178 Chapter 6 the Closing of the Kroll: Weimar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TURANDOT Cast Biographies

TURANDOT Cast Biographies Soprano Martina Serafin (Turandot) made her San Francisco Opera debut as the Marshallin in Der Rosenkavalier in 2007. Born in Vienna, she studied at the Vienna Conservatory and between 1995 and 2000 she was a member of the ensemble at Graz Opera. Guest appearances soon led her to the world´s premier opera stages, including at the Vienna State Opera where she has been a regular performer since 2005. Serafin´s repertoire includes the role of Lisa in Pique Dame, Sieglinde in Die Walküre, Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, the title role of Manon Lescaut, Lady Macbeth in Macbeth, Maddalena in Andrea Chénier, and Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni. Upcoming engagements include Elsa von Brabant in Lohengrin at the Opéra National de Paris and Abigaille in Nabucco at Milan’s Teatro alla Scala. Dramatic soprano Nina Stemme (Turandot) made her San Francisco Opera debut in 2004 as Senta in Der Fliegende Holländer, and has since returned to the Company in acclaimed performances as Brünnhilde in 2010’s Die Walküre and in 2011’s Ring cycle. Since her 1989 professional debut as Cherubino in Cortona, Italy, Stemme’s repertoire has included Rosalinde in Die Fledermaus, Mimi in La Bohème, Cio-Cio-San in Madama Butterfly, the title role of Manon Lescaut, Tatiana in Eugene Onegin, the title role of Suor Angelica, Euridice in Orfeo ed Euridice, Katerina in Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Countess in Le Nozze di Figaro, Marguerite in Faust, Agathe in Der Freischütz, Marie in Wozzeck, the title role of Jenůfa, Eva in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Elsa in Lohengrin, Amelia in Un Ballo in Machera, Leonora in La Forza del Destino, and the title role of Aida. -

Section 6 Language Corrected SN(1)

The Socio-Cultural Conditions of the Avant-Gardes in Finland in the 1920s and 1930s Stefan Nygård Abstract As a geopolitically strategic and newly independent country recovering from the trauma of a civil war in 1918, the socio-cultural constraints on artistic freedom were considerable in Finland between the wars. Art and literature were to a varying extent connected to political projects on the left or the right. Leading critics played a key role in the negotiations between art, politics and ideology. Few artists or writers, however, adjusted uncritically to external ideological demands. Those that challenged the subordination of art to political agendas or the national imperative often relied on the accumulation of symbolic capital abroad. With its separation from Russia in the winter of 1917–1918, and a civil war that involved active participation from German and Russian troops, Finland was more directly affected by World War I than its Scandinavian neighbours. The climate of post-war cultural and intellectual debate was partly determined by the violent beginning of independence, in addition to the increasingly totalising claims of the state throughout Europe between the wars. At the time Finland was a semi-democratic country with relative freedom of expression. Socialist parties were only partially tolerated, and approximately 4,000 people were sentenced in the so-called communist trials between 1919 and 1944 (Björne 2007: 498–499). Besides the tension between east and west and “red” and “white”, linguistic struggles between Finnish and Swedish added to the disintegrating forces. In the context of a desperate search for national unity and political stability in what is sometimes called the “white republic”, there was limited tolerance for the kind of radical questioning of core values in liberal bourgeois society that was common among the early twentieth-century avant-gardes. -

A Survey of the Career of Baritone, Josef Metternich: Artist and Teacher Diana Carol Amos University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2015 A Survey of the Career of Baritone, Josef Metternich: Artist and Teacher Diana Carol Amos University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Amos, D. C.(2015). A Survey of the Career of Baritone, Josef Metternich: Artist and Teacher. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3642 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SURVEY OF THE CAREER OF BARITONE, JOSEF METTERNICH: ARTIST AND TEACHER by Diana Carol Amos Bachelor of Music Oberlin Conservatory of Music, 1982 Master of Music University of South Carolina, 2011 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2015 Accepted by: Walter Cuttino, Major Professor Donald Gray, Committee Member Sarah Williams, Committee Member Janet E. Hopkins, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies ©Copyright by Diana Carol Amos, 2015 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I gratefully acknowledge the help of my professor, Walter Cuttino, for his direction and encouragement throughout this project. His support has been tremendous. My sincere gratitude goes to my entire committee, Professor Walter Cuttino, Dr. Donald Gray, Professor Janet E. Hopkins, and Dr. Sarah Williams for their perseverance and dedication in assisting me. -

