Researchpaper – Theshadow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia Cár - Pozri Jurodiví/Blázni V Kristu; Rusko

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia cár - pozri jurodiví/blázni v Kristu; Rusko Georges Becker: Korunovácia cára Alexandra III. a cisárovnej Márie Fjodorovny Heslo CAR – CARI Strana 1 z 39 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia N. Nevrev: Roman Veľký prijíma veľvyslanca pápeža Innocenta III (1875) Cár kolokol - Expres: zvon z počiatku 17.st. odliaty na príkaz cára Borisa Godunova (1552-1605); mal 36 ton; bol zavesený v štvormetrovej výške a rozhojdávalo ho 12 ľudí; počas jedného z požiarov spadol a rozbil sa; roku 1654 z jeho ostatkov odlial ruský majster Danilo Danilov ešte väčší zvon; o rok neskoršie zvon praskol úderom srdca; ďalší nasledovník Cára kolokola bol odliaty v Kremli; 24 rokov videl na provizórnej konštrukcii; napokon sa našiel majster, ktorému trvalo deväť mesiacov, kým ho zdvihol na Uspenský chrám; tam zotrval do požiaru roku 1701, keď spadol a rozbil sa; dnešný Cár kolokol bol formovaný v roku 1734, ale odliaty až o rok neskoršie; plnenie formy kovom trvalo hodinu a štvrť a tavba trvala 36 hodín; keď roku 1737 vypukol v Moskve požiar, praskol zvon pri nerovnomernom ochladzovaní studenou vodou; trhliny sa rozšírili po mnohých miestach a jedna časť sa dokonca oddelila; iba tento úlomok váži 11,5 tony; celý zvon váži viac ako 200 ton a má výšku 6m 14cm; priemer v najširšej časti je 6,6m; v jeho materiáli sa okrem klasickej zvonoviny našli aj podiely zlata a striebra; viac ako 100 rokov ostal zvon v jame, v ktorej ho odliali; pred rokom 2000 poverili monumentalistu Zuraba Cereteliho odliatím nového Cára kolokola, ktorý mal odbiť vstup do nového milénia; myšlienka však nebola doteraz zrealizovaná Caracallove kúpele - pozri Rím http://referaty.atlas.sk/vseobecne-humanitne/kultura-a-umenie/48731/caracallove-kupele Heslo CAR – CARI Strana 2 z 39 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia G. -

Digitalisierter Bestand Der Graphischen Sammlung Stift Göttweig the Digitized Assets of the Graphic Collection of the Göttweig Abbey

Titelblatt BW_DUK H 09.12_: 24.09.12 15:30 Seite 1 Digitalisierter Bestand der Graphischen Sammlung Stift Göttweig The Digitized Assets of the Graphic Collection of the Göttweig Abbey Graphisches Kabinett, Inventor & Stecher: Kleiner, Salomon (1700-1761), 1744 – bezeichnet: „Musaei Contignatio superior“ Katalog zur Erschließung und Indexierung der Graphischen Sammlung Stift Göttweig Digitalisierung, Dokumentation und Archivierung Catalog of details on the development and indexing of the Graphic Print Collection of the Göttweig Abbey’s digitization, documentation and archiving Donau-Universität Krems | Zentrum für Bildwissenschaften Danube University Krems | Center for Image Science www.gssg.at (c)2012 Lehrstuhl für Bildwissenschaften / Chair Professor for Image Science & Zentrum für Bildwissenschaften / Center for Image Science Department für Kunst- und Bildwissenschaften / Department for Arts- and Image Science Donau-Universität Krems / Danube University Krems Editors: Prof. Dr. Oliver Grau, Wendy Coones M.Ed. PDF: 206 pages permanent web identifier: URI http://hdl.handle.net/10002/592 Seiten / Pages i.-vi.: I. –Impressum / About: Digitale Bilddaten und Veröffentlichungsrechte: / Digital Files and Permission for Publication: Sammlung / Collection: Mitarbeit / Team: ii. II. Inventarisierte Digitale Graphische Sammlung Göttweig: / Inventory Digital Graphic Collection Göttweig: iii. III. Online Datenbank: www.GSSG.at / Online Database: www.GSSG.at iii. IV. Projektdaten Digitalisierung: / Digitization Project Data: iv. V. Metadaten: / Metadata: v. VI. – Metadaten Abkürzung: / Metadata Abbreviations: v. VII. Inventar der Digitalisate: / Inventory of the Digitized Assets: 1-199 [i] I. IMPRESSUM / ABOUT: DIGITALE BILDDATEN UND VERÖFFENTLICHUNGSRECHTE / DIGITAL FILES AND PERMISSION FOR PUBLICATION: Donau-Universität Krems / Danube University Krems Department für Kunst- und Bildwissenschaften / Dept. for Arts- and Image Science Zentrum für Bildwissenschaften / Center for Image Science Dr. -

