Publisher Version (Open Access)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crusader Kings II to Europa Universalis IV Converter Summary

Crusader Kings II to Europa Universalis IV Converter The Crusader Kings II to Europa Universalis IV Converter will let you take any point in time in the Crusader Kings II game and convert that into a Europa Universalis IV game. You can export your Crusader Kings II game at any time while playing or when at the end game screen. In the Europa Universalis IV launcher, you then select the exported game as a mod. No matter what the game date is in Crusader Kings II, it will be 1444 in Europa Universalis IV. Crusader Kings II features a lot of content with focus on Europe, which gives us more nations, different religions, culture groups and so on than exist in Europa Universalis IV. So, let's say you managed to save Zoroastrianism from extinction in your game. Even though EU4 does not have that religion, the converter will create a mod for Europa Universalis IV where it does! Among the dynamically created things are nation names, cultures, religions and flags. We've tried to transfer as much data as possible from Crusader Kings II, including special events. Independent Counts and Dukes of Crusader Kings II will be happy to know that they'll get promoted to kings after converting. Buildings, wars and technology are not exported since there is no way to map them to something in Europa Universalis IV in any sensible way. Every independent nation is converted to a Europa Universalis IV equivalent where possible. Where it is impossible to map it to an already existing one a new nation is created with its own unique flag. -

Crusader Kings 2 2.8.2.1 Download Free Crusader Kings II - Middle Mars V.1.0.6 - Game Mod - Download

crusader kings 2 2.8.2.1 download free Crusader Kings II - Middle Mars v.1.0.6 - Game mod - Download. The file Middle Mars v.1.0.6 is a modification for Crusader Kings II , a(n) strategy game. Download for free. file type Game mod. file size 58.1 MB. last update Tuesday, April 6, 2021. Report problems with download to [email protected] Middle Mars is a mod for Crusader Kings II , created by zombaxx. Description: Long ago, many centuries after Mars had been fully Terraformed, Earth went dark on the same day all existing electronics on Mars stopped working. All ships not in orbit fell from the sky. Mars quickly descended into chaos as society collapsed, bringing on a new Dark Age. Most of the population succumbed to famine as governments broke down and nations fractured. Around 1000 years later humanity is recovering and has entered a new Medieval Era, largely forgetting the accurate history of humanity and the disaster. No one knows if Earth is still around and is thought of as more of a holy icon and legend. Some ideologies reject the concept or existence of Earth as we know it. Extract into �My Documents\Paradox Interactive\Crusader Kings II\mods� and activate in game�s menu. Crusader Kings II - Zhiza v.6022021 - Game mod - Download. The file Zhiza v.6022021 is a modification for Crusader Kings II , a(n) strategy game. Download for free. file type Game mod. file size 1.3 MB. last update Wednesday, March 10, 2021. Report problems with download to [email protected] Zhiza is a mod for Crusader Kings II , created by modester. -

Many Voices Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages Action Plan

Yetimarala Yidinji Yi rawarka lba Yima Yawa n Yir bina ach Wik-Keyangan Wik- Yiron Yam Wik Pa Me'nh W t ga pom inda rnn k Om rungu Wik Adinda Wik Elk Win ala r Wi ay Wa en Wik da ji Y har rrgam Epa Wir an at Wa angkumara Wapabura Wik i W al Ng arra W Iya ulg Y ik nam nh ar nu W a Wa haayorre Thaynakwit Wi uk ke arr thiggi T h Tjung k M ab ay luw eppa und un a h Wa g T N ji To g W ak a lan tta dornd rre ka ul Y kk ibe ta Pi orin s S n i W u a Tar Pit anh Mu Nga tra W u g W riya n Mpalitj lgu Moon dja it ik li in ka Pir ondja djan n N Cre N W al ak nd Mo Mpa un ol ga u g W ga iyan andandanji Margany M litja uk e T th th Ya u an M lgu M ayi-K nh ul ur a a ig yk ka nda ulan M N ru n th dj O ha Ma Kunjen Kutha M ul ya b i a gi it rra haypan nt Kuu ayi gu w u W y i M ba ku-T k Tha -Ku M ay l U a wa d an Ku ayo tu ul g m j a oo M angan rre na ur i O p ad y k u a-Dy K M id y i l N ita m Kuk uu a ji k la W u M a nh Kaantju K ku yi M an U yi k i M i a abi K Y -Th u g r n u in al Y abi a u a n a a a n g w gu Kal K k g n d a u in a Ku owair Jirandali aw u u ka d h N M ai a a Jar K u rt n P i W n r r ngg aw n i M i a i M ca i Ja aw gk M rr j M g h da a a u iy d ia n n Ya r yi n a a m u ga Ja K i L -Y u g a b N ra l Girramay G al a a n P N ri a u ga iaba ithab a m l j it e g Ja iri G al w i a t in M i ay Giy L a M li a r M u j G a a la a P o K d ar Go g m M h n ng e a y it d m n ka m np w a i- u t n u i u u u Y ra a r r r l Y L a o iw m I a a G a a p l u i G ull u r a d e a a tch b K d i g b M g w u b a M N n rr y B thim Ayabadhu i l il M M u i a a -

