The History of Educational Computer Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Video Game Consoles Introduction the First Generation

A History of Video Game Consoles By Terry Amick – Gerald Long – James Schell – Gregory Shehan Introduction Today video games are a multibillion dollar industry. They are in practically all American households. They are a major driving force in electronic innovation and development. Though, you would hardly guess this from their modest beginning. The first video games were played on mainframe computers in the 1950s through the 1960s (Winter, n.d.). Arcade games would be the first glimpse for the general public of video games. Magnavox would produce the first home video game console featuring the popular arcade game Pong for the 1972 Christmas Season, released as Tele-Games Pong (Ellis, n.d.). The First Generation Magnavox Odyssey Rushed into production the original game did not even have a microprocessor. Games were selected by using toggle switches. At first sales were poor because people mistakenly believed you needed a Magnavox TV to play the game (GameSpy, n.d., para. 11). By 1975 annual sales had reached 300,000 units (Gamester81, 2012). Other manufacturers copied Pong and began producing their own game consoles, which promptly got them sued for copyright infringement (Barton, & Loguidice, n.d.). The Second Generation Atari 2600 Atari released the 2600 in 1977. Although not the first, the Atari 2600 popularized the use of a microprocessor and game cartridges in video game consoles. The original device had an 8-bit 1.19MHz 6507 microprocessor (“The Atari”, n.d.), two joy sticks, a paddle controller, and two game cartridges. Combat and Pac Man were included with the console. In 2007 the Atari 2600 was inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame (“National Toy”, n.d.). -

Simcity 2000 Manual

™ THE ULTIMATE CITY SIMULATOR USER’S MANUAL Title Pages 3/25/98 12:00 PM Page 1 ª THE ULTIMATE CITY SIMULATOR USER MANUAL by Michael Bremer On the whole I’d rather be in Philadelphia. – W.C. Fields (1879-1946) Credits The Program Designed By: Fred Haslam and Will Wright IBM Programming: Jon Ross, Daniel Browning, James Turner Windows Programming: James Turner, Jon Ross Producer: Don Walters Art Director: Jenny Martin Computer Art: Suzie Greene (Lead Artist), Bonnie Borucki, Kelli Pearson, Eben Sorkin Music: Sue Kasper, Brian Conrad, Justin McCormick Sound Driver: Halestorm, Inc. Sound Effects: Maxis Sample Heds, Halestorm, Inc. Technical Director: Brian Conrad Newspaper Articles: Debra Larson, Chris Weiss Special Technical Assistance: Bruce Joffe (GIS Consultant), Craig Christenson (National Renewable Energy Laboratory), Ray Gatchalian (Oakland Fire Department), Diane L. Zahm (Florida Department of Law Enforcement) The Manual Written By: Michael Bremer Copy Editors: Debra Larson, Tom Bentley Documentation Design: Vera Jaye, Kristine Brogno Documentation Layout: David Caggiano Contributions To Documentation: Fred Haslam, Will Wright, Don Walters, Kathleen Robinson Special Artistic Contributions: John “Bean” Hastings, Richard E. Bartlett, AIA, Margo Lockwood, Larry Wilson, David Caggiano, Tom Bentley, Barbara Pollak, Emily Friedman, Keith Ferrell, James Hewes, Joey Holliday, William Holliday The Package Package Design: Jamie Davison Design, Inc. Package Illustration: David Schleinkofer The Maxis Support Team Lead Testers: Chris Weiss, Alan -

Digital Games As a Context for Children's Cognitive Development

Volume 32, Number 1 | 2019 Social Policy Report Digital Games as a Context for Children’s Cognitive Development: Research Recommendations and Policy Considerations Fran C. Blumberg, Fordham University Kirby Deater-Deckard, University of Massachusetts-Amherst Sandra L. Calvert, Georgetown University Rachel M. Flynn, Northwestern University C. Shawn Green, University of Wisconsin-Madison David Arnold, University of Massachusetts-Amherst Patricia J. Brooks, College of Staten Island & The Graduate Center, CUNY ABSTRACT We document the need to examine digital game play and app use as a context for cognitive development, particularly during middle childhood. We highlight this developmental period as 6- through 12- year olds comprise a large swath of the preadult population that plays and uses these media forms. Surprisingly, this age range remains understudied with regard to the impact of their interactive media use as compared to young children and adolescents. This gap in knowledge about middle childhood may refect strong and widely held concerns about the effects of digital games and apps before and after this period. These concerns include concurrent and subsequent infuences of game use on very young children’s and adolescents’ cognitive and socioemotional functioning. We highlight here what is currently known about the impact of media on young children and adolescents and what is not known about this impact in middle childhood. We then offer recommendations for the types of research that developmental scientists can undertake to examine the effcacy of digital games within the rapidly changing media ecology in which children live. We conclude with a discussion of media policies that we believe can help children beneft from their media use. -

