Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

178 Chapter 6 the Closing of the Kroll: Weimar

Chapter 6 The Closing of the Kroll: Weimar Culture and the Depression The last chapter discussed the Kroll Opera's success, particularly in the 1930-31 season, in fulfilling its mission as a Volksoper. While the opera was consolidating its aesthetic identity, a dire economic situation dictated the closing of opera houses and theaters all over Germany. The perennial question of whether Berlin could afford to maintain three opera houses on a regular basis was again in the air. The Kroll fell victim to the state's desire to save money. While the closing was not a logical choice, it did have economic grounds. This chapter will explore the circumstances of the opera's demise and challenge the myth that it was a victim of the political right. The last chapter pointed out that the response of right-wing critics to the Kroll was multifaceted. Accusations of "cultural Bolshevism" often alternated with serious appraisal of the strengths and weaknesses of any given production. The right took issue with the Kroll's claim to represent the nation - hence, when the opera tackled works by Wagner and Beethoven, these efforts were more harshly criticized because they were perceived as irreverent. The scorn of the right for the Kroll's efforts was far less evident when it did not attempt to tackle works crucial to the German cultural heritage. Nonetheless, political opposition did exist, and it was sometimes expressed in extremely crude forms. The 1930 "Funeral Song of the Berlin Kroll Opera", printed in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, may serve as a case in point. -

A Survey of the Career of Baritone, Josef Metternich: Artist and Teacher Diana Carol Amos University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2015 A Survey of the Career of Baritone, Josef Metternich: Artist and Teacher Diana Carol Amos University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Amos, D. C.(2015). A Survey of the Career of Baritone, Josef Metternich: Artist and Teacher. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3642 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SURVEY OF THE CAREER OF BARITONE, JOSEF METTERNICH: ARTIST AND TEACHER by Diana Carol Amos Bachelor of Music Oberlin Conservatory of Music, 1982 Master of Music University of South Carolina, 2011 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2015 Accepted by: Walter Cuttino, Major Professor Donald Gray, Committee Member Sarah Williams, Committee Member Janet E. Hopkins, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies ©Copyright by Diana Carol Amos, 2015 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I gratefully acknowledge the help of my professor, Walter Cuttino, for his direction and encouragement throughout this project. His support has been tremendous. My sincere gratitude goes to my entire committee, Professor Walter Cuttino, Dr. Donald Gray, Professor Janet E. Hopkins, and Dr. Sarah Williams for their perseverance and dedication in assisting me. -

Così Fan Tutte Cast Biography

Così fan tutte Cast Biography (Cahir, Ireland) Jennifer Davis is an alumna of the Jette Parker Young Artist Programme and has appeared at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden as Adina in L’Elisir d’Amore; Erste Dame in Die Zauberflöte; Ifigenia in Oreste; Arbate in Mitridate, re di Ponto; and Ines in Il Trovatore, among other roles. Following her sensational 2018 role debut as Elsa von Brabant in a new production of Lohengrin conducted by Andris Nelsons at the Royal Opera House, Davis has been propelled to international attention, winning praise for her gleaming, silvery tone, and dramatic characterisation of remarkable immediacy. (Sacramento, California) American Mezzo-soprano Irene Roberts continues to enjoy international acclaim as a singer of exceptional versatility and vocal suppleness. Following her “stunning and dramatically compelling” (SF Classical Voice) performances as Carmen at the San Francisco Opera in June, Roberts begins the 2016/2017 season in San Francisco as Bao Chai in the world premiere of Bright Sheng’s Dream of the Red Chamber. Currently in her second season with the Deutsche Oper Berlin, her upcoming assignments include four role debuts, beginning in November with her debut as Urbain in David Alden’s new production of Les Huguenots led by Michele Mariotti. She performs in her first Ring cycle in 2017 singing Waltraute in Die Walküre and the Second Norn in Götterdämmerung under the baton of Music Director Donald Runnicles, who also conducts her role debut as Hänsel in Hänsel und Gretel. Additional roles for Roberts this season include Rosina in Il barbiere di Siviglia, Fenena in Nabucco, Siebel in Faust, and the title role of Carmen at Deutsche Oper Berlin. -

