Colloquial Japanese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morphological Clues to the Relationships of Japanese and Korean

Morphological clues to the relationships of Japanese and Korean Samuel E. Martin 0. The striking similarities in structure of the Turkic, Mongolian, and Tungusic languages have led scholars to embrace the perennially premature hypothesis of a genetic relationship as the "Altaic" family, and some have extended the hypothesis to include Korean (K) and Japanese (J). Many of the structural similarities that have been noticed, however, are widespread in languages of the world and characterize any well-behaved language of the agglutinative type in which object precedes verb and all modifiers precede what is mod- ified. Proof of the relationships, if any, among these languages is sought by comparing words which may exemplify putative phono- logical correspondences that point back to earlier systems through a series of well-motivated changes through time. The recent work of John Whitman on Korean and Japanese is an excellent example of productive research in this area. The derivative morphology, the means by which the stems of many verbs and nouns were created, appears to be largely a matter of developments in the individual languages, though certain formants have been proposed as putative cognates for two or more of these languages. Because of the relative shortness of the elements involved and the difficulty of pinning down their semantic functions (if any), we do well to approach the study of comparative morphology with caution, reconstructing in depth the earliest forms of the vocabulary of each language before indulging in freewheeling comparisons outside that domain. To a lesser extent, that is true also of the grammatical morphology, the affixes or particles that mark words as participants in the phrases, sentences (either overt clauses or obviously underlying proposi- tions), discourse blocks, and situational frames of reference that constitute the creative units of language use. -

The Japan News / Recipe

Recipe Depth and variety of Japan’s cuisine The “Delicious” page, published every Tuesday, introduces simple recipes, restaurants across the country and extensive background information about Japanese washoku cuisine. By uncovering the history of Japanese food and sharing choice anecdotes, we make cooking at home and dining out even more fun. Our recipe columns In this column, we look back over changes in Japanese cuisine by featuring popular recipes carried in The Yomiuri Shimbun over the past century. Preparing a meal for oneself often comes with many complaints such as, “Cooking just for me is annoying,” and “I don’t know if I can eat everything by myself.” In this series, cooking researchers share tips for making delicious meals just for you. In this column, Tamako Sakamoto, a culinary expert who previously wrote the column “Taste of Home” for The Japan News, introduces tips for home-style dishes typically enjoyed by Japanese families. Taste of Japanese mom Chikuzen-ni Chikuzen refers to northwestern Fukuoka Prefecture. Although the dish is widely known as Chikuzen-ni, local people usually call the dish game-ni. There are several possible origins of the name. One idea is that it comes from “gamekomu,” a local dialect word for “bringing together” various leftover vegetables, even scraps, in a pan. Another theory is that turtle (kame) or soft-shelled turtle (suppon) were cooked together. There are also various views about the roots of the dish. One is that it was a battlefield dish of the Kuroda clan in the Chikuzen district, while another suggests the dish was created by warriors who were stationed in Hakata, Fukuoka Prefecture, when Toyotomi Hideyoshi sent a large army to the Korean Peninsula in the 16th century. -

Hayashi Fumiko: the Writer and Her Works

University at Albany, State University of New York Scholars Archive East Asian Studies Faculty Scholarship East Asian Studies 1994 Hayashi Fumiko: The Writer and Her Works Susanna Fessler PhD University at Albany, State University of New York, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/eas_fac_scholar Part of the Japanese Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fessler, Susanna PhD, "Hayashi Fumiko: The Writer and Her Works" (1994). East Asian Studies Faculty Scholarship. 13. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/eas_fac_scholar/13 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the East Asian Studies at Scholars Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Asian Studies Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. Hie quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the qualify of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bieedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