Così Fan Tutte Cast Biography

Così fan tutte Cast Biography (Cahir, Ireland) Jennifer Davis is an alumna of the Jette Parker Young Artist Programme and has appeared at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden as Adina in L’Elisir d’Amore; Erste Dame in Die Zauberflöte; Ifigenia in Oreste; Arbate in Mitridate, re di Ponto; and Ines in Il Trovatore, among other roles. Following her sensational 2018 role debut as Elsa von Brabant in a new production of Lohengrin conducted by Andris Nelsons at the Royal Opera House, Davis has been propelled to international attention, winning praise for her gleaming, silvery tone, and dramatic characterisation of remarkable immediacy. (Sacramento, California) American Mezzo-soprano Irene Roberts continues to enjoy international acclaim as a singer of exceptional versatility and vocal suppleness. Following her “stunning and dramatically compelling” (SF Classical Voice) performances as Carmen at the San Francisco Opera in June, Roberts begins the 2016/2017 season in San Francisco as Bao Chai in the world premiere of Bright Sheng’s Dream of the Red Chamber. Currently in her second season with the Deutsche Oper Berlin, her upcoming assignments include four role debuts, beginning in November with her debut as Urbain in David Alden’s new production of Les Huguenots led by Michele Mariotti. She performs in her first Ring cycle in 2017 singing Waltraute in Die Walküre and the Second Norn in Götterdämmerung under the baton of Music Director Donald Runnicles, who also conducts her role debut as Hänsel in Hänsel und Gretel. Additional roles for Roberts this season include Rosina in Il barbiere di Siviglia, Fenena in Nabucco, Siebel in Faust, and the title role of Carmen at Deutsche Oper Berlin. -

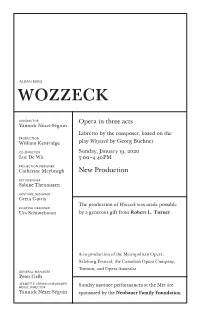

January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM

ALBAN BERG wozzeck conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by the composer, based on the production William Kentridge play Woyzeck by Georg Büchner co-director Sunday, January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM projection designer Catherine Meyburgh New Production set designer Sabine Theunissen costume designer Greta Goiris The production of Wozzeck was made possible lighting designer Urs Schönebaum by a generous gift from Robert L. Turner A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; Salzburg Festival; the Canadian Opera Company, Toronto; and Opera Australia general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Sunday matinee performances at the Met are Yannick Nézet-Séguin sponsored by the Neubauer Family Foundation 2019–20 SEASON The 75th Metropolitan Opera performance of ALBAN BERG’S wozzeck conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance the captain the fool Gerhard Siegel Brenton Ryan wozzeck a soldier Peter Mattei Daniel Clark Smith andres a townsman Andrew Staples Gregory Warren marie marie’s child Elza van den Heever Eliot Flowers margret Tamara Mumford* puppeteers Andrea Fabi the doctor Gwyneth E. Larsen Christian Van Horn ac tors the drum- major Frank Colardo Christopher Ventris Tina Mitchell apprentices Wozzeck is stage piano solo Richard Bernstein presented without Jonathan C. Kelly Miles Mykkanen intermission. Sunday, January 19, 2020, 3:00–4:40PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Berg’s Wozzeck Video Control Kim Gunning Assistant Video Editor Snezana Marovic Musical Preparation Caren Levine*, Jonathan C. Kelly, Patrick Furrer, Bryan Wagorn*, and Zalman Kelber* Assistant Stage Directors Gregory Keller, Sarah Ina Meyers, and J. -