Master's Thesis: Visualizing Storytelling in Games

Chronicle Developing a visualisation of emergent narratives in grand strategy games EDVARD RUTSTRO¨ M JONAS WICKERSTRO¨ M Master's Thesis in Interaction Design Department of Applied Information Technology Chalmers University of Technology Gothenburg, Sweden 2013 Master's Thesis 2013:091 The Authors grants to Chalmers University of Technology and University of Gothen- burg the non-exclusive right to publish the Work electronically and in a non-commercial purpose make it accessible on the Internet. The Authors warrants that they are the authors to the Work, and warrants that the Work does not contain text, pictures or other material that violates copyright law. The Authors shall, when transferring the rights of the Work to a third party (for example a publisher or a company), acknowledge the third party about this agreement. If the Authors has signed a copyright agreement with a third party regarding the Work, the Authors warrants hereby that they have obtained any necessary permission from this third party to let Chalmers University of Technology and University of Gothenburg store the Work electronically and make it accessible on the Internet. Chronicle Developing a Visualisation of Emergent Narratives in Grand Strategy Games c EDVARD RUTSTROM,¨ June 2013. c JONAS WICKERSTROM,¨ June 2013. Examiner: OLOF TORGERSSON Department of Applied Information Technology Chalmers University of Technology, SE-412 96, G¨oteborg, Sweden Telephone +46 (0)31-772 1000 Gothenburg, Sweden June 2013 Abstract Many games of high complexity give rise to emergent narratives, where the events of the game are retold as a story. The goal of this thesis was to investigate ways to support the player in discovering their own emergent stories in grand strategy games. -

LAADE W01 Sound Recordings Collected by Wolfgang Laade, 1963

Interim Finding aid LAADE_W01 Sound recordings collected by Wolfgang Laade, 1963-1965 Prepared February 2013 by MH Last updated 23 December 2016 ACCESS Availability of copies Listening copies are available. Contact the AIATSIS Audiovisual Access Unit by completing an online enquiry form or phone (02) 6261 4212 to arrange an appointment to listen to the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on listening Some materials in this collection are restricted and may only be listened to by clients who have obtained permission from AIATSIS as well as the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community. For more details, contact Access and Client Services by sending an email to [email protected] or phone (02) 6261 4212. Restrictions on use This collection is partially restricted. It contains some materials which may only be copied by clients who have obtained permission from AIATSIS as well as the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community. For more details, contact Access and Client Services by sending an email to [email protected] or phone (02) 6261 4212. Permission must be sought from AIATSIS as well as the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community for any publication or quotation of this material. Any publication or quotation must be consistent with the Copyright Act (1968). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1963-1965 Extent: 82 sound tape reels (ca. 34 hrs. 30 min.) : analogue, 3 3/4 ips, 2 track, mono. ; 7 in. (not held). Production history These recordings were collected by Dr Wolfgang Laade of the Freie Universität, West Berlin, between 1963 and 1965 at various locations on Cape York Peninsula and the Torres Strait Islands, Queensland, Australia. -