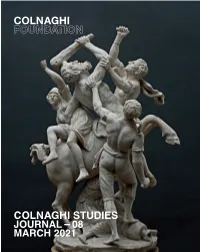

Journal 08 March 2021 Editorial Committee

JOURNAL 08 MARCH 2021 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Stijn Alsteens International Head of Old Master Drawings, Patrick Lenaghan Curator of Prints and Photographs, The Hispanic Society of America, Christie’s. New York. Jaynie Anderson Professor Emeritus in Art History, The Patrice Marandel Former Chief Curator/Department Head of European Painting and JOURNAL 08 University of Melbourne. Sculpture, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Charles Avery Art Historian specializing in European Jennifer Montagu Art Historian specializing in Italian Baroque. Sculpture, particularly Italian, French and English. Scott Nethersole Senior Lecturer in Italian Renaissance Art, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Andrea Bacchi Director, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna. Larry Nichols William Hutton Senior Curator, European and American Painting and Colnaghi Studies Journal is produced biannually by the Colnaghi Foundation. Its purpose is to publish texts on significant Colin Bailey Director, Morgan Library and Museum, New York. Sculpture before 1900, Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio. pre-twentieth-century artworks in the European tradition that have recently come to light or about which new research is Piers Baker-Bates Visiting Honorary Associate in Art History, Tom Nickson Senior Lecturer in Medieval Art and Architecture, Courtauld Institute of Art, underway, as well as on the history of their collection. Texts about artworks should place them within the broader context The Open University. London. of the artist’s oeuvre, provide visual analysis and comparative images. Francesca Baldassari Professor, Università degli Studi di Padova. Gianni Papi Art Historian specializing in Caravaggio. Bonaventura Bassegoda Catedràtic, Universitat Autònoma de Edward Payne Assistant Professor in Art History, Aarhus University. Manuscripts may be sent at any time and will be reviewed by members of the journal’s Editorial Committee, composed of Barcelona. -

Un Olor a Italia. Conexiones E Influencias En El Arte Aragonés

En este volumen se reúnen las lecciones impartidas en el último curso de la Cá- «Un olor a Italia» tedra «Goya» celebrado en noviembre del año 2018. Conexiones e Con el título «Un olor a Italia», toma- influencias en el do de una descripción de la ciudad de Zaragoza de Guzmán de Alfarache, novela arte aragonés picaresca escrita por Mateo Alemán y pu- (siglos XIV-XVIII) blicada en dos partes: la primera en Ma- drid en 1599, y la segunda en Lisboa en M.ª del Carmen Lacarra (coord.) 1604, se programó este año un nuevo curso dedicado a las conexiones e influencias italianas en el arte aragonés de los si- glos XIV a XVIII, con el estudio de obras pertenecientes al mundo de la escultura, de la pintura mural y sobre tabla, a la imprenta y al grabado, y al trabajo de las piedras fingidas llevado a cabo por un artífice de origen veneciano, Ambrosio Mariesque, en el interior de las iglesias aragonesas durante la época barroca. Destacados estudiosos de la Historia del Arte, pertenecientes a las Universidades de Barcelona, Valencia y Zaragoza parti- ciparon en esta ocasión que quiso ser, Imagen de cubierta: como otras veces, una actualización de las investigaciones dedicadas a la His- Retratos de doña Marquesa toria del Arte aragonés. Gil de Rada y Martín de Alpartir. Detalle del «Un olor a Italia» Conexiones e influencias en el arte aragonés (siglos XIV-XVIII) Retablo de la Resurrección de Cristo, Jaume Serra, 1381-1382, Museo de Zaragoza. Procede del Monasterio del Santo Sepulcro de Zaragoza. Imagen de cubierta: Retratos de doña Marquesa Gil de Rada y Martín de Alpartir. -

