Indigenous Knowledge and Cultural Values of Hammerhead Sharks in Northern Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sociality and Locality in a Torres Strait Community

Past Visions, Present Lives: sociality and locality in a Torres Strait community. Thesis submitted by Julie Lahn BA (Hons) (JCU) November 2003 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Anthropology, Archaeology and Sociology Faculty of Arts, Education and Social Sciences James Cook University Statement of Access I, the undersigned, the author of this thesis, understand that James Cook University will make it available for use within the University Library and, by microfilm or other means, allow access to users in other approved libraries. All users consulting this thesis will have to sign the following statement: In consulting this thesis I agree not to copy or closely paraphrase it in whole or in part without the written consent of the author; and to make proper public written acknowledgment for any assistance that I have obtained from it. Beyond this, I do not wish to place any restriction on access to this thesis. _________________________________ __________ Signature Date ii Statement of Sources Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text and a list of references is given. ____________________________________ ____________________ Signature Date iii Acknowledgments My main period of fieldwork was conducted over fifteen months at Warraber Island between July 1996 and September 1997. I am grateful to many Warraberans for their assistance and generosity both during my main fieldwork and subsequent visits to the island. -

EALD Information (PDF, 434

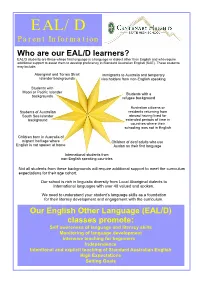

EAL/D Parent Information Who are our EAL/D learners? EAL/D students are those whose first language is a language or dialect other than English and who require additional support to assist them to develop proficiency in Standard Australian English (SAE). These students may include: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Immigrants to Australia and temporary Islander backgrounds visa holders from non-English speaking Students with Maori or Pacific Islander Students with a backgrounds refugee background Australian citizens or Students of Australian residents returning from South Sea islander abroad having lived for background extended periods of time in countries where their schooling was not in English Children born in Australia of migrant heritage where Children of deaf adults who use English is not spoken at home Auslan as their first language International students from non-English speaking countries Not all students from these backgrounds will require additional support to meet the curriculum expectations for their age cohort. Our school is rich in linguistic diversity from Local Aboriginal dialects to International languages with over 40 valued and spoken. We need to understand your student’s language skills as a foundation for their literacy development and engagement with the curriculum. Our English Other Language (EAL/D) classes promote: Self awareness of language and literacy skills Monitoring of language development Intensive teaching for beginners Independence Intentional and explicit teaching of Standard Australian English High Expectations Setting Goals When schools know students speak other languages they can support students in engaging in their learning to reach their educational potential. The information on these questions allows for the right support for your student. -

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island). -

Cape York Region

141°0'E 142°0'E 143°0'E 144°0'E 145°0'E Buru Erubam Le & Warul Ugar (Stephens (Darnley Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on boundaries with areas excluded or discrete boundaries of areas being claimed) as To determine whether any areas fall within the external boundary of an application or Kawa data sourced from Department of Natural Resources, MIsinlaens daendrs E) n#e1rgy (Qld) © ITshlaendtehresy) h#a1ve been recognised by the Federal Court process. determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and State of Queensland for that portion where their data has been used. Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 Topographic vector data is © CommonwealthM aosf iAgu Psteraolipal e(Geoscience Australia) Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. © Commonwealth of Australia 2019 Gebara 2006. and Damuth The applications shown on the map include: Non freehold land tenure sourced from DNRME (QLD) February 2019. - registered applications (i.e. those that have complied with the registration test), The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents Cape York Region Islanders #1 People - new and/or amended applications where the registration test is being applied, and the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give As part oYf atmhe transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in 1998, all - unregistered applications (i.e. -

