Darnley Island), Torres Strait

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sociality and Locality in a Torres Strait Community

Past Visions, Present Lives: sociality and locality in a Torres Strait community. Thesis submitted by Julie Lahn BA (Hons) (JCU) November 2003 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Anthropology, Archaeology and Sociology Faculty of Arts, Education and Social Sciences James Cook University Statement of Access I, the undersigned, the author of this thesis, understand that James Cook University will make it available for use within the University Library and, by microfilm or other means, allow access to users in other approved libraries. All users consulting this thesis will have to sign the following statement: In consulting this thesis I agree not to copy or closely paraphrase it in whole or in part without the written consent of the author; and to make proper public written acknowledgment for any assistance that I have obtained from it. Beyond this, I do not wish to place any restriction on access to this thesis. _________________________________ __________ Signature Date ii Statement of Sources Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text and a list of references is given. ____________________________________ ____________________ Signature Date iii Acknowledgments My main period of fieldwork was conducted over fifteen months at Warraber Island between July 1996 and September 1997. I am grateful to many Warraberans for their assistance and generosity both during my main fieldwork and subsequent visits to the island. -

EALD Information (PDF, 434

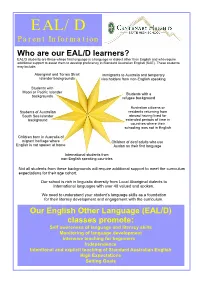

EAL/D Parent Information Who are our EAL/D learners? EAL/D students are those whose first language is a language or dialect other than English and who require additional support to assist them to develop proficiency in Standard Australian English (SAE). These students may include: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Immigrants to Australia and temporary Islander backgrounds visa holders from non-English speaking Students with Maori or Pacific Islander Students with a backgrounds refugee background Australian citizens or Students of Australian residents returning from South Sea islander abroad having lived for background extended periods of time in countries where their schooling was not in English Children born in Australia of migrant heritage where Children of deaf adults who use English is not spoken at home Auslan as their first language International students from non-English speaking countries Not all students from these backgrounds will require additional support to meet the curriculum expectations for their age cohort. Our school is rich in linguistic diversity from Local Aboriginal dialects to International languages with over 40 valued and spoken. We need to understand your student’s language skills as a foundation for their literacy development and engagement with the curriculum. Our English Other Language (EAL/D) classes promote: Self awareness of language and literacy skills Monitoring of language development Intensive teaching for beginners Independence Intentional and explicit teaching of Standard Australian English High Expectations Setting Goals When schools know students speak other languages they can support students in engaging in their learning to reach their educational potential. The information on these questions allows for the right support for your student. -

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island). -

The Spread of Torres Strait Creole to the Central Islands Of

THE SPREAD OF TORRES STRAIT CREOLE TO THE CENTRAL ISLANDS OF TORRES STRAIT Anna Shnukal INTRODUCTION1 The following paper outlines the second stage of development of Torres Strait Creole, now the lingua franca, or common language, of Torres Strait Islanders everywhere.2 The first stage, which I discussed in an earlier volume of this journal, was that of the creolisation of Pacific Pidgin English around the turn of the century in three Torres Strait island commu nities.3 In that article, I argued that creolisation was the result of two factors not reproduced elsewhere in Torres Strait at the time: (1) the creation of de facto Pacific Islander settle ments on Erub, Ugar and St Paul’s Anglican Mission, Moa, where the Pacific Islanders out numbered Torres Strait Islanders and (2) the integration into those communities of these hitherto marginal immigrants. The prestige of the Pacific Islanders derived from their func tion as linguistic and cultural middlemen, interpreters of European ways of life to their Torres Strait Islander kinfolk. A third stage in the development of the creole began with the war years, when almost all able-bodied men left their home islands to join the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion and, for the first time, came into daily contact with English-speaking Europeans. The present overview article traces the diffusion of Pacific Pidgin English and the creole which developed from it, focusing on the central islands of the Strait between the early 1900s and the beginning of World War II. Also briefly discussed are certain interwoven historical Anna Shnukal carried out research into Torres Strait Creole while a Visiting Research Fellow in Socio linguistics at the Australian Institute o f Aboriginal Studies. -