Pittura Haitiana Non Ha Inizio Prima Del 1945

H Haagen (Verhagen), Joris van der (Arnhem o Dordrecht 1615 - L’Aja 1669). Attivo princi- palmente all’Aja, dove è iscritto alla ghilda nel 1643, viene citato dal 1650 al 1657 ad Amsterdam, viaggia spes- so in Germania e in Olanda, dipingendo numerosi paesag- gi: Veduta di Arnhem (conservato a Carcassonne; 1649: L’Aja, Mauritshuis), Veduta del villaggio di Ilpendam (Pari- gi, Louvre), Paesaggio (Angers, mba), Paesaggio con ba- gnanti (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum), Paesaggio con il buon Samaritano (Rotterdam, bvb). Pittori come A. van de Velde e N. Berchem dipinsero le figure dei suoi paesaggi, notevoli per la limpidezza dell’atmosfera e la precisione dei dettagli. (jv). Haarlem Città olandese sulla Spaarne, non lontano dal mare, cen- tro del commercio dei tulipani nel xvii sec.; fu tra i piú notevoli centri di produzione pittorica del paese. XV secolo L’esistenza di una scuola di pittura a H nel xv sec. è attestata da Karel van Mander. I suoi confini resta- no di difficile definizione, poiché le affermazioni di que- sto storiografo non sono confermate da documenti abbon- danti. Che Dirck Bouts sia originario di H sembra certo, ma né le date del suo soggiorno nella città, né le opere che vi dipinse hanno potuto essere identificate. Si sono potuti raggruppare soltanto alcuni dipinti intorno alla Re- surrezione di Lazzaro (Berlino-Dahlem) descritta da Van Mander come opera di Aelbert van Ouwater, altro espo- nente della pittura del Quattrocento a H. Essi attestano Storia dell’arte Einaudi fedeltà alla tradizione di Van Eyck, e in parte l’influenza di Rogier van der Weyden. -

Georges De La Tour's Flea-Catcher and the Iconography of the Flea-Hunt in Seventeenth-Century Baroque Art" (2007)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2007 Georges de La Tour's Flea-Catcher and the iconography of the flea-hunt in seventeenth- century Baroque art Crissy Bergeron Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Bergeron, Crissy, "Georges de La Tour's Flea-Catcher and the iconography of the flea-hunt in seventeenth-century Baroque art" (2007). LSU Master's Theses. 462. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/462 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEORGES DE LA TOUR’S FLEA-CATCHER AND THE ICONOGRAPHY OF THE FLEA-HUNT IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY BAROQUE ART A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Crissy Bergeron B.A., Northwestern State University, 2001 May 2007 Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………...……………………iii Chapter 1 Introduction…………………….…………………………..……………………….1 2 The Flea-Catcher and Catholic Iconography……………..………………………18 3 Sexual Connotations of the Flea in Word and Image……………………….…….32 4 Conclusion……………………………………………………...…………………44 Bibliography……………………………………………………………..………………47 Vita……………………………………………………………………………………….51 ii Abstract This essay performs a comprehensive investigation of the thematic possibilities for Georges de La Tour’s Flea-Catcher (1630s-1640s) based on related artworks, religion, and emblematic, literary, and pseudo-scientific texts that may have had a bearing on it. -

View / Open Phillips Oregon 0171N 12216.Pdf

NOT DEAD BUT SLEEPING: RESURRECTING NICCOLÒ MENGHINI’S SANTA MARTINA by CAROLINE ANNE CYNTHIA PHILLIPS A THESIS Presented to the Department of the History of Art and Architecture and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2018 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Caroline Anne Cynthia Phillips Title: Not Dead but Sleeping: Resurrecting Niccolò Menghini’s Santa Martina This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture by: Dr. James Harper Chair Dr. Maile Hutterer Member Dr. Derek Burdette Member and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2018 ii © 2018 Caroline Anne Cynthia Phillips iii THESIS ABSTRACT Caroline Anne Cynthia Philips Master of Arts Department of the History of Art and Architecture June 2018 Title: Not Dead but Sleeping: Resurrecting Niccolò Menghini’s Santa Martina Niccolò Menghini’s marble sculpture of Santa Martina (ca. 1635) in the Church of Santi Luca e Martina in Rome belongs to the seventeenth-century genre of sculpture depicting saints as dead or dying. Until now, scholars have ignored the conceptual and formal concerns of the S. Martina, dismissing it as derivative of Stefano Maderno’s Santa Cecilia (1600). This thesis provides the first thorough examination of Menghini’s S. Martina, arguing that the sculpture is critically linked to the Post-Tridentine interest in the relics of early Christian martyrs. -

Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin 2012 Online Supplement

Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin 2012 online supplement 1 african art Within these lists, objects in the depart- by other media in order of prevalence. Acquisitions ments of American Decorative Arts, Dimensions are given in inches followed July 1, 2011– American Paintings and Sculpture, Asian by centimeters in parentheses; height Art, European Art, Modern and Con- precedes width. For three-dimensional June 30, 2012 temporary Art, and Prints, Drawings, sculpture and most decorative objects, and Photographs are alphabetized by such as furniture, height precedes width artist, then ordered by date, then alpha- precedes depth. For drawings, dimen- betized by title, then ordered by acces- sions are of the sheet; for relief and inta- sion number. Objects in the departments glio prints, the matrix; for planographic of African Art, Ancient Art, Art of the prints, the sheet; and for photographs, Ancient Americas, Coins and Medals, the image, unless otherwise noted. For and Indo-Pacific Art are ordered chrono- medals, weight is given in grams, axis in logically, then alphabetized by title, then clock hours, and diameter in millimeters. ordered by accession number. If an object is shaped irregularly, maxi- Circa (ca.) is used to denote that mum measurements are given. a work was executed sometime within Illustrated works are titled in bold. or around the date given. For all objects, principal medium is given first, followed 2 Christian Hand Cross Ethiopian Orthodox Tawahido Church, 1700 Christian Hand Cross Ethiopian Orthodox Tawahido Church, 18th–19th century African Art Christian Hand Cross Ethiopian Orthodox Tawahido Church Ethiopia, 1700 Wood and metal, 16 x 6½ x ⅞ in. -

Pittura Giapponese Apparen- Tati Ai Rotoli Degli Inferni (Jigokuzo-Shi)

G Gabbiani, Anton Domenico (Firenze 1652-1722). Per breve tempo presso il Sustermann e poi discepolo di Vincenzo Dandini. Assistito da previsio- ni granducali studiò a Firenze, a Roma (presso l’Accademia medicea diretta da Ciro Ferri) e a Venezia con Sebastiano Bombelli. Il risultato fu uno stile eclettico, tra il classicismo romano e il colorismo veneziano. Pittore ufficiale della corte medicea – protetto da Cosimo III e dal Gran Princi- pe Ferdinando – contribuí alla decorazione di palazzo Pitti, del teatro della Pergola e della villa di Poggio a Cajano (Apoteosi di Cosimo il Vecchio, 1698), oltre che di molti altri palazzi (Riccardi, Corsini, Acciaiuoli). Lavorò molto anche per la nobiltà e per la chiesa (cupola di San Frediano: Gloria di santa Maria Maddalena de’ Pazzi). Si distinse per i suoi sfondi di paesaggio, tra i quali notevoli quelli nelle Sto- rie di Diana a palazzo Gerini. Lasciò una quantità innume- revole di disegni – ammirati poi dal Mengs – che provano la sua tendenza fondamentalmente accademica di tradizio- ne fiorentina: in questo senso anche il suo evidente cortoni- smo di fondo non si limita ad una imitazione superficiale degli effetti piú spettacolari. A Roma conobbe anche la pit- tura del Maratta. Le sue grandi composizioni volgono spes- so verso un freddo accademismo, al contrario dei bozzetti, ritratti e paesaggi con figure. Tra i «quadri di stanza» si ri- corda qui, per particolare esito qualitativo, il Cristo comuni- ca san Pietro d’Alcantara alla presenza di santa Teresa, f. d. 1714 (Schleissheim, sgs). (eb + sr). Gabillou, Le La grotta del G (località della Dordogna, presso Sour- Storia dell’arte Einaudi zac), scoperta nel 1941, si compone di uno stretto corri- doio lungo una trentina di metri, sulle cui pareti una suc- cessione d’incisioni, ben conservate, rivela uno tra i piú importanti santuari paleolitici. -

Scripture and Scholarship in Early Modern England

SCRIPTURE AND SCHOLARSHIP IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND To my grand parents, Sarah & Leonard Hessayon and in memory of Manfred & Karla Selby Scripture and Scholarship in Early Modern England Edited by ARIEL HESSAYON Goldsmiths College, University of London, UK NICHOLAS KEENE Royal Holloway, University of London, UK © Ariel Hessayon and Nicholas Keene 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Ariel Hessayon and Nicholas Keene have asserted their moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the editors of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Gower House Suite 420 Croft Road 101 Cherry Street Aldershot Burlington, VT 05401-4405 Hampshire GU11 3HR USA England Ashgate website: http://www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Scripture and scholarship in early modern england 1. Bible – Criticism, interpretation, etc. – England – History – 17th century 2. Biblical scholars – England – History – 17th century 3. England – Intellectual life – 17th century 4. England – Religion – 17th century I. Hessayon, Ariel II. Keene, Nicholas 220.6'7'0942'09032 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Scripture and scholarship in early modern England / edited by Ariel Hessayon and Nicholas Keene. p. cm. ISBN 0-7546-3893-6 (alk. paper) 1. Bible—Criticism, interpretation, etc.—History. 2. England—Church history. I. Hessayon, Ariel. II. Keene, Nicholas. BS500.S37 2006 220'.0942—dc22 2005021015 ISBN-13: 978-0-7546-3893-3 ISBN-10: 0-7546-3893-6 Printed and bound in Great Britain by MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall. -

