ENCYCLOPEDIA of CHINESE FILM In'>1 S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926 Hongkong Workers in an Anti-Imperialist Movement Robert JamesHorrocks Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof PhD The University of Leeds Departmentof East Asian Studies October 1994 The candidateconfirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. 11 Abstract In this thesis, I study the Guangzhou-Hongkong strike of 1925-1926. My analysis differs from past studies' suggestions that the strike was a libertarian eruption of mass protest against British imperialism and the Hongkong Government, which, according to these studies, exploited and oppressed Chinese in Guangdong and Hongkong. I argue that a political party, the CCP, led, organised, and nurtured the strike. It centralised political power in its hands and tried to impose its revolutionary visions on those under its control. First, I describe how foreign trade enriched many people outside the state. I go on to describe how Chinese-run institutions governed Hongkong's increasingly settled non-elite Chinese population. I reject ideas that Hongkong's mixed-class unions exploited workers and suggest that revolutionaries failed to transform Hongkong society either before or during the strike. My thesis shows that the strike bureaucracy was an authoritarian power structure; the strike's unprecedented political demands reflected the CCP's revolutionary political platform, which was sometimes incompatible with the interests of Hongkong's unions. I suggestthat the revolutionary elite's goals were not identical to those of the unions it claimed to represent: Hongkong unions preserved their autonomy in the face of revolutionaries' attempts to control Hongkong workers. -

Yuan Muzhi Y La Comedia Modernista De Shanghai

Yuan Muzhi y la comedia modernista de Shanghai Ricard Planas Penadés ------------------------------------------------------------------ TESIS DOCTORAL UPF / Año 2019 Director de tesis Dr. Manel Ollé Rodríguez Departamento de Humanidades Als meus pares, en Francesc i la Fina. A la meva companya, Zhang Yajing. Per la seva ajuda i comprensió. AGRADECIMIENTOS Quisiera dar mis agradecimientos al Dr. Manel Ollé. Su apoyo en todo momento ha sido crucial para llevar a cabo esta tesis doctoral. Del mismo modo, a mis padres, Francesc y Fina y a mi esposa, Zhang Yajing, por su comprensión y logística. Ellos han hecho que los días tuvieran más de veinticuatro horas. Igualmente, a mi hermano Roger, que ha solventado más de una duda técnica en clave informática. Y como no, a mi hijo, Eric, que ha sido un gran obstáculo a la hora de redactar este trabajo, pero también la mayor motivación. Un especial reconocimiento a Zheng Liuyi, mi contacto en Beijing. Fue mi ángel de la guarda cuando viví en aquella ciudad y siempre que charlamos me ofrece una versión interesante sobre la actualidad académica china. Por otro lado, agradecer al grupo de los “Aspasians” aquellos descansos entra página y página, aquellos menús que hicieron más llevadero el trabajo solitario de investigación y redacción: Xavier Ortells, Roberto Figliulo, Manuel Pavón, Rafa Caro y Sergio Sánchez. v RESUMEN En esta tesis se analizará la obra de Yuan Muzhi, especialmente los filmes que dirigió, su debut, Scenes of City Life (都市風光,1935) y su segunda y última obra Street Angel ( 马路天使, 1937). Para ello se propone el concepto comedia modernista de Shanghai, como una perspectiva alternativa a las que se han mantenido tanto en la academia china como en la anglosajona. -

New China's Forgotten Cinema, 1949–1966

NEW CHINA’S FORGOTTEN CINEMA, 1949–1966 More Than Just Politics by Greg Lewis Several years ago when planning a course on modern Chinese history as seen through its cinema, I realized or saw a significant void. I hoped to represent each era of Chinese cinema from the Leftist movement of the 1930s to the present “Sixth Generation,” but found most available subtitled films are from the post-1978 reform period. Films from the Mao Zedong period (1949–76) are particularly scarce in the West due to Cold War politics, including a trade embargo and economic blockade lasting more than two decades, and within the arts, a resistance in the West to Soviet- influenced Socialist Realism. wo years ago I began a project, Translating New China’s Cine- Phase One. Economic Recovery, ma for English-Speaking Audiences, to bring Maoist Heroic Revolutionaries, and Workers, T cinema to students and educators in the US. Several genres Peasants, and Soldiers (1949–52) from this era’s cinema are represented in the fifteen films we have Despite differences in perspective on Maoist cinema, general agree- subtitled to date, including those of heroic revolutionaries (geming ment exists as to the demarcation of its five distinctive phases (four yingxiong), workers-peasants-soldiers (gongnongbing), minority of which are represented in our program). The initial phase of eco- peoples (shaoshu minzu), thrillers (jingxian), a children’s film, and nomic recovery (1949–52) began with the emergence of the Dong- several love stories. Collectively, these films may surprise teachers bei (later Changchun) Film Studio as China’s new film capital. -

