Leer Artículo Completo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

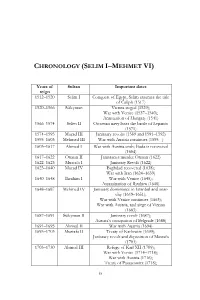

Selim I–Mehmet Vi)

CHRONOLOGY (SELIM I–MEHMET VI) Years of Sultan Important dates reign 1512–1520 Selim I Conquest of Egypt, Selim assumes the title of Caliph (1517) 1520–1566 Süleyman Vienna sieged (1529); War with Venice (1537–1540); Annexation of Hungary (1541) 1566–1574 Selim II Ottoman navy loses the battle of Lepanto (1571) 1574–1595 Murad III Janissary revolts (1589 and 1591–1592) 1595–1603 Mehmed III War with Austria continues (1595– ) 1603–1617 Ahmed I War with Austria ends; Buda is recovered (1604) 1617–1622 Osman II Janissaries murder Osman (1622) 1622–1623 Mustafa I Janissary Revolt (1622) 1623–1640 Murad IV Baghdad recovered (1638); War with Iran (1624–1639) 1640–1648 İbrahim I War with Venice (1645); Assassination of İbrahim (1648) 1648–1687 Mehmed IV Janissary dominance in Istanbul and anar- chy (1649–1651); War with Venice continues (1663); War with Austria, and siege of Vienna (1683) 1687–1691 Süleyman II Janissary revolt (1687); Austria’s occupation of Belgrade (1688) 1691–1695 Ahmed II War with Austria (1694) 1695–1703 Mustafa II Treaty of Karlowitz (1699); Janissary revolt and deposition of Mustafa (1703) 1703–1730 Ahmed III Refuge of Karl XII (1709); War with Venice (1714–1718); War with Austria (1716); Treaty of Passarowitz (1718); ix x REFORMING OTTOMAN GOVERNANCE Tulip Era (1718–1730) 1730–1754 Mahmud I War with Russia and Austria (1736–1759) 1754–1774 Mustafa III War with Russia (1768); Russian Fleet in the Aegean (1770); Inva- sion of the Crimea (1771) 1774–1789 Abdülhamid I Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774); War with Russia (1787) -

Explore Centuries of Intellectual and Cultural Links Between the Middle East and Europe

Winner of the 2018 PROSE Awards: R.R. Hawkins Award for excellence in scholarly publishing Explore centuries of intellectual and cultural links between the Middle East and Europe “This is a beautiful and fascinating collection primarily for scholars and researchers with a deep interest in the influence of the Middle East on the West.” Library Journal The Arcadian Library’s rare ancient manuscripts, early books and incunabula, documents, maps, and printed books tell the story of the shared heritage of Europe and the Middle East across a millennium. NEW Europe and the Ottoman World: Diplomacy and International Relations Comprising 35,500 facsimile images covering the period from 1475 to 1877, highlights include: • Unique illuminated and signed vellum letters from • A collection of 18th century anti-Turkish propaganda King James I to Sultan Osman II and from King pamphlets, providing insight into the history of Charles I to the Grand Vizier of Sultan Murad IV, Islamophobia in Europe. demonstrating attempts to open up new trade routes between Britain and the Middle East. • The Stopford Papers: an unstudied archive of official papers, letters and briefings sent to Admiral Sir Robert • A pair of fermans signed by Sultan Abdulmejid I Stopford, Commander-in-Chief of the British Mediterranean awarding the highest honours of the Ottoman Empire Fleet between 1837 and 1841, including his complete to the French diplomat Charles Joseph Tissot, together correspondence with the foreign secretary Viscount with signed documents by Napoleon III giving Palmerston during the second Egyptian-Ottoman War. permission for him to wear the award. Available To register for a free 30-day institutional trial, email: via perpetual access Americas: [email protected] UK, Europe, Middle East, Africa, Asia: [email protected] Australia and New Zealand: [email protected] www.arcadianlibraryonline.com. -