The Spread of Torres Strait Creole to the Central Islands Of

THE SPREAD OF TORRES STRAIT CREOLE TO THE CENTRAL ISLANDS OF TORRES STRAIT Anna Shnukal INTRODUCTION1 The following paper outlines the second stage of development of Torres Strait Creole, now the lingua franca, or common language, of Torres Strait Islanders everywhere.2 The first stage, which I discussed in an earlier volume of this journal, was that of the creolisation of Pacific Pidgin English around the turn of the century in three Torres Strait island commu nities.3 In that article, I argued that creolisation was the result of two factors not reproduced elsewhere in Torres Strait at the time: (1) the creation of de facto Pacific Islander settle ments on Erub, Ugar and St Paul’s Anglican Mission, Moa, where the Pacific Islanders out numbered Torres Strait Islanders and (2) the integration into those communities of these hitherto marginal immigrants. The prestige of the Pacific Islanders derived from their func tion as linguistic and cultural middlemen, interpreters of European ways of life to their Torres Strait Islander kinfolk. A third stage in the development of the creole began with the war years, when almost all able-bodied men left their home islands to join the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion and, for the first time, came into daily contact with English-speaking Europeans. The present overview article traces the diffusion of Pacific Pidgin English and the creole which developed from it, focusing on the central islands of the Strait between the early 1900s and the beginning of World War II. Also briefly discussed are certain interwoven historical Anna Shnukal carried out research into Torres Strait Creole while a Visiting Research Fellow in Socio linguistics at the Australian Institute o f Aboriginal Studies. -

The Australian ‘Settler’ Colonial-Collective Problem

The Australian ‘Settler’ Colonial-Collective Problem Author Jones, David John Published 2017 Thesis Type Thesis (Professional Doctorate) School Queensland College of Art DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/2241 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/365954 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au The Australian ‘Settler’ Colonial-Collective Problem David John Jones Dip VA, BVA Hons, MAVA Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Visual Arts Queensland College of Art Art, Education and Law Griffith University June 2017 1 Abstract This studio-based project identifies and interrogates the Australian denial of violent national foundation as a ‘settler’ problem, which is framed by the contemporary clinical and social concept of a ‘vicious cycle of anxiety’. The body of work I have produced aims to disrupt the denial of invasion and the erasure of Aboriginal culture through accepted narratives of European settlement of Australia. By aligning collective denial with anxiety, it presents a pathway for remediation through situational exposure; in this case, through works of art. The critical perspective on the invasion and colonisation of Australia is presented in the discursive and non- discursive modes of communication of the coloniser not to arbitrate or appease but to amplify the content. The structure of the exegesis also draws from Aboriginal narrative methodology and integrates with, and is informed by, the studio production in printmaking using demanding traditional European graphic techniques such as etching and aquatint. 2 Statement of Originality: This work has not previously been submitted for a degree or diploma in any university. -

Cape York Region Islanders #1 Non Freehold Land Tenure Sourced from Department of Resources (QLD) March 2021

141°0'E 142°0'E 143°0'E 144°0'E 145°0'E Buru & Erubam Le Warul Kawa Masig People Ugar (Stephens Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based( Doanrnbloeuyndaries with areas excluded or discrete boundaries of areas being claimed) as To determine whether any areas fall within the external boundary of an application or and Damuth Islanders) #1 data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland foIsr ltahnadt etrhse)y # h1ave been recognised by the Federal Court process. determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and People portion where their data has been used. Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 Topographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 Gebara 2006. The applications shown on the map include: Cape York Region Islanders #1 Non freehold land tenure sourced from Department of Resources (QLD) March 2021. - registered applications (i.e. those that have complied with the registration test), The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents - new and/or amended applications where the registration test is being applied, and the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give As part Yofa mthe transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in 1998, all - unregistered applications (i.e. -

