Building Seamless Connectivity CHAPTER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pin-Outs (PDF)

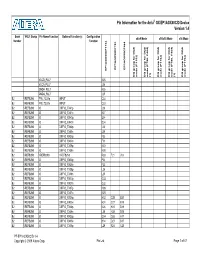

Pin Information for the Arria® GX EP1AGX50C/D Device Version 1.4 Bank VREF Group Pin Name/Function Optional Function(s) Configuration x8/x9 Mode x16/x18 Mode x36 Mode Number Function EP1AGX50DF780 EP1AGX50CF484 EP1AGX50DF1152 DQ group for DQS DQS for group DQ (F1152) mode DQS for group DQ (F780, F484) mode (1) DQS for group DQ (F1152) mode DQS for group DQ (F780, F484) mode (1) DQS for group DQ (F1152) mode VCCD_PLL7 K25 VCCA_PLL7 J26 GNDA_PLL7 K26 GNDA_PLL7 J25 B2 VREFB2N0 FPLL7CLKp INPUT C34 B2 VREFB2N0 FPLL7CLKn INPUT C33 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX41p J28 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX41n K27 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX40p E34 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX40n D34 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX40p J30 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX40n J29 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX39p F32 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX39n F31 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX39p K30 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX39n K29 B2 VREFB2N0 VREFB2N0 VREFB2N0 R30 T21 J18 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX38p F34 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX38n F33 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX38p L26 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX38n L25 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX37p G33 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX37n G32 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX37p M26 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX37n M25 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX36p H32 C28 B20 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX36n H31 C27 B19 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX36p K28 H23 D19 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX36n L28 H22 D18 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX35p G34 D28 A17 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX35n H34 D27 B17 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX35p L29 F24 C20 PT-EP1AGX50C/D-1.4 Copyright © 2009 Altera Corp. Pin List Page 1 of 47 Pin Information for the Arria® GX EP1AGX50C/D Device Version -

AH16 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health

AH16 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health www.racgp.org.au Healthy Profession. Healthy Australia. AH16 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health Disclaimer The information set out in this publication is current at the date of first publication and is intended for use as a guide of a general nature only and may or may not be relevant to particular patients or circumstances. Nor is this publication exhaustive of the subject matter. Persons implementing any recommendations contained in this publication must exercise their own independent skill or judgement or seek appropriate professional advice relevant to their own particular circumstances when so doing. Compliance with any recommendations cannot of itself guarantee discharge of the duty of care owed to patients and others coming into contact with the health professional and the premises from which the health professional operates. Accordingly, The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) and its employees and agents shall have no liability (including without limitation liability by reason of negligence) to any users of the information contained in this publication for any loss or damage (consequential or otherwise), cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on the information contained in this publication and whether caused by reason of any error, negligent act, omission or misrepresentation in the information. Recommended citation The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Curriculum for Australian General Practice 2016 – AH16 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. East Melbourne, Vic: RACGP, 2016. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 100 Wellington Parade East Melbourne, Victoria 3002 Australia Tel 03 8699 0510 Fax 03 9696 7511 www.racgp.org.au Published May 2016 © The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners We recognise the traditional custodians of the land and sea on which we work and live. -

Ilex Specifications

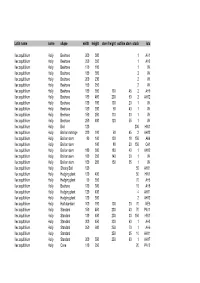

Latin name name shape width height stem height outline stem stock lots Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 200 300 1 AH1 Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 250 350 1 AH2 Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 170 180 1 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 180 350 2 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 200 230 2 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 150 250 2 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 180 350 130 45 2 AH9 Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 180 450 200 60 2 AH12 Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 130 180 100 20 1 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 180 200 50 40 1 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 150 250 110 30 1 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 250 400 120 55 1 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Ball 120 200 HW1 Ilex aquifolium Holly Ball on mini tige 220 180 60 45 2 AH12 Ilex aquifolium Holly Ball on stem 80 160 100 18 150 AK4 Ilex aquifolium Holly Ball on stem 160 80 20 150 CA1 Ilex aquifolium Holly Ball on stem 180 300 180 40 1 AH12 Ilex aquifolium Holly Ball on stem 180 250 140 30 1 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Ball on stem 150 250 150 35 1 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Shruby Ball 120 55 AH11 Ilex aquifolium Holly Hedging plant 120 400 50 HW1 Ilex aquifolium Holly Hedging plant 60 350 70 AH5 Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 130 300 15 AH6 Ilex aquifolium Holly Hedging plant 120 400 4 AH11 Ilex aquifolium Holly Hedging plant 120 350 2 AH12 Ilex aquifolium Holly Half standard 100 180 100 20 70 NE5 Ilex aquifolium Holly Standard 150 450 200 40 70 PA11 Ilex aquifolium Holly Standard 130 450 200 30 150 HW1 Ilex aquifolium Holly Standard 300 450 200 60 1 AH3 Ilex aquifolium Holly Standard 350 600 -

