Version 2, 08/09/2017 20:48:33

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

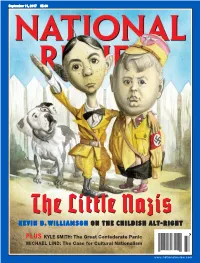

The Little Nazis KE V I N D

20170828 subscribers_cover61404-postal.qxd 8/22/2017 3:17 PM Page 1 September 11, 2017 $5.99 TheThe Little Nazis KE V I N D . W I L L I A M S O N O N T H E C HI L D I S H A L T- R I G H T $5.99 37 PLUS KYLE SMITH: The Great Confederate Panic MICHAEL LIND: The Case for Cultural Nationalism 0 73361 08155 1 www.nationalreview.com base_new_milliken-mar 22.qxd 1/3/2017 5:38 PM Page 1 !!!!!!!! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! "e Reagan Ranch Center ! 217 State Street National Headquarters ! 11480 Commerce Park Drive, Santa Barbara, California 93101 ! 888-USA-1776 Sixth Floor ! Reston, Virginia 20191 ! 800-USA-1776 TOC-FINAL_QXP-1127940144.qxp 8/23/2017 2:41 PM Page 1 Contents SEPTEMBER 11, 2017 | VOLUME LXIX, NO. 17 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 22 Lucy Caldwell on Jeff Flake The ‘N’ Word p. 15 Everybody is ten feet tall on the BOOKS, ARTS Internet, and that is why the & MANNERS Internet is where the alt-right really lives, one big online 35 THE DEATH OF FREUD E. Fuller Torrey reviews Freud: group-therapy session The Making of an Illusion, masquerading as a political by Frederick Crews. movement. Kevin D. Williamson 37 ILLUMINATIONS Michael Brendan Dougherty reviews Why Buddhism Is True: The COVER: ROMAN GENN Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment, ARTICLES by Robert Wright. DIVIDED THEY STAND (OR FALL) by Ramesh Ponnuru 38 UNJUST PROSECUTION 12 David Bahnsen reviews The Anti-Trump Republicans are not facing their challenges. -

The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: to Stop the Defamation of the Jewish People and to Secure Justice and Fair Treatment for All

A report from the Center on Extremism 09 18 New Hate and Old: The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: To stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment for all. ABOUT T H E CENTER ON EXTREMISM The ADL Center on Extremism (COE) is one of the world’s foremost authorities ADL (Anti-Defamation on extremism, terrorism, anti-Semitism and all forms of hate. For decades, League) fights anti-Semitism COE’s staff of seasoned investigators, analysts and researchers have tracked and promotes justice for all. extremist activity and hate in the U.S. and abroad – online and on the ground. The staff, which represent a combined total of substantially more than 100 Join ADL to give a voice to years of experience in this arena, routinely assist law enforcement with those without one and to extremist-related investigations, provide tech companies with critical data protect our civil rights. and expertise, and respond to wide-ranging media requests. Learn more: adl.org As ADL’s research and investigative arm, COE is a clearinghouse of real-time information about extremism and hate of all types. COE staff regularly serve as expert witnesses, provide congressional testimony and speak to national and international conference audiences about the threats posed by extremism and anti-Semitism. You can find the full complement of COE’s research and publications at ADL.org. Cover: White supremacists exchange insults with counter-protesters as they attempt to guard the entrance to Emancipation Park during the ‘Unite the Right’ rally August 12, 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia. -