The Languages of Japan and Korea. London: Routledge 2 The

To appear in: Tranter, David N (ed.) The Languages of Japan and Korea. London: Routledge 2 The relationship between Japanese and Korean John Whitman 1. Introduction This chapter reviews the current state of Japanese-Ryukyuan and Korean internal reconstruction and applies the results of this research to the historical comparison of both families. Reconstruction within the families shows proto-Japanese-Ryukyuan (pJR) and proto-Korean (pK) to have had very similar phonological inventories, with no laryngeal contrast among consonants and a system of six or seven vowels. The main challenges for the comparativist are working through the consequences of major changes in root structure in both languages, revealed or hinted at by internal reconstruction. These include loss of coda consonants in Japanese, and processes of syncope and medial consonant lenition in Korean. The chapter then reviews a small number (50) of pJR/pK lexical comparisons in a number of lexical domains, including pronouns, numerals, and body parts. These expand on the lexical comparisons proposed by Martin (1966) and Whitman (1985), in some cases responding to the criticisms of Vovin (2010). It identifies a small set of cognates between pJR and pK, including approximately 13 items on the standard Swadesh 100 word list: „I‟, „we‟, „that‟, „one‟, „two‟, „big‟, „long‟, „bird‟, „tall/high‟, „belly‟, „moon‟, „fire‟, „white‟ (previous research identifies several more cognates on this list). The paper then concludes by introducing a set of cognate inflectional morphemes, including the root suffixes *-i „infinitive/converb‟, *-a „infinitive/irrealis‟, *-or „adnominal/nonpast‟, and *-ko „gerund.‟ In terms of numbers of speakers, Japanese-Ryukyuan and Korean are the largest language isolates in the world. -

Probability and Counting Rules

blu03683_ch04.qxd 09/12/2005 12:45 PM Page 171 C HAPTER 44 Probability and Counting Rules Objectives Outline After completing this chapter, you should be able to 4–1 Introduction 1 Determine sample spaces and find the probability of an event, using classical 4–2 Sample Spaces and Probability probability or empirical probability. 4–3 The Addition Rules for Probability 2 Find the probability of compound events, using the addition rules. 4–4 The Multiplication Rules and Conditional 3 Find the probability of compound events, Probability using the multiplication rules. 4–5 Counting Rules 4 Find the conditional probability of an event. 5 Find the total number of outcomes in a 4–6 Probability and Counting Rules sequence of events, using the fundamental counting rule. 4–7 Summary 6 Find the number of ways that r objects can be selected from n objects, using the permutation rule. 7 Find the number of ways that r objects can be selected from n objects without regard to order, using the combination rule. 8 Find the probability of an event, using the counting rules. 4–1 blu03683_ch04.qxd 09/12/2005 12:45 PM Page 172 172 Chapter 4 Probability and Counting Rules Statistics Would You Bet Your Life? Today Humans not only bet money when they gamble, but also bet their lives by engaging in unhealthy activities such as smoking, drinking, using drugs, and exceeding the speed limit when driving. Many people don’t care about the risks involved in these activities since they do not understand the concepts of probability. -

Music Law 102

Music Law 102 2019 Edition LawPracticeCLE Unlimited All Courses. All Formats. All Year. ABOUT US LawPracticeCLE is a national continuing legal education company designed to provide education on current, trending issues in the legal world to judges, attorneys, paralegals, and other interested business professionals. New to the playing eld, LawPracticeCLE is a major contender with its oerings of Live Webinars, On-Demand Videos, and In-per- son Seminars. LawPracticeCLE believes in quality education, exceptional customer service, long-lasting relationships, and networking beyond the classroom. We cater to the needs of three divisions within the legal realm: pre-law and law students, paralegals and other support sta, and attorneys. WHY WORK WITH US? At LawPracticeCLE, we partner with experienced attorneys and legal professionals from all over the country to bring hot topics and current content that are relevant in legal practice. We are always looking to welcome dynamic and accomplished lawyers to share their knowledge! As a LawPracticeCLE speaker, you receive a variety of benets. In addition to CLE teaching credit attorneys earn for presenting, our presenters also receive complimentary tuition on LawPracticeCLE’s entire library of webinars and self-study courses. LawPracticeCLE also aords expert professors unparalleled exposure on a national stage in addition to being featured in our Speakers catalog with your name, headshot, biography, and link back to your personal website. Many of our courses accrue thousands of views, giving our speakers the chance to network with attorneys across the country. We also oer a host of ways for our team of speakers to promote their programs, including highlight clips, emails, and much more! If you are interested in teaching for LawPracticeCLE, we want to hear from you! Please email our Directior of Operations at [email protected] with your information. -

