View / Open Phillips Oregon 0171N 12216.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Franciscan Saints, Blesseds, and Feasts (To Navigate to a Page, Press Ctrl+Shift+N and Then Type Page Number)

Franciscan Saints, Blesseds, and Feasts (to navigate to a page, press Ctrl+Shift+N and then type page number) Saints St. Francis de Sales, January 29 ................................................ 3 St. Agnes of Assisi, November 19 ..........................................29 St. Francis Mary of Camporosso, September 20 ................24 St. Agnes of Prague, March 2 ...................................................6 St. Francis of Paola, April 2 ........................................................9 St. Albert Chmielowski, June 17 ............................................. 16 St. Francisco Solano, July 14 .....................................................19 St. Alphonsa of the Immaculate Conception, July 28........20 St. Giles Mary of St. Joseph, February 7 ................................4 St. Amato Ronconi, May 8 .......................................................12 St. Giovanni of Triora, February 7 ............................................4 St. Angela Merici, January 27 ................................................... 3 St. Gregory Grassi, July 8 ........................................................ 18 St. Angela of Foligno, January 7 ................................................1 St. Hermine Grivot, July 8 ....................................................... 18 St. Angelo of Acri, October 30 .............................................. 27 St. Humilis of Bisignano, November 25 .................................30 St. Anthony of Padua, June 13 ................................................ 16 St. -

Falda's Map As a Work Of

The Art Bulletin ISSN: 0004-3079 (Print) 1559-6478 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art Sarah McPhee To cite this article: Sarah McPhee (2019) Falda’s Map as a Work of Art, The Art Bulletin, 101:2, 7-28, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 Published online: 20 May 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 79 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art sarah mcphee In The Anatomy of Melancholy, first published in the 1620s, the Oxford don Robert Burton remarks on the pleasure of maps: Methinks it would please any man to look upon a geographical map, . to behold, as it were, all the remote provinces, towns, cities of the world, and never to go forth of the limits of his study, to measure by the scale and compass their extent, distance, examine their site. .1 In the seventeenth century large and elaborate ornamental maps adorned the walls of country houses, princely galleries, and scholars’ studies. Burton’s words invoke the gallery of maps Pope Alexander VII assembled in Castel Gandolfo outside Rome in 1665 and animate Sutton Nicholls’s ink-and-wash drawing of Samuel Pepys’s library in London in 1693 (Fig. 1).2 There, in a room lined with bookcases and portraits, a map stands out, mounted on canvas and sus- pended from two cords; it is Giovanni Battista Falda’s view of Rome, published in 1676. -

“Allo Illustre, E Molto Magnifico M. Alessandro De' Medici (...)”, Firenze

GIORGIO VASARI : “Allo Illustre, e Molto Magnifico M. Alessandro De’ Medici (...)”, Firenze, 6 February 1568, fol. [2] r, in: VITA DEL GRAN MICHELAGNOLO BUONARROTI. Scritta da M. Giorgio Vasari, Scrttore & Architetto Aretino . Con le sue Magnifiche Essequie stategli fatte in Fiorenza. DALL ’ ACHADEMIA DEL DISEGNO (Florenz 1568). herausgegeben und kommentiert von CHARLES DAVIS FONTES 20 [19. Oktober 2008] Zitierfähige URL: http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/artdok/volltexte/2008/639 QUELLEN UND DOKUMENTE ZU MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI – E -TEXTE , NR. 2 SOURCES AND DOCUMENTS FOR MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI – E -TEXTS , NO. 2 GIORGIO VASARI , “Allo Illustre, e Molto Magnifico M. Alessandro De’ Medici (...)”, Firenze, 6 February 1568 (Dedication), fol. [2] r, in: V I T A D E L GRAN MICHELAGNOLO BUONARROTI. Scritta da M. Giorgio Vasari, Pittore & Architetto Aretino . Con le sue Magnifiche Essequie stategli fatte in Fiorenza. DALL ’ ACHADEMIA DEL DISEGNO . Con Licenza, & Privilegio . I N F I O R E N Z A Nella Stamperia de’ Giunti 1568. FONTES 20 1 CONTENTS 3 THE TEXT 5 INTRODUCTION: VASARI , IL GRAN MICHELAGNOLO , AND ALESSANDRO DI OTTAVIANO DE ’ MEDICI 11 BIBLIOGRAPHY 12 THREE COMMENTARIES 14 OTTAVIANO DE ’ MEDICI 15 ALESSANDRO DI OTTAVIANO DE ’ MEDICI (L EONE XI) 16 “MICHELANGELO-BIBLIOGRAPHIE” 18 THE TEXT: English version 2 THE TEXT VITA DEL GRAN MICHELAGNOLO BUONARROTI. Scritta da M. Giorgio Vasari, Pittore & Architetto Aretino . Con le sue Magnifiche Essequie stategli fatte in Fiorenza. DALL ’ ACHADEMIA DEL DISEGNO . Con Licenza, & Privilegio . IN FIORENZA Nella Stamperia de’ Giunti 1568. fol. [2] r GIORGIO VASARI , “Allo Illustre, e Molto Magnifico M. Alessandro De’ Medici (...)”, Firenze, 6 February 1568 (Dedication), fol. -

