Improving the Total Force Using National Guard and Reserves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEPARTMENT of DEFENSE Office of the Secretary, the Pentagon, Washington, DC 20301–1155 Phone, 703–545–6700

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE Office of the Secretary, The Pentagon, Washington, DC 20301–1155 Phone, 703–545–6700. Internet, www.defenselink.mil. SECRETARY OF DEFENSE ROBERT M. GATES DEPUTY SECRETARY OF DEFENSE WILLIAM LYNN III Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, ASHTON B. CARTER Technology, and Logistics Deputy Under Secretary of Defense (Business PAUL A. BRINKLEY Transformation) Deputy Under Secretary of Defense LOUIS W. ARNY III (Installations and Environment) Under Secretary of Defense for Policy MICHELE FLOURNOY Principal Deputy Under Secretary of Defense JAMES N. MILLER, JR. for Policy Assistant Secretary of Defense (International ALEXANDER R. VERSHBOW Security Affairs) Assistant Secretary of Defense (Special MICHAEL VICKERS Operations and Low-Intensity Conflict) Assistant Secretary of Defense (Homeland (VACANCY) Defense and America’s Security) Assistant Secretary of Defense (Global Strategic JOSEPH BENKERT Affairs Assistant Secretary of Defense (Asian and (VACANCY) Pacific Security Affairs) Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense (Plans) JANINE DAVIDSON Deputy Under Secretary of Defense (VACANCY) (Technology Security Policy/Counter Proliferation) Deputy Under Secretary of Defense (Strategy, KATHLEEN HICKS Plans and Forces) Deputy Under Secretary of Defense (Policy PETER VERGA Integration and Chief of Staff) Principal Deputy Under Secretary of Defense WILLIAM J. CARR, Acting for Personnel and Readiness Assistant Secretary of Defense (Reserve Affairs) DAVID L. MCGINNIS, Acting Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense (Reserve JENNIFER C. BUCK Affairs) Deputy Under Secretary of Defense (Program JEANNE FITES Integration) Deputy Under Secretary of Defense (Readiness) SAMUEL D. KLEINMAN Deputy Under Secretary of Defense (Military WILLIAM J. CARR Personnel Policy) Deputy Under Secretary of Defense (Military ARTHUR J. MYERS, Acting Community and Family Policy) Deputy Under Secretary of Defense (Plans) GAIL H. -

The Ohio National Guard Before the Militia Act of 1903

THE OHIO NATIONAL GUARD BEFORE THE MILITIA ACT OF 1903 A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Cyrus Moore August, 2015 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by Cyrus Moore B.S., Ohio University, 2011 M.A., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by Kevin J. Adams, Professor, Ph.D., Department of History Master’s Advisor Kenneth J. Bindas, Professor, Ph.D, Chair, Department of History James L Blank, Ph.D., Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter I. Republican Roots………………………………………………………19 II. A Vulnerable State……………………………………………………..35 III. Riots and Strikes………………………………………………………..64 IV. From Mobilization to Disillusionment………………………………….97 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………….125 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………..136 Introduction The Ohio Militia and National Guard before 1903 The second half of the nineteenth century witnessed a profound change in the militia in the United States. Driven by the rivalry between modern warfare and militia tradition, the role as well as the ideology of the militia institution fitfully progressed beyond its seventeenth century origins. Ohio’s militia, the third largest in the country at the time, strove to modernize while preserving its relevance. Like many states in the early republic, Ohio’s militia started out as a sporadic group of reluctant citizens with little military competency. The War of the Rebellion exposed the serious flaws in the militia system, but also demonstrated why armed citizen-soldiers were necessary to the defense of the state. After the war ended, the militia struggled, but developed into a capable military organization through state-imposed reform. -

How Was the Course of the Revolution Shaped by the People of Paris From

Remember the bourgeoisie were significant in directing the revolution, making up the membership of the National Assembly, the Legislative Assembly & the Convention & the peasants influenced events through their violence e.g. the Great Fear led to the August Decrees which destroyed feudalism in 1789. The Terror gradually moved beyond the Sans Culottes' control as the Committee of Public Safety became more ruthless, seeking more centralised government. Enthusiastic supporters of the Terror found themselves The power of the crowds & the Sans its next victims, e.g. the popular leader, Danton. Culottes was centred on Paris though there were some in the provinces, The revolutionary armies & the popular societies in the sections were disbanded. Why did the influence of the Sans particularly in the revolutionary armies. The law of Maximum was extended to control wages as well as food, despite continuing food shortages. Culottes' wane after 1794? The crowds & Sans Culottes were influential through The crowds & the Sans Culottes their use of Parisian journees to effect change e.g. The Thermidorian Reaction that toppled Robespierre broke their power. were one of a number of through the October Days 1795 saw the arrests of & disarmament of Sans Culottes, the closure of the Jacobin Club & the Paris Commune. influences that shaped the revolution. The Sans Culottes were dominant in the National Guard, the Parisian sections & the revolutionary commune set up in 1792. Some historians think the Terror was the work of a bloodthirsty mob of frustrated men who enjoyed their taste of power and revelled in an orgy of violence Paris was only 12 miles from Versailles so news of Other historians think the Terror was the work of sincere revolutionaries There are 2 opposing views amongst historians the latest political developments always reached trying to clear France of privilege, corruption & the enemies of revolution. -

