UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mongol Aristocrats and Beyliks in Anatolia

MONGOL ARISTOCRATS AND BEYLIKS IN ANATOLIA. A STUDY OF ASTARĀBĀDĪ’S BAZM VA RAZM* Jürgen Paul Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg Abstract This paper is about beyliks – political entities that include at least one town (or a major fortress or both), its agricultural hinterland and a (large) amounts of pasture. It is also about Mongols in Anatolia in the beylik period (in particular the second half of the 14th century) and their leading families some of whom are presented in detail. The paper argues that the Eretna sultanate, the Mongol successor state in Anatolia, underwent a drawn-out fission process which resulted in a number of beyliks. Out of this number, at least one beylik had Mongol leaders. Besides, the paper argues that Mongols and their leading families were much more important in this period than had earlier been assumed. arge parts of Anatolia came under Mongol rule earlier than western Iran. The Mongols had won a resounding victory over the Rum L Seljuqs at Köse Dağ in 1243, and Mongols then started occupying winter and summer pastures in Central and Eastern Anatolia, pushing the Turks and Türkmens to the West and towards the coastal mountain ranges. Later, Mongol Anatolia became part of the Ilkhanate, and this province was one of the focal points of Ilkhanid politics and intrigues.1 The first troops, allegedly three tümens, had already been dispatched to Anatolia by ———— * Research for this paper was conducted in the framework of Sonderforschungsbereich 586 (“Differenz und Integration”, see www.nomadsed.de), hosted by the universities at Halle-Wittenberg and Leipzig and funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. -

Historia Scribere 13 (2021)

historia scribere 13 (2021) The Beginnings of an Empire. The Transformation of the Ottoman State into an Empire, demonstrated at the example of Grand Vizier Mahmud Pasha’s life and accomplishments Vera Flatz Kerngebiet: Neuzeit eingereicht bei: Yasir Yilmaz, MA PhD und Univ.-Prof. Dr. Stefan Ehrenpreis eingereicht im: WiSe 2019/20 Rubrik: Seminar-Arbeit Abstract The Beginnings of an Empire. The Transformation of the Ottoman State into an Empire, demonstrated at the example of Grand Vizier Mahmud Pasha’s life and accomplishments The following seminar paper deals with Grand Vizier Mahmud Pasha’s life and the processes that turned an Ottoman principality into the Ottoman Empire. Starting with Sultan Mehmed’s II appointment in 1444, important practic- es such as the nomination of a grand vizier changed significantly. Moreover, Mehmed II built a new palace which reflected the new imperial self-percep- tion, a new code of law was installed, and the empire was centralised. All these developments become especially visible in the life of Grand Vizier Mahmud Pasha Angelovic. The paper examines secondary literature as well as contem- porary sources of Kritobolous and Ibn Khaldun. Sources on Mahmud Pasha’s life are rare and need to be analysed with caution as his posthumous legend influenced the production of literature about his life. 1. Introduction Mahmud Pasha Angelovic, born at the beginning of the 15th century in a town in Ser- bia, became one of the most influential grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire. How did that happen? In 1453, Mehmed II conquered Constantinople and made it the capital of one of the biggest empires of the early modern period. -

Phd 15.04.27 Versie 3

Promotor Prof. dr. Jan Dumolyn Vakgroep Geschiedenis Decaan Prof. dr. Marc Boone Rector Prof. dr. Anne De Paepe Nederlandse vertaling: Een Spiegel voor de Sultan. Staatsideologie in de Vroeg Osmaanse Kronieken, 1300-1453 Kaftinformatie: Miniature of Sultan Orhan Gazi in conversation with the scholar Molla Alâeddin. In: the Şakayıku’n-Nu’mâniyye, by Taşköprülüzâde. Source: Topkapı Palace Museum, H1263, folio 12b. Faculteit Letteren & Wijsbegeerte Hilmi Kaçar A Mirror for the Sultan State Ideology in the Early Ottoman Chronicles, 1300- 1453 Proefschrift voorgelegd tot het behalen van de graad van Doctor in de Geschiedenis 2015 Acknowledgements This PhD thesis is a dream come true for me. Ottoman history is not only the field of my research. It became a passion. I am indebted to Prof. Dr. Jan Dumolyn, my supervisor, who has given me the opportunity to take on this extremely interesting journey. And not only that. He has also given me moral support and methodological guidance throughout the whole process. The frequent meetings to discuss the thesis were at times somewhat like a wrestling match, but they have always been inspiring and stimulating. I also want to thank Prof. Dr. Suraiya Faroqhi and Prof. Dr. Jo Vansteenbergen, for their expert suggestions. My colleagues of the History Department have also been supportive by letting me share my ideas in development during research meetings at the department, lunches and visits to the pub. I would also like to sincerely thank the scholars who shared their ideas and expertise with me: Dimitris Kastritsis, Feridun Emecen, David Wrisley, Güneş Işıksel, Deborah Boucayannis, Kadir Dede, Kristof d’Hulster, Xavier Baecke and many others. -