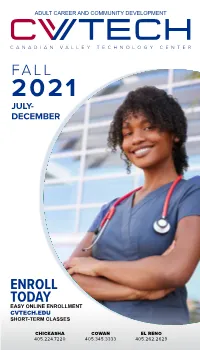

Enroll Today Easy Online Enrollment Cvtech.Edu Short-Term Classes

ADULT CAREER AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT CANADIAN VALLEY TECHNOLOGY CENTER FALL 2021 JULY- DECEMBER ENROLL TODAY EASY ONLINE ENROLLMENT CVTECH.EDU SHORT-TERM CLASSES CHICKASHA COWAN EL RENO 405.224.7220 405.345.3333 405.262.2629 FALL 2021 CATALOG TABLE OF CONTENTS SHORT-TERM COURSES | JULY-DECEMBER ONLINE & BLENDED DANCING / MUSIC ....................................................4 FABRIC / YARN ...........................................................4 ALL ONLINE & BLENDED COURSES .................. 2 HEALTH / WELLNESS. ............................................. 5 BUSINESS HOME / AUTO MAINTENANCE. ........................... 5 & COMPUTERS LANGUAGE ................................................................ 5 MISCELLANEOUS .................................................... 5 ACCOUNTING / QUICKBOOKS ............................ 2 PERSONAL FINANCE. ............................................. 5 COMPUTER BASICS ................................................ 2 WRITING...................................................................... 5 COMPUTER CERTIFICATIONS .............................. 2 MICROSOFT OFFICE ............................................... 2 MODERN DESIGN / CADD ..................................2-3 TRADE, SAFETY & INDUSTRY HEALTH AUTOMOTIVE / DRIVING ....................................... 5 CPR / FIRST AID .........................................................3 ENERGY INDUSTRY ................................................. 5 DENTAL FIELD ............................................................3 -

Salem Generating Station, Units 1 & 2, Revision 29 to Updated Final Safety Analysis Report, Chapter 4, Figures 4.5-1 to 4.5

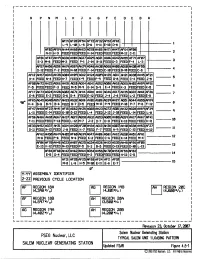

r------------------------------------------- 1 I p M J B I R N L K H G F E D c A I I I I I Af'Jq AF20 AF54 AF72 32 AF52 AF18 I L-q L-10 L-15 D-6 -11 E-10 D-8 l I AF03 Af't;qAH44 AH60 AH63 AG70 AH65 AH7l AH47 AFS4 AF08 I N-ll H-3 FEED FEED FEED H-14 FEED FEED FEED M-12 C-11 2 I AF67 AH4q AH04 AG27 AG2<i' AG21 AG16 AG42 AF71 AF07 AF01 AG36 AH!5!5 3 I E-3 M-6 FEED M-3 FEED P-1 J-14 B-11 FEED D-3 FEED F-4 L-3 I AF67 AH5S AG56 Atflq AGsq AH2<1' AG48 AH30 AG68 AH08 AG60 AH30 AF55 I D-12 FEED F-2 FEED N-11 FEED F-14 FEED C-11 FEED B-11 FEED C-8 4 I AF12 AH57 AG43 AH38 AHtiJq AG12 AH24 AGfR AH25 AGil AG31 AH45 AF21 AGlM AH21 5 I H~4 FEED N-4 FEED H-7 FEED K~q FEED F-q FEED G-8 FEED C-4 FEED J-15 I AF50 AH72 AH22 AGS6 AH15 AGll.lAG64 AG41 AG52 AG88 AH18 AG65 AHIJ2 AH5q AF51 I F-5 FEED FEED F-3 FEED M-5 r+q G-14 o-q E-4 FEED K-3 FEED FEED K-5 6 I f:Fl7 AH73 AG24 AH28 AG82 AG71 AH14 AG18 AHil AG46 AG17 AH35 AG22 AH61 AF26 7 I E-8 FEED E-2 FEED G-6 G-4 FEED E-12 FEED J-4 J-6 FEED L-2 FEED E-5 I Af&q I qeo AF65 AG45 AtM0 AG57 AH33 AG32 AG16 AH01 AGI6 AG3<1' AH27 AG51 AG44 AG55 K-4 B-8 e-q B-6 FEED B-7 P-5 FEEC M-11 P-q FEED P-11 P-7 P-8 F-12 8 I AF47 AH68 AF23 AH41 AF1!5 AG62 AH26 AG03 AH23 AH32 AG28 AHsq AF3<1' q I L-U FEED E-14 FEED G-10 G-12 FEED L-4 FEED FEED L-14 FEED L-8 I ~~ AF66 AH66 AH10 AG67 AH37 AGJq AG68 AG3l AG63 AG05 AH08 AG5q AH17 AH67 AF41 I F-11 FEED FEED F-13 FEED L-12 M-7 J-2 D-7 D-11 FEED K-13 FEED FEED K-11 10 I AE33 AH!52 AG37 AH31 AG14 AH20 AF20 AH34 AG13 AH36 AG07 AH40 AG38 AH!53 AF27 I G-ll FEED N-12 FEED J-8 FEED K-7 FEED -