Mongol Aristocrats and Beyliks in Anatolia

MONGOL ARISTOCRATS AND BEYLIKS IN ANATOLIA. A STUDY OF ASTARĀBĀDĪ’S BAZM VA RAZM* Jürgen Paul Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg Abstract This paper is about beyliks – political entities that include at least one town (or a major fortress or both), its agricultural hinterland and a (large) amounts of pasture. It is also about Mongols in Anatolia in the beylik period (in particular the second half of the 14th century) and their leading families some of whom are presented in detail. The paper argues that the Eretna sultanate, the Mongol successor state in Anatolia, underwent a drawn-out fission process which resulted in a number of beyliks. Out of this number, at least one beylik had Mongol leaders. Besides, the paper argues that Mongols and their leading families were much more important in this period than had earlier been assumed. arge parts of Anatolia came under Mongol rule earlier than western Iran. The Mongols had won a resounding victory over the Rum L Seljuqs at Köse Dağ in 1243, and Mongols then started occupying winter and summer pastures in Central and Eastern Anatolia, pushing the Turks and Türkmens to the West and towards the coastal mountain ranges. Later, Mongol Anatolia became part of the Ilkhanate, and this province was one of the focal points of Ilkhanid politics and intrigues.1 The first troops, allegedly three tümens, had already been dispatched to Anatolia by ———— * Research for this paper was conducted in the framework of Sonderforschungsbereich 586 (“Differenz und Integration”, see www.nomadsed.de), hosted by the universities at Halle-Wittenberg and Leipzig and funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. -

Animal Welfare and the Protection of Draft Animals in the Ottoman Fatwa¯ Literature and Legislation

religions Article Be Gentle to Them: Animal Welfare and the Protection of Draft Animals in the Ottoman Fatwa¯ Literature and Legislation Necmettin Kızılkaya Faculty of Divinity, Istanbul University, 34452 Istanbul,˙ Turkey; [email protected] Received: 5 August 2020; Accepted: 16 October 2020; Published: 20 October 2020 Abstract: Animal studies in the Islamic context have greatly increased in number in recent years. These studies mostly examine the subject of animal treatment through the two main sources of Islam, namely, the Qur’an and the traditions of the Prophet Muhammad. Some studies that go beyond these two sources examine the subject of animal treatment through the texts of various disciplines, especially those of Islamic jurisprudence and law. Although these two research approaches offer a picture of how animal treatment is perceived in Islamic civilization, it is still not a full one. Other sources, such as fatwa¯ books and archive documents, should be used to fill in the gaps. By incorporating these into the pool of research, we will be better enabled to understand how the principles expressed in the main sources of Islam are reflected in daily life. In this article, I shall examine animal welfare and ( animal protection in the Ottoman context based on the fataw¯ a¯ of Shaykh al-Islam¯ Ebu’s-Su¯ ud¯ Efendi and archival documents. Keywords: animal welfare; animal protection; draft animals; Ottoman Legislation; Fatwa;¯ Ebussuud¯ Efendi In addition to the foundational sources of Islam and the main texts of various disciplines, the use of fatwa¯ (plural: fataw¯ a¯) collections and archival documents will shed light on an accurate understanding of Muslim societies’ perspectives on animals. -

Phd 15.04.27 Versie 3

Promotor Prof. dr. Jan Dumolyn Vakgroep Geschiedenis Decaan Prof. dr. Marc Boone Rector Prof. dr. Anne De Paepe Nederlandse vertaling: Een Spiegel voor de Sultan. Staatsideologie in de Vroeg Osmaanse Kronieken, 1300-1453 Kaftinformatie: Miniature of Sultan Orhan Gazi in conversation with the scholar Molla Alâeddin. In: the Şakayıku’n-Nu’mâniyye, by Taşköprülüzâde. Source: Topkapı Palace Museum, H1263, folio 12b. Faculteit Letteren & Wijsbegeerte Hilmi Kaçar A Mirror for the Sultan State Ideology in the Early Ottoman Chronicles, 1300- 1453 Proefschrift voorgelegd tot het behalen van de graad van Doctor in de Geschiedenis 2015 Acknowledgements This PhD thesis is a dream come true for me. Ottoman history is not only the field of my research. It became a passion. I am indebted to Prof. Dr. Jan Dumolyn, my supervisor, who has given me the opportunity to take on this extremely interesting journey. And not only that. He has also given me moral support and methodological guidance throughout the whole process. The frequent meetings to discuss the thesis were at times somewhat like a wrestling match, but they have always been inspiring and stimulating. I also want to thank Prof. Dr. Suraiya Faroqhi and Prof. Dr. Jo Vansteenbergen, for their expert suggestions. My colleagues of the History Department have also been supportive by letting me share my ideas in development during research meetings at the department, lunches and visits to the pub. I would also like to sincerely thank the scholars who shared their ideas and expertise with me: Dimitris Kastritsis, Feridun Emecen, David Wrisley, Güneş Işıksel, Deborah Boucayannis, Kadir Dede, Kristof d’Hulster, Xavier Baecke and many others. -