Ottoman Holy War to the North of the Danube Full Article Language: En Indien Anders: Engelse Articletitle: 0

_full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien B2 voor dit chapter en nul 0 in hierna): 0 _full_articletitle_deel (kopregel rechts, vul hierna in): Ottoman Holy War to the North of the Danube _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 54 Chapter 3 Chapter 3 Ottoman Holy War to the North of the Danube 1 Efforts to the Way of Allah Initially, as vassals of the Seljukid sultans, the Anatolian beys, including the fledging Ottoman dynasty, accompanied their suzerains in holy campaigns (gaza) against Byzantine territories.1 Adopting the ideology of cihad, the Ot toman sultans assumed for themselves the task of leaders of the holy war against infidels of Southeastern Europe. This idea was directly and most cate gorically declared in “letters of conquest” (fetihnames), accounts of victorious campaigns against unbelievers, distributed both domestically and abroad by the sultans. The most relevant examples of this genre are to be found in Meh med II’s statements in letters sent to Muslim rulers.2 Furthermore, both Byzan tine and Ottoman sources indicate that sultans were conscious of their obligation to conduct cihad. For instance, in 1421, after Mehmed I’s death, as Nişancı Mehmed paşa informs us, his son, Gazi Sultan Murad Han, came to the imperial throne. Murad Han did not abandon but rather followed the right way, hoisted the banners of the holy campaign and the holy war (gaza ü-cihad bayraklarını yücelten) and confided in the glorious Allah.3 Step by step, but especially after the conquest of Arab territories, the image of sultans as leaders of holy wars was recognized across the Muslim world.4 In the sixteenth century, stereotypes dominated the image of the sultan as a holy warrior. -

Mighty Guests of the Throne Note on Transliteration

Sultan Ahmed III’s calligraphy of the Basmala: “In the Name of God, the All-Merciful, the All-Compassionate” The Ottoman Sultans Mighty Guests of the Throne Note on Transliteration In this work, words in Ottoman Turkish, including the Turkish names of people and their written works, as well as place-names within the boundaries of present-day Turkey, have been transcribed according to official Turkish orthography. Accordingly, c is read as j, ç is ch, and ş is sh. The ğ is silent, but it lengthens the preceding vowel. I is pronounced like the “o” in “atom,” and ö is the same as the German letter in Köln or the French “eu” as in “peu.” Finally, ü is the same as the German letter in Düsseldorf or the French “u” in “lune.” The anglicized forms, however, are used for some well-known Turkish words, such as Turcoman, Seljuk, vizier, sheikh, and pasha as well as place-names, such as Anatolia, Gallipoli, and Rumelia. The Ottoman Sultans Mighty Guests of the Throne SALİH GÜLEN Translated by EMRAH ŞAHİN Copyright © 2010 by Blue Dome Press Originally published in Turkish as Tahtın Kudretli Misafirleri: Osmanlı Padişahları 13 12 11 10 1 2 3 4 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the Publisher. Published by Blue Dome Press 535 Fifth Avenue, 6th Fl New York, NY, 10017 www.bluedomepress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available ISBN 978-1-935295-04-4 Front cover: An 1867 painting of the Ottoman sultans from Osman Gazi to Sultan Abdülaziz by Stanislaw Chlebowski Front flap: Rosewater flask, encrusted with precious stones Title page: Ottoman Coat of Arms Back flap: Sultan Mehmed IV’s edict on the land grants that were deeded to the mosque erected by the Mother Sultan in Bahçekapı, Istanbul (Bottom: 16th century Ottoman parade helmet, encrusted with gems). -