William Dazeley Baritone

William Dazeley Baritone William Dazeley is a graduate of Jesus College, Cambridge. He studied singing at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, where he received several notable prizes including the prestigious Gold Medal, the Decca/Kathleen Ferrier Prize and the Richard Tauber Prize and won such competitions as the Royal Overseas League Singing Competition and the Walther Grüner International Lieder Competition. Engagements in the current season include MARCELLO La Boheme for Grange Park Opera, the world premiere of LIKE FLESH for the Opera de Lille and MUSIKLEHRER Ariadne auf Naxos for the Opera de Montpellier. Most recently, William sang DON ALFONSO Così fan tutte for the Royal Danish Opera, FATHER Hansel & Gretel in his company debut for Grange Park Opera, PROSECUTOR Frankenstein in the world premiere of Mark Grey’s opera Frankenstein at La Monnaie, COUNT Capriccio for Garsington Opera and PANDOLFE Cendrillon for Glyndebourne on Tour for whom he also appeared as CLAUDIUS in Brett Dean’s new award winning Hamlet. William has appeared in many of the world’s opera houses, where roles have included COUNT Cherubin, MARCELLO La Bohème, GUGLIELMO Così fan tutte, ANTHONY Sweeney Todd, YELETSKY Queen of Spades, MERCUTIO Romeo et Juliette and FIGARO Il Barbiere di Siviglia Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, PAPAGENO The Magic Flute English National Opera, ALFONSO Così fan tutte, Yeletsky, TITLE ROLE Don Giovanni, POSA Don Carlos, FANINAL Der Rosenkavalier, DANILO The Merry Widow, MR GEDGE Albert Herring Opera North, L’AMI The Fall of the -

Idomeneo” on Crete “

“Idomeneo” on Crete by Heather Mac Donald The humanists who created the first operas out to be his son, Idamante, whom, in Cam- in late sixteenth-century Florence hoped to re- pra’s opera, the king does indeed sacrifice be- capture the emotional impact of ancient Greek fore going mad. Such a dark ending no longer tragedy. It would take nearly another 200 years, suited Enlightenment tastes, however, and in however, for the most powerful aspect of Attic Mozart’s libretto, by the Salzburg cleric Giam- drama— the chorus—to reach its full potential battista Varesco, the gods grant Idomeneo a on an opera stage. That moment arrived with last-minute reprieve from his vow and rule is Mozart’s 1781 opera Idomeneo, re di Creta. This amicably passed from father to son. September, Opera San José performed Idome- The delight that Mozart must have had in neo’s sublime choruses with thrilling clarity and composing for the Mannheimers is palpable force, in a striking new production of the op- in Idomeneo’s dynamic score. And it is in the era that wedded a philanthropist’s archeologi- opera’s nine choruses that the orchestral writ- cal passion with his love for Mozart. San José’s ing reaches its pinnacle. In the celebrations Idomeneo was a reminder of the breadth of classi- of the Trojan War’s end—“Godiam la pace” cal music excellence in the United States, as well (“Let us savor peace”) and “Nettuno s’onori” as of the value of philanthropy guided by love. (“Let Neptune be honored”)—the strings In 1780, the twenty-four-year-old Mozart re- skitter jubilantly through complex rhythms ceived his most prestigious commission yet: to and rapid volume changes, while the winds compose an opera for the Court of Bavaria to embroider fleet counterpoint around the open Munich’s Carnival season. -