Empowerment Based Co-Creative Action Research

Empowerment Based Co-Creative Action Research Action Research Based Co-Creative Empowerment Towards A World of Possibilities for Sustainable Society for Sustainable of Possibilities World A Towards Empowerment Based Co-Creative Action Research Towards A World of Possibilities for Sustainable Society Tokie Anme, PhD Editor Tokie Anme, PhD Editor Tokie Introduction is book was designed for those who feel that they can do something to improve society. Is it enough to be swept away during major changes in society, such as climate change, resource depletion, poverty and social unrest, and the spread of infectious diseases? If I want to do something to make a dierence for the better world, what is an eective method? Action research based on empowerment is a tool to steadily support a step-by-step approach on the path to change society. In this book, we focus on co-creative action research that we create together, among the many kinds of action research methods. is is because the realization of a sustainable society, through SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals), is based on empowerment that draws out the power of the involved and produces the greatest energy for change. Empowerment is to give people dreams and hopes, encourage them, and bring out the wonderful power of life that they originally have. Everyone is born with great power. And you can continue to exert great power throughout your life. Empowerment is to bring out that wonderful power. Just as gushing out from the spring, it is critical to bring out the vitality and potential of each person. In practices such as health, medical care, welfare, education, psychology, administration, management, and community development, the wonderful potential that each person originally has is brought up and manifested, and through activities, can create positive change for the development of people's lives and society. -

2013/02 FACTBOOK 2012 (English)

FACTBOOK 2012 Global COE Office, School of Law, Tohoku University 27-1 Kawauchi, Aoba, Sendai, Miyagi 980-8576 Japan TEL +81-(0)22-795-3740, +81-(0)22-795-3163 FAX +81-(0)22-795-5926 E-mail [email protected] URL http://www.law.tohoku.ac.jp/gcoe/en/ Gender Equality and Multicultural Conviviality in the Age of Globalization F A C T B O O K 2 0 1 2 Tohoku University Global COE Program Gender Equality and Multicultural Conviviality in the Age of Globalization Please visit our website http://www.law.tohoku.ac.jp/gcoe/en/ FACTBOOK英表紙-六[1-2].indd 1 2013/01/31 15:38:46 Gender Equality and Multicultural Conviviality in the Age of Globalization CONTENTS 1 Foreword 2 Mission Statement 3 Ⅰ Program Outline 4 ACCESS Program Outline 5 Program Members / Global COE Organizational Chart 7 Ⅱ Research Projects 8 15 Research Projects 9 Global COE Office, Tohoku University (Sendai City) Ⅲ Human Resources Development 26 School of Law, Sendai City Hall Miyagi Prefectural government Atagokamisugidori Avenue Tohoku University Sendainiko Mae Cross-National Doctoral Course(CNDC) 27 Bansuidori Avenue Kotodai Station CNDC Student Profiles 29 Jozenjidori Avenue Shopping Mall Achievements 32 27-1 Kawauchi, Aoba-ku, Sendai 980-8576 Miyagi Museum of Art Sendai-Daini High School GCOE Fellows and Research Assistants 33 TEL: +81-22-795-3740, +81-22-795-3163 FAX: +81-22-795-5926 Kawauchi Campus E-mail: [email protected] Hirosedori Avenue Hirosedori Station Main Activities in Academic Year 2012 Bus Stop Ⅳ http://www.law.tohoku.ac.jp/gcoe/en/ (Kawauchi Campus) -

Silva Iaponicarum 日林 Fasc. Xxxii/Xxxiii 第三十二・三十三号

SILVA IAPONICARUM 日林 FASC. XXXII/XXXIII 第第第三第三三三十十十十二二二二・・・・三十三十三三三号三号号号 SUMMER/AUTUMN 夏夏夏・夏・・・秋秋秋秋 2012 SPECIAL EDITION MURZASICHLE 2010 edited by Aleksandra Szczechla Posnaniae, Cracoviae, Varsoviae, Kuki MMXII ISSN 1734-4328 2 Drodzy Czytelnicy. Niniejszy specjalny numer Silva Iaponicarum 日林 jest juŜ drugim z serii tomów powarsztatowych i prezentuje dorobek Międzynarodowych Studenckich Warsztatów Japonistycznych, które odbyły się w Murzasichlu w dniach 4-7 maja 2010 roku. Organizacją tego wydarzenia zajęli się, z pomocą kadry naukowej, studenci z Koła Naukowego Kappa, działającego przy Zakładzie Japonistyki i Sinologii Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. Warsztaty z roku na rok (w momencie edycji niniejszego tomu odbyły się juŜ czterokrotnie) zyskują coraz szersze poparcie zarówno władz uczestniczących Uniwersytetów, Rady Kół Naukowych, lecz przede wszystkim Fundacji Japońskiej oraz Sakura Network. W imieniu organizatorów redakcja specjalnego wydania Silvy Iaponicarum pragnie jeszcze raz podziękować wszystkim Sponsorom, bez których udziału organizacja wydarzenia tak waŜnego w polskim kalendarzu japonistycznym nie miałaby szans powodzenia. Tom niniejszy zawiera teksty z dziedziny językoznawstwa – artykuły Kathariny Schruff, Bartosza Wojciechowskiego oraz Patrycji Duc; literaturoznawstwa – artykuły Diany Donath i Sabiny Imburskiej- Kuźniar; szeroko pojętych badań kulturowych – artykuły Krzysztofa Loski (film), Arkadiusza Jabłońskiego (komunikacja międzykulturowa), Marcina Rutkowskiego (prawodawstwo dotyczące pornografii w mediach) oraz Marty -

