Yakuwarigo in Japanese Language, Literature and Translation – New Approaches to the Concept of Role Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013/02 FACTBOOK 2012 (English)

FACTBOOK 2012 Global COE Office, School of Law, Tohoku University 27-1 Kawauchi, Aoba, Sendai, Miyagi 980-8576 Japan TEL +81-(0)22-795-3740, +81-(0)22-795-3163 FAX +81-(0)22-795-5926 E-mail [email protected] URL http://www.law.tohoku.ac.jp/gcoe/en/ Gender Equality and Multicultural Conviviality in the Age of Globalization F A C T B O O K 2 0 1 2 Tohoku University Global COE Program Gender Equality and Multicultural Conviviality in the Age of Globalization Please visit our website http://www.law.tohoku.ac.jp/gcoe/en/ FACTBOOK英表紙-六[1-2].indd 1 2013/01/31 15:38:46 Gender Equality and Multicultural Conviviality in the Age of Globalization CONTENTS 1 Foreword 2 Mission Statement 3 Ⅰ Program Outline 4 ACCESS Program Outline 5 Program Members / Global COE Organizational Chart 7 Ⅱ Research Projects 8 15 Research Projects 9 Global COE Office, Tohoku University (Sendai City) Ⅲ Human Resources Development 26 School of Law, Sendai City Hall Miyagi Prefectural government Atagokamisugidori Avenue Tohoku University Sendainiko Mae Cross-National Doctoral Course(CNDC) 27 Bansuidori Avenue Kotodai Station CNDC Student Profiles 29 Jozenjidori Avenue Shopping Mall Achievements 32 27-1 Kawauchi, Aoba-ku, Sendai 980-8576 Miyagi Museum of Art Sendai-Daini High School GCOE Fellows and Research Assistants 33 TEL: +81-22-795-3740, +81-22-795-3163 FAX: +81-22-795-5926 Kawauchi Campus E-mail: [email protected] Hirosedori Avenue Hirosedori Station Main Activities in Academic Year 2012 Bus Stop Ⅳ http://www.law.tohoku.ac.jp/gcoe/en/ (Kawauchi Campus) -

Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin This page intentionally left blank Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin University of Tokyo, Japan Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin Introduction, selection -

Japan and the Moneylenders—Activist Courts and Substantive Justice

Washington International Law Journal Volume 17 Number 3 6-1-2008 Japan and the Moneylenders—Activist Courts and Substantive Justice Andrew M. Pardieck Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons, and the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Andrew M. Pardieck, Japan and the Moneylenders—Activist Courts and Substantive Justice, 17 Pac. Rim L & Pol'y J. 529 (2008). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj/vol17/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington International Law Journal by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright © 2008 Pacific Rim Law & Policy Journal Association JAPAN AND THE MONEYLENDERS— ACTIVIST COURTS AND SUBSTANTIVE JUSTICE Andrew M. Pardieck† Abstract: Problems with sub-prime loans roiled financial markets worldwide in 2007 and brought renewed attention to predatory lending practices by loan brokers in the United States. Questionable lending practices, however, plague consumer financial markets worldwide, including one of the largest, found in Japan. This Article addresses the Japanese response to systemic problems in its consumer finance market. Over the last forty years, the judiciary has led and the Diet followed. Most recently, in 2006, the Supreme Court handed down a series of decisions that turned the single most important earnings driver for the consumer finance industry into dead letter law. The Diet followed with legislative revisions. -