Master's Thesis: Visualizing Storytelling in Games

Chronicle Developing a visualisation of emergent narratives in grand strategy games EDVARD RUTSTRO¨ M JONAS WICKERSTRO¨ M Master's Thesis in Interaction Design Department of Applied Information Technology Chalmers University of Technology Gothenburg, Sweden 2013 Master's Thesis 2013:091 The Authors grants to Chalmers University of Technology and University of Gothen- burg the non-exclusive right to publish the Work electronically and in a non-commercial purpose make it accessible on the Internet. The Authors warrants that they are the authors to the Work, and warrants that the Work does not contain text, pictures or other material that violates copyright law. The Authors shall, when transferring the rights of the Work to a third party (for example a publisher or a company), acknowledge the third party about this agreement. If the Authors has signed a copyright agreement with a third party regarding the Work, the Authors warrants hereby that they have obtained any necessary permission from this third party to let Chalmers University of Technology and University of Gothenburg store the Work electronically and make it accessible on the Internet. Chronicle Developing a Visualisation of Emergent Narratives in Grand Strategy Games c EDVARD RUTSTROM,¨ June 2013. c JONAS WICKERSTROM,¨ June 2013. Examiner: OLOF TORGERSSON Department of Applied Information Technology Chalmers University of Technology, SE-412 96, G¨oteborg, Sweden Telephone +46 (0)31-772 1000 Gothenburg, Sweden June 2013 Abstract Many games of high complexity give rise to emergent narratives, where the events of the game are retold as a story. The goal of this thesis was to investigate ways to support the player in discovering their own emergent stories in grand strategy games. -

The Appendix Table the Most of Examinees Are Playing Strategies

The appendix table The most of examinees are playing strategies (RTS and History), Fantasy Role Play (FRP), simulations, adventures, RPG adventures, race, shooter, and some of them also play memory games. 1. Table: The results from questionnaire which came to life in practice between pupils from high schools in Petnica Science Center, Valjevo, and undergraduate students from first to third year and on the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Belgrade’s, Department of History, section for Medieval National studies. What do you think about education throw games? 17,65% Bad material for studying, with lot of mistakes and misleads; and with no or little validity of historical data. 82,35% It could be useful, for firsthand experience, the idea is not bad, one must think about that time, the strategies are good because you can see and think in the same time, one can easily put himself in a particular time, it could be good if you could have adequate program for learning, it is possible to use games like supplement, but not like a main source of information. Did you learn The realistic outlook of army units, about military formations and their something strategy, few things about architecture, ideology systems, about Hellenisms from the states, and also Islamic in medieval period, about medieval Spain, about games and treaties and conquests in period 1936–1948, about functioning Rome’s from which administration, Fredric I Barbarossa, about struggles in medieval England, ones? relationships between Poland and Lithuania, some maps are very good, the history of aviation in the First World War. -

First Amendment Protection of Artistic Entertainment: Toward Reasonable Municipal Regulation of Video Games

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 36 Issue 5 Issue 5 - October 1983 Article 2 10-1983 First Amendment Protection of Artistic Entertainment: Toward Reasonable Municipal Regulation of Video Games John E. Sullivan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the First Amendment Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation John E. Sullivan, First Amendment Protection of Artistic Entertainment: Toward Reasonable Municipal Regulation of Video Games, 36 Vanderbilt Law Review 1223 (1983) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol36/iss5/2 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE First Amendment Protection of Artistic Entertainment: Toward Reasonable Municipal Regulation of Video Games Outline I. INTRODUCTION .................................. 1225 II. LOCAL GOVERNMENT REGULATION OF VIDEO GAMES . 1232 A. Zoning Regulation ......................... 1232 1. Video Games Permitted by Right ........ 1232 2. Video Games as Conditional or Special U ses .................................. 1233 3. Video Games as Accessory Uses ......... 1234 4. Special Standards for Establishments Of- fering Video Game Entertainment ....... 1236 a. Age of Players and Hours of Opera- tion Standards .................. 1236 b. Arcade Space and Structural Stan- dards ........................... 1237 c. Arcade Location Standards....... 1237 d. Noise, Litter, and Parking Stan- dards ........................... 1238 e. Adult Supervision Standards ..... 1239 B. Licensing Regulation ....................... 1239 1. Licensing and Zoning Distinguished ...... 1239 2. Video Game Licensing Standards ........ 1241 3. Administration of Video Game Licensing. 1242 a. Denial of a License ............. -