Critical Australian Indigenous Histories

Transgressions critical Australian Indigenous histories Transgressions critical Australian Indigenous histories Ingereth Macfarlane and Mark Hannah (editors) Published by ANU E Press and Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Monograph 16 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Transgressions [electronic resource] : critical Australian Indigenous histories / editors, Ingereth Macfarlane ; Mark Hannah. Publisher: Acton, A.C.T. : ANU E Press, 2007. ISBN: 9781921313448 (pbk.) 9781921313431 (online) Series: Aboriginal history monograph Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Indigenous peoples–Australia–History. Aboriginal Australians, Treatment of–History. Colonies in literature. Australia–Colonization–History. Australia–Historiography. Other Authors: Macfarlane, Ingereth. Hannah, Mark. Dewey Number: 994 Aboriginal History is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. The Committee of Management and the Editorial Board Peter Read (Chair), Rob Paton (Treasurer/Public Officer), Ingereth Macfarlane (Secretary/ Managing Editor), Richard Baker, Gordon Briscoe, Ann Curthoys, Brian Egloff, Geoff Gray, Niel Gunson, Christine Hansen, Luise Hercus, David Johnston, Steven Kinnane, Harold Koch, Isabel McBryde, Ann McGrath, Frances Peters- Little, Kaye Price, Deborah Bird Rose, Peter Radoll, Tiffany Shellam Editors Ingereth Macfarlane and Mark Hannah Copy Editors Geoff Hunt and Bernadette Hince Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to Aboriginal History, Box 2837 GPO Canberra, 2601, Australia. Sales and orders for journals and monographs, and journal subscriptions: T Boekel, email: [email protected], tel or fax: +61 2 6230 7054 www.aboriginalhistory.org ANU E Press All correspondence should be addressed to: ANU E Press, The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected], http://epress.anu.edu.au Aboriginal History Inc. -

Issues in the Maintenance of Aboriginal Languages and Aboriginal English

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 378 829 FL 022 748 AUTHOR Malcolm, Ian G. TITLE Issues in the Maintenance of Aboriginal Languages and Aboriginal English. PUB DATE Oct 94 NOTE 19p.; Paper presented at the Annual National Languages Conference of the Australian Federation of Modern Language Teachers' Associations (10th Perth, Western Australia, Australia, October 1-4, 1994). PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.)(120) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PCO1 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Bilingual Education; *English; Foreign Countries; *Indigenous Populations; *Language Maintenance; *Language Planning; Language Variation; *Native Language Instruction; Program Descriptions; Public Policy; *Regional Dialects; Standard Spoken Usage IDENTIFIERS *Australia; Edith Ccwan University (Australia) ABSTRACT Activities at Edith Cowan University (Australia) in support of the maintenance of Aboriginal languages and Aboriginal English are discussed. Discussion begins withan examination of the concept of language maintenance and the reasons it merits the attention of linguists, language planners, and language teachers. Australian policy concerning maintenance of Aboriginal languages is briefly outlined. Research on language maintenance and langyage shift in relation to endangered languages is also reviewed, and the ambiguous role of education in language maintenance is considered. Two areas in which Edith Cowan University has been activeare then described. The first is a pilot study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander language development and maintenance needs and activities,a national initiative with its origins in national language and literacy policy. The second is an effort to mobilize teachers for bidialectal education, in both Aboriginal English and stand,Ardspoken English. The project involves the training of 20 volunteer teachers of Aboriginal children. The role of the university in facilitating change and supporting language maintenance is emphasized. -

Print ED356648.TIF

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 356 648 FL 021 143 AUTHOR Lo Bianco, Joseph, Ed. TITLE VOX: The Journal of the Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education (AACLAME). 1989-1991. INSTITUTION Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education, Canberra. REPORT NO ISSN-1032-0458 PUS DATE 91 NOTE 332p.; Intended to be published twice per year. Two-cone charts and colored photographs may not reproduce well. PUS TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT VOX: The Journal of the Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education; n3-5 1989-1991 EDRS PRICE MfO1 /PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Asian Studies; Bilingual Education; Certification; Communicative Competence (Languages); Comparative Education; Diachronic Linguistics; English (Second Language); Ethnic Groups; Foreign Countries; French; Immersion Programs; Immigrants; Indigenous Populations; Interpretive Skills; Italian; *Language Maintenance; *Language Role; Languages for Special Purposes: Language Tests; Language Variation; *Literacy; Minority Groups; Multicultural Education; Native Language Instruction; Pidgins; Second Language Instruction; Second Language Programs; *Second Languages; Sex; Skill Development; Student Attitudes; Testing IDENTIFIERS Africa; *Australia; Japan; Maori (People); Melanesia; Netherlands; New Zealand; Singapore; Spain ABSTRACT This document consists of the three issues of the aerial "VOX" published in 1989-1991. Major articles in these issues include: "The Original Languages of Australia"; "UNESCO and Universal -