US Risks Further Clashes As Syrian Boot Print Broadens News & Analysis

May 28, 2017 9 News & Analysis Syria US risks further clashes as Syrian boot print broadens Simon Speakman Cordall Tunis ondemnation, criticism and, inevitably, escalation have quickly followed a US air strike against an appar- ently Iranian-backed mili- Ctia convoy near Syria’s border with Jordan and Iraq. The clash has, at least, provided analysts with some indication of American aspirations in Syria and, as the United States increases its military commitment in the area, some indication of the risks it runs of banging heads with other interna- tional actors active on Syria’s battle- scarred ground. Fars reported, “thousands of Hezbollah troops were sent to al-Tanf passageway at Iraq- Syria bordering areas.” US commanders said the convoy of Iranian-supported militia ignored numerous calls for it to halt as it Not without risks. A US-backed Syrian fighter stands on a vehicle with heavy automatic machine gun (L) next to an American soldier moved towards coalition positions who stands on an armoured vehicle at the Syrian-Iraqi crossing border point of al-Tanf. (AP) at al-Tanf, justifying the strike that destroyed a number of vehicles and killed several militiamen. agency, referred to a British, Jorda- is the military is much more likely tion to the “several hundred” special the US decision to directly arm the However, for Iran and its allies in nian and US plot to create a buffer to improvise and this decision to hit operations troops present near ISIS’s Kurds and to conduct the air strike Moscow and Damascus, the strike zone in the area, like that at the Go- the regime may have been taken at de facto capital of Raqqa, gathering against Hezbollah forces threatening marked an aerial “aggression” by lan Heights and leading ultimately to the lower levels. -

1 the Turks and Europe by Gaston Gaillard London: Thomas Murby & Co

THE TURKS AND EUROPE BY GASTON GAILLARD LONDON: THOMAS MURBY & CO. 1 FLEET LANE, E.C. 1921 1 vi CONTENTS PAGES VI. THE TREATY WITH TURKEY: Mustafa Kemal’s Protest—Protests of Ahmed Riza and Galib Kemaly— Protest of the Indian Caliphate Delegation—Survey of the Treaty—The Turkish Press and the Treaty—Jafar Tayar at Adrianople—Operations of the Government Forces against the Nationalists—French Armistice in Cilicia—Mustafa Kemal’s Operations—Greek Operations in Asia Minor— The Ottoman Delegation’s Observations at the Peace Conference—The Allies’ Answer—Greek Operations in Thrace—The Ottoman Government decides to sign the Treaty—Italo-Greek Incident, and Protests of Armenia, Yugo-Slavia, and King Hussein—Signature of the Treaty – 169—271 VII. THE DISMEMBERMENT OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE: 1. The Turco-Armenian Question - 274—304 2. The Pan-Turanian and Pan-Arabian Movements: Origin of Pan-Turanism—The Turks and the Arabs—The Hejaz—The Emir Feisal—The Question of Syria—French Operations in Syria— Restoration of Greater Lebanon—The Arabian World and the Caliphate—The Part played by Islam - 304—356 VIII. THE MOSLEMS OF THE FORMER RUSSIAN EMPIRE AND TURKEY: The Republic of Northern Caucasus—Georgia and Azerbaïjan—The Bolshevists in the Republics of Caucasus and of the Transcaspian Isthmus—Armenians and Moslems - 357—369 IX. TURKEY AND THE SLAVS: Slavs versus Turks—Constantinople and Russia - 370—408 2 THE TURKS AND EUROPE I THE TURKS The peoples who speak the various Turkish dialects and who bear the generic name of Turcomans, or Turco-Tatars, are distributed over huge territories occupying nearly half of Asia and an important part of Eastern Europe. -

