The Spread of Torres Strait Creole to the Central Islands Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sociality and Locality in a Torres Strait Community

Past Visions, Present Lives: sociality and locality in a Torres Strait community. Thesis submitted by Julie Lahn BA (Hons) (JCU) November 2003 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Anthropology, Archaeology and Sociology Faculty of Arts, Education and Social Sciences James Cook University Statement of Access I, the undersigned, the author of this thesis, understand that James Cook University will make it available for use within the University Library and, by microfilm or other means, allow access to users in other approved libraries. All users consulting this thesis will have to sign the following statement: In consulting this thesis I agree not to copy or closely paraphrase it in whole or in part without the written consent of the author; and to make proper public written acknowledgment for any assistance that I have obtained from it. Beyond this, I do not wish to place any restriction on access to this thesis. _________________________________ __________ Signature Date ii Statement of Sources Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text and a list of references is given. ____________________________________ ____________________ Signature Date iii Acknowledgments My main period of fieldwork was conducted over fifteen months at Warraber Island between July 1996 and September 1997. I am grateful to many Warraberans for their assistance and generosity both during my main fieldwork and subsequent visits to the island. -

EALD Information (PDF, 434

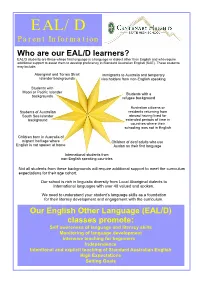

EAL/D Parent Information Who are our EAL/D learners? EAL/D students are those whose first language is a language or dialect other than English and who require additional support to assist them to develop proficiency in Standard Australian English (SAE). These students may include: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Immigrants to Australia and temporary Islander backgrounds visa holders from non-English speaking Students with Maori or Pacific Islander Students with a backgrounds refugee background Australian citizens or Students of Australian residents returning from South Sea islander abroad having lived for background extended periods of time in countries where their schooling was not in English Children born in Australia of migrant heritage where Children of deaf adults who use English is not spoken at home Auslan as their first language International students from non-English speaking countries Not all students from these backgrounds will require additional support to meet the curriculum expectations for their age cohort. Our school is rich in linguistic diversity from Local Aboriginal dialects to International languages with over 40 valued and spoken. We need to understand your student’s language skills as a foundation for their literacy development and engagement with the curriculum. Our English Other Language (EAL/D) classes promote: Self awareness of language and literacy skills Monitoring of language development Intensive teaching for beginners Independence Intentional and explicit teaching of Standard Australian English High Expectations Setting Goals When schools know students speak other languages they can support students in engaging in their learning to reach their educational potential. The information on these questions allows for the right support for your student. -

Guide to Sound Recordings Collected by Margaret Elizabeth Lawrie, 1965

Interim Finding aid LAWRIE_M02 Sound recordings collected by Margaret Elizabeth Lawrie, 1965-1967 Prepared March 2013 by SL Last updated 23 December 2016 ACCESS Availability of copies Listening copies are available. Contact the AIATSIS Audiovisual Access Unit by completing an online enquiry form or phone (02) 6261 4212 to arrange an appointment to listen to the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on listening This collection is open for listening. Restrictions on use Copies of this collection may be made for private research. Permission must be sought from the State Library of Queensland as well as the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community for any publication or quotation of this material. Any publication or quotation must be consistent with the Copyright Act (1968). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1965-1967 Extent: 55 sound tape reels (ca. 53 hrs. 15 min.) : analogue, 1 7/8-3 3/4 ips, stereo, mono + field tape report sheets. Production history These recordings were collected by Margaret Lawrie between 1965 and 1967 during fieldwork at Saibai, Boigu, Dauan, Mabuiag, Badu, Kubin, Iama, Erub, Mer, Poruma, Waraber, Masig, Ugar and Waiben in the Torres Strait, and Bamaga and Pormpuraaw, Cape York, Queensland. The purpose of the field trips was to document the stories, songs and languages of the people of the Torres Strait. Speakers and performers include Nawia Elu, George Passi, Alfred Aniba, Kadam Waigana, Marypa Waigana, Enosa Waigana, Aniba Asa, Madi Ano, Wake Obar, Wagia Waia, Timothy (Susui) Akiba, Mebai Warusam, Kala -