BERLIN SEMINAR June 9 to 18, 2021

BERLIN SEMINAR June 9 to 18, 2021 Designed with passionate scholars in mind, examine Prussian culture, Weimar-era decadence, World War II, the Cold War and reunification in Berlin during an up-close exploration of this storied European capital with history professor Jim Sheehan, ’58. FACULTY LEADER James Sheehan, ’58, is the Dickason Professor in the Humanities and professor emeritus of history at Stanford. His research focuses on 19th- and 20th-century European history, specifically on the relationship between ideas and social and economic conditions in modern Europe. His most recent book, Where Have All the Soldiers Gone?: The Transformation of Modern Europe, examines the decline of military institutions in Europe since 1945. He is now writing a book about the rise of European states in the modern era. About this program, Jim writes, “Berlin is one of the world’s great cities. In it, we encounter the past at every turn, in memorials and monuments, historic buildings and the ruined reminders of a troubled history. But contemporary Berlin is also full of life, music, art and excitement. Together we will explore Berlin’s past and present and the ways they interact and influence one another.” ● Dickason Professor in the Humanities, Stanford University ● Professor emeritus, department of history, Stanford University ● Senior fellow, by courtesy, Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, Stanford University ● Dean’s Award for Distinguished Teaching, Stanford University, 1993 ● Walter J. Gores Award for Excellence in Teaching, Stanford University, 1993 ● Guggenheim Fellow, 2000–2001 ● Fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences ● BA, 1958, Stanford University ● PhD, 1964, UC Berkeley ITINERARY Wednesday, June 9 Berlin, Germany Upon arrival in Berlin, transfer to our hotel, which is centrally located on the Gendarmenmarkt, an 18th- century town square that’s home to the Konzerthaus, the Huguenot Französischer Dom and the Deutscher Dom. -

Abbie Furmansky

Abbie Furmansky American soprano Abbie Furmansky came to prominence while performing as an ensemble member at the Deutsche Oper Berlin, where she quickly established herself in the lyric repertoire. She is especially noted for her riveting stage presence, rich vocal timbre, musicality and expansive voice. She has worked with well-known conductors such as Kent Nagano, Ingo Metzmacher, Christopher Hogwood, John Nelson, Christian Thielemann and Edo de Waart. Throughout Europe and in the USA, she appeared with the German Symphony Orchestra, the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, the Berlin Radio Orchestra, and the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra, among many others. Further engagements led her to opera houses such as the New York City Opera, Canadian Opera Company, Washington National Opera, Los Angeles Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, Oper Frankfurt, de Nederlandse Opera and the Baden-Baden Festival. Concert performances include Britten’s War Requiem at the Berlin Philharmonic, Bernstein’s Kaddish Symphony at the Lucerne Festival, Beethoven-Strauss’ Die Ruinen von Athen with the Dresden Philharmonic, Frank Martin’s Golgotha in Potsdam, Beethoven’s 9th Symphony in Serbia, Mozart Arias with the Southwest Philharmonic Constance, and Mendelssohn’s Elijah with the Singapore Symphony Orchestra. From 2007 to 2010 Abbie Furmansky was a member of the ensemble at the Staatstheater Mainz, where she made her debuts as the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier, Jenny in Mahagonny, Mimì in La Bohème, Marie in Wozzeck and the title role in Madama Butterfly in a production by Katharina Wagner. As a recitalist she has performed in Zamora and Morelia, Mexico with the pianist Alexandr Pashkov, at the Deutsche Oper Berlin and the University of Wisconsin at Madison, with her husband Daniel Sutton. -

BERLIN UNDIVIDED Press Release Donald Runnicles

Donald Runnicles Press Release Medium Opera News Date March 2018 Author A. J. Goldmann Link h t t p s : //w w w . o p e r a n e w s . c o m /O p e r a _ N e w s _ M a g a z i n e/ 201 8 /3 / Features/Berlin_Undivided.html BERLIN UNDIVIDED The capital of Germany boasts unparalleled musical riches-including three opera companies. ON OCTOBER 3, BERLIN‘S HISTORIC STAATSOPER UNTER DEN LINDEN RE OPEN ED with Daniel Barenboim conducting Robert Schumann‘s Szenen aus Goethes Faust. lt was the house‘s first performance after being shuttered for renovations for seven years. In any other city on earth, this would have been the event of the year, if not the decade. In music-saturated Berlin, a city with three full-time opera companies and seven full-time orchestras, it seemed like just one highlight among many. When all is said and done, this season Berlin will see hundreds of performances of more than seventy-five different full productions, in- cluding twenty new stagings of works ranging from Monteverdi to world premieres. Four miles west of the Staatsoper is Deutsche Oper Berlin, a 105-ye- ar-old company known for big voices and grand operas, which fielded starry casts during the years when the city was divided. Founded in 1912, in what was then the independent township of Charlottenburg, it was designed as a „Winter Bayreuth“ to show Wagner‘s modern music dra- mas to best possible advantage. The city‘s third opera hause, Komische Oper-located, like the Staatsoper. -

