Rose, 2013-14 Mehdi Hakimi, 2014- TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................................................... VI CHAPTER 1: LEGAL HISTORY OF AFGHANISTAN AND THE RULE OF LAW ......... 1 I. INTRODUCTION AND OPENING INQUIRIES .............................................................. -

(AGR) Program Title 32, Full Time National Guard Duty (FTNGD) Management

National Guard Regulation 600-5 Army National Guard The Active Guard Reserve (AGR) Program Title 32, Full Time National Guard Duty (FTNGD) Management National Guard Bureau Arlington, VA 21 September 2015 UNCLASSIFIED SUMMARY OF CHANGE NGR 600-5 The Active Guard Reserve Program Title 32, Full Time National Guard Duty Management 21 September 2015 o Clarifies status and funding requirements for Title 32 Active Guard Reserve Soldiers to travel outside the continental Unites States. Paragraph 3-3 o Clarifies State Mission status for Active Guard Reserve Soldiers. Paragraph 3-4 o Establishes One Time Occasional Tours authority for Title 32 Active Guard Reserve tours. Paragraph 3-6 o Revise guidance pertaining to periods of Convalescent leave. Paragraph 3-8 o Establishes Active Service Obligations for selected military and civilian schools. Paragraph 4- o Updates the Command Leadership and Staff Assignment Policy. Paragraph 4-6 o Clarifies Professor of Military Science and Assistant Professor of Military Science program. Paragraph 4-7 o Establishes an initial tour continuation board process to review and evaluate the records in the third year of their initial tour. Paragraph 5-4 o Establishes career program status for Active Guard Reserve Soldiers continued beyond their initial three year tour. Paragraph 5-1 o Exempts all Active Guard Reserve Soldiers from Qualitative and Selective Retention Boards. Paragraph 5-1 o Added Guidance for Active Guard Reserve Active Service Management Board. Paragraph 5-6 o Established disqualifications that may be waived for entry in the Active Guard Reserve program. Table 2-1 o Established disqualifications that may be waived for subsequent duty in the Active Guard Reserve program. -

Rights and Remedies: Meeting the Civil Legal Needs of Sexual Violence Survivors

The Center for Law & Public Policy on Sexual Violence RIGHTS AND REMEDIES: MEETING THE CIVIL LEGAL NEEDS OF SEXUAL VIOLENCE SURVIVORS A project of The National Crime Victim Law Institute @ Lewis & Clark Law School Jessica E. Mindlin, Esq. Liani Jean Heh Reeves, Esq. CENTER FOR L AW & P UBLIC P OLICY ON SEXUAL VIOLENCE National Crime Victim Law Institute at Lewis & Clark Law School 10015 SW Terwilliger Boulevard Portland, OR 97219 www.ncvli.org Copyright © 2005 National Crime Victim Law Institute. This project was supported by Grant No. 2003-WT-BX-KO13 awarded by the Office on Violence Against Women, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of view in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In 2003, the Center for Law and Public Policy Against Sexual Violence (CLPPS), a project of the National Crime Victim Law Institute (NCVLI) at Lewis & Clark Law School in Portland, Oregon, received a grant from the Office on Violence Against Women (OVW) to assist sexual assault and dual (domestic violence and sexual assault) coalition staff attorneys across the United States. Under the auspices of the OVW grant, the Sexual Assault Coalition Technical Assistance Project (SACTAP) was launched. The OVW grant also funded the development of legal resources for coalitions working on difficult systemic advocacy issues in the civil and criminal justice systems. This guide, Rights and Remedies: Meeting the Civil Legal Needs of Sexual Violence Survivors, is the result of the collaboration of many individuals and organizations that have lent their time and expertise to this project. -