The Making of Sultan Süleyman: a Study of Process/Es of Image-Making and Reputation Management

THE MAKING OF SULTAN SÜLEYMAN: A STUDY OF PROCESS/ES OF IMAGE-MAKING AND REPUTATION MANAGEMENT by NEV ĐN ZEYNEP YELÇE Submitted to the Institute of Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Sabancı University June, 2009 © Nevin Zeynep Yelçe 2009 All Rights Reserved To My Dear Parents Ay şegül and Özer Yelçe ABSTRACT THE MAKING OF SULTAN SÜLEYMAN: A STUDY OF PROCESS/ES OF IMAGE-MAKING AND REPUTATION MANAGEMENT Yelçe, Nevin Zeynep Ph.D., History Supervisor: Metin Kunt June 2009, xv+558 pages This dissertation is a study of the processes involved in the making of Sultan Süleyman’s image and reputation within the two decades preceding and following his accession, delineating the various phases and aspects involved in the making of the multi-layered image of the Sultan. Handling these processes within the framework of Sultan Süleyman’s deeds and choices, the main argument of this study is that the reputation of Sultan Süleyman in the 1520s was the result of the convergence of his actions and his projected image. In the course of this study, main events of the first ten years of Sultan Süleyman’s reign are conceptualized in order to understand the elements employed first in making a Sultan out of a Prince, then in maintaining and enhancing the sultanic image and authority. As such, this dissertation examines the rhetorical, ceremonial, and symbolic devices which came together to build up a public image for the Sultan. Contextualized within a larger framework in terms of both time and space, not only the meaning and role of each device but the way they are combined to create an image becomes clearer. -

5989 Turcica 35 09 Reindl

Hedda REINDL-KIEL 247 THE TRAGEDY OF POWER THE FATE OF GRAND VEZIRS ACCORDING TO THE MENAKIBNAME-I MAHMUD PA≤A-I VELI bhorrence of tyranny and bloodthirsty despotism is, according to A 1 Joseph von Hammer , a prominent leitmotiv in the anonymous Mena- kıbname-i Mahmud Pa≥a. Hammer remarks, though, that its text cannot serve as a historical source, but is rather a kind of coffeehouse literature (lowbrow narratives presented by a story teller). Following this verdict, scholars did not show any particular interest in the menakıb for a lengthy period, although the text was printed in Turkey in the second half of the 19th century2. In 1854 an edition (using the manuscript Dresden Cod. turc. 181 and one of the Berlin manuscripts) with a French translation appeared in Friedrich Heinrich Dieterici's Chrestomatie Ottomane3, but this served largely didactic purposes. Thus, the view of scholars did not change, and Franz Babinger remarked as late as 1927 in his Geschichts- schreiber der Osmanen that the menakıb were of no historical value4. In 1949, Halil Inalcık and Mevlûd Oguz introduced a newly-found “∞gazavat-ı Sultan Murad∞”, which contained at the end an incomplete Dr. Hedda REINDL-KIEL Seminar für Orientalische Sprachen, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, Nassestr. 2 D-53113 Bonn, Germany. 1 Joseph von HAMMER, Geschichte des Osmanischen Reiches, vol. IX, Pest 1833 (reprint∞: Graz 1963), p. 238, no 116. 2 Niyazi Ahmed BANOGLU, Mahmud Pa≥a∞—∞Hayatı ve ≤ehadeti∞—(Camilerimiz ve Bâniler), Istanbul, 1970 (Gür Kitapevi), p. 8. 3 Berlin, p. 1-18 (Ottoman text), 63-81 (French translation). -

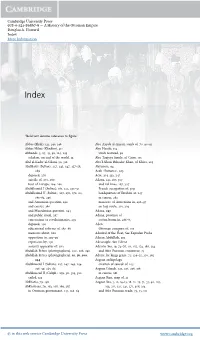

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89867-6 — a History of the Ottoman Empire Douglas A