The Transport Trend of Thailand and Malaysia

Executive Summary Report The Potential Assessment and Readiness of Transport Infrastructure and Services in Thailand for ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) Content Page 1. Introduction 1.1 Rationales 1 1.2 Objectives of Study 1 1.3 Scopes of Study 2 1.4 Methodology of Study 4 2. Current Status of Thailand Transport System in Line with Transport Agreement of ASEAN Community 2.1 Master Plan and Agreement on Transport System in ASEAN 5 2.2 Major Transport Systems for ASEAN Economic Community 7 2.2.1 ASEAN Highway Network 7 2.2.2 Major Railway Network for ASEAN Economic Community 9 2.2.3 Main Land Border Passes for ASEAN Economic Community 10 2.2.4 Main Ports for ASEAN Economic Community 11 2.2.5 Main Airports for ASEAN Economic Community 12 2.3 Efficiency of Current Transport System for ASEAN Economic Community 12 3. Performance of Thailand Economy and Transport Trend after the Beginning of ASEAN Economic Community 3.1 Factors Affecting Cross-Border Trade and Transit 14 3.2 Economic Development for Production Base Thriving in Thailand 15 3.2.1 The analysis of International Economic and Trade of Thailand and ASEAN 15 3.2.2 Major Production Bases and Commodity Flow of Prospect Products 16 3.2.3 Selection of Potential Industries to be the Common Production Bases of Thailand 17 and ASEAN 3.2.4 Current Situation of Targeted Industries 18 3.2.5 Linkage of Targeted Industries at Border Areas, Important Production Bases, 19 and Inner Domestic Areas TransConsult Co., Ltd. King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi 2T Consulting and Management Co., Ltd. -

Structure of ATP Synthase from Paracoccus Denitrificans Determined by X-Ray Crystallography at 4.0 Å Resolution

Structure of ATP synthase from Paracoccus denitrificans determined by X-ray crystallography at 4.0 Å resolution Edgar Morales-Riosa, Martin G. Montgomerya, Andrew G. W. Leslieb,1, and John E. Walkera,1 aMedical Research Council Mitochondrial Biology Unit, Cambridge Biomedical Campus, Cambridge CB2 0XY, United Kingdom; and bMedical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge Biomedical Campus, Cambridge CB2 0QH, United Kingdom Contributed by John E. Walker, September 4, 2015 (sent for review July 28, 2015; reviewed by Stanley D. Dunn, Robert H. Fillingame, and Dale Wigley) The structure of the intact ATP synthase from the α-proteobacterium mitochondrial enzyme that have no known role in catalysis (2). Paracoccus denitrificans ζ , inhibited by its natural regulatory -protein, Structures have been described of the F1 domains of the enzymes has been solved by X-ray crystallography at 4.0 Å resolution. The from Escherichia coli (10, 11), Caldalkalibacillus thermarum (12), ζ-protein is bound via its N-terminal α-helix in a catalytic interface in and Geobacillus stearothermophilus (formerly Bacillus PS3) (13); of the F1 domain. The bacterial F1 domain is attached to the membrane the α3β3-subcomplex of the F1 domain from G. stearothermophilus domain by peripheral and central stalks. The δ-subunit component of (14); and of isolated c-rings from the rotors of several species (15– the peripheral stalk binds to the N-terminal regions of two α-subunits. 19). There is also structural information on the peripheral stalk The stalk extends via two parallel long α-helices, one in each of the region of the F-ATPase from E. -

Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity

Association of Southeast Asian Nations Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity One Vision, One Identity, One Community i HA NOI DECLARATION ON THE ADOPTION OF THE MASTER PLAN ON ASEAN CONNECTIVITY WE, the Heads of State/Government of Brunei Darussalam, the Kingdom of Cambodia, the Republic of Indonesia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Malaysia, the Union of Myanmar, the Republic of the Philippines, the Republic of Singapore, the Kingdom of Thailand and the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, on the occasion of the 17th ASEAN Summit; Recalling the ASEAN Leaders’ Statement on ASEAN Connectivity issued in Cha-am Hua Hin, Thailand, on 24 October 2009; Reaffirming that enhancing intra-regional connectivity within ASEAN would benefit all ASEAN Member States through enhanced trade, investment, tourism, people-to-people exchanges, and development which would complement the ongoing regional efforts to realise a people-oriented ASEAN Community by 2015; Welcoming the work of the High Level Task Force on ASEAN Connectivity in developing the Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity with the ASEAN Secretariat and relevant sectoral bodies, in cooperation with international organisations such as Asian Development Bank (ADB), Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA), United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) and World Bank; Recognising that the Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity will promote economic growth, narrow development gaps, ASEAN integration and Community building process, enhance competitiveness of ASEAN, promote deeper social and cultural understanding as well as greater people mobility and connect its Member States within the region and with the rest of the world; Expressing appreciation for the support shown by our Dialogue Partners towards the ASEAN Connectivity initiative and their readiness to partner with ASEAN in the implementation of the Master Plan. -

Oneida County Legislative District 1 Date: April 1, 2014

CARTER RD D D 5 R R 6 B T 3 L L I E P L P S A T K E U C E T 5 C 6 K R D D U W O 3 M R W O D E O R S E R A K T R L Y T N C E E A A S E U D H G R I C Y T O I E O E D E R ID R A R A T R N N R F D C R D E W E O R N S E G S N D R H R E T D T E E S E A L D H S E E R I R T O S T U R I 10 D R M S N W I S R A G E A C N L H R T Y Verona D R AC11 AC12 AC13 AC14 AC15 E AC16 AC17 AC18 H AC19 R C R W H T L D R E I IL D L D D R L S E VERONA 4 R E B R M U N L R D I E T A K C K H A C O O U R S 6 R TA R N D TE 2 D R T OU R LO TE W E 31 Y EL T L U D R D R D O E R R L L B N R O E S T G E N T W E D I B A R L T O D S R NS E D T A D S A M M R R R T H 4 WESTMORELAND 3 R E C E N R RO A E N R E U FR TE N D U G Y T H B R 31 D D R S I I L D E R Y 5 YD R L R 6 L BO R D 5 L R N 3 I I 6 E SPR R H A 3 ING RD M M G E D S 3 R M E L I E T O E W N U T R EL I F U L I O RD E S L R O PR I-90 R D R ING STAT D E RD I- E R T E 90 OU T T A D AD11 AD12 AD13 E AD14 T A AD15 AD16 AD17 AD18 AD19 31 S T R S I-90 I-90 H 0 T I-9 L I OW D E R M S LL S PR VERONA 3 L ING H RD IL 0 OUS H I-90 I-9 E RD FOSTE D R CORN N ERS RD A T S S N D I R A E I-90 R M O Y I-90 O IL DA 5 M D D R 36 I-90 I-90 R E S A T -90 MIT G I C HEL S E U L R WN L R D O I O D T NE N R I D R I-90 I R RD S K SK KINNE R N 0 E N T RD -9 T 5 E I I E 0 L A 6 R L 9 S A J I- P 3 D D T T S R WESTMORELAND 4 D S E Y R E A LL R E W T N E C NL D T H O O E U H C L T F I R O R I L L M E O I R O L L X M W U D IL HIL E L T R R O M 0 T I-9 A E D E O R IN AE11 AE12 AE1R 3 T AE14 D AE15 AE16 L AE17 AE18 AE19 R D S R 3 N C D 1 E EN OW TE -