URL &6Allein 【BD】&A

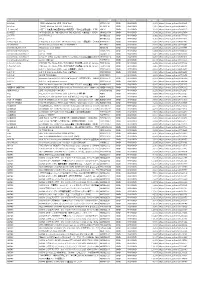

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL &6allein 【BD】&6allein 1st LIVE「With You」 MEXV0014 DVD J-POP DVD 3,850 https://tower.jp/item/4844321 &6allein 【DVD】&6allein 1st LIVE「With You」 MESV0135 DVD J-POP DVD 2,800 https://tower.jp/item/4844315 【_Vani;lla】 平成二十年度提出漏春夏秋冬狂声聴視覚集 <初回生産限定盤>(LTD) VNLV1 DVD J-POP DVD 1,966 https://tower.jp/item/2641212 10-FEET OF THE KIDS,BY THE KIDS,FOR THE KIDS!VII <通常盤>(BRD) UPXH20074 DVD J-POP DVD 3,360 https://tower.jp/item/4815474 24-7 TV 24-7 TV Vol.1 BMPB1001 DVD J-POP DVD 1,400 https://tower.jp/item/1677660 24-7 TV Vol.2 BMPB1002 DVD J-POP DVD 1,400 https://tower.jp/item/1684914 3 Majesty/X.I.P. 3 Majesty × X.I.P. LIVE -5th Anniversary Tour- <豪華版> [3DVD KEBH9068 DVD J-POP DVD 8,960 https://tower.jp/item/4862667 420 FAMILY STORYa Documentary Film of 420FAMILY FTOV420 DVD J-POP DVD 2,800 https://tower.jp/item/3267351 9GOATS BLACK OUT Melancholy pool(DIGI) NINE005 DVD J-POP DVD 2,867 https://tower.jp/item/2884774 9mm Parabellum Bullet act VII COBA7080 DVD J-POP DVD 6,999 https://tower.jp/item/4891530 9mm Parabellum Bullet act VII(BRD) COXA1177 DVD J-POP DVD 8,400 https://tower.jp/item/4891528 9mm Parabellum Bullet act O+E [2Blu-ray Disc+DVD+シリアルNo.入りAAA武道館スタッフパUPXH29009 DVD J-POP DVD 8,400 https://tower.jp/item/3452601 9mm Parabellum Bullet act IV <通常盤> TOBF5740 DVD J-POP DVD 2,143 https://tower.jp/item/3066116 a flood of circle I'M FREE The Movie-形ないものを爆破する映像集- 2014.04.12 Live aTEBI48303 DVD J-POP DVD 2,250 https://tower.jp/item/3547902 a flood of circle I'M FREE The Movie-形ないものを爆破する映像集- 2014.04.12 Live aTEBI53302 -

Social Investment Policy and Education in Japan

April 2020 No. 5 Published by the Japan Association for Social Policy Studies (JASPS) All Inquiries to info-english@jasps.org Social investment policy and education in Japan IGAMI, Ko Kobe International University 1. Introduction: The status of social investment definition, social investment policy is policy research in Japan commonly understood as the entirety of I would like to begin with an overview policies that recognize welfare not as mere of the status of social investment policy “spending” but as an “investment” to deliver research in Japan, which is based on the “returns” (profits). Its aim is to make policy interests relevant to the restoration of welfare and economic growth compatible the welfare state that became popular in the with each other by enhancing social services 1990s, particularly in Europe. That is, these to support people’s participation in the labor policy interests related to ways in which the market, mainly through the investment welfare state could respond to “new social in “human capital” to raise individuals’ risks,” including unstable careers and child- potential. care/elderly-care responsibilities associated Many social policy scholars in Japan are with the expansion of non-regular employment welfare state researchers with a keen and the growth of two-income families. This interest in researching social investment new model superseded the “traditional social policy. It is undeniable, however, that social risks,” such as unemployment, aging, illness, investment policy research in Japan has and so forth, which was based on the family mostly been focused on debate within model of the regularly employed male European countries, such as the United breadwinner, which had been assumed in Kingdom, the Netherlands, France, and the 20th-century welfare state. -

Read the Full PDF

Job Name:2133916 Date:15-01-28 PDF Page:2133916pbc.p1.pdf Color: Cyan Magenta Yellow Black The American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, established in 1943, is a publicly supported, nonpartisan, research and educational organization. Its purpose is to assist policy makers, scholars, businessmen, the press, and the public by providing objective analysis of national and international issues. Views expressed in the institute's publications are those of the authors and do not neces sarily reflect the views of the staff, advisory panels, officers, or trustees of AEI. Council of Academic Advisers Paul W. McCracken, Chairman, Edmund Ezra Day University Professor of Busi ness Administration, University of Michigan Robert H. Bork, Alexander M. Bickel Professor of Public Law, Yale Law School Kenneth W. Dam, Harold I. and Marion F. Green Professor of Law, University of Chicago Law School Donald C. Hellmann, Professor of Political Science and International Studies, University of Washington D. Gale Johnson, Eliakim Hastings Moore Distinguished Service Professor of Economics and Provost, Llniversity of Chicago Robert A. Nisbet, Resident Scholar, American Enterprise Institute Herbert Stein, A. Willis Robertson Professor of Economics, University of Virginia Marina v. N. Whitman, Distinguished Public Service Professor of Economics, Uni- versity of Pittsburgh James Q. Wilson, Henry Lee Shattuck Professor of Government, Harvard University Executive Committee Herman J. Schmidt, Chairman of the Board Richard J. Farrell William J. Baroody, Jr., President Richard B. Madden Charles T. Fisher III, Treasurer Richard D. Wood Gary L. Jones, Vice President, Edward Styles, Director of Administration Publications Program Directors Periodicals Russell Chapin, Legislative Analyses AEI Economist, Herbert Stein, Editor Robert B. -