William Dazeley Baritone

William Dazeley Baritone William Dazeley is a graduate of Jesus College, Cambridge. He studied singing at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, where he received several notable prizes including the prestigious Gold Medal, the Decca/Kathleen Ferrier Prize and the Richard Tauber Prize and won such competitions as the Royal Overseas League Singing Competition and the Walther Grüner International Lieder Competition. Engagements in the current season include MARCELLO La Boheme for Grange Park Opera, the world premiere of LIKE FLESH for the Opera de Lille and MUSIKLEHRER Ariadne auf Naxos for the Opera de Montpellier. Most recently, William sang DON ALFONSO Così fan tutte for the Royal Danish Opera, FATHER Hansel & Gretel in his company debut for Grange Park Opera, PROSECUTOR Frankenstein in the world premiere of Mark Grey’s opera Frankenstein at La Monnaie, COUNT Capriccio for Garsington Opera and PANDOLFE Cendrillon for Glyndebourne on Tour for whom he also appeared as CLAUDIUS in Brett Dean’s new award winning Hamlet. William has appeared in many of the world’s opera houses, where roles have included COUNT Cherubin, MARCELLO La Bohème, GUGLIELMO Così fan tutte, ANTHONY Sweeney Todd, YELETSKY Queen of Spades, MERCUTIO Romeo et Juliette and FIGARO Il Barbiere di Siviglia Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, PAPAGENO The Magic Flute English National Opera, ALFONSO Così fan tutte, Yeletsky, TITLE ROLE Don Giovanni, POSA Don Carlos, FANINAL Der Rosenkavalier, DANILO The Merry Widow, MR GEDGE Albert Herring Opera North, L’AMI The Fall of the -

Idomeneo” on Crete “

“Idomeneo” on Crete by Heather Mac Donald The humanists who created the first operas out to be his son, Idamante, whom, in Cam- in late sixteenth-century Florence hoped to re- pra’s opera, the king does indeed sacrifice be- capture the emotional impact of ancient Greek fore going mad. Such a dark ending no longer tragedy. It would take nearly another 200 years, suited Enlightenment tastes, however, and in however, for the most powerful aspect of Attic Mozart’s libretto, by the Salzburg cleric Giam- drama— the chorus—to reach its full potential battista Varesco, the gods grant Idomeneo a on an opera stage. That moment arrived with last-minute reprieve from his vow and rule is Mozart’s 1781 opera Idomeneo, re di Creta. This amicably passed from father to son. September, Opera San José performed Idome- The delight that Mozart must have had in neo’s sublime choruses with thrilling clarity and composing for the Mannheimers is palpable force, in a striking new production of the op- in Idomeneo’s dynamic score. And it is in the era that wedded a philanthropist’s archeologi- opera’s nine choruses that the orchestral writ- cal passion with his love for Mozart. San José’s ing reaches its pinnacle. In the celebrations Idomeneo was a reminder of the breadth of classi- of the Trojan War’s end—“Godiam la pace” cal music excellence in the United States, as well (“Let us savor peace”) and “Nettuno s’onori” as of the value of philanthropy guided by love. (“Let Neptune be honored”)—the strings In 1780, the twenty-four-year-old Mozart re- skitter jubilantly through complex rhythms ceived his most prestigious commission yet: to and rapid volume changes, while the winds compose an opera for the Court of Bavaria to embroider fleet counterpoint around the open Munich’s Carnival season. -

Music and Theatre in Eastern Europe: Understanding Historical Perspectives and Igniting Passion