Wojtek Gierlach Bass

Wojtek Gierlach Bass In the 2020/21 season, Polish bass Wojtek and sang Bach's Magnificat at Auditorio Gierlach returns again to Welsh National Opera Nacional de Madrid, Bruckner’s Te Deum and to sing the role of Mephistopheles in Faust. A Beethoven's Symphony No. 9 with the Ulster favourite at Polish National Opera, he also Orchestra in Belfast and his Missa solemnis with returns to Warsaw to sing The Gold Merchant in Helmuth Rilling at Konzerthaus Berlin, Salieri's Cardillac. The Passion of Jesus Christ with Solisti Veneti and Claudio Scimone and Rossini's Stabat Mater Last season at WNO, he made role debuts as with Orquesta del Principado de Asturias under Sparafucile Rigoletto, Parson The Cunning Alberto Zedda. He regularly performs Little Vixen and Procida in David Pountney’s Penderecki's music under the baton of the new production of Les vêpres siciliennes. composer, and has sung works including his Polish Requiem, Seven Gates of Jerusalem and In 2018/19 he sang Rocco Fidelio and Alidoro La Credo. A special performance of Penderecki’s Cenerentola at WNO, the latter being somewhat Dies Irae with the Simon Bolivar Orchestra led of a signature role for him, which he has also him to Caracas. performed with Festival d'Aix-en-Provence, Deutsche Oper Berlin and Teatro Maestranza in Wojtek’s large discography includes Mose in Seville. He also returned to the role of Figaro Le Egitto and La Donna del Lago, Meyerbeer's nozze di Figaro and sang Zbigniew Straszny Semiramide under Richard Bonynge, dwór at Teatr Wielki Poznań, and Penderecki’s Magnificat and Janacek’s Commendatore Don Giovanni for Opera Glagolithic Mass (all Naxos), G.S. -

Laure De Marcellus, Mezzo Soprano

LAURE DE MARCELLUS, MEZZO SOPRANO Laure de Marcellus’ velvety timbre and riveting stage presence delight both critics and audiences. She honed her craft at the Deutsche Oper, Berlin. She made her celebrated debut as CARMEN at the Fêtes de Genève and appeared as Dalila SAMSON ET DALILA for the Opéra Studio of Geneva’s 20th Anniversary, and for the Gabriel Fauré Festival in Annecy. She sang Brangäne in TRISTAN UND ISOLDE with the Norddeutches Philharmonie conducted by Peter Leonard. At the Deutsche Oper, she sang such diverse roles as Maddalena RIGOLETTO with Mikhail Jurowski, Grimgerde DIE WALKÜRE with Christian Thielemann, Smeton ANNA BOLENA, Mérope OEDIPE staged by Götz Friedrich who also directed her in his final production, AMAHL AND THE NIGHT VISITORS; Third Lady DIE ZAUBERFLÖTE, Flora LA TRAVIATA. Miss de Marcellus appeared in Berlin’s nationally televised anual gala for AIDS research under the baton of the late Marcello Viotti with Sumi Jo and Ramon Vargas. Other roles in Miss de Marcellus’ repertoire are Eboli, DON CARLO, Orsini LUCREZIA BORGIA, Fricka DIE WALKÜRE, Waltraute GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG, Erda RHEINGOLD, Federica LUISA MILLER, Sesto CLEMENZA DI TITO and Orlofsky DIE FLEDERMAUS. Her early roles include the title role ORFEO E EURIDICE and Eustazio RINALDO. Her collaboration with pianist Alberto Urroz is becoming a regular feature at Navarra’s Mendigorría Music Festival. After their last recital of a very well received program of songs by Schubert. Liszt and Fauré, they just performed a Schumann program to rave reviews, which they will reprise in Madrid and Geneva in March 2020 Her broad concert repertoire includes oratorios from VERDI REQUIEM to lesser-known works such as César Franck’s RÉDEMPTION or Britten’s NOAH’S ARK which she performed with Jun Märkl for Radio France. -