Part 1: a Brief History of the Chinese Film Industry 1896 –A Film by The

Part 1: A brief History of the Chinese Film Industry 1896 –a film by the Lumiere Brothers, premiered in Paris in December 1895, was shown in Shanghai 1897 – American showman James Ricalton showed several Edison films in Shanghai and other large cities in China. This new media was introduced as “Western shadow plays” to link to the long- standing Chinese tradition of shadow plays. These early films were shown as acts as part of variety shows. 1905 – Ren Jingfeng, owner of Fengtai Photography, bought film equipment from a German store in Beijing and made a first attempt at film production. The film “Dingjun Mountain” featured episodes from a popular Beijing opera play. The screening of this play was very successful and Ren was encouraged to make more films based on Beijing opera. Subsequently, the base of Chinese film making became the port of Shanghai because of better access to foreign capital, imported materials and technical cooperation between the Chinese and foreigners. 1907 – Beijing had the first theatre devoted exclusively to showing films 1908 – Shanghai had its first film theatre 1909 – The Asia Film Company was established as a joint venture between American businessman, Benjamin Polaski, and Zhang Shichuan and Zheng Zhengqui. Zhang and Zheng are honoured as the fathers of Chinese cinema 1913 – Zhang and Zheng made the first Chinese short feature film, which was a documentary of social customs. As female performers were not allowed to share the stage with males, all the characters were played by male performers in this narrative drama. 1913 – saw the first narrative film produced in Hong Kong WW1 cut off Shanghai’s supply of raw film from Germany, so film production stopped. -

Fei Mu's Aesthetics of Desolation in Spring In

CHAPTER FOUR BETWEEN FORGETTING AND THE REPETITIONS OF MEMORY: FEI MU’S AESTHETICS OF DESOLATION IN SPRING IN A SMALL TOWN Heroism has strength but no beauty and thus seems to lack humanity. Tragedy, however, resembles the matching of bright red with deep green: an intense and unequivocal contrast. And yet it is more exciting than truly revelatory. The reason desolation resonates far more profoundly is that it resembles the conjunction of scallion green with peach red, creating an equivocal contrast. I like writing by way of equivocal contrast because it is relatively true to life.1 Like wartime cartoonists, poets, dramatists, and other artists who traveled inland to promote the cause of resistance, the Chinese film industry was also displaced to the Nationalist interior during the War of Resistance. The Nationalist government-owned Central Film Studio (Zhongyang diangy- ing sheyingchang 中央电影摄影场) and China Motion Pictures Studio (Zhongguo dianying zhipianchang 中国电影制片厂) were relocated to Chongqing, where the government encouraged the production of docu- mentary and feature films to promote the war effort. However, political instability, inflation, supply problems, and inadequate means of distribu- tion made it difficult to create high-quality films, and both Central Film and China Motion Pictures were forced to suspend filmmaking activities between 1941 and 1943.2 Although film studios in “Orphan Island” (gudao 孤岛) Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Manchuria operated throughout most of the war, working under the watchful eye of Japanese censors, filmmakers in the occupied regions were unable to produce films that explored in depth the experiences of ordinary people in wartime. 1 Eileen Chang, “Writing of One’s Own,” p. -

Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis

arts Article Cultural “Authenticity” as a Conflict-Ridden Hypotext: Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis Zhuoyi Wang Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures, Hamilton College, Clinton, NY 13323, USA; [email protected] Received: 6 June 2020; Accepted: 7 July 2020; Published: 10 July 2020 Abstract: Disney’s Mulan (1998) has generated much scholarly interest in comparing the film with its hypotext: the Chinese legend of Mulan. While this comparison has produced meaningful criticism of the Orientalism inherent in Disney’s cultural appropriation, it often ironically perpetuates the Orientalist paradigm by reducing the legend into a unified, static entity of the “authentic” Chinese “original”. This paper argues that the Chinese hypotext is an accumulation of dramatically conflicting representations of Mulan with no clear point of origin. It analyzes the Republican-era film adaptation Mulan Joins the Army (1939) as a cultural palimpsest revealing attributes associated with different stages of the legendary figure’s millennium-long intertextual metamorphosis, including a possibly nomadic woman warrior outside China proper, a Confucian role model of loyalty and filial piety, a Sinitic deity in the Sino-Barbarian dichotomy, a focus of male sexual fantasy, a Neo-Confucian exemplar of chastity, and modern models for women established for antagonistic political agendas. Similar to the previous layers of adaptation constituting the hypotext, Disney’s Mulan is simply another hypertext continuing Mulan’s metamorphosis, and it by no means contains the most dramatic intertextual change. Productive criticism of Orientalist cultural appropriations, therefore, should move beyond the dichotomy of the static East versus the change-making West, taking full account of the immense hybridity and fluidity pulsing beneath the fallacy of a monolithic cultural “authenticity”. -

HUMA 1210: Chinese Women on Screen

HUMA 1210: Chinese Women on Screen Instructor: Daisy Yan Du Associate Professor Division of Humanities Office: Room 2369 (Lift 13-15), Academic Bldg Office phone: (852) 2358-7792 E-mail: [email protected] Office hours: by appointment only Teaching Assistant: Song HAN E-mail: [email protected] Office: Room 3001 (Lift 4), Academic Bldg Office hours: by appointment only Time & Classroom: Time: 12-14:50pm, Friday, Spring 2019 Room: LTH Required Readings: • All available online at “Files,” Canvas Course Description: This course examines Chinese women as both historical and fictional figures to unravel the convoluted relationship between history and visual representations. It follows a chronological order, beginning with women in Republican China and ending with contemporary female immigrants in the age of globalization. The changing images of women on screen go hand in hand with major cinematic movements in history, including the leftist turn in the 1930s, the rise of animation in wartime Shanghai, socialist filmmaking during the Seventeen Years (1949-1966), the birth of model opera film during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), post-1989 underground/independent filmmaking, and the globalization of cinema in contemporary China. Approaches of film analyses and gender/sexuality theories will be introduced throughout the course. All reading materials, lectures, classroom discussions, and exams are in English. Course Objectives: By the end of this semester students should be able to: • track the changing images of women in history • track -

Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema

Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema edited by Ying Zhu and Stanley Rosen Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre, 7 Tin Wan Praya Road, Aberdeen, Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hong Kong University Press 2010 Hardcover ISBN 978-962-209-175-7 Paperback ISBN 978-962-209-176-4 All rights reserved. Copyright of extracts and photographs belongs to the original sources. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the copyright owners. Printed and bound by XXXXX, Hong Kong, China Contents List of Tables vii Acknowledgements ix List of Contributors xiii Introduction 1 Ying Zhu and Stanley Rosen Part 1 Film Industry: Local and Global Markets 15 1. The Evolution of Chinese Film as an Industry 17 Ying Zhu and Seio Nakajima 2. Chinese Cinema’s International Market 35 Stanley Rosen 3. American Films in China Prior to 1950 55 Zhiwei Xiao 4. Piracy and the DVD/VCD Market: Contradictions and Paradoxes 71 Shujen Wang Part 2 Film Politics: Genre and Reception 85 5. The Triumph of Cinema: Chinese Film Culture 87 from the 1960s to the 1980s Paul Clark vi Contents 6. The Martial Arts Film in Chinese Cinema: Historicism and the National 99 Stephen Teo 7. Chinese Animation Film: From Experimentation to Digitalization 111 John A. Lent and Ying Xu 8. Of Institutional Supervision and Individual Subjectivity: 127 The History and Current State of Chinese Documentary Yingjin Zhang Part 3 Film Art: Style and Authorship 143 9. -