Military Law Review

Volume 158 December 1998 MILITARY LAW REVIEW ARTICLES PLAYING THE NUMBERS: COURT-MARTIAL PANEL SIZE AND THE MILITARY DEATH PENALTY Dwight H. Sullivan THE QUIET REVOLUTION: DOWNSIZING, OUTSOURCING, AND BEST VALUE Major Mary E. Harney THE TWENTY-SECOND EDWARD H. YOUNG LECTURE IN LEGAL EDUCATION: PROFESSIONALISM: RESTORING THE FLAME Colonel Donald L. Burnett, Jr: THE FOURTH ANNUAL HUGH J. CLAUSEN LEADERSHIP LECTURE: SOLDIERING TODAY AND TOMORROW General Frederick M. Franks, Jr: CASE COMMENT THE INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITIES EDUCATION ACT AND DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS: c DDES CASE NO. 97-001 (MARCH 24, 1998) William S. Fields and Carol A. Marchant BOOK REVIEWS ci \o \o 00 Department of Army Pamphlet 27-100-158 MILITARY LAW REVIEW Volume 158 December 1998 ARTICLES Playing the Numbers: Court-Martial Panel Size and the Military Death Penalty Dwight H. Sullivan 1 The Quiet Revolution: Downsizing, Outsourcing, and Best Value Major Mary E. Harney 48 The Twenty-Second Edward H. Young Lecture in Legal Education: Professionalism: Restoring the Flame Colonel Donald L. Burnett, Ji: 109 The Fourth Annual Hugh J. Clausen Leadership Lecture: Soldiering Today and Tomorrow General Frederick M. Franks, Ji: 130 CASE COMMENT The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act and Department of Defense Educational Programs: DDES CASE NO. 97-001 (March 24, 1998) William S. Fields and Carol A. Marchant 147 BOOK REVIEWS The Victors: Eisenhower and His Boys: The Men of World War 11 Reviewed by Major Geofrey S. Corn 159 Warrior Generals: Combat Leadership in the Civil War Reviewed by Major John M. Bickers 164 Prodigal Soldiers: How the Generation of OfJicers Born of Vietnam Revolutionized the American Style of War Reviewed by Major C. -

BY ORDER of the CHIEF NATIONAL GUARD BUREAU AIR NATIONAL GUARD INSTRUCTION 36-2002 1 OCTOBER 2012 Personnel ENLISTMENT and REEN

BY ORDER OF THE AIR NATIONAL GUARD INSTRUCTION CHIEF NATIONAL GUARD BUREAU 36-2002 1 OCTOBER 2012 Personnel ENLISTMENT AND REENLISTMENT IN THE AIR NATIONAL GUARD AND AS A RESERVE OF THE AIR FORCE COMPLIANCE WITH THIS PUBLICATION IS MANDATORY ACCESSIBILITY: Publications and Air Force forms are available for downloading or ordering on the e-Publishing website at www.e-Publishing.af.mil. National Guard Bureau forms are available for downloading or ordering on the NGB Publications & Forms Library website at http://www.ngbpdc.ngb.army.mil/. RELEASABILITY: There are no releasability restrictions on this publication. OPR: NGB/A1PP Certified by: NGB/A1 (Ms. Wanda R. Langley) Supersedes: ANGI36-2002, 1 March 2004 Pages: 152 This instruction implements Air Force Policy Directive (AFPD) 36-20, Accession of Air Force Military Personnel. This instruction prescribes the eligibility requirements and procedures for enlisting and reenlisting in the Air National Guard (ANG) and as a Reserve of the Air Force. Ensure that all records created as a result of processes prescribed in this publication are maintained IAW Air Force Manual (AFMAN) 33-363, Management of Records, and disposed of IAW the Air Force Records Information Management System (AFRIMS) Records Disposition Schedule (RDS) located at https://www.my.af.mil/gcss-af61a/afrims/afrims/. Refer recommended changes and questions about this publication to the Office of Primary Responsibility (OPR) using the AF Form 847, Recommendation for Change of Publication; route AF Form 847s from the field through the appropriate functional’s chain of command. This publication requires the collection and or maintenance of information protected by the Privacy Act of 1974 authorized by 10 United States Code (U.S.C.) and Executive Order (E.O.) 9397 (SSN), as amended by E.O.