Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and Its Multifarious Enemies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

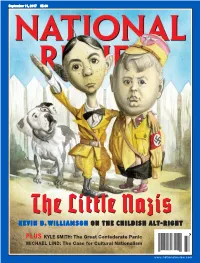

The Little Nazis KE V I N D

20170828 subscribers_cover61404-postal.qxd 8/22/2017 3:17 PM Page 1 September 11, 2017 $5.99 TheThe Little Nazis KE V I N D . W I L L I A M S O N O N T H E C HI L D I S H A L T- R I G H T $5.99 37 PLUS KYLE SMITH: The Great Confederate Panic MICHAEL LIND: The Case for Cultural Nationalism 0 73361 08155 1 www.nationalreview.com base_new_milliken-mar 22.qxd 1/3/2017 5:38 PM Page 1 !!!!!!!! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! "e Reagan Ranch Center ! 217 State Street National Headquarters ! 11480 Commerce Park Drive, Santa Barbara, California 93101 ! 888-USA-1776 Sixth Floor ! Reston, Virginia 20191 ! 800-USA-1776 TOC-FINAL_QXP-1127940144.qxp 8/23/2017 2:41 PM Page 1 Contents SEPTEMBER 11, 2017 | VOLUME LXIX, NO. 17 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 22 Lucy Caldwell on Jeff Flake The ‘N’ Word p. 15 Everybody is ten feet tall on the BOOKS, ARTS Internet, and that is why the & MANNERS Internet is where the alt-right really lives, one big online 35 THE DEATH OF FREUD E. Fuller Torrey reviews Freud: group-therapy session The Making of an Illusion, masquerading as a political by Frederick Crews. movement. Kevin D. Williamson 37 ILLUMINATIONS Michael Brendan Dougherty reviews Why Buddhism Is True: The COVER: ROMAN GENN Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment, ARTICLES by Robert Wright. DIVIDED THEY STAND (OR FALL) by Ramesh Ponnuru 38 UNJUST PROSECUTION 12 David Bahnsen reviews The Anti-Trump Republicans are not facing their challenges. -

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: to Stop the Defamation of the Jewish People and to Secure Justice and Fair Treatment for All

A report from the Center on Extremism 09 18 New Hate and Old: The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: To stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment for all. ABOUT T H E CENTER ON EXTREMISM The ADL Center on Extremism (COE) is one of the world’s foremost authorities ADL (Anti-Defamation on extremism, terrorism, anti-Semitism and all forms of hate. For decades, League) fights anti-Semitism COE’s staff of seasoned investigators, analysts and researchers have tracked and promotes justice for all. extremist activity and hate in the U.S. and abroad – online and on the ground. The staff, which represent a combined total of substantially more than 100 Join ADL to give a voice to years of experience in this arena, routinely assist law enforcement with those without one and to extremist-related investigations, provide tech companies with critical data protect our civil rights. and expertise, and respond to wide-ranging media requests. Learn more: adl.org As ADL’s research and investigative arm, COE is a clearinghouse of real-time information about extremism and hate of all types. COE staff regularly serve as expert witnesses, provide congressional testimony and speak to national and international conference audiences about the threats posed by extremism and anti-Semitism. You can find the full complement of COE’s research and publications at ADL.org. Cover: White supremacists exchange insults with counter-protesters as they attempt to guard the entrance to Emancipation Park during the ‘Unite the Right’ rally August 12, 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia. -

Culture Wars' Reloaded: Trump, Anti-Political Correctness and the Right's 'Free Speech' Hypocrisy

