Issues in the Maintenance of Aboriginal Languages and Aboriginal English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sociality and Locality in a Torres Strait Community

Past Visions, Present Lives: sociality and locality in a Torres Strait community. Thesis submitted by Julie Lahn BA (Hons) (JCU) November 2003 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Anthropology, Archaeology and Sociology Faculty of Arts, Education and Social Sciences James Cook University Statement of Access I, the undersigned, the author of this thesis, understand that James Cook University will make it available for use within the University Library and, by microfilm or other means, allow access to users in other approved libraries. All users consulting this thesis will have to sign the following statement: In consulting this thesis I agree not to copy or closely paraphrase it in whole or in part without the written consent of the author; and to make proper public written acknowledgment for any assistance that I have obtained from it. Beyond this, I do not wish to place any restriction on access to this thesis. _________________________________ __________ Signature Date ii Statement of Sources Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text and a list of references is given. ____________________________________ ____________________ Signature Date iii Acknowledgments My main period of fieldwork was conducted over fifteen months at Warraber Island between July 1996 and September 1997. I am grateful to many Warraberans for their assistance and generosity both during my main fieldwork and subsequent visits to the island. -

Aboriginal and Indigenous Languages; a Language Other Than English for All; and Equitable and Widespread Language Services

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 355 819 FL 021 087 AUTHOR Lo Bianco, Joseph TITLE The National Policy on Languages, December 1987-March 1990. Report to the Minister for Employment, Education and Training. INSTITUTION Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education, Canberra. PUB DATE May 90 NOTE 152p. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Advisory Committees; Agency Role; *Educational Policy; English (Second Language); Foreign Countries; *Indigenous Populations; *Language Role; *National Programs; Program Evaluation; Program Implementation; *Public Policy; *Second Languages IDENTIFIERS *Australia ABSTRACT The report proviCes a detailed overview of implementation of the first stage of Australia's National Policy on Languages (NPL), evaluates the effectiveness of NPL programs, presents a case for NPL extension to a second term, and identifies directions and priorities for NPL program activity until the end of 1994-95. It is argued that the NPL is an essential element in the Australian government's commitment to economic growth, social justice, quality of life, and a constructive international role. Four principles frame the policy: English for all residents; support for Aboriginal and indigenous languages; a language other than English for all; and equitable and widespread language services. The report presents background information on development of the NPL, describes component programs, outlines the role of the Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education (AACLAME) in this and other areas of effort, reviews and evaluates NPL programs, and discusses directions and priorities for the future, including recommendations for development in each of the four principle areas. Additional notes on funding and activities of component programs and AACLAME and responses by state and commonwealth agencies with an interest in language policy issues to the report's recommendations are appended. -

1 12Th Oecd-Japan Seminar: “Globalisation And

12TH OECD-JAPAN SEMINAR: “GLOBALISATION AND LINGUISTIC COMPETENCIES: RESPONDING TO DIVERSITY IN LANGUAGE ENVIRONMENTS” COUNTRY NOTE: AUSTRALIA LINGUISTIC CHALLENGES FOR MINORITIES AND MIGRANTS Australia is today a culturally diverse country with people from all over the world speaking hundreds of different languages. Australia has a broad policy of social inclusion, seeking to ensure that all Australians, regardless of their diverse backgrounds are fully included in and able to contribute to society. With its long history of receiving new visitors from overseas, and particularly with the explosion of immigration following World War II, Australia has a great deal of experience in dealing with the linguistic challenges of migrants and minorities. Instead of simply seeking to assimilate new arrivals, Australia seeks to integrate those people into society so that they are able to take full advantage of opportunities, but in a way that respects their cultural traditions and indeed values their diverse experiences. Snapshot of Australian immigration Australia's current Immigration Program allows people from any country to apply to visit or settle in Australia. Decisions are made on a non-discriminatory basis without regard to the applicant's ethnicity, culture, religion or language, provided that they meet the criteria set out in law. In 2005–06, there were 131 600 (ABS, 2006) people who settled permanently in Australia. The top ten countries of origin are: Country of birth % 1 United Kingdom 17.7 2 New Zealand 14.5 3 India 8.6 4 China (excluded SARs and Taiwan) 8.0 5 Philippines 3.7 6 South Africa 3.0 7 Sudan 2.9 8 Malaysia 2.3 9 Singapore 2.0 10 Viet Nam 2.0 Other 35.3 Total 100.0 1 According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2006 census data: Australia's immigrants come from 185 different countries Australians identify with some 250 ancestries and practise a range of religions. -