Music and Theatre in Eastern Europe: Understanding Historical Perspectives and Igniting Passion January 7 – January 31, 2016 Hosted by Dr. Scott Johnson, Jayna Gearhart Fitzsimmons and Brad Heegel Program Inclusions v Experience the musical enrichment and fellowship traveling as part of a community under the leadership of Dr. Scott Johnson, Co-Chair of the College Department of Music who is both an accomplished musician and mentor; Jayna Gearhart Fitzsimmons, artistic director and experienced director of theater and Brad Heegel, Administrative Director of Performing and Visual Arts at Augustana who is both a seasoned traveler and energetic lead organizer for this program. v Be inspired by the culture and art of the Czech Republic with Prague’s royal palaces and museums; the beauty and music of Austria with the Vienna Boys Choir and Opera Houses; the grace and history of Slovakia with it’s amazing Slovak National Theatre; the vibrancy and heritage of Hungary in Budapest with collections of Art Nouveau and gypsy music; and lastly the history and open arms of Croatia in the town of Zagreb. v Attend eight concerts/performances and visit over forty famous sights and theatres in Europe. v Travel from Sioux Falls with connecting service into Prague and from Zagreb via United Airlines, Lufthansa Airlines and Croatian Airlines. v Stay for twenty-three nights in select Moderate First Class hotels described in the itinerary or similar, based on sharing a room. v Journey throughout Europe by private, deluxe motorcoach for all transfers and touring or by 2nd class rail. v Enjoy included daily buffet breakfast and six dinners. -

Austria & Hungary

AUSTRIA & HUNGARY June 17 -23 2018 A UNIQUE PERSPECTIVE OF THE MUSICAL, CULTURAL AND HISTORICAL HERITAGE OF VIENNA AND BUDAPEST Most of us have been to Austria and Hungary of course. But this Jaderin tour to Vienna, Eisenstadt, Graz, Salzburg and Budapest will be one with a big difference. We will be led by Maestro Mak Ka Lok who had studied, lived and actively conducted all over Austria, Russia and other parts of Europe for 30 years. The Maestro will be returning to Vienna in June with the Global Symphony Orchestra of Hong Kong, to receive the prestigious Austria Music and Theatre award for his contribution in music between Austria and China/Hong Kong. He will share his passion for music and the places he called home for many years on this special Jaderin tour covering Vienna : The beautiful capital of Austria that inspired so many composers. The visit includes the most celebrated river in Europe, Danube River,” the Wachau”, the Schönbrunn Palace where Mozart performed when he was a child. Enjoy an opera at the Vienna State Opera House Salzburg : In visiting the birthplace of Mozart, we will pass by the beautiful lake region “Salzkammergut” Eisenstadt : Pay homage to Haydn Graz: Attend Maestro’s Mak’s special “Austrian Music Theater Award” ceremony at the Opera House in Graz Budapest : Vienna and Budapest were the capitals of the Austrian Hungarian Empire from 1867 to 1918. Not only will you visit the Hungarian capital’s modern and historical sites, you will also ‘feel’ the flavors of Hungary, and taste authentic Hungarian Goulash. -

BERLIN SEMINAR June 9 to 18, 2021

BERLIN SEMINAR June 9 to 18, 2021 Designed with passionate scholars in mind, examine Prussian culture, Weimar-era decadence, World War II, the Cold War and reunification in Berlin during an up-close exploration of this storied European capital with history professor Jim Sheehan, ’58. FACULTY LEADER James Sheehan, ’58, is the Dickason Professor in the Humanities and professor emeritus of history at Stanford. His research focuses on 19th- and 20th-century European history, specifically on the relationship between ideas and social and economic conditions in modern Europe. His most recent book, Where Have All the Soldiers Gone?: The Transformation of Modern Europe, examines the decline of military institutions in Europe since 1945. He is now writing a book about the rise of European states in the modern era. About this program, Jim writes, “Berlin is one of the world’s great cities. In it, we encounter the past at every turn, in memorials and monuments, historic buildings and the ruined reminders of a troubled history. But contemporary Berlin is also full of life, music, art and excitement. Together we will explore Berlin’s past and present and the ways they interact and influence one another.” ● Dickason Professor in the Humanities, Stanford University ● Professor emeritus, department of history, Stanford University ● Senior fellow, by courtesy, Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, Stanford University ● Dean’s Award for Distinguished Teaching, Stanford University, 1993 ● Walter J. Gores Award for Excellence in Teaching, Stanford University, 1993 ● Guggenheim Fellow, 2000–2001 ● Fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences ● BA, 1958, Stanford University ● PhD, 1964, UC Berkeley ITINERARY Wednesday, June 9 Berlin, Germany Upon arrival in Berlin, transfer to our hotel, which is centrally located on the Gendarmenmarkt, an 18th- century town square that’s home to the Konzerthaus, the Huguenot Französischer Dom and the Deutscher Dom. -