The Case for Larger Ground Forces Stanley Foundation

Bridging the Foreign Policy Divide The The Case for Larger Ground Forces Stanley Foundation By Frederick Kagan and Michael O’Hanlon April 2007 Frederick W. Kagan is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, specializing in defense transformation, the defense budget, and defense strategy and warfare. Previously he spent ten years as a professor of military history at the United States Military Academy (West Point). Kagan’s 2006 book, Finding the Target: The Transformation of American Military Policy (Encounter Books), exam- ines the post-Vietnam development of US armed forces, particularly in structure and fundamental approach. Kagan was coauthor of an influential January 2007 report, Choosing Victory: A Plan for Success in Iraq, advocating an increased deployment. Michael O’Hanlon is senior fellow and Sydney Stein Jr. Chair in foreign policy studies at the Brookings Institution, where he spe- cializes in U S defense strategy, the use of military force, and homeland security. O’Hanlon is coauthor most recently of Hard Power: the New Politics of National Security (Basic Books), a look at the sources of Democrats’ political vulnerability on national security in recent decades and an agenda to correct it. He previously was an analyst with the Congressional Budget Office. Brookings’ Iraq Index project, which he leads, is a regular feature on The New York Times Op-Ed page. e live at a time when wars not only rage national inspections. What will happen if the in nearly every region but threaten to US—or Israeli—government becomes convinced Werupt in many places where the current that Tehran is on the verge of fielding a nuclear relative calm is tenuous. -

The Israel Defense Forces, 1948-2017

The Israel Defense Forces, 1948-2017 Kenneth S. Brower Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 150 THE BEGIN-SADAT CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES BAR-ILAN UNIVERSITY Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 150 The Israel Defense Forces, 1948-2017 Kenneth S. Brower The Israel Defense Forces, 1948-2017 Kenneth S. Brower © The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies Bar-Ilan University Ramat Gan 5290002 Israel Tel. 972-3-5318959 Fax. 972-3-5359195 [email protected] www.besacenter.org ISSN 0793-1042 May 2018 Cover image: Soldier from the elite Rimon Battalion participates in an all-night exercise in the Jordan Valley, photo by Staff Sergeant Alexi Rosenfeld, IDF Spokesperson’s Unit The Begin-Sadat (BESA) Center for Strategic Studies The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies is an independent, non-partisan think tank conducting policy-relevant research on Middle Eastern and global strategic affairs, particularly as they relate to the national security and foreign policy of Israel and regional peace and stability. It is named in memory of Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat, whose efforts in pursuing peace laid the cornerstone for conflict resolution in the Middle East. Mideast Security and Policy Studies serve as a forum for publication or re-publication of research conducted by BESA associates. Publication of a work by BESA signifies that it is deemed worthy of public consideration but does not imply endorsement of the author’s views or conclusions. Colloquia on Strategy and Diplomacy summarize the papers delivered at conferences and seminars held by the Center for the academic, military, official and general publics. -

1St Battalion the Northamptonshire Regiment (48Th/58Th)

