Cultural Heritage Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural and Cultural Histories of the Island of Mabuyag, Torres Strait. Edited by Ian J

Memoirs of the Queensland Museum | Culture Volume 8 Part 1 Goemulgaw Lagal: Natural and Cultural Histories of the Island of Mabuyag, Torres Strait. Edited by Ian J. McNiven and Garrick Hitchcock Minister: Annastacia Palaszczuk MP, Premier and Minister for the Arts CEO: Suzanne Miller, BSc(Hons), PhD, FGS, FMinSoc, FAIMM, FGSA , FRSSA Editor in Chief: J.N.A. Hooper, PhD Editors: Ian J. McNiven PhD and Garrick Hitchcock, BA (Hons) PhD(QLD) FLS FRGS Issue Editors: Geraldine Mate, PhD PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD 2015 © Queensland Museum PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone: +61 (0) 7 3840 7555 Fax: +61 (0) 7 3846 1226 Web: qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 VOLUME 8 IS COMPLETE IN 2 PARTS COVER Image on book cover: People tending to a ground oven (umai) at Nayedh, Bau village, Mabuyag, 1921. Photographed by Frank Hurley (National Library of Australia: pic-vn3314129-v). NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the CEO. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed on the Queensland Museum website qm.qld.gov.au A Queensland Government Project Design and Layout: Tanya Edbrooke, Queensland Museum Printed by Watson, Ferguson & Company The geology of the Mabuyag Island Group and its part in the geological evolution of Torres Strait Friedrich VON GNIELINSKI von Gnielinski, F. -

Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchOnline at James Cook University Final Report Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward? Allan Dale, Melissa George, Rosemary Hill and Duane Fraser Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward? Allan Dale1, Melissa George2, Rosemary Hill3 and Duane Fraser 1The Cairns Institute, James Cook University, Cairns 2NAILSMA, Darwin 3CSIRO, Cairns Supported by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Programme Project 3.9: Indigenous capacity building and increased participation in management of Queensland sea country © CSIRO, 2016 Creative Commons Attribution Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward? is licensed by CSIRO for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Australia licence. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: 978-1-925088-91-5 This report should be cited as: Dale, A., George, M., Hill, R. and Fraser, D. (2016) Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward?. Report to the National Environmental Science Programme. Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited, Cairns (50pp.). Published by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre on behalf of the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Programme (NESP) Tropical Water Quality (TWQ) Hub. The Tropical Water Quality Hub is part of the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Programme and is administered by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited (RRRC). -

Many Voices Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages Action Plan

Yetimarala Yidinji Yi rawarka lba Yima Yawa n Yir bina ach Wik-Keyangan Wik- Yiron Yam Wik Pa Me'nh W t ga pom inda rnn k Om rungu Wik Adinda Wik Elk Win ala r Wi ay Wa en Wik da ji Y har rrgam Epa Wir an at Wa angkumara Wapabura Wik i W al Ng arra W Iya ulg Y ik nam nh ar nu W a Wa haayorre Thaynakwit Wi uk ke arr thiggi T h Tjung k M ab ay luw eppa und un a h Wa g T N ji To g W ak a lan tta dornd rre ka ul Y kk ibe ta Pi orin s S n i W u a Tar Pit anh Mu Nga tra W u g W riya n Mpalitj lgu Moon dja it ik li in ka Pir ondja djan n N Cre N W al ak nd Mo Mpa un ol ga u g W ga iyan andandanji Margany M litja uk e T th th Ya u an M lgu M ayi-K nh ul ur a a ig yk ka nda ulan M N ru n th dj O ha Ma Kunjen Kutha M ul ya b i a gi it rra haypan nt Kuu ayi gu w u W y i M ba ku-T k Tha -Ku M ay l U a wa d an Ku ayo tu ul g m j a oo M angan rre na ur i O p ad y k u a-Dy K M id y i l N ita m Kuk uu a ji k la W u M a nh Kaantju K ku yi M an U yi k i M i a abi K Y -Th u g r n u in al Y abi a u a n a a a n g w gu Kal K k g n d a u in a Ku owair Jirandali aw u u ka d h N M ai a a Jar K u rt n P i W n r r ngg aw n i M i a i M ca i Ja aw gk M rr j M g h da a a u iy d ia n n Ya r yi n a a m u ga Ja K i L -Y u g a b N ra l Girramay G al a a n P N ri a u ga iaba ithab a m l j it e g Ja iri G al w i a t in M i ay Giy L a M li a r M u j G a a la a P o K d ar Go g m M h n ng e a y it d m n ka m np w a i- u t n u i u u u Y ra a r r r l Y L a o iw m I a a G a a p l u i G ull u r a d e a a tch b K d i g b M g w u b a M N n rr y B thim Ayabadhu i l il M M u i a a -