Pietro Da Cortona in Nineteenth-Century Children's

The Painter and the Scullery Boy: Pietro da Cortona in Nineteenth-Century Children’s Literature* Lindsey Schneider Pietro Berrettini (1597-1669), called Pietro da Cortona, was one of the most influential artists in seventeenth-century Italy and was celebrated as the premier decorative painter of his generation, most notably for his ceiling in the Barberini Palace in Rome (1633-39). His reputation began to suffer soon after his death, however, due in large part to changing standards of taste that no longer tolerated the extravagances of the High Baroque style that he helped to develop and with which he is indelibly linked.1 In 1692 the director of the French Academy in Rome, Matthieu de La Teulière, reported back to Paris that, ‘Pietro da Cortona and his school have spread such great debauchery here, operating under the guise of virtuosity, *<+ giving everything over to the whims of their imaginations,’2 and made similar statements the following year, in which he charged Cortona, Bernini and Borromini with ruining the fine arts with their excess.3 This view endured over the ensuing centuries and the trope of the Baroque as a diseased and cancerous style – with Cortona as one of its prime vectors of transmission – became commonplace in art-theoretical literature. Nearly a century after La Teulière, Francesco Milizia vilified the same trio of artists, saying that Cortona, along with Borromini and Bernini, ‘represent a diseased taste – one that has infected a great number of artists’.4 In London around the same time, James Barry singled Cortona -

Napoli Nobilissima

RIVISTA DI ARTI, FILOLOGIA E STORIA NAPOLI NOBILISSIMA VOLUME LXXVII DELL’INTERA COLLEZIONE SETTIMA SERIE - VOLUME VI FASCICOLO I - GENNAIO - APRILE 2020 RIVISTA DI ARTI, FILOLOGIA E STORIA NAPOLI NOBILISSIMA direttore segreteria di redazione La testata di «Napoli nobilissima» è di proprietà Pierluigi Leone de Castris Stefano De Mieri della Fondazione Pagliara, articolazione Federica De Rosa istituzionale dell'Università degli Studi Suor Orsola Benincasa di Napoli. Gli articoli pubblicati direzione Gianluca Forgione su questa rivista sono stati sottoposti a valutazione Piero Craveri Gordon M. Poole rigorosamente anonima da parte di studiosi Lucio d’Alessandro Augusto Russo specialisti della materia indicati dalla Redazione. redazione referenze fotografiche ISSN 0027-7835 Rosanna Cioffi Aranjuez, Palacio Real, inv. 10022318: p. 38 Un numero € 38,00 (Estero: € 46,00) Nicola De Blasi © Archivio dell’arte/Pedicini fotografi: Abbonamento annuale € 75,00 (Estero: € 103,00) Carlo Gasparri pp. 4, 52 Gianluca Genovese Beaulieu, National Motor Museum, redazione Girolamo Imbruglia collezione Lord Montagu of Beaulieu: Università degli Studi Suor Orsola Benincasa Fondazione Pagliara, via Suor Orsola 10 Fabio Mangone pp. 19 (in alto), 20 (in alto), 41 80131 Napoli Marco Meriggi Luigi Coiro: pp. 16, 26-27 (autorizzazione [email protected] Riccardo Naldi alla pubblicazione del MiBACT-Direzione Giulio Pane regionale Musei Campania), 46-47, 49-52 amministrazione Valerio Petrarca Londra, National Gallery: p. 21 prismi editrice politecnica napoli srl via Argine 1150, 80147 Napoli Mariantonietta Picone Madrid, Real Academia de Bellas Artes Federico Rausa de San Fernando: p. 76 Pasquale Rossi Ministero per i Beni e le attività culturali Nunzio Ruggiero e per il turismo - Direzione regionale Carmela Vargas (coordinamento) Musei Campania - Fototeca: pp. -