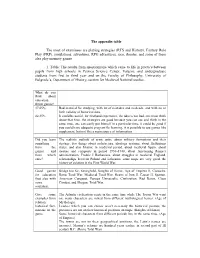

The Appendix Table the Most of Examinees Are Playing Strategies

The appendix table The most of examinees are playing strategies (RTS and History), Fantasy Role Play (FRP), simulations, adventures, RPG adventures, race, shooter, and some of them also play memory games. 1. Table: The results from questionnaire which came to life in practice between pupils from high schools in Petnica Science Center, Valjevo, and undergraduate students from first to third year and on the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Belgrade’s, Department of History, section for Medieval National studies. What do you think about education throw games? 17,65% Bad material for studying, with lot of mistakes and misleads; and with no or little validity of historical data. 82,35% It could be useful, for firsthand experience, the idea is not bad, one must think about that time, the strategies are good because you can see and think in the same time, one can easily put himself in a particular time, it could be good if you could have adequate program for learning, it is possible to use games like supplement, but not like a main source of information. Did you learn The realistic outlook of army units, about military formations and their something strategy, few things about architecture, ideology systems, about Hellenisms from the states, and also Islamic in medieval period, about medieval Spain, about games and treaties and conquests in period 1936–1948, about functioning Rome’s from which administration, Fredric I Barbarossa, about struggles in medieval England, ones? relationships between Poland and Lithuania, some maps are very good, the history of aviation in the First World War. -

Chinese Corporate Acquisitions in Sweden: a Survey Jerker Hellström, Oscar Almén, Johan Englund

Chinese corporate acquisitions in Sweden: A survey Jerker Hellström, Oscar Almén, Johan Englund Main conclusions • This survey has resulted in the first comprehensive and openly accessible compilation of Chinese corporate acquisitions in Sweden. • The audit has identified 51 companies in Sweden in which Chinese (including Hong Kong) companies have acquired a majority ownership. In addition, the survey has identified another 14 minority acquisitions. • Zhejiang Geely’s acquisition of a minority stake in Swedish truck-maker AB Volvo was among the largest Chinese acquisitions completed in Europe and North America in 2018. • Through these acquisitions, Chinese investors have taken control of at least some one hundred subsidiaries. • Most of the identified acquisitions were made since 2014. The highest annual amount of acquisitions was recorded in 2017. • The majority of the acquired companies belong to the following five sectors: industrial products and machinery, health and biotechnology, information and communications technology (ICT), electronics, and the automotive industry. • For nearly half of the acquired companies, there is a correlation between their operations and the technology sectors highlighted in the “Made in China 2025” plan for China's national industrial development. The sectors included in the plan are of particular importance to the Chinese state. • This survey includes several companies that have not been identified as Chinese acquisitions in previous compilations of Chinese investments. • More than 1,000 companies have reported to Sweden’s Companies Registration Office that their beneficial owner is a citizen of either China or Hong Kong. For the majority of these companies, however, the Chinese ownership is not a result of an acquisition. -

Year-End Report and Quarterly Report October - December 2020-01-01 - 2020-12-31

YEAR-END REPORT AND QUARTERLY REPORT OCTOBER - DECEMBER 2020-01-01 - 2020-12-31 YEAR-END REPORT AND QUARTERLY REPORT OCTOBER - DECEMBER 2020-01-01 - 2020-12-31 *Please note that this is a translation for information purposes only - in case of any discrepancies between this version and the Swedish, the Swedish version shall prevail. Paradox Interactive AB (publ) • Org.nr: 556667-4759 • Magnus Ladulåsgatan 4, 118 66 Stockholm • www.paradoxinteractive.com 1 YEAR-END REPORT AND QUARTERLY REPORT OCTOBER - DECEMBER 2020-01-01 - 2020-12-31 YEAR-END REPORT AND QUARTERLY REPORT OCTOBER - DECEMBER 2020-01-01 - 2020-12-31 FOURTH QUARTER 2020 IMPORTANT EVENTS IN THE FOURTH QUARTER 2020 • Revenues amounted to MSEK 433.7 (MSEK 381.3), an increase by 14 % • The new game Empire of Sin, developed by Romero Games, was released compared to the same period last year. December 1, 2020. • Operating profit amounted to MSEK 79.5 (MSEK 163.5), a decrease by 51 %. • Two expansions were released during the period; Star Kings for Age of • Profit after financial items amounted to MSEK 78.6 (MSEK 156.7), and profit Wonders: Planetfall, and Battle for the Bosporus for Hearts of Iron IV. after tax amounted to MSEK 59.5 (MSEK 130.5). • The Group’s employees continue to work from home to reduce the spread of • Cash flow from operating activities amounted to MSEK 387.1 (MSEK 265.4), and Covid-19. cash flow from investing activities amounted to MSEK -207.3 (MSEK -135.4). • By the end of the period cash amounted to MSEK 767.6 (MSEK 554.2). -