Your Labor Member in the Queensland Parliament

YOUR LABOR MEMBER IN THE QUEENSLAND PARLIAMENT Cape Vork / Douglas / Cooktown / Mareeba: Torres Strait / NPA P: 1800816264 - Fax: 07 40312437 P: 1800802391 - Fax: 07 4069 1620 PO Box 2080, Cairns 4870 PO Box 437, Thursday Island 4875 E: [email protected] E: cook.th [email protected] Submission to the Queensland Competition Authority Level 19 12 Creek Street BRISBANE QLD 4001 REVIEW OF SUN WATER PRICING STRUCTURE Submission to the Queensland Competition Authority by Jason O'Brien MP Member for Cook, on behalf of a constituent who is a Sun Water user, requesting changes to the pricing policy of Sun Water to their customers holding pension concession cards who access sun water for their domestic use only. Under the present Sun Water tariff structure they are able to negotiate how much revenue could be collected from variable and fixed charges. My submission is that Sun Water should be free to offer a Pensioner Water Subsidy Scheme for eligible pensions to reduce the impact of increased water price increases. This concession could be in the form of a rebate similar to the rate rebate scheme which applies across the state off local government rates charges. Sun Water must have the ability to provide water services to the community at a reasonable cost taking into account the most effective way to utilise the resource for the community's benefit. To this end pensions accessing Sun Water's resource purely for domestic use should be considered in a wider public interest context. Prices should be cost reflective and take into account relevant public interest matters such as pensioners accessing their resource In conclusion I submit that Sun Water should be providing a Pensioner Water Subsidy Scheme and the Queensland Competition Authority should recognise this as a public interest issue. -

LAADE W01 Sound Recordings Collected by Wolfgang Laade, 1963

Interim Finding aid LAADE_W01 Sound recordings collected by Wolfgang Laade, 1963-1965 Prepared February 2013 by MH Last updated 23 December 2016 ACCESS Availability of copies Listening copies are available. Contact the AIATSIS Audiovisual Access Unit by completing an online enquiry form or phone (02) 6261 4212 to arrange an appointment to listen to the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on listening Some materials in this collection are restricted and may only be listened to by clients who have obtained permission from AIATSIS as well as the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community. For more details, contact Access and Client Services by sending an email to [email protected] or phone (02) 6261 4212. Restrictions on use This collection is partially restricted. It contains some materials which may only be copied by clients who have obtained permission from AIATSIS as well as the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community. For more details, contact Access and Client Services by sending an email to [email protected] or phone (02) 6261 4212. Permission must be sought from AIATSIS as well as the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community for any publication or quotation of this material. Any publication or quotation must be consistent with the Copyright Act (1968). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1963-1965 Extent: 82 sound tape reels (ca. 34 hrs. 30 min.) : analogue, 3 3/4 ips, 2 track, mono. ; 7 in. (not held). Production history These recordings were collected by Dr Wolfgang Laade of the Freie Universität, West Berlin, between 1963 and 1965 at various locations on Cape York Peninsula and the Torres Strait Islands, Queensland, Australia. -

Guidelines for Preparing and Assessing Connection Material for Native Title Claims in Queensland

Guidelines for preparing and assessing connection material for Native Title Claims in Queensland November 2016 This publication has been compiled by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land Services, Department of Natural Resources and Mines. © State of Queensland, 2016 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. The Queensland Government shall not be liable for technical or other errors or omissions contained herein. The reader/user accepts all risks and responsibility for losses, damages, costs and other consequences resulting directly or indirectly from using this information. Table of contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 2 The connection material to be provided to the State ............................................................... 4 3 The contents -