O Japonês Como Língua Estrangeira

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LINGÜÍSTICA Leiko Matsubara Morales Cem anos de imigração japonesa no Brasil: o japonês como língua estrangeira Tese apresentada ao Curso de Pós-Graduação em Lingüística, Área de Concentração em Semiótica e Lingüística Geral, do Departamento de Lingüística da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo, para obtenção de grau de Doutor em Lingüística Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Maria Cristina Fernandes Salles Altman São Paulo 2008 BANCA EXAMINADORA _____________________________________________________ Profa. Dra. Maria Cristina Fernandes Salles Altman (orientadora) _____________________________________________________ Profa. Dra. Elza Taeko Doi _____________________________________________________ Profa. Dra. Olga Ferreira Coelho _____________________________________________________ Profa. Dra. Junko Ota ______________________________________________________ Profa. Dra. Ana Flávia Lopes Magela Gerhardt Agradecimentos À professora Maria Cristina Salles Fernandes Altman, pela confiança de ter permitido que eu trabalhasse autonomamente e pelo respeito às minhas limitações. À professora Elza Taeko Doi, pela orientação na organização e na análise dos dados e pela inspiração e exemplo de pesquisador. Às professoras Michiko Sasaki e Satoko Nochida, pelo envio de livros e dados importantes sobre o ensino de língua japonesa na perspectiva de língua de herança. À professora Mitsuyo Sakamoto, pelo envio de artigos preciosos de bibliotecas japonesas. À professora Edna Mayumi Iko Yoshikawa, pela colaboração nos dados e na inspiração pela pesquisa. Ao professor Yuki Mukai, pela ajuda na coleta de dados e constante incentivo na pesquisa. Aos professores Keishi Izuno, Tomiko Takahashi, Reishi Moriwaki, Masayo Ueno, Sumiko Fuchida, Akiko Miyake, Tizu Muranaka, Mitsuko Nakasumi, Masaru Yanagimori e Masaho Tazuke pelos empréstimos de livros, fotos e dados preciosos. -

POSTWAR CONSTITUTION Secondary Sources – Journal Articles and Book Chapters

1 POSTWAR CONSTITUTION Secondary Sources – Journal articles and book chapters The American Journal of International Law 1949 Arikawa v. Acheson. vol.43, no. 4, 810. Asu eno sentaku 明日への選択 2013 Kenpō "kaisei hantairon" daironpa 憲法「改正反対論」大論破 Asu eno sentaku 明日への選択 vol. 333, 10-20. 2013 "Sensō eno hansei" kara heiwa kenpō wa umareta? (Zoku kenpō "kaisei hantairon" daironpa) 「戦争への反省」から平和憲法は生まれた?(続 憲法 「改正反対論」大論破). Asu eno sentaku 明日への選択 vol. 334, 12-14. 2013 Jinken wa "kōeki" ni yotte seiyaku shite wa naranai? (Zoku kenpō "kaisei hantairon" daironpa 人権は「公益」によって制約してはならない?(続 憲法 「改正反対論」大論破). Asu eno sentaku 明日への選択 vol. 334, 14-17. 2013 Kihon-teki jinken wa kokka yori yūsen suru? (Zoku kenpō "kaisei hantairon" daironpa) 基本的人権は国家よりも優先する?(続 憲法「改正反対論」大論 破). Asu eno sentaku 明日への選択 vol. 334, 17-20. 2014 Mou hitotsu no seikenshi (saishūkai) "kenpō kaisei seifu shian" o kanzen hitei shita sōshireibu shikasi soko ni mo Nōman ra no kōsaku ga irokoku han'ei sarete ita もう⼀つの制憲史(最終回)「憲法改正政府試案」を完全否定した 総司令部。しかし、そこにもノーマンらの工作が色濃く反映されていた. Asu e no sentaku 明日への選択 vol. 336, 26-30. 2014 "Kinkyū jitai" taisho no kenpō kaisei wa matta nashi 「緊急事態」対処の憲法 改正は待ったなし. Asu e no sentaku 明日への選択 vol. 345, 10-14. 2014 Kenpō kaisei rongi ni nani ga yūsen sareru beki ka 憲法改正論議に何が優先さ れるべきか. Asu e no sentaku 明日への選択 vol. 340, 30-34. Chian Mondai Kenkyūkai 治安問題研究会 2006 Nihon Kyōsantō to kenpō: Nihon Kyōsantō wa "goken" no tō ka? (tokushū kenpō kaisei mondai) 日本共産党と憲法: 日本共産党は「護憲」の党か? ( 特集: 憲法改正問題). Gekkan Chian Fōramu 月刊治安フォーラム vol.12, no. 6, 18-28. 2013 Nihon kyōsantō to kenpō kaisei (Tokushū kenpō kaisei mondai to chian) 日本 共産党と憲法改正(特集 憲法改正問題と治安). -