(Self) Fashioning of an Ottoman Christian Prince

Amanda Danielle Giammanco (SELF) FASHIONING OF AN OTTOMAN CHRISTIAN PRINCE: JACHIA IBN MEHMED IN CONFESSIONAL DIPLOMACY OF THE EARLY SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MA Thesis in Comparative History, with a specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. Central European University Budapest CEU eTD Collection May 2015 (SELF) FASHIONING OF AN OTTOMAN CHRISTIAN PRINCE: JACHIA IBN MEHMED IN CONFESSIONAL DIPLOMACY OF THE EARLY SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY by Amanda Danielle Giammanco (United States of America) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with a specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest May 2015 (SELF) FASHIONING OF AN OTTOMAN CHRISTIAN PRINCE: JACHIA IBN MEHMED IN CONFESSIONAL DIPLOMACY OF THE EARLY SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY by Amanda Danielle Giammanco (United States of America) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with a specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards -

Ottoman Holy War to the North of the Danube Full Article Language: En Indien Anders: Engelse Articletitle: 0

_full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien B2 voor dit chapter en nul 0 in hierna): 0 _full_articletitle_deel (kopregel rechts, vul hierna in): Ottoman Holy War to the North of the Danube _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 54 Chapter 3 Chapter 3 Ottoman Holy War to the North of the Danube 1 Efforts to the Way of Allah Initially, as vassals of the Seljukid sultans, the Anatolian beys, including the fledging Ottoman dynasty, accompanied their suzerains in holy campaigns (gaza) against Byzantine territories.1 Adopting the ideology of cihad, the Ot toman sultans assumed for themselves the task of leaders of the holy war against infidels of Southeastern Europe. This idea was directly and most cate gorically declared in “letters of conquest” (fetihnames), accounts of victorious campaigns against unbelievers, distributed both domestically and abroad by the sultans. The most relevant examples of this genre are to be found in Meh med II’s statements in letters sent to Muslim rulers.2 Furthermore, both Byzan tine and Ottoman sources indicate that sultans were conscious of their obligation to conduct cihad. For instance, in 1421, after Mehmed I’s death, as Nişancı Mehmed paşa informs us, his son, Gazi Sultan Murad Han, came to the imperial throne. Murad Han did not abandon but rather followed the right way, hoisted the banners of the holy campaign and the holy war (gaza ü-cihad bayraklarını yücelten) and confided in the glorious Allah.3 Step by step, but especially after the conquest of Arab territories, the image of sultans as leaders of holy wars was recognized across the Muslim world.4 In the sixteenth century, stereotypes dominated the image of the sultan as a holy warrior. -

3038-Tarix-Kultur Ve Qehremanlar

ÖTÜKEN Atsız &o� TARİH, KÜL TÜR ve KAHRAMANLAR (Makaleler-2) YAYIN NU: 864 EDEBİ ESERLER: 368 2. BASIM T.C. KÜLTÜR ve TURİZM BAKANLIGI SERTİFİKA NUMARASI 16267 ISBN 978-975-437-825-2 ÖTÜKEN NEŞRİYAT A.Ş.® İstiklal Cad. Ankara Han 65 /3 • 34433 Beyoğlu-İst anbul Tel: (0212) 25 1 03 50 • (0212) 293 88 71 - Faks: (0212) 251 00 12 Ankara irtibat bürosu: Yüksel Caddesi: 33/5 Kızılay - Ankara Tel: (0312) 431 96 49 İnt er net: www.otuken. com.tr E-po sta: [email protected] Kapak Tasarımı: GNG Tanıtım Dizgi - Tertip: Ötüken Kapak Baskı sı : Pl ato Basım Baskı: Yaylacık Matbaası (0212)6125860 Maltepe mah. Litros yolu Fatih Sanayi Sitesi No: 12/197-203 Topkapı-Zeytinburnu Cilt: Yedigün Mücellithanesi İstanbul-Eylül 2011 İçindekiler Açıklama ................................................................................................. 7 Sunuş ...................................................................................................... 9 TüRK TARiHi HAKKINDA Tarih Şuuru/ Orkun, 20 Nisan 1951 Sayı: 29 ........................................ 13 Telkin ve Pro paganda/ Gözlem , 3 Nisan 1969 ....................................... 22 Edirne Mebusu Şeref Beye Cevap/ Orhun , 20 Şubat 1934, Sayı:4 ........ 26 Türk Or dusunun İftihar Levhası/ Orhun, 1934, Sayı: 6 ........................ 45 Milli Mukaddesat Düşmanları/ Altın Işık , 21 Ocak 1947, Sayı: 2 ......... 55 23 Mayıs (1040) ve 3 Mayıs (1944) /(22/23.4.1975), Ötüken, 1975, S: 5 .................................................................................................. 63 Türk -