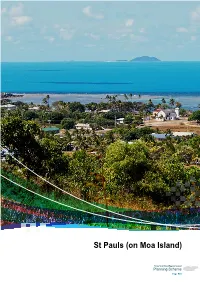

St Pauls (On Moa Island) - Local Plan Code

7.2.13 St Pauls (on Moa Island) - local plan code Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) St Pauls (on Moa Island) Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 523 Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 524 Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) Papua New Guinea Saibai Ugar Boigu Stephen Island Erub Dauan Darnley Island Masig Yorke Island Iama Mabuyag Yam Island Mer Poruma Murray Island Coconut Island Badu Kubin Moa SStt PPaulsauls Warraber Sue Island Keriri Hammond Island Mainland Australia Mainland Australia Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 525 Editor’s Note – Community Snapshot Location Topography and Environment • St Pauls is located on the eastern side of Moa • Moa Island, like other islands in the group, is Island, which is part of the Torres Strait inner and a submerged remnant of the Great Dividing near western group of islands. St Paul’s nearest Range, now separated by sea. The island neighbour is Kubin, which is located on the comprises of largely of rugged, open forest and south-western side of Moa Island. Approximately is approximately 17km in diameter at its widest 15km from the outskirts of St Pauls. point. • Native flora and fauna that have been identified Population near St Pauls include fawn leaf nosed bat, • According to the most recent census, there were grey goshawk, emerald monitor, little tern, 258 people living in St Pauls as at August 2011, red goshawk, radjah shelduck, lipidodactylus however, the population is highly transient and primilus, bare backed fruit bat, torresian tube- this may not be an accurate estimate. -

Part 16 Transport Infrastructure Plan

Figure 7.3 Option D – Rail Line from Cairns to Bamaga Torres Strait Transport Infrastructure Plan Masig (Yorke) Island Option D - Rail Line from Cairns to Bamaga Major Roads Moa Island Proposed Railway St Pauls Kubin Waiben (Thursday) Island ° 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 Kilometres Seisia Bamaga Ferry and passenger services as per current arrangements. DaymanPoint Shelburne Mapoon Wenlock Weipa Archer River Coen Yarraden Dixie Cooktown Maramie Cairns Normanton File: J:\mmpl\10303705\Engineering\Mapping\ArcGIS\Workspaces\Option D - Rail Line.mxd 29.07.05 Source of Base Map: MapData Sciences Pty Ltd Source for Base Map: MapData Sciences Pty Ltd 7.5 Option E – Option A with Additional Improvements This option retains the existing services currently operating in the Torres Strait (as per Option A), however it includes additional improvements to the connections between Horn Island and Thursday Island. Two options have been strategically considered for this connection: Torres Strait Transport Infrastructure Plan - Integrated Strategy Report J:\mmpl\10303705\Engineering\Reports\Transport Infrastructure Plan\Transport Infrastructure Plan - Rev I.doc Revision I November 2006 Page 91 • Improved ferry connections; and • Roll-on roll-of ferry. Improved ferry connections This improvement considers the combined freight and passenger services between Cairns, Bamaga and Thursday Island, with a connecting ferry service to OSTI communities. Possible improvements could include co-ordinating fares, ticketing and information services, and also improving safety, frequency and the cost of services. Roll-on roll-off ferry A roll-on roll-off operation between Thursday Island and Horn Island would provide significant benefits in moving people, cargo, and vehicles between the islands. -

Navigating Boundaries: the Asian Diaspora in Torres Strait

CHAPTER TWO Tidal Flows An overview of Torres Strait Islander-Asian contact Anna Shnukal and Guy Ramsay Torres Strait Islanders The Torres Strait Islanders, Australia’s second Indigenous minority, come from the islands of the sea passage between Queensland and New Guinea. Estimated to number at most 4,000 people before contact, but reduced by half by disease and depredation by the late-1870s, they now number more than 40,000. Traditional stories recount their arrival in waves of chain migration from various islands and coastal villages of southern New Guinea, possibly as a consequence of environmental change.1 The Islanders were not traditionally unified, but recognised five major ethno-linguistic groups or ‘nations’, each specialising in the activities best suited to its environment: the Miriam Le of the fertile, volcanic islands of the east; the Kulkalgal of the sandy coral cays of the centre; the Saibailgal of the low mud-flat islands close to the New Guinea coast; the Maluilgal of the grassy, hilly islands of the centre west; and the Kaurareg of the low west, who for centuries had intermarried with Cape York Aboriginal people. They spoke dialects of two traditional but unrelated languages: in the east, Papuan Meriam Mir; in the west and centre, Australian Kala Lagaw Ya (formerly called Mabuiag); and they used a sophisticated sign language to communicate with other language speakers. Outliers of a broad Melanesian culture area, they lived in small-scale, acephalous, clan-based communities and traded, waged war and intermarried with their neighbours and the peoples of the adjacent northern and southern mainlands. -