Download the Programme for the Xvith International Congress of Celtic Studies

Logo a chynllun y clawr Cynlluniwyd logo’r XVIeg Gyngres gan Tom Pollock, ac mae’n seiliedig ar Frigwrn Capel Garmon (tua 50CC-OC50) a ddarganfuwyd ym 1852 ger fferm Carreg Goedog, Capel Garmon, ger Llanrwst, Conwy. Ceir rhagor o wybodaeth ar wefan Sain Ffagan Amgueddfa Werin Cymru: https://amgueddfa.cymru/oes_haearn_athrawon/gwrthrychau/brigwrn_capel_garmon/?_ga=2.228244894.201309 1070.1562827471-35887991.1562827471 Cynlluniwyd y clawr gan Meilyr Lynch ar sail delweddau o Lawysgrif Bangor 1 (Archifau a Chasgliadau Arbennig Prifysgol Bangor) a luniwyd yn y cyfnod 1425−75. Mae’r testun yn nelwedd y clawr blaen yn cynnwys rhan agoriadol Pwyll y Pader o Ddull Hu Sant, cyfieithiad Cymraeg o De Quinque Septenis seu Septenariis Opusculum, gan Hu Sant (Hugo o St. Victor). Rhan o ramadeg barddol a geir ar y clawr ôl. Logo and cover design The XVIth Congress logo was designed by Tom Pollock and is based on the Capel Garmon Firedog (c. 50BC-AD50) which was discovered in 1852 near Carreg Goedog farm, Capel Garmon, near Llanrwst, Conwy. Further information will be found on the St Fagans National Museum of History wesite: https://museum.wales/iron_age_teachers/artefacts/capel_garmon_firedog/?_ga=2.228244894.2013091070.156282 7471-35887991.1562827471 The cover design, by Meilyr Lynch, is based on images from Bangor 1 Manuscript (Bangor University Archives and Special Collections) which was copied 1425−75. The text on the front cover is the opening part of Pwyll y Pader o Ddull Hu Sant, a Welsh translation of De Quinque Septenis seu Septenariis Opusculum (Hugo of St. Victor). The back-cover text comes from the Bangor 1 bardic grammar. -

Giovanni LAZZONI by Cristiano Giometti - Biographical Dictionary of Italians - Volume 64 (2005)

Giovanni LAZZONI by Cristiano Giometti - Biographical Dictionary of Italians - Volume 64 (2005) The founder of a family of Carrara sculptors whose activity took place mainly in Tuscany, Rome and the Duchy of Modena from the second half of the seventeenth century, Lazzoni was born in Carrara in 1618 by Andrea (Campori). His debut at the service of the Este can be traced back with certainty to 17 November. 1645 ( Ducale palazzo ... ), when he began to receive a commission for his participation in the decorative enterprise of the Ducal palace in Sassuolo. The polyphonic choir of the workers and plastics gathered for the occasion was cleverly coordinated by Luca Colombi, who assigned to Lazzoni the execution of the four stucco statues placed in the niches of the ground floor atrium of the palace depicting the Seasons . In these same years we can also trace the two allegories of Nobility and Glory placed at the sides of the Este coat of arms placed above the illusionistic perspective frescoed by Angelo Michele Colonna and Agostino Mitelli on the entrance staircase of the same building (Riccomini). The last payment to Lazzoni for this series of interventions is recorded on the date of 3 April. 1647 ( Ducal Palace ... ); and it is very probable that, in a short span of time, he had moved to Rome, almost certainly recalled by the enticing possibilities of work offered by the numerous papal factories promoted in view of the Jubilee year. Starting from the spring of 1647, in fact, the plastic decoration of the pillars of the nave of St. -

Giovanni Battista Braccelli's Etched Devotions Before the Vatican

Giovanni Battista Braccelli’s Etched Devotions before the Vatican Bronze Saint Peter Erin Giffin, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany IN THE MID-SEVENTEENTH CENTURY, the artist Giovanni Battista Braccelli (ca. 1584–1650) created an etching of the bronze Saint Peter cult statue at the Vat- ican surrounded by devotees and votives (fig. 1).1 This previously unpublished print, titled The Bronze Saint Peter with Votives, offers a detailed representation of the devotional object in its early modern location (figs. 2–3): against the northeast pier of the crossing of Saint Peter’s Basilica, where Pope Paul V Borghese (r. 1605– 21) had installed it on May 29, 1620 (still in situ today). The print details a group of early modern visitors gathered around the sculpture—well-dressed men, women, and children to the left of the composition, and an assortment of humbler lay and religious personages to the right. At the center, two pilgrims with walking sticks in hand and broad-brimmed hats slung over their shoulders approach the foot of the sculpted Saint Peter with great reverence. The first of the two bows down to touch the top of his head to the underside of the sculpted foot in an act of extreme humility, bracing himself against the sculpture’s base as the crowd looks on with approval. Emanating up from the devotees, a series of ex-voto offerings blanket the flanking pilasters of Saint Peter’s. One can make out the barest references of standard votive imagery and objects on the sketchily rendered plaques—kneel- ing figures and canopied beds before floating apparitions—accompanied by Contact Erin Giffin at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (erin.giffin@kunstgeschichte .uni-muenchen.de). -