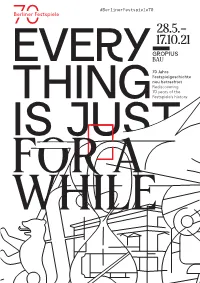

Everything Is Just for a While

#BerlinerFestspiele70 Berliner Festspiele70 28.5.– 17.10.21 GROPIUS BAU EVERY-70 Jahre Festspielgeschichte neu betrachtet Rediscovering 70 years of the THING Festspiele's history IS JUST FOR A WHILE Inhaltsverzeichnis / Table of contents INHALTS- VERZEICHNIS TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Vorwort Preface 12 Eine Geschichte der Berliner Festspiele A History of the Berliner Festspiele 40 Videoinstallationen Video installations 54 Filme Films 88 Impressum Imprint Everything Is Just for a While EVERYTHING IS JUST FOR A WHILE 70 Jahre Festspielgeschichte neu betrachtet Rediscovering 70 years of the Festspiele's history Vorwort / Preface Labor und Experiment, Seismograf des Zeitgeist, Ausstellungsort und Debattierklub, Radical Art und Workshops für Jugendliche, Feuer werk und Sport, wochenlang afrikanische Kunst, Städteplanung A laboratory and an experiment, und Autor*innenförderung, Wissen a seismograph of the zeitgeist, an schaftskolleg und Festumzug mit exhibition space and a debating Wasserkorso und immer wieder society, radical art and workshops for Plattform der internationalen Kunst young people, fireworks and sporting szene – all das waren die Berliner events, weeks of African art, urban Festspiele in den vergangenen 70 planning and new writing, an Institute Jahren. Im Geburtstagsjahr zeigt of Advanced Studies and a celebra „Everything Is Just for a While” tory waterborne procession, a recur einen Zusammenschnitt aus rent platform for the international bis lang kaum bekannten Be wegt art scene – over the last 70 years the bildern, ein Spiegelkabinett der Berliner Festspiele have been all of Erin ner ungen. Die Videoinstalla these things. In their birthday year, tionen werden von einer Infowand “Everything Is Just for a While” pre gerahmt, die die Identität und die s ents a compilation of previously Geschichte der Berliner Festspiele littleknown film footage, a hall veranschaulichen. -

The German Soprano Ricarda Merbeth Is One of the Leading Singers in Her Field and Is in Demand Worldwide As a Wagner and Strauss Interpreter

The German soprano Ricarda Merbeth is one of the leading singers in her field and is in demand worldwide as a Wagner and Strauss interpreter. After her studies at the Hochschule für Musik "Mendelssohn Bartholdy" in Leipzig she began her career in Magdeburg and Weimar. In 1999 she made her debut as Marzelline in Fidelio at the Vienna State Opera and was a member of the ensemble until 2005. Since then she has sung Contessa, Donna Anna, Pamina, Fiordiligi, Chrysothemis, Elisabeth, Eva, Irene, Elsa, Marschallin and Sieglinde. A special highlight in 2004 was her Daphne in a new production at the Vienna State Opera. With this title role by Richard Strauss, Ricarda Merbeth achieved an international breakthrough. The artist is still associated with the Vienna State Opera today through regular guest engagements. In 2001 she was honoured with the Eberhard Waechter Medal and in 2010 was appointed Austrian Chamber Singer. Further milestones of her career were engagements at the Bayreuth Festival: 2000 at the Jürgen Flimm-Ring as Freia and Gutrune, 2002 to 2005 and 2007 as Elisabeth in TANNHÄUSER and from 2013 to 2018 she sang the role of Senta in the production DER FLIEGENDE HOLLÄNDER. Since 2006 she has appeared as a freelance artist at the world's leading opera houses, including the Bayreuth Festival, Hamburg State Opera, Bavarian State Opera, Vienna State Opera, Milan Scala, Deutsche Oper Berlin, Staatsoper Unter den Linden Berlin, New National Theatre Tokyo, Opera Nationale de Paris, Teatro Real Madrid, Dutch National Opera, La Monnaie in Brussels, Royal Opera House in London. She sings all important roles in her field: Elektra, Helena, Ariadne, Marietta, Marschallin, Senta, Leonore, Emilia Marty, Elsa, Marie, Isolde, Goneril, Elisabeth and Venus, as well as the Brünnhilden in Wagner's Ring.