The History of Europe — Told by Its Theatres

THE HISTORY OF EUROPE — TOLD BY ITS THEATRES Exhibition magazine CONTENT 4 Introductions We live in Europe, and it is therefore our task to make this part of the world work, in a peaceful way and for the best of all people liv - 6 Mediterranean experience ing here. To achieve this, we have to cooperate across borders, be - 10 religious impact cause only together we can solve the challenges we are facing together. For this, institutions are necessary that make cooperation 14 Changing society – possible on a permanent basis. For this, it is necessary to jointly changing building create an idea of how Europe shall develop now and in the future. 18 The Theatre royal, drury lane For this, it is necessary to remember where we come from – to remember our common history in Europe. 22 Max littmann For this, the touring exhibition The history of Europe – told by and the democratisation its theatres proposes a unique starting point: our theatres. And this of the auditorium is not a coincidence. Since the first ancient civilisations developed 24 Aesthetics and technology in Europe 2500 years ago, the history of Europe has also been the 28 The nation history of its theatre. For 2500 years, theatre performances have been reflecting our present, past and possible future. For the per - 34 Spirit of the nation set ablaze formances, this special form of a joint experience and of joint re - 38 To maintain the common flection, Europeans have developed special buildings that in turn identity – the Teatr Wielki mirror the development of society. And thus today we find theatre in Warsaw buildings from many eras everywhere in Europe. -

2018 2018 Juni Programm

Programm 2018 Juni Programmschwerpunkt ,Radfunk‘ Deutschlandfunk und 2018 Deutschlandfunk Nova Seite 3 Herr Raue 2 Editorial Inhalt 25 Jahre Radio 2 Editorial für Deutschland 3 Aktuell Programmschwerpunkt ,Radfunk‘ Liebe Hörerinnen und Hörer, 4 Musik für die Fans von öffentlich-rechtlichem Qualitätsjournalis- Die Indie-Band Carnival Youth Deutschlandradio/ Rued Langgaard: ‚Antikrist‘ © Bettina Fürst-Fastré mus ist der 17. Juni ein gutes Datum. Vor 25 Jahren unter- zeichneten Vertreter der zwölf damals alten und vier neuen Bundesländer den 8 Literatur Deutschlandradio-Staatsvertrag und legten damit die Grundlage für Deutsch- ‚Lesezeit‘ mit Monika Maron Der amerikanische Schriftsteller lands einzigen bundesweiten Radiosender. Unter seinem Dach fanden so unter- und Fotograf Teju Cole schiedliche Einrichtungen wie der Deutschlandfunk und RIAS (West) sowie der Deutschlandsender Kultur (Ost) zusammen mit ihren traditionsreichen Orches- 10 Feature Monatsübersicht/Tipps tern und Chören eine neue Heimat. Deutschlandradio ist damit wie kein anderer Sender ein Kind der deutschen Einheit. 14 Gastbeitrag Dr. Mathias Döpfner Deshalb wissen wir aus eigener Erfahrung: Das Gefühl des Zusammengehö- rens erzeugt man nicht, indem man einen Schalter umlegt. Zusammenwachsen 15 Programmkalender Juni 18 ist Arbeit. Es erfordert die Bereitschaft, interessiert auf den anderen zuzugehen, zuzuhören und auch die eigene Sichtweise infrage zu stellen. Genau das tun un- sere Landeskorrespondentinnen und -korrespondenten auch. Sender der Länder 78 Spezial zu sein bedeutet nämlich nicht nur, nah an den Menschen in der eigenen Region Alles rund um die Fußball-WM zu sein, sondern auch den Hörerinnen und Hörern in Aachen zu erklären, warum 79 Lange Nacht ein Thema aus Görlitz auch für sie Relevanz hat. Und den Nutzerinnen in Bremen Sprachwurzellos zu erklären, was die Nutzer in Konstanz bewegt.