CADP 2.0) Infrastructure for Connectivity and Innovation

The Comprehensive Asia Development Plan 2.0 (CADP 2.0) Infrastructure for Connectivity and Innovation November 2015 Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia, its Governing Board, Academic Advisory Council, or the institutions and governments they represent. All rights reserved. Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted with proper acknowledgement. Cover Art by Artmosphere ERIA Research Project Report 2014, No.4 National Library of Indonesia Cataloguing in Publication Data ISBN: 978-602-8660-88-4 Contents Acknowledgement iv List of Tables vi List of Figures and Graphics viii Executive Summary x Chapter 1 Development Strategies and CADP 2.0 1 Chapter 2 Infrastructure for Connectivity and Innovation: The 7 Conceptual Framework Chapter 3 The Quality of Infrastructure and Infrastructure 31 Projects Chapter 4 The Assessment of Industrialisation and Urbanisation 41 Chapter 5 Assessment of Soft and Hard Infrastructure 67 Development Chapter 6 Three Tiers of Soft and Hard Infrastructure 83 Development Chapter 7 Quantitative Assessment on Hard/Soft Infrastructure 117 Development: The Geographical Simulation Analysis for CADP 2.0 Appendix 1 List of Prospective Projects 151 Appendix 2 Non-Tariff Barriers in IDE/ERIA-GSM 183 References 185 iii Acknowledgements The original version of the Comprehensive Asia Development Plan (CADP) presents a grand spatial design of economic infrastructure and industrial placement in ASEAN and East Asia. Since the submission of such first version of the CADP to the East Asia Summit in 2010, ASEAN and East Asia have made significant achievements in developing hard infrastructure, enhancing connectivity, and participating in international production networks. -

Mapping the Links Between ASEAN and the GMS, BIMP-EAGA, and IMT-GT

REGIONAL AND SUBREGIONAL PROGRAM LINKS Mapping the links between ASEAN and the GMS, BIMP-EAGA, and IMT-GT REGIONAL AND SUBREGIONAL PROGRAM LINKS Mapping the links between ASEAN and the GMS, BIMP-EAGA, and IMT-GT September 2013 © 2013 Asian Development Bank All rights reserved. Published 2013. Printed in the Philippines. ISBN 978-92-9254-202-3 (Print), 978-92-9254-203-0 (PDF) Publication Stock No. RPT135922-2 Cataloging-In-Publication Data Regional and Subregional Program Links: mapping the links between ASEAN and the GMS, BIMP-EAGA, and IMT-GT Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Asian Development Bank, 2013. 1. Regional cooperation and integration. 2. ASEAN. 3. GMS. 4. BIMP-EAGA. 5. IMT-GT. I. Asian Development Bank. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. Use of the term “country” does not imply any judgment by the authors or ADB as to the legal or other status of any territorial entity. The symbol “$” represents the United States dollar unless otherwise indicated. “Asia” refers only to ADB’s Asian member economies. ADB encourages printing or copying information exclusively for personal and noncommercial use with proper acknowledgement of ADB. Users are restricted from reselling, redistributing, or creating derivative works for commercial purposes without the express, written consent of ADB. Photo credits (cover): ADB photo archive and Josephine Duque-Comia. -

C.106 BCZ 3.81/../180 Technical Data Product Data Accessories BCZ 3.81

Connectors in 3.81 mm pitch Series BC/SC 3.81 BCZ 3.81/../180 Product data BCZ 3.81/../180 IEC: 320 V / 17.5 A / 0.2 - 1.5 mm² UL: 300 V / 10 A / AWG 28 - 16 For additional articles and information, refer to catalog.weidmueller.com OMNIMATE Signal OMNIMATE PCB Connectors Note: • Additional colours on request • Gold-plated contact surfaces on request • Rated current related to rated cross-section and min. No. of poles. • Wire end ferrule without plastic collar to DIN 46228/1 • Wire end ferrule with plastic collar to DIN 46228/4 Female plug with screw connection. Wire outlet • P on drg. = pitch 180° (wire is straight on to the direction of • Rated data refer only to the component itself. Clearance and plugging). creepage distances to other components are to be designed • Available in closed version, with screw flange in accordance with the relevant application standards. Dimensioned drawing C (F) and lock and release-lever (LR). Weidmüller’s 3.81-mm-pitch (0.15 inch) plug-in connectors are compatible with the L1 + P 16,1 layouts of standard connectors and offer 0.634" space for labelling and coding. 11,1 0.437" P 9 0.354" L1 Technical data Accessories Ordering data In compliance with IEC 60664-1 / IEC 61984 Note: Refer to the Accessories chapter for additional accessories. Solder pin length Clamping range, max. mm² 0.08...1.5 Hood Order No. Colour orange black Solid core H05(07) V-U mm² 0.2...1.5 BCZ 3.81 AH03 1005280000 Pitch 3.81 mm Stranded H07 V-R BCZ 3.81 AH04 1005290000 Pol.