REGIMENTAL JOURNAL OF THE 2nd EAST ANGLIAN REGIMENT DUCHESS OF GLOUCESTER’S OWN ROYAL LINCOLNSHIRE and NORTHAMPTONSHIRE September, 1960 QUALITY I I BEERS Ask for them at your CLUB or “LOCAL” PHIPPS NORTHAMPTON BREWERY CO., LTD. J. Stevenson Holt Ltd JEFFERY’S Established in GOLD STREET since 1874 A Household Name for THE PRINTERS FOR FURNITURE - CARPETS - FABRICS BEDDING - HARDWARE - INTERIOR llegimental Sport* DECORATIONS - REMOVALS - STORAGE Services M enu « SHIPPING S t a t i o n e r y Years of Tradition, Knowledge and Service at your disposal e t c ., e t c . We extend to you a Cordial Invitation to walk • round our extensive Showrooms 20 NEWLAND, NORTHAMPTON JEFFERY, SONS & CO. LTD. Tel. Northampton I 1 4 7 33-39 GOLD STREET, NORTHAMPTON Telephone: Northampton 2349 (3 lines) 14 THE POACHER W. .b JOWNfON ir \ <^~f~OK\ 82, A NO fX-TM-AM PT O (V . TELEPHONE JUST BELOW 1414 / NEW THEATRE COMPLETE SPORTS OUTFITTERS PRESENTATIONS T e l e p h o n e : 20276 For Regimental Presentations and FRANK R ...... Wedding Gifts may we offer these suggestions from our large and varied stock ECCLESHARE SILVER CIGARETTE BOXES LIMITED CANTEENS OK CUTLERY TABLE LIGHTERS Building Contractors ELLIOTT CLOCKS CUT GLASS DIXON STREET SILVER SALVERS IVORY MILITARY BRUSHES LINCOLN BINOCULARS OMEGA WATCHES All classcs o f Painting and Decorating W. MANSELL Property Repairs and Alterations SILVER STREET LINCOLN FREE ESTIMATES ii THE POACHER — — LINCOLN NORTHAMPTON = THE TWO COUNTIES .... WILL BE WELL SERVED BY THE NEW REGIMENT THE TWO COUNTIES .... ARE ALREADY WELL SERVED BY LINCOLNSHIRE ROAD . UNITED COUNTIES CAR COMPANY LTD and OMNIBUS COMPANY LTD WHOLE NETWORK OF DAILY SERVICES THROUGHOUT BOTH COUNTIES Super Coaches for Private Hire and Excursions ST. -

The Evolution of U.S. Military Policy from the Constitution to the Present

C O R P O R A T I O N The Evolution of U.S. Military Policy from the Constitution to the Present Gian Gentile, Michael E. Linick, Michael Shurkin For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1759 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9786-6 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Since the earliest days of the Republic, American political and military leaders have debated and refined the national approach to providing an Army to win the nation’s independence and provide for its defense against all enemies, foreign and domestic. -

Report of Investigation Concerning RC-26B Operations 1-4 June 2020

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. Introduction .......................................................................................................................1 II. Background .......................................................................................................................4 III. Standards and Authorities .................................................................................................7 IV. Discussion and Analysis .................................................................................................18 V. Summary .........................................................................................................................68 VI. Recommendations ...........................................................................................................69 This is a protected document. It will not b released (in whole or in part), reproduced, or given additional dissemination (in whole or in part) outside of he inspector ge eral channels without prior approval of The Inspector Ge eral (SAF/IG) o designee. FOR OFFIC\ AL USE \ON Y (FOUO) In addition, the President can activate the National Guard to participate in federal missions, both domestically and overseas. When federalized, Guard units fall under the same military chain of command as active duty and reserve personnel. (Ex 14) The senior military commander for each state and territory is The Adjutant General (TAG) and in most cases reports directly to their Governors (32 U.S. Code § 314.Adjutants general). Under the District of Columbia -

13.1. for COMPONENT ASSIGNMENTS. CMD Will Use The

13.1. FOR COMPONENT ASSIGNMENTS. CMD will use the digraphs and trigraphs in Table 26 for the DoD and OSD Component heads, as appropriate, when assigning actions in CATMS, in suspense reports, and on the SD Form 391. Questions regarding them may be directed to CMD at whs.pentagon.esd.mbx.cmd- [email protected]. Table 26. Digraphs and Trigraphs for Action or Information Component Assigned OSD Entities SD Secretary of Defense (Assign Action to ES) DSD Deputy Secretary of Defense COS The Special Assistant to the Secretary and Deputy Secretary of Defense MAS Military Assistan t to the Secretary of Defense MAD Military Assistan t to the Deputy Secretary of Defense COS Chief of Staff ES Executive Secretary of the Department of Defense ESR Executive Secretariat Rear ESW Executive Secretary White House Actions PRO Protocol SDS Secretary of Defense Scheduling DS Deputy Secretary of Defense Scheduling TNT Transition T eam USA Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment URE Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering USP Under Secretary of Defense for Policy USC Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller)/Chief Financial Officer UPR Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness USI Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security CMO Chief Management Officer CIO DoD Chief Information Officer LA Assistant Secretary of Defense for Legislative Affairs PA Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs GC General Counsel of the Department of Defense OTE Director of Operational Test and Evaluation CAP Director, Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation IG Inspector General of the Department of Defense NA Director of Net Assessment Military Departments SA Secretary of the Army SAF Secretary of the Air Force SN Secretary of the Navy SECTION 13: OFFICIAL DIGRAPHS AND TRIGRAPHS 86 DoDM 5110.04, Volume 1, June 16, 2020 Table 26. -