EALD Information (PDF, 434

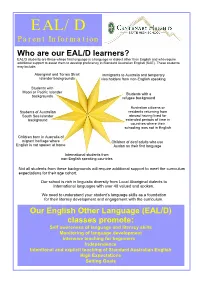

EAL/D Parent Information Who are our EAL/D learners? EAL/D students are those whose first language is a language or dialect other than English and who require additional support to assist them to develop proficiency in Standard Australian English (SAE). These students may include: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Immigrants to Australia and temporary Islander backgrounds visa holders from non-English speaking Students with Maori or Pacific Islander Students with a backgrounds refugee background Australian citizens or Students of Australian residents returning from South Sea islander abroad having lived for background extended periods of time in countries where their schooling was not in English Children born in Australia of migrant heritage where Children of deaf adults who use English is not spoken at home Auslan as their first language International students from non-English speaking countries Not all students from these backgrounds will require additional support to meet the curriculum expectations for their age cohort. Our school is rich in linguistic diversity from Local Aboriginal dialects to International languages with over 40 valued and spoken. We need to understand your student’s language skills as a foundation for their literacy development and engagement with the curriculum. Our English Other Language (EAL/D) classes promote: Self awareness of language and literacy skills Monitoring of language development Intensive teaching for beginners Independence Intentional and explicit teaching of Standard Australian English High Expectations Setting Goals When schools know students speak other languages they can support students in engaging in their learning to reach their educational potential. The information on these questions allows for the right support for your student. -

Re-Awakening Languages: Theory and Practice in the Revitalisation Of

RE-AWAKENING LANGUAGES Theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages Edited by John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch and Michael Walsh Copyright Published 2010 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS University of Sydney Library sydney.edu.au/sup © John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch & Michael Walsh 2010 © Individual contributors 2010 © Sydney University Press 2010 Reproduction and Communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library F03 University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Readers are advised that protocols can exist in Indigenous Australian communities against speaking names and displaying images of the deceased. Please check with local Indigenous Elders before using this publication in their communities. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Re-awakening languages: theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages / edited by John Hobson … [et al.] ISBN: 9781920899554 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Languages--Revival. Australian languages--Social aspects. Language obsolescence--Australia. Language revival--Australia. iv Copyright Language planning--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Hobson, John Robert, 1958- Lowe, Kevin Connolly, 1952- Poetsch, Susan Patricia, 1966- Walsh, Michael James, 1948- Dewey Number: 499.15 Cover image: ‘Wiradjuri Water Symbols 1’, drawing by Lynette Riley. Water symbols represent a foundation requirement for all to be sustainable in their environment. -

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island). -

The Spread of Torres Strait Creole to the Central Islands Of

THE SPREAD OF TORRES STRAIT CREOLE TO THE CENTRAL ISLANDS OF TORRES STRAIT Anna Shnukal INTRODUCTION1 The following paper outlines the second stage of development of Torres Strait Creole, now the lingua franca, or common language, of Torres Strait Islanders everywhere.2 The first stage, which I discussed in an earlier volume of this journal, was that of the creolisation of Pacific Pidgin English around the turn of the century in three Torres Strait island commu nities.3 In that article, I argued that creolisation was the result of two factors not reproduced elsewhere in Torres Strait at the time: (1) the creation of de facto Pacific Islander settle ments on Erub, Ugar and St Paul’s Anglican Mission, Moa, where the Pacific Islanders out numbered Torres Strait Islanders and (2) the integration into those communities of these hitherto marginal immigrants. The prestige of the Pacific Islanders derived from their func tion as linguistic and cultural middlemen, interpreters of European ways of life to their Torres Strait Islander kinfolk. A third stage in the development of the creole began with the war years, when almost all able-bodied men left their home islands to join the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion and, for the first time, came into daily contact with English-speaking Europeans. The present overview article traces the diffusion of Pacific Pidgin English and the creole which developed from it, focusing on the central islands of the Strait between the early 1900s and the beginning of World War II. Also briefly discussed are certain interwoven historical Anna Shnukal carried out research into Torres Strait Creole while a Visiting Research Fellow in Socio linguistics at the Australian Institute o f Aboriginal Studies. -