An Ethnographic Study of the Politics of Identity and Belonging Jane Esther

Being LGBT in Japan: An ethnographic study of the politics of identity and belonging Jane Esther Wallace Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Languages, Cultures, and Societies and School of Sociology and Social Policy July 2018 ii iii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Jane Esther Wallace to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © The University of Leeds and Jane Esther Wallace iv Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to thank all of the respondents and gatekeepers who made this research possible. Without your time and patience, this research could not have happened. I would also like to thank those who have continued to guide me and provide feedback on my analysis during the analysis stage. This research was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council of Great Britain, with reference 1368644. I also received funding from the British Association of Japanese Studies through the John Crump Scholarship, with reference JC2017_35. I would also like to thank the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation (GBSF), who supported me financially with a 6-month scholarship and invited me to various GBSF workshops and events. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Quality of This Reproduction Is

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. ÜMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy suhmitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 NOTE TO USERS The original manuscript received by UMI contains indistinct, slanted and or light print. All efforts were made to acquire the highest quality manuscript from the author or school. -

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) Homology theory Ka nanʻʺ (Burmese people) (May Subd Geog) USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) NT Whitehead groups [DS528.2.K2] K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) K. Tzetnik Award in Holocaust Literature UF Ka tūʺ (Burmese people) USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) UF Ka-Tzetnik Award BT Ethnology—Burma K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) Peras Ḳ. Tseṭniḳ ʾKa nao dialect (May Subd Geog) UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) Peras Ḳatseṭniḳ BT China—Languages K9 (Fictitious character) BT Literary prizes—Israel Hmong language K 37 (Military aircraft) K2 (Pakistan : Mountain) Ka nō (Burmese people) USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) UF Dapsang (Pakistan) USE Tha noʹ (Burmese people) K 98 k (Rifle) Godwin Austen, Mount (Pakistan) Ka Rang (Southeast Asian people) USE Mauser K98k rifle Gogir Feng (Pakistan) USE Sedang (Southeast Asian people) K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 Mount Godwin Austen (Pakistan) Ka-taw USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 BT Mountains—Pakistan USE Takraw K.A. Lind Honorary Award Karakoram Range Ka Tawng Luang (Southeast Asian people) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris K2 (Drug) USE Phi Tong Luang (Southeast Asian people) K.A. Linds hederspris USE Synthetic marijuana Kā Tiritiri o te Moana (N.Z.) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris K3 (Pakistan and China : Mountain) USE Southern Alps/Kā Tiritiri o te Moana (N.Z.) K-ABC (Intelligence test) USE Broad Peak (Pakistan and China) Ka-Tu USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children K4 (Pakistan and China : Mountain) USE Kha Tahoi K-B Bridge (Palau) USE Gasherbrum II (Pakistan and China) Ka tūʺ (Burmese people) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) K4 Locomotive #1361 (Steam locomotive) USE Ka nanʻʺ (Burmese people) K-BIT (Intelligence test) USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) Ka-Tzetnik Award USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test K5 (Pakistan and China : Mountain) USE K. -

Colloquial Japanese: the Complete Course for Beginners, Second Edition

Colloquial Japanese The Colloquial Series Series Adviser: Gary King The following languages are available in the Colloquial series: Afrikaans * Japanese Albanian Korean Amharic Latvian Arabic (Levantine) Lithuanian Arabic of Egypt Malay Arabic of the Gulf and Mongolian Saudi Arabia Norwegian Basque Panjabi Bulgarian Persian * Cambodian Polish * Cantonese Portuguese * Chinese Portuguese of Brazil Croatian and Serbian Romanian Czech Russian Danish Scottish Gaelic Dutch Slovak Estonian Slovene Finnish Somali French * Spanish German Spanish of Latin America Greek Swedish Gujarati * Thai Hindi Turkish Hungarian Ukrainian Icelandic Urdu Indonesian * Vietnamese Italian Welsh Accompanying cassette(s) (*and CDs) are available for the above titles. They can be ordered through your bookseller, or send payment with order to Taylor & Francis/Routledge Ltd, ITPS, Cheriton House, North Way, Andover, Hants SP10 5BE, UK, or to Routledge Inc, 29 West 35th Street, New York NY 10001, USA. COLLOQUIAL CD-ROMs Multimedia Language Courses Available in: Chinese, French, Portuguese and Spanish Colloquial Japanese The Complete Course for Beginners Second edition Hugh Clarke and Motoko Hamamura First published 2003 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group © 2003 Hugh Clarke and Motoko Hamamura Typeset in Times New Roman by Newgen Imaging Systems (P) Ltd, Chennai, India Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall All rights reserved.