Le Livre Des Peintres Et Graveurs Par Michel De Marolles, Abbé De Villeloin

THE LÎBRARY BRIGHÀM YOUNG U IVERSITY * m LE LIVRE DES PEIiNTRES ET GRAVEURS 5oo papier vergé ordinaire. 5o — vergé fort. 20 — chine numérotés. 2 peaux de vélin numérotés. N° Paris. — Imp. Gauthier-Villars, 55, quai des Augustin LE LIVRE DES PEINTRES ET GRAVEURS PAR MICHEL DE MAROLLES, ABBÉ DE VILLELOIN SECONDE EDITION DE LA BIBLIOTHEQUE ELZEVIRIENNE revue et annotée par M. GEORGES DUPLESS1S PARIS PAUL DAFFIS, ÉDITEUR, Propriétaire de la Bibliothèque Elzévirienne, 9, RUE DES BEAUX -ARTS MDCCCLXXII ïH lT*i - WVO. UTAH PRÉFACE i Ton voulait recommander l'abbé de Marolles comme un littérateur, on courrait grand risque de faire rire de soi aurait un sort à près ; on peu gai, si l'on voulait envisager comme l'œuvre l'un poëte le Livrée des peintres et des gra- veurs ; si, au contraire, on regarde ce docte ibbé comme un simple historien de l'art, se ervant d'une poésie à sa façon pour expri- ner ce qu'il sait, on sera disposé à lui par- lonner la forme en faveur des renseignements [u'il fournit sur l'histoire des artistes; si Ton :onsidère son livre comme un simple recueil le notes sommaires, on sera encore porté à 'indulgence et on s'expliquera la valeur que juelques érudits y attachent. Ce travailleur, PREFACE. doué d'une fécondité singulière, a publié un grand nombre d'ouvrages, et lorsque la mort est venue le surprendre, il tenait prêtes encore beaucoup de notes qu'il avait l'intention de faire imprimer. Parmi ces travaux demeurés à l'état de projets, était une histoire générale de l'art dont nous lisons, à la fin du Cata- logue publié par l'abbé de Marolles en 1666, le plan détaillé. -

Un Siècle Bouillonnant

« JOSEPH INTERPRÉTANT LES SONGES » (ATTRIBUÉ A CLAUDE MELLAN) « VANITAS >>, PAR BIGOT Des pionniers du « réalisme », inspirés de qui ? De Manfredi, de Saraceni ou de Honthorst. précision presque « hyperréaliste », ces EXPOSITION Autour de Saraceni le Vénitien se re- fruits sur la table, cette carafe et ses reflets, groupent Guy François du Puy (« Sainte ce fromage à l'étagère; on pense au jeune Cécile et l'Ange »), Jean Leclerc de Nancy Vélasquez. Un merveilleux tableau, oui, (« •Concert nocturne »), l'anonyme auteur mais qu'a-t-il de français ? Un •bon tiers du « Marchand de poulets à barbe fleu- des rares oeuvres attribuées au « Cecco » Un siècle rie. De Honthorst le Néerlandais, italianisé viennent d'Espagne ; le peintre n'en vien- en e Gherardo della notte », procède l'éton- drait-il aussi, ou d'une région en étroite re- nant « maître à la chandelle », ce « Trufa- lation avec elle, comme les Deux-Siciles ? bouillonnant mondo » qui est l'Arlésien Trophime (ou Simon Vouet, Claude Vignon, comme Théophile) Bigot. Devant son « Saint Sébas- leur jeunesse romaine est attachante ! « Ca- tien soigné par Irène » ou son « Couron- ravagesques », ils ne le sont guère, si ce Les « caravagesques » nement d'épines », quel visiteur ne songe à n'est à l'occasion, presque par citation (l'un La Tour ? On a supposé une influence du dans sa « Diseuse de bonne aventure », du XVII' ne connaissaient Lorrain sur le Provençal ; mais si c'était l'autre dans •son « Martyre de saint Mat- pas le Caravage l'inverse ? thieu »). Applaudi dès ses quatorze ans, Autour de Manfredi, voici le « maître » passé par Londres, Constantinople et Ve- du « Jugement de Salomon », à la gravité nise, Vouet fait à Rome figure de maître.