Grabmalskultur Und Soziale Strategien Im Frühneuzeitlichen Rom Am Beispiel Der Familie Papst Urbans VIII

Grabmalskultur und soziale Strategien im frühneuzeitlichen Rom am Beispiel der Familie Papst Urbans VIII. Barberini Autor(en): Köchli, Ulrich Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Zeitschrift für schweizerische Kirchengeschichte = Revue d'histoire ecclésiastique suisse Band (Jahr): 97 (2003) PDF erstellt am: 11.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-130330 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Grabmalskultur und soziale Strategien im frühneuzeitlichen Rom am Beispiel der Familie Papst Urbans Vili. Barberini Ulrich Köchli Wer je die römische Petersbasilika mit offenen Augen durchmessen hat, dem werden die zahlreichen, zum Teil monumentalen Grablegen vergangener Päpste in Erinnerung geblieben sein. -

View / Open Whitford Kelly Anne Ma2011fa.Pdf

PRESENT IN THE PERFORMANCE: STEFANO MADERNO’S SANTA CECILIA AND THE FRAME OF THE JUBILEE OF 1600 by KELLY ANNE WHITFORD A THESIS Presented to the Department of Art History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2011 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Kelly Anne Whitford Title: Present in the Performance: Stefano Maderno’s Santa Cecilia and the Frame of the Jubilee of 1600 This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of Art History by: Dr. James Harper Chairperson Dr. Nicola Camerlenghi Member Dr. Jessica Maier Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research & Innovation/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2011 ii © 2011 Kelly Anne Whitford iii THESIS ABSTRACT Kelly Anne Whitford Master of Arts Department of Art History December 2011 Title: Present in the Performance: Stefano Maderno’s Santa Cecilia and the Frame of the Jubilee of 1600 In 1599, in commemoration of the remarkable discovery of the incorrupt remains of the early Christian martyr St. Cecilia, Cardinal Paolo Emilio Sfondrato commissioned Stefano Maderno to create a memorial sculpture which dramatically departed from earlier and contemporary monuments. While previous scholars have considered the influence of the historical setting on the conception of Maderno’s Santa Cecilia, none have studied how this historical moment affected the beholder of the work. In 1600, the Church’s Holy Year of Jubilee drew hundreds of thousands of pilgrims to Rome to take part in Church rites and rituals. -

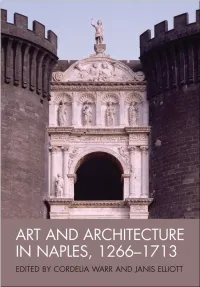

Art and Architecture in Naples, 1266-1713 / Edited by Cordelia Warr and Janis Elliott

This page intentionally left blank ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN NAPLES, 1266–1713 This page intentionally left blank ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN NAPLES, 1266–1713 NEW APPROACHES EDITED BY CORDELIA WARR AND JANIS ELLIOTT This edition first published 2010 r 2010 Association of Art Historians Originally published as Volume 31, Issue 4 of Art History Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley- Blackwell. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/ wiley-blackwell. The right of Cordelia Warr and Janis Elliott to be identified as the authors of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. -

Baroque Decorations in San Silvestro in Capite, Rome,” 1955

“Decorazioni barocche in San Silvestro in Capite a Roma,” Bollettino d’arte, XLII, 1957, 44-9 Original English version “The Baroque Decorations in San Silvestro in Capite, Rome,” 1955 (click here for first page) The Baroque Decorations in San Silvestro in Capite, Rome Irving Lavin Harvard University February, 1955 The Baroque Decorations in San Silvestro in Capite, Rome In the last quarter of the seventeenth century the Franciscan sisters of the order of Santa Clara began a thorough renovation of the church of which they had been proprietors since the thirteenth century, San Silvestro in Capite.1 The great wealth of the order made it possible to employ the ablest artists of the day, and by the time the task was completed in the early eighteenth century the church could boast of some of the major monuments of late Baroque art in Rome (Fig. 1). The great ceiling paintings of Giacinto Brandi and Ludovico Gimignani, the altarpieces of Giuseppe Chiari, the sculptures of Lorenzo Ottoni and Camillo Rusconi, and the facade by Domenico de′ Rossi, contribute to make the church’s decorations indispensable for an understanding of the stylistic development of the period. Knowledge of this contribution, however, has been severely limited by an almost exclusive dependence on the sparse notices given in early biographers and guide books, such as Pascoli and Titi. It is extremely fortunate therefore in that the archives of the convent which contain the documents relating to the decorations are still preserved in the Archivio di Stato of Rome. The most important of these documents are gathered together and transcribed in the Appendix to this notice.2 They permit a nearly complete reconstruction of the history of the decorations (Fig.