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89867-6 — A History of the Ottoman Empire Douglas A. Howard Index More Information Index “Bold text denotes reference to figure” Abbas (Shah), 121, 140, 148 Abu Ayyub al-Ansari, tomb of, 70, 90–91 Abbas Hilmi (Khedive), 311 Abu Hanifa, 114 Abbasids, 3, 27, 45, 92, 124, 149 tomb restored, 92 scholars, on end of the world, 53 Abu Taqiyya family, of Cairo, 155 Abd al-Kader al-Gilani, 92, 316 Abu’l-Ghazi Bahadur Khan, of Khiva, 265 Abdülaziz (Sultan), 227, 245, 247, 257–58, Abyssinia, 94 289 Aceh (Sumatra), 203 deposed, 270 Acre, 214, 233, 247 suicide of, 270, 280 Adana, 141, 287, 307 tour of Europe, 264, 266 and rail lines, 287, 307 Abdülhamid I (Sultan), 181, 222, 230–31 French occupation of, 309 Abdülhamid II (Sultan), 227, 270, 278–80, headquarters of Ibrahim at, 247 283–84, 296 in census, 282 and Armenian question, 292 massacre of Armenians in, 296–97 and census, 280 on hajj route, 201, 203 and Macedonian question, 294 Adana, 297 and public ritual, 287 Adana, province of concessions to revolutionaries, 295 cotton boom in, 286–87 deposed, 296 Aden educational reforms of, 287–88 Ottoman conquest of, 105 memoirs about, 280 Admiral of the Fleet, See Kapudan Pasha opposition to, 292–93 Adnan Abdülhak, 319 repression by, 292 Adrianople. See Edirne security apparatus of, 280 Adriatic Sea, 19, 74–76, 111, 155, 174, 186, 234 Abdullah Frères (photographers), 200, 288, 290 and Afro-Eurasian commerce, 74 Abdullah Frères (photographers), 10, 56, 200, Advice for kings genre, 71, 124–25, 150, 262 244 Aegean archipelago -

Yavuz Sultan Selim'in Taht Mücadelesi

YAVUZ SULTAN SELİM’İN TAHT MÜCADELESİ Doç. Dr. Faruk SÖYLEMEZ∗ Öz II. Bayezid’in saltanatının sonlarına doğru hastalığı ve yaşlılığından dolayı devlet işleriyle ilgilenememesi sonucunda Osmanlı devlet yönetiminde meydana gelen zafiyet, birtakım olayların meydana gelmesine sebep olmuştur. Osmanlı tahtında meydana gelebilecek boşluğu doldurmak için şehzadelerin her biri İstanbul’a doğru harekete geçti. Böylece Şehzade Ahmed ile Şehzade Selim arasında taht mücadelesi başlamış oldu. Veziriazam Ali Paşa ve Şehzade Şehinşah’ın ölümü II. Bayezid’i son derece üzmüş ve hastalığının artmasına neden olmuştur. Bunun üzerine Sultan Bayezid devlet yönetiminin daha da kötüye gitmemesi için saltanattan çekilme kararı aldı. II. Bayezid şehzadeler arasındaki bu çekişme sürecinde Şehzade Selim’in Osmanlı sultanı olacak kabiliyette olduğunu müşahede etmiş ve ülkeyi içinde bulunduğu bunalımdan ancak onun kurtaracağına kanaat getirdikten sonra onu İstanbul’a davet ederek tahtı kendisine bırakmıştır. Anahtar Kelimeler: II. Bayezid, Şehzade Selim, Şehzade Ahmed, Taht, İstanbul. Yavuz Sultan Selim’s Struggle For The Throne Abstract Aged Bayezid II who suffered with some diseases, became an incapable sultan in recent years of his reign to rule the country. Sultan’s absence of power weakened his rule and created serious problems in the Ottoman Empire. Bayezid’s situation triggered competition between his sons for the throne. Princes left their sanjacks for İstanbul to grab the imperial power which could possibly fade at any time with sultan’s death. Princes Ahmed and Selim involved into a bitter fight. Death of Grand vizier Ali Pasha and Prince Şehinşah pushed the sultan into a grim sorrow and this aggravated his illness. Eventually, Sultan decided for self-abdication not to cause further problems. -

The Urbanization and Ottomanization of the Halvetiye Sufi Order by the City of Amasya in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