The 'Culture Wars' Reloaded: Trump, Anti-Political Correctness and the Right's 'Free Speech' Hypocrisy Dr. Valerie Scatamburlo-D'Annibale University of Windsor, Windsor, Ontario, Canada Abstract This article explores how Donald Trump capitalized on the right's decades-long, carefully choreographed and well-financed campaign against political correctness in relation to the broader strategy of 'cultural conservatism.' It provides an historical overview of various iterations of this campaign, discusses the mainstream media's complicity in promulgating conservative talking points about higher education at the height of the 1990s 'culture wars,' examines the reconfigured anti- PC/pro-free speech crusade of recent years, its contemporary currency in the Trump era and the implications for academia and educational policy. Keywords: political correctness, culture wars, free speech, cultural conservatism, critical pedagogy Introduction More than two years after Donald Trump's ascendancy to the White House, post-mortems of the 2016 American election continue to explore the factors that propelled him to office. Some have pointed to the spread of right-wing populism in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis that culminated in Brexit in Europe and Trump's victory (Kagarlitsky, 2017; Tufts & Thomas, 2017) while Fuchs (2018) lays bare the deleterious role of social media in facilitating the rise of authoritarianism in the U.S. and elsewhere. Other 69 | P a g e The 'Culture Wars' Reloaded: Trump, Anti-Political Correctness and the Right's 'Free Speech' Hypocrisy explanations refer to deep-rooted misogyny that worked against Hillary Clinton (Wilz, 2016), a backlash against Barack Obama, sedimented racism and the demonization of diversity as a public good (Major, Blodorn and Blascovich, 2016; Shafer, 2017). -

The Alt-Right Comes to Power by JA Smith

USApp – American Politics and Policy Blog: Long Read Book Review: Deplorable Me: The Alt-Right Comes to Power by J.A. Smith Page 1 of 6 Long Read Book Review: Deplorable Me: The Alt- Right Comes to Power by J.A. Smith J.A Smith reflects on two recent books that help us to take stock of the election of President Donald Trump as part of the wider rise of the ‘alt-right’, questioning furthermore how the left today might contend with the emergence of those at one time termed ‘a basket of deplorables’. Deplorable Me: The Alt-Right Comes to Power Devil’s Bargain: Steve Bannon, Donald Trump and the Storming of the Presidency. Joshua Green. Penguin. 2017. Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right. Angela Nagle. Zero Books. 2017. Find these books: In September last year, Hillary Clinton identified within Donald Trump’s support base a ‘basket of deplorables’, a milieu comprising Trump’s newly appointed campaign executive, the far-right Breitbart News’s Steve Bannon, and the numerous more or less ‘alt right’ celebrity bloggers, men’s rights activists, white supremacists, video-gaming YouTubers and message board-based trolling networks that operated in Breitbart’s orbit. This was a political misstep on a par with putting one’s opponent’s name in a campaign slogan, since those less au fait with this subculture could hear only contempt towards anyone sympathetic to Trump; while those within it wore Clinton’s condemnation as a badge of honour. Bannon himself was insouciant: ‘we polled the race stuff and it doesn’t matter […] It doesn’t move anyone who isn’t already in her camp’. -

178 Chapter 6 the Closing of the Kroll: Weimar

Chapter 6 The Closing of the Kroll: Weimar Culture and the Depression The last chapter discussed the Kroll Opera's success, particularly in the 1930-31 season, in fulfilling its mission as a Volksoper. While the opera was consolidating its aesthetic identity, a dire economic situation dictated the closing of opera houses and theaters all over Germany. The perennial question of whether Berlin could afford to maintain three opera houses on a regular basis was again in the air. The Kroll fell victim to the state's desire to save money. While the closing was not a logical choice, it did have economic grounds. This chapter will explore the circumstances of the opera's demise and challenge the myth that it was a victim of the political right. The last chapter pointed out that the response of right-wing critics to the Kroll was multifaceted. Accusations of "cultural Bolshevism" often alternated with serious appraisal of the strengths and weaknesses of any given production. The right took issue with the Kroll's claim to represent the nation - hence, when the opera tackled works by Wagner and Beethoven, these efforts were more harshly criticized because they were perceived as irreverent. The scorn of the right for the Kroll's efforts was far less evident when it did not attempt to tackle works crucial to the German cultural heritage. Nonetheless, political opposition did exist, and it was sometimes expressed in extremely crude forms. The 1930 "Funeral Song of the Berlin Kroll Opera", printed in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, may serve as a case in point. -