Strategy Games Big Huge Games • Bruce C

04 3677_CH03 6/3/03 12:30 PM Page 67 Chapter 3 THE EXPERTS • Sid Meier, Firaxis General Game Design: • Bill Roper, Blizzard North • Brian Reynolds, Strategy Games Big Huge Games • Bruce C. Shelley, Ensemble Studios • Peter Molyneux, Do you like to use some brains along with (or instead of) brawn Lionhead Studios when gaming? This chapter is for you—how to create breathtaking • Alex Garden, strategy games. And do we have a roundtable of celebrities for you! Relic Entertainment Sid Meier, Firaxis • Louis Castle, There’s a very good reason why Sid Meier is one of the most Electronic Arts/ accomplished and respected game designers in the business. He Westwood Studios pioneered the industry with a number of unprecedented instant • Chris Sawyer, Freelance classics, such as the very first combat flight simulator, F-15 Strike Eagle; then Pirates, Railroad Tycoon, and of course, a game often • Rick Goodman, voted the number one game of all time, Civilization. Meier has con- Stainless Steel Studios tributed to a number of chapters in this book, but here he offers a • Phil Steinmeyer, few words on game inspiration. PopTop Software “Find something you as a designer are excited about,” begins • Ed Del Castillo, Meier. “If not, it will likely show through your work.” Meier also Liquid Entertainment reminds designers that this is a project that they’ll be working on for about two years, and designers have to ask themselves whether this is something they want to work on every day for that length of time. From a practical point of view, Meier says, “You probably don’t want to get into a genre that’s overly exhausted.” For me, working on SimGolf is a fine example, and Gettysburg is another—something I’ve been fascinated with all my life, and it wasn’t mainstream, but was a lot of fun to write—a fun game to put together. -

Drivers and Barriers to Adopting Gamification: Teachers' Perspectives

Drivers and Barriers to Adopting Gamification: Teachers’ Perspectives Antonio Sánchez-Mena1 and José Martí-Parreño*2 1HR Manager- Universidad Europea de Valencia, Valencia, Spain and Universidad Europea de Canarias, Tenerife, Spain 2Associate Professor - Universidad Europea de Valencia, Valencia, Spain [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: Gamification is the use of game design elements in non-game contexts and it is gaining momentum in a wide range of areas including education. Despite increasing academic research exploring the use of gamification in education little is known about teachers’ main drivers and barriers to using gamification in their courses. Using a phenomenology approach, 16 online structured interviews were conducted in order to explore the main drivers that encourage teachers serving in Higher Education institutions to using gamification in their courses. The main barriers that prevent teachers from using gamification were also analysed. Four main drivers (attention-motivation, entertainment, interactivity, and easiness to learn) and four main barriers (lack of resources, students’ apathy, subject fit, and classroom dynamics) were identified. Results suggest that teachers perceive the use of gamification both as beneficial but also as a potential risk for classroom atmosphere. Managerial recommendations for managers of Higher Education institutions, limitations of the study, and future research lines are also addressed. Keywords: gamification, games and learning, drivers, barriers, teachers, Higher Education. 1. Introduction Technological developments and teaching methodologies associated with them represent new opportunities in education but also a challenge for teachers of Higher Education institutions. Teachers must face questions regarding whether to implement new teaching methodologies in their courses based on their beliefs on expected outcomes, performance, costs, and benefits. -

Torin's Passage Manual

An Adventure Game by A1 Lowe Copyright 1995 by Sierra On-Line, Inc I Table of Contents First Time Installation ........................................3 How To Play The Game ...................................... 4 The Table of Contents Screen ...............................4 The Game Controls ......................................6 TheMenuBar .......................................... 9 Game Strategy ......................................... 11 Credits .................................................. 12 TheTeam ............................................ 12 . An~mat~on............................................ 14 Special Thanks To ...................................... 15 TheCast ............................................. 16 How To Contact Sierra ......................................17 Technical Support ...................................... 17 Direct Sales ........................................... 19 Hints ................................................ 20 International Support Services ..............................22 The Sierra No-Risk Guarantee .................................24 Warranty ................................................ 24 The Torin: Panage Team ...............................Back Cover First Time Installation Windowsm95 Installation 1. Start Windows'" 95. 2. Insert the Torin; Passage disk into your CD-ROM drive. 3. Follow the on-screen instructions. Windowsm3.1 + 1. Start Windows'"'. 2. Insert the Torin; Passage disk into your CD-ROM drive. 3. From the [File] menu, select [Run]. 4. Type "D:\SETUPEXEn -