Click Here to View a Sample Chapter of the Pandemic Population

2020 by Tim Elmore All rights reserved. You have beeN graNted the NoN-exclusive, NoN-traNsferable right to access aNd read the text of this e-book oN screeN. No parts of this book may be reproduced, traNsmitted, decompiled, reverse eNgiNeered, or stored iN or iNtroduced iNto aNy iNformatioN storage or retrieval system iN aNy form by aNy meaNs, whether electroNic or mechaNical, Now kNowN or hereiNafter iNveNted, without express writteN permissioN from the publisher. Published by AmazoN iN associatioN with GrowiNg Leaders, INc. PandemicPopulation.com Pandemics, Protests, and Panic Attacks: A History Defined by Tragedy There is an age-old story that illustrates the state of millions of American teens today. It’s the tale of a man who sat in a local diner waiting for his lunch. His countenance was down, he was feeling discouraged, and his tone was melancholy. When his waitress saw he was feeling low, she immediately suggested he go see Grimaldi. The circus was in town, and Grimaldi was a clown who made everyone laugh. The waitress was certain Grimaldi could cheer up her sad customer. Little did she know with whom she was speaking. The man looked up at her and replied, “But, ma’am. I am Grimaldi.” In many ways, this is a picture of the Pandemic Population. On the outside, they’re clowning around on Snapchat and TikTok, laughing at memes and making others laugh at filtered photos on social media. Inside, however, their mental health has gone south. It appears their life is a comedy, but in reality, it feels like a tragedy. -

Alone Together: Exploring Community on an Incel Forum

Alone Together: Exploring Community on an Incel Forum by Vanja Zdjelar B.A. (Hons., Criminology), Simon Fraser University, 2016 B.A. (Political Science and Communication), Simon Fraser University, 2016 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Criminology Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Vanja Zdjelar 2020 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY FALL 2020 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Declaration of Committee Name: Vanja Zdjelar Degree: Master of Arts Thesis title: Alone Together: Exploring Community on an Incel Forum Committee: Chair: Bryan Kinney Associate Professor, Criminology Garth Davies Supervisor Associate Professor, Criminology Sheri Fabian Committee Member University Lecturer, Criminology David Hofmann Examiner Associate Professor, Sociology University of New Brunswick ii Abstract Incels, or involuntary celibates, are men who are angry and frustrated at their inability to find sexual or intimate partners. This anger has repeatedly resulted in violence against women. Because incels are a relatively new phenomenon, there are many gaps in our knowledge, including how, and to what extent, incel forums function as online communities. The current study begins to fill this lacuna by qualitatively analyzing the incels.co forum to understand how community is created through online discourse. Both inductive and deductive thematic analyses were conducted on 17 threads (3400 posts). The results confirm that the incels.co forum functions as a community. Four themes in relation to community were found: The incel brotherhood; We can disagree, but you’re wrong; We are all coping here; and Will the real incel come forward. -

Alexander B. Stohler Modern American Hategroups: Lndoctrination Through Bigotry, Music, Yiolence & the Internet

Alexander B. Stohler Modern American Hategroups: lndoctrination Through Bigotry, Music, Yiolence & the Internet Alexander B. Stohler FacultyAdviser: Dr, Dennis Klein r'^dw May 13,2020 )ol, Masters of Arts in Holocaust & Genocide Studies Kean University In partialfulfillumt of the rcquirementfar the degee of Moster of A* Abstract: I focused my research on modern, American hate groups. I found some criteria for early- warning signs of antisemitic, bigoted and genocidal activities. I included a summary of neo-Nazi and white supremacy groups in modern American and then moved to a more specific focus on contemporary and prominent groups like Atomwaffen Division, the Proud Boys, the Vinlanders Social Club, the Base, Rise Against Movement, the Hammerskins, and other prominent antisemitic and hate-driven groups. Trends of hate-speech, acts of vandalism and acts of violence within the past fifty years were examined. Also, how law enforcement and the legal system has responded to these activities has been included as well. The different methods these groups use for indoctrination of younger generations has been an important aspect of my research: the consistent use of hate-rock and how hate-groups have co-opted punk and hardcore music to further their ideology. Live-music concerts and festivals surrounding these types of bands and how hate-groups have used music as a means to fund their more violent activities have been crucial components of my research as well. The use of other forms of music and the reactions of non-hate-based artists are also included. The use of the internet, social media and other digital means has also be a primary point of discussion. -

Reverse-Engineering Twitter's Content Removal

“We Believe in Free Expression...” Reverse-Engineering Twitter’s Content Removal Policies for the Alt-Right The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:38811534 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Contents The Problem & The Motivation .............................................................................. 4 Free Speech: Before and After the Internet ......................................................... 5 Speech on Twitter .............................................................................................. 11 Defining the Alt-Right ....................................................................................... 13 The Alt-Right on Social Media ......................................................................... 14 Social Media Reaction to Charlottesville .......................................................... 17 Twitter’s Policies for the Alt-Right ................................................................... 19 Previous Work ................................................................................................... 21 Structure of this Thesis ..................................................................................... -

Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and Its Multifarious Enemies

Angles New Perspectives on the Anglophone World 10 | 2020 Creating the Enemy The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies Maxime Dafaure Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/angles/369 ISSN: 2274-2042 Publisher Société des Anglicistes de l'Enseignement Supérieur Electronic reference Maxime Dafaure, « The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies », Angles [Online], 10 | 2020, Online since 01 April 2020, connection on 28 July 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/angles/369 This text was automatically generated on 28 July 2020. Angles. New Perspectives on the Anglophone World is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies 1 The “Great Meme War:” the Alt- Right and its Multifarious Enemies Maxime Dafaure Memes and the metapolitics of the alt-right 1 The alt-right has been a major actor of the online culture wars of the past few years. Since it came to prominence during the 2014 Gamergate controversy,1 this loosely- defined, puzzling movement has achieved mainstream recognition and has been the subject of discussion by journalists and scholars alike. Although the movement is notoriously difficult to define, a few overarching themes can be delineated: unequivocal rejections of immigration and multiculturalism among most, if not all, alt- right subgroups; an intense criticism of feminism, in particular within the manosphere community, which itself is divided into several clans with different goals and subcultures (men’s rights activists, Men Going Their Own Way, pick-up artists, incels).2 Demographically speaking, an overwhelming majority of alt-righters are white heterosexual males, one of the major social categories who feel dispossessed and resentful, as pointed out as early as in the mid-20th century by Daniel Bell, and more recently by Michael Kimmel (Angry White Men 2013) and Dick Howard (Les Ombres de l’Amérique 2017). -

Qanon and Facebook

The Boom Before the Ban: QAnon and Facebook Ciaran O’Connor, Cooper Gatewood, Kendrick McDonald and Sarah Brandt 2 ‘THE GREAT REPLACEMENT’: THE VIOLENT CONSEQUENCES OF MAINSTREAMED EXTREMISM / Document title: About this report About NewsGuard This report is a collaboration between the Institute Launched in March 2018 by media entrepreneur and for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) and the nonpartisan award-winning journalist Steven Brill and former Wall news-rating organisation NewsGuard. It analyses Street Journal publisher Gordon Crovitz, NewsGuard QAnon-related contents on Facebook during a provides credibility ratings and detailed “Nutrition period of increased activity, just before the platform Labels” for thousands of news and information websites. implemented moderation of public contents spreading NewsGuard rates all the news and information websites the conspiracy theory. Combining quantitative and that account for 95% of online engagement across the qualitative analysis, this report looks at key trends in US, UK, Germany, France, and Italy. NewsGuard products discussions around QAnon, prominent accounts in that include NewsGuard, HealthGuard, and BrandGuard, discussion, and domains – particularly news websites which helps marketers concerned about their brand – that were frequently shared alongside QAnon safety, and the Misinformation Fingerprints catalogue of contents on Facebook. This report also recommends top hoaxes. some steps to be taken by technology companies, governments and the media when seeking to counter NewsGuard rates each site based on nine apolitical the spread of problematic conspiracy theories like criteria of journalistic practice, including whether a QAnon on social media. site repeatedly publishes false content, whether it regularly corrects or clarifies errors, and whether it avoids deceptive headlines. -

Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right

Maik Fielitz, Nick Thurston (eds.) Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right Political Science | Volume 71 Maik Fielitz, Nick Thurston (eds.) Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right Online Actions and Offline Consequences in Europe and the US With kind support of Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No- Derivatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commer- cial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for com- mercial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contacting [email protected] Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. The obligation to research and clear permission lies solely with the party re-using the material. © 2019 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Cover layout: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Typeset by Alexander Masch, Bielefeld Printed by Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-4670-2 PDF-ISBN 978-3-8394-4670-6 https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839446706 Contents Introduction | 7 Stephen Albrecht, Maik Fielitz and Nick Thurston ANALYZING Understanding the Alt-Right. -