November-December 1966, Vol. XVIII, No. 1

t % AIR UNIVERSITY Heview Alr Ur|iversity Librar> MOV ' 9 1956 ' r^xwell AFB, A/a. 3611 f. eme act>©n USAF’S ROLE IN LATIN AMERICA: MILITARY ASSISTANCE, EDUCATION, AND PREVENTIVE MEDICINE CIVIC ACTION NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 1966 W hy Mil it a h y Assist a n c e for Latin Amer ica ? .....................................................................................2 Col. Frank R. Pancake, usaf (Ret) T he Lvter-Amer ica n Air Forces Academy........................................................................................... 13 Dr. A. Glenn Morton Preventive Med ic in e Civ ic Action Trainixc P rocram.........................................................................21 Maj. Mathew T. Dunn, usaf Maj. James B. Jones, usaf T he Spe c t r u m Construct of Conflict..............................................................................................................30 Norman Precoda Axa l ysis and Technology........................................................................................................................................45 Maj. Paul L. Gray, usaf Melvin Tanchel F rench Nuclear Wea pon s Policy...........................................................................................................................55 Lt. Col. Norman D. Eaton, usaf Aer o xa ut ica l Ge r ia t r ic s..............................................................................................................................................62 Col. I. R. Perkin, usaf Satellite Ground Tracks...................................................................................................................................... -

Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty's Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism

Ash Center Occasional Papers Tony Saich, Series Editor Something Has Cracked: Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty’s Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism Joshua Forstenzer University of Sheffield (UK) July 2018 Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation Harvard Kennedy School Ash Center Occasional Papers Series Series Editor Tony Saich Deputy Editor Jessica Engelman The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excellence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, education, and public discussion. By training the very best leaders, developing powerful new ideas, and disseminating innovative solutions and institutional reforms, the Center’s goal is to meet the profound challenges facing the world’s citizens. The Ford Foundation is a founding donor of the Center. Additional information about the Ash Center is available at ash.harvard.edu. This research paper is one in a series funded by the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. The views expressed in the Ash Center Occasional Papers Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or of Harvard University. The papers in this series are intended to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. This paper is copyrighted by the author(s). It cannot be reproduced or reused without permission. Ash Center Occasional Papers Tony Saich, Series Editor Something Has Cracked: Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty’s Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism Joshua Forstenzer University of Sheffield (UK) July 2018 Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation Harvard Kennedy School Letter from the Editor The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excellence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, education, and public discussion. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents The Opening Salvo 21 What Are Negotiations? 21 Why Are Negotiations Important? 25 When Do Negotiations Take Place? 26 Are Negotiations Limited to the Purview of Rocket Scientists? 30 Should Negotiators Always Seek to Vanquish Opponents? 31 Costs and Risks of Negotiations 36 Some Negotiators are Duplicitous 45 Risks of Borrowing Money from Partners and Customers 47 Avoiding Negotiations 63 You Are Always Negotiating 63 Fundamental Tensions in Negotiations 67 Negotiations Are Pervasive and Eternal 74 LEVERAGE IN NEGOTIATIONS 79 The Importance of Leverage in Negotiations 80 Creating Negotiating Leverage 85 Plan Your Exit at the Beginning 85 Importance of Choosing Partners Wisely 87 Gaining Leverage Through Third Parties 89 Business Models Are a Factor in Successful Negotiations 93 The Anatomy of Argumentation 97 Lincolnian Argumentation 98 The Power of Process 101 Harmonizing the Negotiating Process 103 Voting Architecture 105 Selected Negotiating Process Issues 107 Preemptively Setting the Framework for Resolving Disputes 108 Auctions Versus Direct Negotiations 113 Benefits of Auctions Over Direct Negotiations 113 Benefits of Direct Negotiations Over Auctions 115 The Strategic Negotiator I 1 Sequencing Negotiations 118 Sequencing Contentious Issues 118 Negotiating Downrange 129 Hold-Up Tactics 132 PREPARING FOR NEGOTIATIONS 143 Conducting Due Diligence on Individuals 148 Conducting Due Diligence on Institutions 152 Conducting Due Diligence on Individuals Within Institutions 154 Elicitation Strategies 157 Heimlich Maneuvers -

Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives $6.95

CANADIAN CENTRE FOR POLICY ALTERNATIVES MAY/JUNE 2018 $6.95 Contributors Ricardo Acuña is Director of Alex Himelfarb is a former Randy Robinson is a the Parkland Institute and federal government freelance researcher, sits on the CCPA’s Member’s executive with the Privy educator and political Council. Council, Treasury Board, and commentator based in Vol. 25, No. 1 numerous other departments, Toronto. Alyssa O’Dell is Media and ISSN 1198-497X and currently chairs or serves Public Relations Officer at the Luke Savage writes and Canada Post Publication 40009942 on various voluntary boards. CCPA. blogs about politics, labour, He chairs the advisory board The Monitor is published six times philosophy and political a year by the Canadian Centre for Marc Edge is a professor of of the CCPA-Ontario. culture. Policy Alternatives. media and communication Elaine Hughes is an at University Canada West Edgardo Sepulveda is an The opinions expressed in the environmental activist in in Vancouver. His last book, independent consulting Monitor are those of the authors several non-profit groups and do not necessarily reflect The News We Deserve: The economist with more than including the Council of the views of the CCPA. Transformation of Canada’s two decades of utility Canadians, where she chairs Media Landscape, was (telecommunications) policy Please send feedback to the Quill Plains (Wynyard), published by New Star Books and regulatory experience. [email protected]. Saskatchewan chapter. in 2016. He writes about electricity, Editor: Stuart Trew Syed Hussan is Co-ordinator inequality and other Senior Designer: Tim Scarth Matt Elliott is a city columnist of the Migrant Workers economic policy issues at Layout: Susan Purtell and blogger with Metro Editorial Board: Peter Bleyer, Alliance for Change. -

Section 6 Language Corrected SN(1)

The Socio-Cultural Conditions of the Avant-Gardes in Finland in the 1920s and 1930s Stefan Nygård Abstract As a geopolitically strategic and newly independent country recovering from the trauma of a civil war in 1918, the socio-cultural constraints on artistic freedom were considerable in Finland between the wars. Art and literature were to a varying extent connected to political projects on the left or the right. Leading critics played a key role in the negotiations between art, politics and ideology. Few artists or writers, however, adjusted uncritically to external ideological demands. Those that challenged the subordination of art to political agendas or the national imperative often relied on the accumulation of symbolic capital abroad. With its separation from Russia in the winter of 1917–1918, and a civil war that involved active participation from German and Russian troops, Finland was more directly affected by World War I than its Scandinavian neighbours. The climate of post-war cultural and intellectual debate was partly determined by the violent beginning of independence, in addition to the increasingly totalising claims of the state throughout Europe between the wars. At the time Finland was a semi-democratic country with relative freedom of expression. Socialist parties were only partially tolerated, and approximately 4,000 people were sentenced in the so-called communist trials between 1919 and 1944 (Björne 2007: 498–499). Besides the tension between east and west and “red” and “white”, linguistic struggles between Finnish and Swedish added to the disintegrating forces. In the context of a desperate search for national unity and political stability in what is sometimes called the “white republic”, there was limited tolerance for the kind of radical questioning of core values in liberal bourgeois society that was common among the early twentieth-century avant-gardes. -

Lecture Misinformation

Quote of the Day: “A lie will go round the world while truth is pulling its boots on.” -- Baptist preacher Charles H. Spurgeon, 1859 Please fill out the course evaluations: https://uw.iasystem.org/survey/233006 Questions on the final paper Readings for next time Today’s class: misinformation and conspiracy theories Some definitions of fake news: • any piece of information Donald Trump dislikes more seriously: • “a type of yellow journalism or propaganda that consists of deliberate disinformation or hoaxes spread via traditional news media (print and broadcast) or online social media.” disinformation: “false information which is intended to mislead, especially propaganda issued by a government organization to a rival power or the media” misinformation: “false or inaccurate information, especially that which is deliberately intended to deceive” Some findings of recent research on fake news, disinformation, and misinformation • False news stories are 70% more likely to be retweeted than true news stories. The false ones get people’s attention (by design). • Some people inadvertently spread fake news by saying it’s false and linking to it. • Much of the fake news from the 2016 election originated in small-time operators in Macedonia trying to make money (get clicks, sell advertising). • However, Russian intelligence agencies were also active (Kate Starbird’s research). The agencies created fake Black Lives Matter activists and Blue Lives Matter activists, among other profiles. A quick guide to spotting fake news, from the Freedom Forum Institute: https://www.freedomforuminstitute.org/first-amendment- center/primers/fake-news-primer/ Fact checking sites are also essential for identifying fake news.