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island). -

Round 232021

FRONTTHE ROW ROUND 23 2021 VOLUME 2 · ISSUE 24 PARTY AT THE BACK Backs and halves dominate the Run rabbit run rookie class of 2021 TheBiggestTiger zones in on a South Sydney superstar! INSIDE: ROUND 23 PROGRAM - SQUAD LISTS, PREVIEWS & HEAD TO HEAD STATS, R22 REVIEWED LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM AUSTRALIA’S LEADING INDEPENDENT RUGBY LEAGUE WEBSITE THERE IS NO OFF-SEASON 2 | LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM | THE FRONT ROW | VOL 2 ISSUE 24 What’s inside From the editor THE FRONT ROW - VOL 2 ISSUE 24 Tim Costello From the editor 3 It's been an interesting year for break-out stars. Were painfully aware of the lack of lower-grade rugby league that's been able Feature Rookie Class of 2021 4-5 to be played in the last 18 months, and the impact that's going to have on development pathways in all states - particularly in History Tommy Anderson 6-7 New South Wales. The results seems to be that we're getting a lot more athletic, backline-suited players coming through, with Feature The Run Home 8 new battle-hardened forwards making the grade few and far between. Over the page Rob Crosby highlights the Rookie Class Feature 'Trell' 9 of 2021 - well worth a read. NRL Ladder, Stats Leaders 10 Also this week thanks to Andrew Ferguson, we have a footy history piece on Tommy Anderson - an inaugural South Sydney GAME DAY · NRL Round 23 11-27 player who was 'never the same' after facing off against Dally Messenger. The BiggestTiger's weekly illustration shows off the LU Team Tips 11 speed and skill of Latrell Mitchell, and we update the run home to the finals with just three games left til the September action THU Gold Coast v Melbourne 12-13 kicks off. -

GRAND, DADDY Thurston and the Cowboys Cap a Sensational Year for Queensland

Official Magazine of Queensland’s Former Origin Greats MAGAZINEEDITION 26 SUMMER 2015 GRAND, DADDY Thurston and the Cowboys cap a sensational year for Queensland Picture: News Queensland A MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE CHAIRMAN AT this time of the year, we are Sims and Edrick Lee is what will help home on Castlemaine Street around the normally thinking of all the fanciful deliver us many more celebrations in time of the 2016 Origin series. things we want to put onto our the years to come. It was the dream of our founder, the Christmas wishlist. Not all of those guys played Origin great Dick “Tosser” Turner, that the But it is hard to imagine rugby league this year, but they all continued their FOGS would one day have their own fans in Queensland could ask for much education in the Queensland system to premises, and the fact we now have it is more than what was delivered in an ensure they will be ready when they are one of the great successes we can incredible 2015 season. called on in the next year or so. celebrate as an organisation. Our ninth State of Origin series win Planning for the future has been a While we have been very happy in 10 years, a record-breaking win huge part of Queensland’s success over during our time at Suncorp Stadium, over the Blues in Game 3, the first the past decade, and it is what will that we are now so close to moving into all-Queensland grand final between ensure more success in the future. -

Health and Physical Education

Resource Guide Health and Physical Education The information and resources contained in this guide provide a platform for teachers and educators to consider how to effectively embed important ideas around reconciliation, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories, cultures and contributions, within the specific subject/learning area of Health and Physical Education. Please note that this guide is neither prescriptive nor exhaustive, and that users are encouraged to consult with their local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community, and critically evaluate resources, in engaging with the material contained in the guide. Page 2: Background and Introduction to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Page 3: Timeline of Key Dates in the more Contemporary History of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Page 5: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Organisations, Programs and Campaigns Page 6: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Sportspeople Page 8: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Events/Celebrations Page 12: Other Online Guides/Reference Materials Page 14: Reflective Questions for Health and Physical Education Staff and Students Please be aware this guide may contain references to names and works of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people that are now deceased. External links may also include names and images of those who are now deceased. Page | 1 Background and Introduction to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education “[Health and] healing goes beyond treating…disease. It is about working towards reclaiming a sense of balance and harmony in the physical, psychological, social, cultural and spiritual works of our people, and practicing our profession in a manner that upholds these multiple dimension of Indigenous health” –Professor Helen Milroy, Aboriginal Child Psychiatrist and Australia’s first Aboriginal medical Doctor. -