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island). -

Cape York Region

141°0'E 142°0'E 143°0'E 144°0'E 145°0'E Buru Erubam Le & Warul Ugar (Stephens (Darnley Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on boundaries with areas excluded or discrete boundaries of areas being claimed) as To determine whether any areas fall within the external boundary of an application or Kawa data sourced from Department of Natural Resources, MIsinlaens daendrs E) n#e1rgy (Qld) © ITshlaendtehresy) h#a1ve been recognised by the Federal Court process. determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and State of Queensland for that portion where their data has been used. Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 Topographic vector data is © CommonwealthM aosf iAgu Psteraolipal e(Geoscience Australia) Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. © Commonwealth of Australia 2019 Gebara 2006. and Damuth The applications shown on the map include: Non freehold land tenure sourced from DNRME (QLD) February 2019. - registered applications (i.e. those that have complied with the registration test), The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents Cape York Region Islanders #1 People - new and/or amended applications where the registration test is being applied, and the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give As part oYf atmhe transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in 1998, all - unregistered applications (i.e. -

Interim Report 2019-01-01 - 2019-06-30

INTERIM REPORT 2019-01-01 - 2019-06-30 INTERIM REPORT 2019-01-01 - 2019-06-30 *Please note that this is a translation for information purposes only - in case of any discrepancies between this version and the Swedish, the Swedish version shall prevail. Paradox Interactive AB (publ) • Org.nr: 556667-4759 • Västgötagatan 5, 6th floor • S -118 27 Stockholm • www.paradoxinteractive.com 1 INTERIM REPORT 2019-01-01 - 2019-06-30 INTERIM REPORT 2019-01-01 - 2019-06-30 SECOND QUARTER 2019 • In June, the new game Empire of Sin was announced, developed by Romero • Revenues amounted to SEK 387.2 (298.8) million, an increase by 30 % compa- Games. The game is planned for release in spring 2020. red to the same period last year. • A collaboration has been initiated with publisher and developer Double • Operating profit amounted to SEK 154.2 (99.4) million, an increase by 55 %. Eleven for continued development of the game Prison Architect on PC and • Profit before tax amounted to SEK 154.0 (99.5) million, and profit after tax console. amounted to SEK 120.3 (77.9) million. • Steam Summer Sale took place June 25 to July 9. • Cash flow from operating activities amounted to SEK 232.7 (182.3) million, • At the Annual General Meeting on May 17, Mathias Hermansson was elected and cash flow from investing activities amounted to SEK -104.9 (-121.2) million. as a new board member. Cecilia Beck-Friis declined re-election. • By the end of the period cash amounted to SEK 396.4 (329.3) million. -

Europa Universalis Iv As a Catalyst for Worldbuilding

WORLDBUILDING INSIDE A BOX: EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV AS A CATALYST FOR WORLDBUILDING JAYHANT SAULOG School of Design and Informatics Abertay University (May 2018) ABSTRACT Worldbuilding (the practice of creating fictional worlds) faces a unique challenge due to video games’ interactive nature, especially regarding sandbox games and non-linear narratives: how does one build a world in a genre so inherently pervasive? Where the player can be anyone and travel anywhere at any time? Where the game is less driven by the main story (or even lacking it completely), and instead leaves the world and setting to stand on its own? However, with the right platform, the pervasive nature of the sandbox genre can act as a catalyst to work to the worldbuilder’s advantage. When the platform asks questions, the worldbuilder is called to answer, and from this a development loop occurs resulting in a fleshed-out world that truly works in cooperation with the game. The research will seek to uncover the effectiveness of using the sandbox-strategy game Europa Universalis IV as a catalyst in the creation of a fantasy setting. The practical-led research will be twofold: the development of a game mod and the development of the world it will be set in. In addition to the main case study above, the research will look at existing literature on worldbuilding as well as a comparative approach on how other successful games have worldbuilt their settings. Keywords: worldbuilding, narrative, strategy, exposition, sandbox, secondary belief PREFACE I first started worldbuilding back in 2014 for the game Europa Universalis IV, set around an event called the Blackpowder Rebellion: an 18th century fantasy setting in which the commonfolk led a revolution against their magical masters with the help of gunpowder weapons.