Turkish Plastic Arts

Turkish Plastic Arts by Ayla ERSOY REPUBLIC OF TURKEY MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND TOURISM PUBLICATIONS © Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism General Directorate of Libraries and Publications 3162 Handbook Series 3 ISBN: 978-975-17-3372-6 www.kulturturizm.gov.tr e-mail: [email protected] Ersoy, Ayla Turkish plastic arts / Ayla Ersoy.- Second Ed. Ankara: Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 2009. 200 p.: col. ill.; 20 cm.- (Ministry of Culture and Tourism Publications; 3162.Handbook Series of General Directorate of Libraries and Publications: 3) ISBN: 978-975-17-3372-6 I. title. II. Series. 730,09561 Cover Picture Hoca Ali Rıza, İstambol voyage with boat Printed by Fersa Ofset Baskı Tesisleri Tel: 0 312 386 17 00 Fax: 0 312 386 17 04 www.fersaofset.com First Edition Print run: 3000. Printed in Ankara in 2008. Second Edition Print run: 3000. Printed in Ankara in 2009. *Ayla Ersoy is professor at Dogus University, Faculty of Fine Arts and Design. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 Sources of Turkish Plastic Arts 5 Westernization Efforts 10 Sultans’ Interest in Arts in the Westernization Period 14 I ART OF PAINTING 18 The Primitives 18 Painters with Military Background 20 Ottoman Art Milieu in the Beginning of the 20th Century. 31 1914 Generation 37 Galatasaray Exhibitions 42 Şişli Atelier 43 The First Decade of the Republic 44 Independent Painters and Sculptors Association 48 The Group “D” 59 The Newcomers Group 74 The Tens Group 79 Towards Abstract Art 88 Calligraphy-Originated Painters 90 Artists of Geometrical Non-Figurative -

Experiencias De Intervención E Investigación: Buenas Prácticas, Alianzas Y Amenazas I Especialización En Patrimonio Cultural Sumergido Cohorte 2021

Experiencias de intervención e investigación: buenas prácticas, alianzas y amenazas I Especialización en Patrimonio Cultural Sumergido Cohorte 2021 Filipe Castro Bogotá, April 2021 2012-2014 Case Study 1 Gnalić Shipwreck (1569-1583) Jan Brueghel the Elder, 1595 The Gnalić ship was a large cargo ship built in Venice for the merchants Benedetto da Lezze, Piero Basadonna and Lazzaro Mocenigo. Suleiman I (1494-1566) Selim II (1524-1574 Murad III (1546-1595) Mehmed III (1566-1603) It was launched in 1569 and rated at 1,000 botti, a capacity equivalent to around 629 t, which corresponds to a length overall close to 40 m (Bondioli and Nicolardi 2012). Early in 1570, the Gnalić ship transported troops to Cyprus (which fell to the Ottomans in July). War of Cyprus (1570-1573): in spite of losing the Battle of Lepanto (Oct 7 1571), Sultan Selim II won Cyprus, a large ransom, and a part of Dalmatia. In 1571 the Gnalić ship fell into Ottoman hands. Sultan Selim II (1566-1574), son of Suleiman the Magnificent, expanded the Ottoman Empire and won the War of Cyprus (1570-1573). Giovanni Dionigi Galeni was born in Calabria, southern Italy, in 1519. In 1536 he was captured by one of Barbarossa Hayreddin Pasha’s captains and engaged in the galleys as a slave. In 1541 Giovanni Galeni converted to Islam and became a corsair. His skills and leadership capacity eventually made him Bey of Algiers and later Grand Admiral in the Ottoman fleet, with the name Uluç Ali Reis. He died in 1587. In late July 1571 Uluç Ali encountered a large armed merchantman near Corfu: it was the Moceniga, Leze, & Basadonna, captained by Giovanni Tomaso Costanzo (1554-1581), a 16 years old Venetian condottiere (captain of a mercenary army), descendent from a famous 14th century condottiere named Iacomo Spadainfaccia Costanzo, and from Francesco Donato, who was Doge of Venice from 1545 to 1553.