Print ED356648.TIF

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 356 648 FL 021 143 AUTHOR Lo Bianco, Joseph, Ed. TITLE VOX: The Journal of the Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education (AACLAME). 1989-1991. INSTITUTION Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education, Canberra. REPORT NO ISSN-1032-0458 PUS DATE 91 NOTE 332p.; Intended to be published twice per year. Two-cone charts and colored photographs may not reproduce well. PUS TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT VOX: The Journal of the Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education; n3-5 1989-1991 EDRS PRICE MfO1 /PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Asian Studies; Bilingual Education; Certification; Communicative Competence (Languages); Comparative Education; Diachronic Linguistics; English (Second Language); Ethnic Groups; Foreign Countries; French; Immersion Programs; Immigrants; Indigenous Populations; Interpretive Skills; Italian; *Language Maintenance; *Language Role; Languages for Special Purposes: Language Tests; Language Variation; *Literacy; Minority Groups; Multicultural Education; Native Language Instruction; Pidgins; Second Language Instruction; Second Language Programs; *Second Languages; Sex; Skill Development; Student Attitudes; Testing IDENTIFIERS Africa; *Australia; Japan; Maori (People); Melanesia; Netherlands; New Zealand; Singapore; Spain ABSTRACT This document consists of the three issues of the aerial "VOX" published in 1989-1991. Major articles in these issues include: "The Original Languages of Australia"; "UNESCO and Universal -

Indigenous Australian Languages Fact Sheet

Indigenous Australian Languages Fact Sheet Importance of Indigenous languages and placenames Language is at the core of cultural identity. It links people to their land, it projects history through story and song, it holds the key to kinship systems and to the intricacies of tribal law including spirituality, secret/sacred objects and rites. Language is a major factor in people retaining their cultural identity and many say ‘if the Language is strong, then Culture is strong’. (ATSIC 2000) Language is our soul. (Aunty Rose Fernando, Gamilaroi Elder, 1998) Indigenous 'multiculturalism' and linguistic diversity The population of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities is extremely diverse in its culture with many different languages spoken. Think of the Kimberly region of Western Australia … if you travel through the Kimberly with its large Aboriginal population and the diversity of people within this region, it's just like travelling through Europe with its changing cultures and languages. (Dot West, National Indigenous Media Association of Australia, Boyer Lectures 1993) Even today, it is all too easy to find highly educated and prominent Australians who speak glibly of 'the Aboriginal language', thereby reducing the indigenous linguistic diversity of this country by a factor of at least 100. And it is all too frequently apparent that lurking behind the linguistic naivete of many other mainstream Australians is the suspicion, staggeringly still abroad after over 200 years of white occupation, that Aboriginal languages must be primitive artefacts, small in vocabulary and extremely limited in expressiveness. (Ian Green, University of Tasmania – Riawunna, Center for Aboriginal Education 1999) There are many Indigenous cultures in Australia, made up of people from a rich diversity of tribal groups which each speak their own languages and have a variety of cultural beliefs and traditions. -

Natural and Cultural Histories of the Island of Mabuyag, Torres Strait. Edited by Ian J

Memoirs of the Queensland Museum | Culture Volume 8 Part 1 Goemulgaw Lagal: Natural and Cultural Histories of the Island of Mabuyag, Torres Strait. Edited by Ian J. McNiven and Garrick Hitchcock Minister: Annastacia Palaszczuk MP, Premier and Minister for the Arts CEO: Suzanne Miller, BSc(Hons), PhD, FGS, FMinSoc, FAIMM, FGSA , FRSSA Editor in Chief: J.N.A. Hooper, PhD Editors: Ian J. McNiven PhD and Garrick Hitchcock, BA (Hons) PhD(QLD) FLS FRGS Issue Editors: Geraldine Mate, PhD PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD 2015 © Queensland Museum PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone: +61 (0) 7 3840 7555 Fax: +61 (0) 7 3846 1226 Web: qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 VOLUME 8 IS COMPLETE IN 2 PARTS COVER Image on book cover: People tending to a ground oven (umai) at Nayedh, Bau village, Mabuyag, 1921. Photographed by Frank Hurley (National Library of Australia: pic-vn3314129-v). NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the CEO. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed on the Queensland Museum website qm.qld.gov.au A Queensland Government Project Design and Layout: Tanya Edbrooke, Queensland Museum Printed by Watson, Ferguson & Company ‘Sweet sounds of this place’: contemporary recordings and socio-cultural uses of Mabuyag music Karl NEUENFELDT Neuenfeldt, K. -

Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo

Oceania No. Language [ISO 639-3 Code] Country (Region) 1 ’Are’are [alu] Iouo Solomon Islands 2 ’Auhelawa [kud] Iouo Papua New Guinea 3 Abadi [kbt] Iouo Papua New Guinea 4 Abaga [abg] Iouo Papua New Guinea 5 Abau [aau] Iouo Papua New Guinea 6 Abom [aob] Iouo Papua New Guinea 7 Abu [ado] Iouo Papua New Guinea 8 Adnyamathanha [adt] Iouo Australia 9 Adzera [adz] Iouo Papua New Guinea 10 Aeka [aez] Iouo Papua New Guinea 11 Aekyom [awi] Iouo Papua New Guinea 12 Agarabi [agd] Iouo Papua New Guinea 13 Agi [aif] Iouo Papua New Guinea 14 Agob [kit] Iouo Papua New Guinea 15 Aighon [aix] Iouo Papua New Guinea 16 Aiklep [mwg] Iouo Papua New Guinea 17 Aimele [ail] Iouo Papua New Guinea 18 Ainbai [aic] Iouo Papua New Guinea 19 Aiome [aki] Iouo Papua New Guinea 20 Äiwoo [nfl] Iouo Solomon Islands 21 Ajië [aji] Iouo New Caledonia 22 Ak [akq] Iouo Papua New Guinea 23 Akei [tsr] Iouo Vanuatu 24 Akolet [akt] Iouo Papua New Guinea 25 Akoye [miw] Iouo Papua New Guinea 26 Akukem [spm] Iouo Papua New Guinea 27 Alamblak [amp] Iouo Papua New Guinea 28 Alawa [alh] Iouo Australia 29 Alekano [gah] Iouo Papua New Guinea 30 Alyawarr [aly] Iouo Australia 31 Ama [amm] Iouo Papua New Guinea 32 Amaimon [ali] Iouo Papua New Guinea 33 Amal [aad] Iouo Papua New Guinea 34 Amanab [amn] Iouo Papua New Guinea 35 Amara [aie] Iouo Papua New Guinea 36 Amba [utp] Iouo Solomon Islands 37 Ambae, East [omb] Iouo Vanuatu 38 Ambae, West [nnd] Iouo Vanuatu 39 Ambakich [aew] Iouo Papua New Guinea 40 Amblong [alm] Iouo Vanuatu 1 Oceania No. -

State of Indigenous Languages in Australia 2001 / by Patrick Mcconvell, Nicholas Thieberger

State of Indigenous languages in Australia - 2001 by Patrick McConvell Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Nicholas Thieberger The University of Melbourne November 2001 Australia: State of the Environment Second Technical Paper Series No. 2 (Natural and Cultural Heritage) Environment Australia, part of the Department of the Environment and Heritage © Commonwealth of Australia 2001 This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source and no commercial usage or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those listed above requires the written permission of the Department of the Environment and Heritage. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the State of the Environment Reporting Section, Environment Australia, GPO Box 787, Canberra ACT 2601. The Commonwealth accepts no responsibility for the opinions expressed in this document, or the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this document. The Commonwealth will not be liable for any loss or damage occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this document. Environment Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication McConvell, Patrick State of Indigenous Languages in Australia 2001 / by Patrick McConvell, Nicholas Thieberger. (Australia: State of the Environment Second Technical Paper Series (No.1 Natural and Cultural Heritage)) Bibliography ISBN 064 254 8714 1. Aboriginies, Australia-Languages. 2. Torres Strait Islanders-Languages. 3. Language obsolescence. I. Thieberger, Nicholas. II. Australia. Environment Australia. III. Series 499.15-dc21 For bibliographic purposes, this document may be cited as: McConvell, P.