Bluestar Holds 2011 Centralized Purchase and Logistics Management Meeting

ISSUE 80 March 30th, 2011 Bluestar Holds 2011 Centralized Purchase and Logistics Management Meeting Bluestar Strategic Purchase Dept. luestar held its 2011 centralized purchase and logistics management meeting on March 18, where President Robert BLu and COO Mark instructed the participants from purchase departments and logistics departments of Bluestar subordinates as to how to plan for this year's purchase and logistics activities and reduce costs. At the meeting, commendations were extended to companies and individuals for their outstanding performance in centralized purchase and logistics management in 2010. Changsha Design and Research Institute Grows Stronger through Technological Innovation Zeng Jinqi hina Bluestar Changsha Design and Research in the national best engineering design award for three of CInstitute has become a domestic technology leader its design products and over 20 best engineering design and in some cases even a world leader in the development awards at the provincial or ministerial level. In 2010, the and comprehensive utilization of potassium resources institute's "construction project of technical service platform by constantly meeting the market demand and pursuing for industrialization of high and new technology for the technological innovation, enjoying technology leadership in development and comprehensive utilization of potassium the development of phosphorus resources and pyrite. It has resources in salt lake" was included in the national torch set up a good reputation and corporate image both inside program of 2010, a result of the institute's greater efforts in and outside the industry with outstanding achievements. the development and comprehensive utilization of salt lake During the 10th and 11th five-year plan periods, a 1.2 resources through innovation. -

From Textual to Historical Networks: Social Relations in the Bio-Graphical Dictionary of Republican China Cécile Armand, Christian Henriot

From Textual to Historical Networks: Social Relations in the Bio-graphical Dictionary of Republican China Cécile Armand, Christian Henriot To cite this version: Cécile Armand, Christian Henriot. From Textual to Historical Networks: Social Relations in the Bio-graphical Dictionary of Republican China. Journal of Historical Network Research, In press. halshs-03213995 HAL Id: halshs-03213995 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03213995 Submitted on 8 Jun 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ARMAND, CÉCILE HENRIOT, CHRISTIAN From Textual to Historical Net- works: Social Relations in the Bio- graphical Dictionary of Republi- can China Journal of Historical Network Research x (202x) xx-xx Keywords Biography, China, Cooccurrence; elites, NLP From Textual to Historical Networks 2 Abstract In this paper, we combine natural language processing (NLP) techniques and network analysis to do a systematic mapping of the individuals mentioned in the Biographical Dictionary of Republican China, in order to make its underlying structure explicit. We depart from previous studies in the distinction we make between the subject of a biography (bionode) and the individuals mentioned in a biography (object-node). We examine whether the bionodes form sociocentric networks based on shared attributes (provincial origin, education, etc.). -

Nora's Performance in China

Nora’s Performance in China (1914-2010): Inspiration, Communities and Political Theatre By Xiaofei Chen Master thesis Center for Ibsen Studies UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Spring semester, 2010 Acknowledgements I came to Oslo University by serendipity. When I was searching the resources for my thesis Nora’s rewriting in China(1914-1948), by accident the website of Ibsen Center jumped out. Then I came to Norway and studied at Ibsen Center. Whether in Norway or in China, many people asked me why I had chosen Ibsen studies and had come to Norway. I always said because I liked Ibsen’s plays and Norway has an Ibsen Center. It turned out that I had chosen correctly. At the Ibsen Center, professors and students from all over the world gave me lots of chances to access different ideas and insights into Ibsen studies, especially from theatre and performance aspects. I could access the original Ibsen’s texts and understand Norwegian society in Ibsen’s times, and I could watch Ibsen’s performances from different countries either in the National Theatre or through DVDs in class. Thanks to Ibsen Center for giving me the opportunity to study here, and I also want to show my appreciation for all the professors at the Ibsen Center: especially Frode Helland, Astrid Sæther, Jon Nygaard, Atle Kittang, Erika Fischer-Lichte and Nilu Kamaluddin, Julie Holledge, Knut Brynhildsvoll, who gave me the latest information about Ibsen studies through lectures and seminars. My special thanks for my professor, Jon Nygaard, who gave me the inspiration to write this topic with fresh insight. -