Interweaving Oral and Written Sources in Compiling Torres Strait Islander Genealogies

Oral History Australia Journal No. 41, 2019, 87–97 Necessary but not Suffcient: Interweaving Oral and Written Sources in Compiling Torres Strait Islander Genealogies Anna Shnukal under which the information was recorded; by whom 1 Introduction and for what purpose information was recorded; the Despite their defciencies, Torres Strait Islander informant’s relationship with the named individual. genealogies are relevant to oral, family and local The defects of oral sources include unreliable or even historians, linguists, anthropologists, archaeologists contradictory memories, generational confation, the and native title practitioners.Kinship and the creation of use of alternative names for an individual and gaps individual and family connections (‘roads’) which are in the early genealogical record (for reasons outlined orally transmitted over the generations are fundamental below). to Islander culture and society. It is only through In 1980 I was awarded a post-doctoral sociolinguistic detailed genealogical research that the relationships research fellowship by the Australian Institute of between individuals, families, clans and place in Torres Aboriginal Studies (today AIATSIS). I was to devise Strait can be discerned. These relationships continue to a spelling system, grammar and dictionary for the infuence the history of the region and, more generally, regional lingua franca – now called Torres Strait Australia. Creole or Yumpla Tok – and document its history. I Although Islanders began to record genealogical subsequently compiled over 1200 searchable family information in notebooks and family bibles from the databases from the 1830s to the early 1940s (and, 1870s, the academic study of Islander genealogies in some cases, beyond). Describing this unwritten began with W.H.R. -

Issues in the Maintenance of Aboriginal Languages and Aboriginal English

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 378 829 FL 022 748 AUTHOR Malcolm, Ian G. TITLE Issues in the Maintenance of Aboriginal Languages and Aboriginal English. PUB DATE Oct 94 NOTE 19p.; Paper presented at the Annual National Languages Conference of the Australian Federation of Modern Language Teachers' Associations (10th Perth, Western Australia, Australia, October 1-4, 1994). PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.)(120) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PCO1 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Bilingual Education; *English; Foreign Countries; *Indigenous Populations; *Language Maintenance; *Language Planning; Language Variation; *Native Language Instruction; Program Descriptions; Public Policy; *Regional Dialects; Standard Spoken Usage IDENTIFIERS *Australia; Edith Ccwan University (Australia) ABSTRACT Activities at Edith Cowan University (Australia) in support of the maintenance of Aboriginal languages and Aboriginal English are discussed. Discussion begins withan examination of the concept of language maintenance and the reasons it merits the attention of linguists, language planners, and language teachers. Australian policy concerning maintenance of Aboriginal languages is briefly outlined. Research on language maintenance and langyage shift in relation to endangered languages is also reviewed, and the ambiguous role of education in language maintenance is considered. Two areas in which Edith Cowan University has been activeare then described. The first is a pilot study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander language development and maintenance needs and activities,a national initiative with its origins in national language and literacy policy. The second is an effort to mobilize teachers for bidialectal education, in both Aboriginal English and stand,Ardspoken English. The project involves the training of 20 volunteer teachers of Aboriginal children. The role of the university in facilitating change and supporting language maintenance is emphasized. -

Print ED356648.TIF

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 356 648 FL 021 143 AUTHOR Lo Bianco, Joseph, Ed. TITLE VOX: The Journal of the Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education (AACLAME). 1989-1991. INSTITUTION Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education, Canberra. REPORT NO ISSN-1032-0458 PUS DATE 91 NOTE 332p.; Intended to be published twice per year. Two-cone charts and colored photographs may not reproduce well. PUS TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT VOX: The Journal of the Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education; n3-5 1989-1991 EDRS PRICE MfO1 /PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Asian Studies; Bilingual Education; Certification; Communicative Competence (Languages); Comparative Education; Diachronic Linguistics; English (Second Language); Ethnic Groups; Foreign Countries; French; Immersion Programs; Immigrants; Indigenous Populations; Interpretive Skills; Italian; *Language Maintenance; *Language Role; Languages for Special Purposes: Language Tests; Language Variation; *Literacy; Minority Groups; Multicultural Education; Native Language Instruction; Pidgins; Second Language Instruction; Second Language Programs; *Second Languages; Sex; Skill Development; Student Attitudes; Testing IDENTIFIERS Africa; *Australia; Japan; Maori (People); Melanesia; Netherlands; New Zealand; Singapore; Spain ABSTRACT This document consists of the three issues of the aerial "VOX" published in 1989-1991. Major articles in these issues include: "The Original Languages of Australia"; "UNESCO and Universal -