Issues in the Maintenance of Aboriginal Languages and Aboriginal English

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 378 829 FL 022 748 AUTHOR Malcolm, Ian G. TITLE Issues in the Maintenance of Aboriginal Languages and Aboriginal English. PUB DATE Oct 94 NOTE 19p.; Paper presented at the Annual National Languages Conference of the Australian Federation of Modern Language Teachers' Associations (10th Perth, Western Australia, Australia, October 1-4, 1994). PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.)(120) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PCO1 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Bilingual Education; *English; Foreign Countries; *Indigenous Populations; *Language Maintenance; *Language Planning; Language Variation; *Native Language Instruction; Program Descriptions; Public Policy; *Regional Dialects; Standard Spoken Usage IDENTIFIERS *Australia; Edith Ccwan University (Australia) ABSTRACT Activities at Edith Cowan University (Australia) in support of the maintenance of Aboriginal languages and Aboriginal English are discussed. Discussion begins withan examination of the concept of language maintenance and the reasons it merits the attention of linguists, language planners, and language teachers. Australian policy concerning maintenance of Aboriginal languages is briefly outlined. Research on language maintenance and langyage shift in relation to endangered languages is also reviewed, and the ambiguous role of education in language maintenance is considered. Two areas in which Edith Cowan University has been activeare then described. The first is a pilot study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander language development and maintenance needs and activities,a national initiative with its origins in national language and literacy policy. The second is an effort to mobilize teachers for bidialectal education, in both Aboriginal English and stand,Ardspoken English. The project involves the training of 20 volunteer teachers of Aboriginal children. The role of the university in facilitating change and supporting language maintenance is emphasized. -

Print ED356648.TIF

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 356 648 FL 021 143 AUTHOR Lo Bianco, Joseph, Ed. TITLE VOX: The Journal of the Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education (AACLAME). 1989-1991. INSTITUTION Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education, Canberra. REPORT NO ISSN-1032-0458 PUS DATE 91 NOTE 332p.; Intended to be published twice per year. Two-cone charts and colored photographs may not reproduce well. PUS TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT VOX: The Journal of the Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education; n3-5 1989-1991 EDRS PRICE MfO1 /PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Asian Studies; Bilingual Education; Certification; Communicative Competence (Languages); Comparative Education; Diachronic Linguistics; English (Second Language); Ethnic Groups; Foreign Countries; French; Immersion Programs; Immigrants; Indigenous Populations; Interpretive Skills; Italian; *Language Maintenance; *Language Role; Languages for Special Purposes: Language Tests; Language Variation; *Literacy; Minority Groups; Multicultural Education; Native Language Instruction; Pidgins; Second Language Instruction; Second Language Programs; *Second Languages; Sex; Skill Development; Student Attitudes; Testing IDENTIFIERS Africa; *Australia; Japan; Maori (People); Melanesia; Netherlands; New Zealand; Singapore; Spain ABSTRACT This document consists of the three issues of the aerial "VOX" published in 1989-1991. Major articles in these issues include: "The Original Languages of Australia"; "UNESCO and Universal -

Natural and Cultural Histories of the Island of Mabuyag, Torres Strait. Edited by Ian J

Memoirs of the Queensland Museum | Culture Volume 8 Part 1 Goemulgaw Lagal: Natural and Cultural Histories of the Island of Mabuyag, Torres Strait. Edited by Ian J. McNiven and Garrick Hitchcock Minister: Annastacia Palaszczuk MP, Premier and Minister for the Arts CEO: Suzanne Miller, BSc(Hons), PhD, FGS, FMinSoc, FAIMM, FGSA , FRSSA Editor in Chief: J.N.A. Hooper, PhD Editors: Ian J. McNiven PhD and Garrick Hitchcock, BA (Hons) PhD(QLD) FLS FRGS Issue Editors: Geraldine Mate, PhD PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD 2015 © Queensland Museum PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone: +61 (0) 7 3840 7555 Fax: +61 (0) 7 3846 1226 Web: qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 VOLUME 8 IS COMPLETE IN 2 PARTS COVER Image on book cover: People tending to a ground oven (umai) at Nayedh, Bau village, Mabuyag, 1921. Photographed by Frank Hurley (National Library of Australia: pic-vn3314129-v). NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the CEO. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed on the Queensland Museum website qm.qld.gov.au A Queensland Government Project Design and Layout: Tanya Edbrooke, Queensland Museum Printed by Watson, Ferguson & Company ‘Sweet sounds of this place’: contemporary recordings and socio-cultural uses of Mabuyag music Karl NEUENFELDT Neuenfeldt, K. -

Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo

Oceania No. Language [ISO 639-3 Code] Country (Region) 1 ’Are’are [alu] Iouo Solomon Islands 2 ’Auhelawa [kud] Iouo Papua New Guinea 3 Abadi [kbt] Iouo Papua New Guinea 4 Abaga [abg] Iouo Papua New Guinea 5 Abau [aau] Iouo Papua New Guinea 6 Abom [aob] Iouo Papua New Guinea 7 Abu [ado] Iouo Papua New Guinea 8 Adnyamathanha [adt] Iouo Australia 9 Adzera [adz] Iouo Papua New Guinea 10 Aeka [aez] Iouo Papua New Guinea 11 Aekyom [awi] Iouo Papua New Guinea 12 Agarabi [agd] Iouo Papua New Guinea 13 Agi [aif] Iouo Papua New Guinea 14 Agob [kit] Iouo Papua New Guinea 15 Aighon [aix] Iouo Papua New Guinea 16 Aiklep [mwg] Iouo Papua New Guinea 17 Aimele [ail] Iouo Papua New Guinea 18 Ainbai [aic] Iouo Papua New Guinea 19 Aiome [aki] Iouo Papua New Guinea 20 Äiwoo [nfl] Iouo Solomon Islands 21 Ajië [aji] Iouo New Caledonia 22 Ak [akq] Iouo Papua New Guinea 23 Akei [tsr] Iouo Vanuatu 24 Akolet [akt] Iouo Papua New Guinea 25 Akoye [miw] Iouo Papua New Guinea 26 Akukem [spm] Iouo Papua New Guinea 27 Alamblak [amp] Iouo Papua New Guinea 28 Alawa [alh] Iouo Australia 29 Alekano [gah] Iouo Papua New Guinea 30 Alyawarr [aly] Iouo Australia 31 Ama [amm] Iouo Papua New Guinea 32 Amaimon [ali] Iouo Papua New Guinea 33 Amal [aad] Iouo Papua New Guinea 34 Amanab [amn] Iouo Papua New Guinea 35 Amara [aie] Iouo Papua New Guinea 36 Amba [utp] Iouo Solomon Islands 37 Ambae, East [omb] Iouo Vanuatu 38 Ambae, West [nnd] Iouo Vanuatu 39 Ambakich [aew] Iouo Papua New Guinea 40 Amblong [alm] Iouo Vanuatu 1 Oceania No. -

Invisibility of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Contact Languages in Education and Indigenous Language Contexts

ARTICLES c EVERYWHERE AND NOWHERE: INVISIBILITY OF ABORIGINAL AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER CONTACT LANGUAGES IN EDUCATION AND INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE CONTEXTS Juanita Sellwood James Cook University Juanita Sellwood is a lecturer in the School of Education, James Cook University in Cairns. Her family heritage links to Masig (Yorke Island) in the Torres Strait. Juanita is a co-author of the subject ‘Teaching English as a Second Language to Indigenous Students’, the first compulsory course in a teacher education degree in Queensland about second language pedagogy for Indigenous learners of English as a Second/Additional Language or Dialect (ESL/D or EAL/D). Juanita has experienced first hand the difficulties of navigating a schooling system that did not recognise her home language, Yumplatok, or that she was an ESL learner. This experience has influenced her teaching and research interests which include cultural diversity, effective teaching practices for Indigenous ESL/D learners and the language ecologies of Indigenous Australians. Denise Angelo Northern Indigenous Schooling Support Unit, Education Queensland Denise Angelo is an educator, language teacher and linguist who currently manages the innovative Language Perspectives team in the Indigenous Schooling Support Unit in Cairns. She works throughout Queensland, collaboratively developing resources and delivering training to increase school capacity to support the achievement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students who are learners of English as a Foreign/Second/Additional Language or Dialect (EFL, ESL/D, EAL/D). Denise has worked in the areas of maintaining and reviving traditional Aboriginal languages, Aboriginal interpreting and translating, researching contact language varieties and teaching approaches for Indigenous students with language backgrounds other than Standard Australian English. -

Indigenous Knowledge and Cultural Values of Hammerhead Sharks in Northern Australia