SIF Implementation Specification (Australia) 3.4.8

SIF Implementation Specification (Australia) 3.4.8 table of contents Systems Interoperability Framework™ SIF Implementation Specification (Australia) 3.4.8 March 18, 2021 This version: http://specification.sifassociation.org/Implementation/AU/3.4.8/index.html Previous version: http://specification.sifassociation.org/Implementation/AU/3.4.7/ Latest version: http://specification.sifassociation.org/Implementation/AU/ Schemas SIF_Message (single file, non-annotated) (ZIP archive) SIF_Message (single file, annotated) (ZIP archive) SIF_Message (includes, non-annotated) (ZIP archive) SIF_Message (includes, annotated) (ZIP archive) DataModel (single file, non-annotated) (ZIP archive) DataModel (single file, annotated) (ZIP archive) DataModel (includes, non-annotated) (ZIP archive) DataModel (includes, annotated) (ZIP archive) Note: SIF_Message schemas define every data object element as optional per SIF's Publish/Subscribe and SIF Request/Response Models; DataModel schemas maintain the cardinality of all data object elements. JSON-PESC XSLT JSON-PESC XSLT 3.4.X support (GitHub Repository) Please refer to the errata for this document, which may include some normative corrections. This document is also available in these non-normative formats: ZIP archive, PDF (for printing as a single file), Excel spreadsheet. Copyright ©2021 Systems Interoperability Framework (SIF™) Association. All Rights Reserved. 1 of 564 16/03/2021, 2:20 pm SIF Implementation Specification (Australia) 3.4.8 2 of 564 16/03/2021, 2:20 pm SIF Implementation Specification (Australia) 3.4.8 1 Preamble 1.1 Abstract 1.1.1 What is SIF? SIF is not a product, but a technical blueprint for enabling diverse applications to interact and share data related to entities in the pK-12 instructional and administrative environment. -

Path to Treaty

Report from the Treaty Working Group on Queensland’s PATH TO TREATY February 2020 Copyright Copyright © State of Queensland, February 2020. Copyright protects this publication. Excerpts may be reproduced with acknowledgment of the State of Queensland. This document is licensed by the State of Queensland under a Creative Attribution (CC BY) 3.0 Australian license. CC BY License Summary Statement: In essence, you are free to copy, communicate and adapt the Report from the Treaty Working Group on Queensland’s Path to Treaty as long as you attribute the work to the State of Queensland. To view a copy of this license, visit: www. creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en. While every care has been taken in preparing this publication, the State of Queensland accepts no responsibility for decisions or actions taken as a result of any data, information, statement or advice, expressed or implied, contained within. To the best of our knowledge, the content was correct at the time of publishing. The information in this publication is general and does not take into account individual circumstances or situations. Disclaimer Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islander peoples are warned the photographs in this publication may contain images of deceased persons which may cause sadness or distress. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ...............................................4 Introduction and history 4 Treaties and agreement making 4 Community engagement process and findings 4 Conclusions 5 Recommendations 5 MESSAGE FROM THE TREATY WORKING GROUP ..................................................8 MEET THE TREATY WORKING GROUP AND EMINENT PANEL ..................................8 GLOSSARY AND TERMINOLOGY ........................................................................ 13 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 14 1. A BRIEF HISTORY OF QUEENSLAND ..............................................................