Queensland Rugby Football League Limited Notice of General Meeting 2 Directors 2 Directors’ Meetings 3 Chairman’S Report 2011 4

2011 queensland rugby football league limited Notice of General Meeting 2 Directors 2 Directors’ Meetings 3 Chairman’s Report 2011 4 Rebuilding Rugby League Campaign 6 Ross Livermore 7 Tribute to Queensland Representatives 8 Major Sponsors 9 ARL Commission 10 Valé Arthur Beetson 11 Valé Des Webb 12 State Government Support 13 Volunteer Awards 13 Queensland Sport Awards 13 ASADA Testing Program 14 QRL Website 14 Maroon Members 14 QRL History Committee 16 QRL Referees’ Board 17 QRL Juniors’ Board 18 Education & Development 20 Murri Carnival 21 Women & Girls 23 Contents ARL Development 24 Harvey Norman State of Origin Series 26 XXXX Queensland Maroons State of Origin Team 28 Maroon Kangaroos 30 Queensland Academy of Sport 31 Intrust Super Cup 32 Historic Cup Match in Bamaga 34 XXXX Queensland Residents 36 XXXX Queensland Rangers 37 Queensland Under 18s 38 Under 18 Maroons 39 Queensland Under 16s 40 Under 16 Maroons 41 Queensland Women’s Team 42 Cyril Connell & Mal Meninga Cups 43 A Grade Carnival 44 Outback Matches 44 Schools 45 Brisbane Broncos 46 North Queensland Cowboys 47 Gold Coast Titans 47 Statistics 2011 47 2011 Senior Premiers 49 Conclusion 49 Financials 50 Declarations 52 Directors’ Declaration 53 Auditors’ Independence Declaration 53 Independent Auditors’ Report 54 Statement of Comprehensive Income 55 Balance Sheet 56 Statement of Changes in Equity 57 Statement of Cash Flows 57 Notes to the Financial Statements 58 1 NOTICe of general meeting direCTORS’ meetings Notice is hereby given that the Annual 2. To appoint the Directors for the 2012 year. NUMBER OF MEETINGS NUMBER OF MEETINGS DIRECTOR General Meeting of the Queensland Rugby 3. -

Natural and Cultural Histories of the Island of Mabuyag, Torres Strait. Edited by Ian J

Memoirs of the Queensland Museum | Culture Volume 8 Part 1 Goemulgaw Lagal: Natural and Cultural Histories of the Island of Mabuyag, Torres Strait. Edited by Ian J. McNiven and Garrick Hitchcock Minister: Annastacia Palaszczuk MP, Premier and Minister for the Arts CEO: Suzanne Miller, BSc(Hons), PhD, FGS, FMinSoc, FAIMM, FGSA , FRSSA Editor in Chief: J.N.A. Hooper, PhD Editors: Ian J. McNiven PhD and Garrick Hitchcock, BA (Hons) PhD(QLD) FLS FRGS Issue Editors: Geraldine Mate, PhD PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD 2015 © Queensland Museum PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone: +61 (0) 7 3840 7555 Fax: +61 (0) 7 3846 1226 Web: qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 VOLUME 8 IS COMPLETE IN 2 PARTS COVER Image on book cover: People tending to a ground oven (umai) at Nayedh, Bau village, Mabuyag, 1921. Photographed by Frank Hurley (National Library of Australia: pic-vn3314129-v). NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the CEO. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed on the Queensland Museum website qm.qld.gov.au A Queensland Government Project Design and Layout: Tanya Edbrooke, Queensland Museum Printed by Watson, Ferguson & Company ‘Sweet sounds of this place’: contemporary recordings and socio-cultural uses of Mabuyag music Karl NEUENFELDT Neuenfeldt, K.