Indigenous knowledge and cultural values of hammerhead sharks in Northern Australia Karin Gerhardt Project A5 - Establishing the status of Australia’s hammerhead sharks 30 November 2018 Milestone 14, Research Plan v4 (2018) www.nespmarine.edu.au Image credit: Artwork by Safina Stewart, Mabuiag Island and Wuthathi Country, www.artbysafina.com.au Title: Hammerhead (Date: 2016) This powerful and majestic Hammerhead Shark swims healthy and free in the beautiful Torres Strait. The sea urchins are a reminder of the Torres Strait Islander people who are the custodians of its islands and waters. “It is significant to place the urchins with the hammerhead. Together they are saying, ‘Come, let us all come together, despite our differences, and look after our ocean brothers.’” – Safina Stewart Enquiries should be addressed to: Karin Gerhardt [email protected] Project Leader’s Distribution List Lesley Gidding-Reeve Department of the Environment and Energy, Biodiversity Conservation Division Ivan Lawler Department of the Environment and Energy, Biodiversity Conservation Division David Wachenfeld Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority Preferred Citation Gerhardt, K (2018). Indigenous knowledge and cultural values of hammerhead sharks in Northern Australia. Report to the National Environmental Science Program, Marine Biodiversity Hub. James Cook University. Copyright This report is licensed by the University of Tasmania for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Australia Licence. For licence conditions, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ -

Torres Strait Islanders by Anna Shnukal

Torres Strait Islanders by Anna Shnukal From: Brandle, Maximilian (ed.) Multilcutlural Queensland 2001: 100 years, 100 communities, A century of contributions, Brisbane, The State of Queensland (Department of Premier and Cabinet), 2001. Introduction Torres Strait Islanders are the second group of Indigenous Australians and a minority within a minority. Torres Strait, which lies between Cape York and Papua New Guinea, is legally part of Queensland. Its islands were annexed comparatively late: those within 60 nautical miles (97 kilometres) of the coast in 1872, the remainder in 1879. At annexation, the Islanders became British subjects and their islands became Crown lands. At Federation they became Australian citizens although until comparatively recently they were denied rights and benefits which their fellow Australians took for granted. Torres Strait Islanders are not mainland Aboriginal people who inhabit the islands of Torres Strait. They are a separate people in origin, history and way of life. From the waters of the Strait, where the Coral and Arafura Seas meet in one of the most fragile and intricate waterways in the world, rise hundreds of islands, islets, cays, reefs and sandbanks. All these are traditionally named, owned and used. No two islands are identical, each being shaped by its unique landscape, stories and history. In the past many more islands were inhabited. Islanders live today in 18 permanent communities on 17 islands although they continue to visit their traditionally owned islands for fishing, gardening, food collecting, camping and picnicking. The first European settlement was established at Somerset, Cape York, in 1863. It was removed to Port Kennedy on Waiben (Thursday Island) in 1877 and, since then, Thursday Island has been the administrative and commercial ‘capital’ of Torres Strait. -

A Bibliography of the Traditional Games of Torres Strait Islander Peoples

+ A Bibliography of the Traditional Games of Torres Strait Islander Peoples Ken Edwards Tim Edwards Authors Ken Edwards has studied health and physical education, environmental science and sports history. He has taught health and physical education at both primary and secondary school level and has been a Head of Health and Physical Education at various schools. Ken completed a Ph.D. through UQ and has been an academic at QUT and Bond University and is now an Associate Professor in Sport, Health and Physical Education at USQ (Springfield Campus). Ken has had involvement in many sports as a player, coach and administrator. Tim Edwards has qualifications in physiotherapy and medicine through UQ and is currently a Medical Registrar in Brisbane, Queensland. Tim is an accomplished sportsman in various sports. Tim was involved in a great deal of the compilation, recording of entries and organisation of the research information. The fan-shape and white feathers of the dhari or dhoeri headdress are symbolic of the Torres Strait and this is incorporated into the Torres Strait Island flag. A Bibliography of the Traditional Games of Torres Strait Islander Peoples by Ken Edwards and Tim Edwards Cover Illustration and other artwork by Aboriginal artist Maxine Zealey (of the Gurang Gurang people). Traditional Games Series Copyright © 2011 by Ken Edwards. Photocopying of this e-book for personal use is permitted and encouraged. ISBN: 978-0-9872359-1-6 Faculty of Education University of Southern Queensland (USQ) Toowoomba, Queensland Acknowledgements This bibliography has been produced to provide an awareness of play cultures undertaken by Torres Strait Islander peoples and to encourage further study of these as part of an understanding of the sporting heritage of Australia.