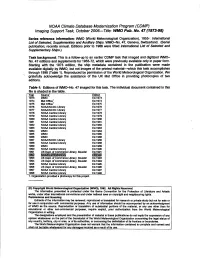

NOAA Climate Database Modernization Program (CD MP

NOAA Climate Database Modernization Program (CDMP) Imaging Support Task, October 2006--Title: WOPub. No. 47 (1973-98) Series reference information: WMO (World Meteorological Organization), 1955: lnfernafional Lisf of Selected, Supplementary and Auxiliary Ships. WMO-No. 47, Geneva, Switzerland. (Serial publication; recently annual. Editions prior to 1966 were titled lnfernafional List of Selecfed and Supplementary Ships.) Task background: This is a follow-up to an earlier CDMP task that imaged and digitized WMO- No. 47 editions and supplements for 1955-72, which were previously available only in paper form. Starting with the 1973 edition, the ship metadata contained in the publication were made available digitally by WMO, but not images of the printed material-which this task accomplishes through 1998 (Table 1). Reproduced by permission of the World Meteorological Organization. We giatefully acknowledge the assistance of the UK Met Office in providing photocopies of two editions. Table f: Editions of WMO-No. 47 imaged for this task. The individual document contained in this file is shaded in the table. -Year Source' Edition 1973 WMO Ed. 1973 1974 Metoffice' Ed. 1974 1975 Metoffice' Ed. 1975 1976 NOMNCDC Library Ed. 1976 I977 NOMNCDC Library Ed.1977 1978 NOMCentral Library Ed. 1978 1979 NOMCentral Library Ed. 1979 1980 NOMCentral Library Ed. 1980 1981 NOAA Central Library Ed.1981 1982 NOMCentral Library Ed. I982 1983 NOAA Central Library Ed.1983 1984 WMO Ed. I984 1985 WMO Ed.1985 1986 WMO Ed. 1986 1987 NOMNCDC Library Ed.1 986 1988 NOAA Central Library Ed.1988 1989 WMO Ed.1989 1990 NOAA Central Libraw Ed.1990 1991 u e Library, Boulder Ed.1991 %@E 1 EX9Z 1993 US Dept: of.Commerce Library, Boulder Ed.1993 1994 US Dew. -

The Logical Linguistics

International Journal of Latest Research in Humanities and Social Science (IJLRHSS) Volume 01 - Issue 11, www.ijlrhss.com || PP. 10-48 The Logical Linguistics: Logic of Phonemes and Morae Contained in Speech Sound Stream and the Logic of Dichotomy and Dualism equipped in Neurons and Mobile Neurons Inside the Cerebrospinal Fluid in Ventricular System Interacting for the Unconscious Grammatical Processing and Constitute Meaning of Concepts. (A Molecular Level Bio-linguistic Approach) Kumon “Kimiaki” TOKUMARU Independent Researcher Abstract: This is an interdisciplinary integration on the origins of modern human language as well as the in- brain linguistic processing mechanism. In accordance with the OSI Reference Model, the author divides the entire linguistic procedure into logical layer activities inside the speaker‟s and listener‟s brains, and the physical layer phenomena, i.e. the speech sound stream or equivalent coded signals such as texts, broadcasting, telecommunications and bit data. The entire study started in 2007, when the author visitedthe Klasies River Mouth (KRM) Caves in South Africafor the first time, the oldest modern human site in the world.The archaeological excavation in 1967- 68 (Singer Wymer 1982) confirmed that (anatomically) modern humanshad lived inside the caves duringthe period120 – 60 Ka (thousand years ago), which overlaps with the timing of language acquisition, 75 Ka (Shima 2004). Following this first visitIstarted an interdisciplinary investigation into linguistic evolution and the in- brain processing mechanism of language through reading various books and articles. The idea that the human language is digital was obtained unexpectedly. The Naked-Mole Rats (Heterocephalus glaber) are eusocial and altruistic. They live underground tunnel in tropical savanna of East Africa.