A Historical and Legal Study of Sovereignty in the Canadian North : Terrestrial Sovereignty, 1870–1939

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939 Smith, Gordon W. University of Calgary Press "A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939", Gordon W. Smith; edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50251 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca A HISTORICAL AND LEGAL STUDY OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE CANADIAN NORTH: TERRESTRIAL SOVEREIGNTY, 1870–1939 By Gordon W. Smith, Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer ISBN 978-1-55238-774-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at ucpress@ ucalgary.ca Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

The Anglicans in New Guinea and the Torres Strait Islands

wether1 Page 1 Monday, June 26, 2000 11:52 AM PACIFIC STUDIES Vol. 21, No. 4 December 1998 THE ANGLICANS IN NEW GUINEA AND THE TORRES STRAIT ISLANDS David Wetherell Deakin University This study compares the Anglican diocese of Carpentaria in northeastern Aus- tralia with its Anglican neighbor the diocese of New Guinea. While New Guinea called for sacrifice on a heroic scale as befitted a mission among pure “pagans,” Carpentaria was intended primarily as a church for Europeans. However, the withdrawal of thousands of settlers from the Gulf of Carpentaria country from 1910 to 1942 in the wake of recurrent cyclones, economic depression, and drought led to wholesale white depopulation. This depopulation, added to the Anglicans’ acceptance of the London Missionary Society’s sphere in the Torres Strait Islands, left Carpentaria overwhelmingly Islander and Aboriginal in char- acter. Papua New Guinea headed for independence in state and church from the 1960s, but Carpentaria remained largely a missionary diocese, part of whose populations it managed for half a century on threadbare mission stations, with the empty-handed encouragement of the Queensland government. “Those damned churchmen are like the Papists,” remarked M. H. More- ton to a fellow British New Guinea magistrate, “plenty of them willing to be martyrs.”1 The New Guinea Anglican Mission, established by Albert Maclaren and Copland King in 1891, was regarded by its supporters during its “golden age” from the postwar period to 1960 as one of the glories of the Anglican Communion. Its bishop, Philip Strong, was accorded an honored place at Lambeth conferences; its workers, seemingly unbowed by physical deprivation, were acclaimed for upholding the highest ideals of self-sacrifice. -

Week16 E-Record .Indd

PINEAPPLE HOTEL CUP E-FOOTY RECORD ROUND 16 E-Footy RECORD 2nd August 2008 Issue 16 Editorial with Marty King GET INTO THE SPIRIT OF KICK AROUND AUSTRALIA DAY Next Thursday, 7th August, is the 150th anniversary of the fi rst recorded match of Australian Football between Melbourne schools Scotch College and Melbourne Grammar at Richmond Paddock, at what is now Yarra Park next to the MCG. As part of the celebrations of this wonderful occasion the AFL is staging ‘Kick Around Australia Day’ and I hope footy fans throughout Queensland will join the party. It’s an opportunity for all Australians to come together through football, and to wear your team colours or club scarf and have a kick of the famous Sherrin. There will be a stack of celebrations right across the country, but please, wherever you are and whatever you are doing, be part of it. Introduce friends, workmates and school friends to AFL and all that makes it the No.1 sport in Australia. Schools around the country have been busy making preparations for the day, with thousands of kids set to take part in football themed lessons, designed in line with the curriculum. Businesses and community organizations, too, are encouraged to get into the spirit and help recognize football’s 150th birthday, which is part of the Tom Wills Round, dedicated to one of the founding forefathers of our game. For further information on this and other 150th year celebrations, visit www.150years.com.au AND CONGRATULATIONS TO THE QUEENSLAND COUNTRY SIDE Special congratulations to the Queensland Country side which won the division two title at last week’s Australian Country Championships in Shepparton, Victoria.