ENGL 762 Syllabus Hate

ENGL 762 1 THE LITERATURE OF HATE English 762 Tuesday: 2:00-4:50 / 309 Bingham Instructor: Danielle Christmas Office Hours: Thursday 3-4:30 Office: 411 Greenlaw Hall (confirm by email) E-mail: [email protected] Section: 001 Course Description: The social and political tenor of the moment has brought the normalization of white nationalist rhetoric into relief. However, Americans have always found creative ways to express a desire to exclude or eradicate the racial other. In this graduate seminar, students will look at the arc of fiction narratives that have inspired and defined contemporary hate movements in the United States. Starting with Thomas Dixon’s neo-Confederate romance The Clansman (1905), we will move through the foundational texts of white nationalism today, including Jean Raspail’s refugee apocalypse The Camp of the Saints (1973), William Pierce’s race-war account The Turner Diaries (1978), and globalization dystopias like Ward Kendall’s Hold Back This Day (2001). We will also discuss those mainstream works that have been adopted into the white nationalist canon, including Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice (1813) and Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho (1991). Finally, our discussion will be contextualized using social critiques like J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy (2016) and Vegas Tenold’s Everything You Love Will Burn (2018). By the end of the semester, students will have the capacity to understand the place of this literary subculture within the larger body of contemporary American cultural production and the urgent discourses of race and violence that animate it. Students should have a high tolerance for disturbing content and a spirit of critical curiosity. -

Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online Alice Marwick and Rebecca Lewis CONTENTS

Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online Alice Marwick and Rebecca Lewis CONTENTS Executive Summary ....................................................... 1 What Techniques Do Media Manipulators Use? ....... 33 Understanding Media Manipulation ............................ 2 Participatory Culture ........................................... 33 Who is Manipulating the Media? ................................. 4 Networks ............................................................. 34 Internet Trolls ......................................................... 4 Memes ................................................................. 35 Gamergaters .......................................................... 7 Bots ...................................................................... 36 Hate Groups and Ideologues ............................... 9 Strategic Amplification and Framing ................. 38 The Alt-Right ................................................... 9 Why is the Media Vulnerable? .................................... 40 The Manosphere .......................................... 13 Lack of Trust in Media ......................................... 40 Conspiracy Theorists ........................................... 17 Decline of Local News ........................................ 41 Influencers............................................................ 20 The Attention Economy ...................................... 42 Hyper-Partisan News Outlets ............................. 21 What are the Outcomes? .......................................... -

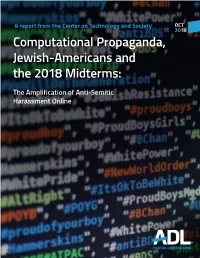

Computational Propaganda, Jewish-Americans and the 2018 Midterms

A report from the Center on Technology and Society OCT 2018 Computational Propaganda, Jewish-Americans and the 2018 Midterms: The Amplification of Anti-Semitic Harassment Online Our Mission: To stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment to all. ABOUT CENTER FOR TECHNOLOGY & SOCIETY AND THE BELFER FELLOWS In a world riddled with cyberhate, online harassment, and misuses of technology, the Center for Technology & Society (CTS) serves as a resource to tech platforms and develops proactive solutions. Launched in 2017 and headquartered in Silicon Valley, CTS aims for global impacts and applications in an increasingly borderless space. It is a force for innovation, producing cutting-edge research to enable online civility, protect vulnerable populations, support digital citizenship, and engage youth. CTS builds on ADL’s century of experience building a world without hate and supplies the tools to make that a possibility both online and off-line. The Belfer Fellowship program supports CTS’s efforts to create innovative solutions to counter online hate and ensure justice and fair treatment for all in the digital age through fellowships in research and outreach projects. The program is made possible by a generous contribution from the Robert A. and Renée E. Belfer Family Foundation. The inaugural 2018-2019 Fellows are: • Rev. Dr. Patricia Novick, Ph.D., of the Multicultural Leadership Academy, Samuel Woolley is the research a program that brings Latino and African-American leaders together. director of the Digital Intelligence (DigIntel) Lab at IFTF, a research • Dr. Karen Schrier, an associate professor at Marist College and its associate at the Oxford Internet founding director of the Games and Emerging Media Program.