Edutainment Case Study

What in the World Happened to Carmen Sandiego? The Edutainment Era: Debunking Myths and Sharing Lessons Learned Carly Shuler The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop Fall 2012 1 © The Joan Ganz Cooney Center 2012. All rights reserved. The mission of the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop is to harness digital media teChnologies to advanCe Children’s learning. The Center supports aCtion researCh, enCourages partnerships to ConneCt Child development experts and educators with interactive media and teChnology leaders, and mobilizes publiC and private investment in promising and proven new media teChnologies for Children. For more information, visit www.joanganzCooneyCenter.org. The Joan Ganz Cooney Center has a deep Commitment toward dissemination of useful and timely researCh. Working Closely with our Cooney Fellows, national advisors, media sCholars, and praCtitioners, the Center publishes industry, poliCy, and researCh briefs examining key issues in the field of digital media and learning. No part of this publiCation may be reproduCed or transmitted in any form or by any means, eleCtroniC or meChaniCal, inCluding photoCopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. For permission to reproduCe exCerpts from this report, please ContaCt: Attn: PubliCations Department, The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop One Lincoln Plaza New York, NY 10023 p: 212 595 3456 f: 212 875 7308 [email protected] Suggested Citation: Shuler, C. (2012). Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? The Edutainment Era: Debunking Myths and Sharing Lessons Learned. New York: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. -

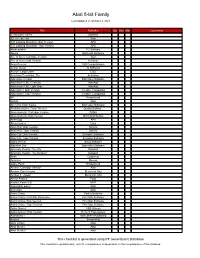

Atari 8-Bit Family

Atari 8-bit Family Last Updated on October 2, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 221B Baker Street Datasoft 3D Tic-Tac-Toe Atari 747 Landing Simulator: Disk Version APX 747 Landing Simulator: Tape Version APX Abracadabra TG Software Abuse Softsmith Software Ace of Aces: Cartridge Version Atari Ace of Aces: Disk Version Accolade Acey-Deucey L&S Computerware Action Quest JV Software Action!: Large Label OSS Activision Decathlon, The Activision Adventure Creator Spinnaker Software Adventure II XE: Charcoal AtariAge Adventure II XE: Light Gray AtariAge Adventure!: Disk Version Creative Computing Adventure!: Tape Version Creative Computing AE Broderbund Airball Atari Alf in the Color Caves Spinnaker Software Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves Quality Software Alien Ambush: Cartridge Version DANA Alien Ambush: Disk Version Micro Distributors Alien Egg APX Alien Garden Epyx Alien Hell: Disk Version Syncro Alien Hell: Tape Version Syncro Alley Cat: Disk Version Synapse Software Alley Cat: Tape Version Synapse Software Alpha Shield Sirius Software Alphabet Zoo Spinnaker Software Alternate Reality: The City Datasoft Alternate Reality: The Dungeon Datasoft Ankh Datamost Anteater Romox Apple Panic Broderbund Archon: Cartridge Version Atari Archon: Disk Version Electronic Arts Archon II - Adept Electronic Arts Armor Assault Epyx Assault Force 3-D MPP Assembler Editor Atari Asteroids Atari Astro Chase Parker Brothers Astro Chase: First Star Rerelease First Star Software Astro Chase: Disk Version First Star Software Astro Chase: Tape Version First Star Software Astro-Grover CBS Games Astro-Grover: Disk Version Hi-Tech Expressions Astronomy I Main Street Publishing Asylum ScreenPlay Atari LOGO Atari Atari Music I Atari Atari Music II Atari This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Well, She Sneaks Around the World from Kiev to Carolina She's a Sticky

1, 2, 3, yeah! Well, she sneaks around the world from Kiev to Carolina She's a sticky-fingered filcher from Berlin down to Belize She'll take you for a ride on a slow boat to China Tell me, where in the world is Carmen Sandiego? Steal their Seoul in South Korea, make Antarctica cry "Uncle!" From the Red Sea to Greenland, they'll be singing the blues Well, they never Arkansas her steal the Mekong from the jungle Tell me, where in the world is Carmen Sandiego? She'll go from Nashville to Norway, Bonaire to Zimbabwe Chicago, to Czechoslovakia* and back! Well, she'll ransack Pakistan, and run a scam in Scandinavia Then she'll stick 'em up down under and go pick-pocket Perth She put the "miss" in misdemeanor when she stole the beans from Lima Tell me, where in the world is Carmen Sandiego? Whoa, tell me where in the world? Hey! Come on, tell me where can she be? Botswana to Thailand, Milan via Amsterdam Mali, to Bali, Ohio, Oa-wa-hu! Aaahhhh!** The warrant, the warrant** The warrant, ba-ba-ba-ba-the warrant** Ooh, the chase** Ooh-woo-woo-woo, the chase** Monday through Friday at 5! Well, she glides around the globe, and she'll flim-flam every nation She's a double-dealing diva with a taste for thievery Her itinerary's loaded up with moving violations Tell me, where in the world is Carmen Sandiego? Whoa, tell me, where in the world is Carmen Sandiego? Tell me, where in the world is Carmen Sandiego? Tell me, where in the world is Carmen Sandiego? Tell me, where in the world is Carmen Sandiego? Tell me, where in the world is Where can she be, yeah? Whoa, where in the world is Carmen Sandiego? Tell me, where in the world is Carmen Sandiego? Watch your back! >> Look at a book about rocket ships.