Polish Battles and Campaigns in 13Th–19Th Centuries

POLISH BATTLES AND CAMPAIGNS IN 13TH–19TH CENTURIES WOJSKOWE CENTRUM EDUKACJI OBYWATELSKIEJ IM. PŁK. DYPL. MARIANA PORWITA 2016 POLISH BATTLES AND CAMPAIGNS IN 13TH–19TH CENTURIES WOJSKOWE CENTRUM EDUKACJI OBYWATELSKIEJ IM. PŁK. DYPL. MARIANA PORWITA 2016 Scientific editors: Ph. D. Grzegorz Jasiński, Prof. Wojciech Włodarkiewicz Reviewers: Ph. D. hab. Marek Dutkiewicz, Ph. D. hab. Halina Łach Scientific Council: Prof. Piotr Matusak – chairman Prof. Tadeusz Panecki – vice-chairman Prof. Adam Dobroński Ph. D. Janusz Gmitruk Prof. Danuta Kisielewicz Prof. Antoni Komorowski Col. Prof. Dariusz S. Kozerawski Prof. Mirosław Nagielski Prof. Zbigniew Pilarczyk Ph. D. hab. Dariusz Radziwiłłowicz Prof. Waldemar Rezmer Ph. D. hab. Aleksandra Skrabacz Prof. Wojciech Włodarkiewicz Prof. Lech Wyszczelski Sketch maps: Jan Rutkowski Design and layout: Janusz Świnarski Front cover: Battle against Theutonic Knights, XVI century drawing from Marcin Bielski’s Kronika Polski Translation: Summalinguæ © Copyright by Wojskowe Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej im. płk. dypl. Mariana Porwita, 2016 © Copyright by Stowarzyszenie Historyków Wojskowości, 2016 ISBN 978-83-65409-12-6 Publisher: Wojskowe Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej im. płk. dypl. Mariana Porwita Stowarzyszenie Historyków Wojskowości Contents 7 Introduction Karol Olejnik 9 The Mongol Invasion of Poland in 1241 and the battle of Legnica Karol Olejnik 17 ‘The Great War’ of 1409–1410 and the Battle of Grunwald Zbigniew Grabowski 29 The Battle of Ukmergė, the 1st of September 1435 Marek Plewczyński 41 The -

Fiscal Year 2020 Legislative Resolutions 2 Legislative Resolutions

FISCAL YEAR 2020 LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTIONS 2 LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTIONS // www.ngaus.org CONTENTS www.ngaus.org // LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTIONS 3 4. A Letter from Our Chairman 24. Air Resolutions 6. About NGAUS 56. Joint Resolutions 8. NGAUS Legislative Team 92. NGAUS Board of Directors 10. The Guard in the Federal Budget 94. NGAUS Areas 12. Resolutions Timeline 96. Area Directors 14. Army Resolutions 98. NGAUS Staff 4 LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTIONS // www.ngaus.org A LETTER FROM OUR CHAIRMAN www.ngaus.org // LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTIONS 5 It is my privilege to present the Fiscal Year 2020 Legislative Resolutions of the National Guard Association of the United States (NGAUS) on behalf of our nearly 45,000 members. Our mission to advocate for the National Guard in Congress has not changed since our formation in 1878. However, the National Guard and NGAUS’ priorities change as the global threat environment changes. The National Guard is essential to the defense of our nation now, more than ever, as homeland defense and great power competition return to the forefront of the National Defense Strategy. Secretary of Defense James N. Mattis said during this year’s NGAUS General Conference and Exhibition in New Orleans, “Everything we do must contribute to increased lethality. So we need you, my fine young National Guardsmen, at the top of your game. Lethality begins when we are physically, mentally, and spiritually fit to be evaluated by the most exacting auditor on earth. And that auditor is war.” Enhanced lethality means maximum readiness. National Guard readiness includes current and proportional fielding of new equipment and weapons platforms to units that are in line with Army and Air Force requirements, legacy platform modernization and recapitalization to ensure safety and reliability, as well Major General as accessibility to robust health care to ensure continuity of care, and deployability for National Guard Donald Dunbar personnel. -

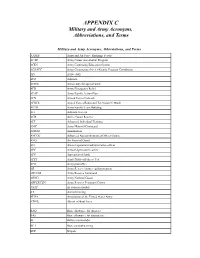

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College