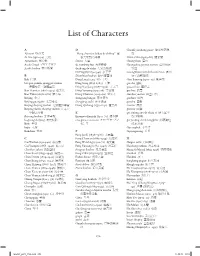

List of Characters

List of Characters A D Guanli yaoshang guize 䭉䎮喍⓮夷 Ajinomi 味の美 “Dang chuntian laidao de shihou” 䔞 ⇯ Ai Xia (1912–34) 刦曆 㗍⣑Ἦ⇘䘬㗪῁ Guan Zilan (1903–86) 斄䳓嗕 Ajinomoto 味の素 Daxue ⣏⬠ Guangzhou ⺋ⶆ Asahi Graph アサヒグラフ da yundong hui ⣏忳≽㚫 Guangzhou guomin xinwen ⺋ⶆ⚳㮹 Asahi shinbun 朝日新聞 dazhong de yishu ⣏䛦䘬喅埻 㕘倆 Di Pingzi (1879–1941) 䉬⸛⫸ Guangzhou nuzi shifan xuexiao ⺋ⶆ B Dianshizai huabao 溆䞛滳䔓⟙ ⤛⫸ⷓ䭬⬠㟉 Bali 湶 Ding Ling (1904–86) ᶩ䍚 Guo Jianying (1907–79) 悕⺢劙 baoguo yumin, qiangguo fumin Ding Song (1891-1969) ᶩあ guochi ⚳」 ᾅ⚳做㮹炻⻟⚳㮹 Ding Wenjiang (1887–1936) ᶩ㔯㰇 guocui hua ⚳䱡䔓 Bao Tianxiao (1876–1973) ⊭⣑䪹 Ding Yanyong (1902-78) ᶩ埵 guohua ⚳䔓 Bao Yahui (1898-1982) 欹Ṇ㘱 Dong Chuncai (1905–90) 吋䲼ㇵ Guohua yuekan ⚳䔓㚰↲ Beijing ⊿Ṕ dongfang bingfu 㜙㕡䕭⣓ guohuo ⚳屐 Beijing guangshe ⊿Ṕ䣦 Dongfang zazhi 㜙㕡暄娴 guoshu ⚳埻 Beijing sheying xuehui ⊿Ṕ㓅⼙⬠㚫 Dong Qichang (1555–1636) 吋℞㖴 Guotai ⚳㲘 Beiping daxue sheying xuehui ⊿⸛⣏ guoxue ⚳⬠ ⬠㓅⼙⬠㚫 E gei xinling zuo de shafa yi 䴎⽫曰⛸ Beiyang huabao ⊿㲳䔓⟙ Enomoto Kenichi (1904-70) 榎本健一 䘬㱁䘤㢭 boguang shuying 㲊㧡⼙ ero, guro, nansensu エロ・グロ・ナン gei yanjing chi de bingqilin 䴎䛤䜃⎫ Buin ิၨ センス 䘬⅘㵯㵳 bujie ᶵ㻼 Gyeongbok ઠฟ Bukchon ีᆀ F Gyeongseong ઠໜ Fang Junbi (1898–1986) 㕡⏃䑏 C Feng Chaoran (1882–1954) 楖崭䃞 H Cai Weilian (1904-40) 哉⦩ Feng Wenfeng (1900-71) 楖㔯沛 Haiguo tuzhi 㴟⚳⚾⽿ Cai Yuanpei (1868–1940) 哉⃫➡ Feng Yuxiang (1882–1948) 楖䌱䤍 Haishang fanhua 㴟ᶲ䷩厗 Chenbao fukan 㘐⟙∗↲ Fengyue huabao 桐㚰䔓⟙ Hamada Masuji (1892-1938) 浜田増治 Chen Baoyi (1893–1945) 昛㉙ᶨ Feng Zikai (1898–1975) 寸⫸ミ Hanbok ዽฟ Chen Duxiu (1879–1942) 昛䌐䥨 Fudan daxue ⽑㖎⣏⬠ Hankou 㻊⎋