The City as a Historical Actor: The Urbanization and Ottomanization of the Halvetiye Sufi Order by the City of Amasya in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries By Hasan Karatas A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Hamid Algar, Chair Professor Leslie Peirce Professor Beshara Doumani Professor Wali Ahmadi Spring 2011 The City as a Historical Actor: The Urbanization and Ottomanization of the Halvetiye Sufi Order by the City of Amasya in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries ©2011 by Hasan Karatas Abstract The City as a Historical Actor: The Urbanization and Ottomanization of the Halvetiye Sufi Order by the City of Amasya in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries by Hasan Karatas Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Hamid Algar, Chair This dissertation argues for the historical agency of the North Anatolian city of Amasya through an analysis of the social and political history of Islamic mysticism in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries Ottoman Empire. The story of the transmission of the Halvetiye Sufi order from geographical and political margins to the imperial center in both ideological and physical sense underlines Amasya’s contribution to the making of the socio-religious scene of the Ottoman capital at its formative stages. The city exerted its agency as it urbanized, “Ottomanized” and catapulted marginalized Halvetiye Sufi order to Istanbul where the Ottoman socio-religious fabric was in the making. This study constitutes one of the first broad-ranging histories of an Ottoman Sufi order, as a social group shaped by regional networks of politics and patronage in the formative fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. -

The Sons of Bayezid the Ottoman Empire and Its Heritage

The Sons of Bayezid The Ottoman Empire and its Heritage Politics, Society and Economy Edited by Suraiya Faroqhi and Halil Inalcik Associate Board Firket Adanir · Idris Bostan · Amnon Cohen · Cornell Fleischer Barbara Flemming · Alexander de Groot · Klaus Kreiser Hans Georg Majer · Irène Mélikoff · Ahmet Ya¸sarOcak Abdeljelil Temimi · Gilles Veinstein · Elizabeth Zachariadou VOLUME 38 The Sons of Bayezid Empire Building and Representation in the Ottoman Civil War of 1402–1413 By Dimitris J. Kastritsis LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 On the cover: Lokman, Hünername (1584–1588), detail of miniature showing Mehmed Çelebi’s 1403 enthronement in Bursa. Topkapı Palace Library, MS. Hazine 1523, folio 112b. Reprinted by permission. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A C.I.P. record for this book is available from the Library of Congress ISSN 1380-6076 ISBN 978 90 04 15836 8 Copyright 2007 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in aretrievalsystem,ortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans,electronic,mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands To the memory of my parents By force of armes stout Mahomet his father’s kingdome gaines, And doth the broken state thereof repaire with restlesse paines. -

Leer Artículo Completo

REAL ACADEMIA MATRITENSE DE HERÁLDICA Y GENEALOGÍA La Casa de Osmán. La sucesión de los Sultanes Otomanos tras la caída del Imperio. Por José María de Francisco Olmos Académico de Número MADRID MMIX José María de Francisco Olmos A raíz de la reciente muerte en Estambul el 23 de septiembre pasado (2009) de Ertugrul Osman V, jefe de la Casa de Osmán o de la Casa Imperial de los Otomanos, parece apropiado hacer unos comentarios sobre esta dinastía turca y musulmana que fue sin duda una de las grandes potencias del mundo moderno. Sus orígenes son medievales y se encuentran en una tribu turca (los ughuz de Kayi) que emigró desde las tierras del Turquestán hacia occidente durante el siglo XII. Su líder, Suleyman, los llevó hasta Anatolia hacia 1225, y su hijo Ertugrul (m.1288) pasó a servir a los gobernantes seljúcidas de la zona, recibiendo a cambio las tierras de Senyud (en Frigia), entrando así en contacto directo con los bizantinos. Osmán, hijo de Ertugrul, fue nombrado Emir por Alaeddin III, sultán seljúcida de Icconium (Konya) y cuando el poder de los seljúcidas de Rum desapareció (1299), Osmán se convirtió en soberano independiente iniciando así la dinastía otomana, o de los turcos osmanlíes. Osmán (m. 1326) y sus descendientes no hicieron sino aumentar su territorio y consolidar su poder en Anatolia. Su hijo Orján (m.1359) conquistó Brussa, a la que convirtió en su capital, organizó la administración, creó moneda propia y reorganizó al ejército (creó el famoso cuerpo de jenízaros), en Brussa construyó un palacio cuya puerta principal se denominaba la Sublime Puerta, nombre que luego se dio al poder imperial otomano hasta su desaparición.