Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 11:59:31AM Via Free Access 362 Appendix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MMB PP FROMMER's SHANGHAI DAY by DAY NOV 2011-Cover.Jpg

S h a n Hua W G D x a u a i i t o n sheng zhen n Lu s m P u Bund n u L Jade Buddha Hengfeng LuHANZHONG Historicala Huangpu d u o QufLu Bus Station u Y n Temple RD MuseumPark g N N o PUDONG Oriental Pearl a r n Lu BUND n t X me Lu h i ia TV Tower L z X / XINZHA Lujiazui u S a o C RD n The Park u h g g HUANGPU Riverside t an Sh Datian h e B u Bund Ch n zh Lu u e iu EAST Park Century Ave. im E g L N LUJIAZUI g i Holy Trinity a x d L NANJING RD Lujiazui Xi Lu n p on JING’AN en E u u g D r Cathedral hu Lu e ng B iji ng Super Brand s e e Do a Taixing Lu l s B Central Wuging Lu r i PEOPLE’S SQ L w Lu L n Dong Mall u u FuzhouHenan Lu u a a g L u Lu Hospital y an ng Jiujiangn kLuo Renji R y ji a Shanghai ( ng H Yan’ iv Jia e e n Lu Tunne F a Hospital e l r World Financial e g Lu Shanghai s n N don Zhong Lu v g i gning Lu uan d Lu a Shanghai MoCA G Museum of e Center i t Z P X e Shanghai h r H P d Natural History o o Art n u m u WEST ) People’s Urban Planning a m g n e NANJING Museum sh g n in jing Park Exhibition Hall a p a g ei S i Dong Lu min Lu n u d B en L RD h R Gucheng R e Shanghai D u i o iv u m Ningha Park n e i L g r X e Grand Theater Fuyou Lu n Shanghai E ng Shanghai Z r ji h an Y Yuyuan L N Concert Hall Fuyou Rd o u Lu i Museum ai n ih L Garden e u Mosque g Shanghai W u Square L ng DASHIJIE h Exhibition Dagu Lu o H u Park Zh enan a City God Yan’an Zhong Lu g Center lin Shuguang Jin u Jing’an Yan’an Freeway (elevated) Temple Huaihai Hospital L Paramount SOUTH u xing L TempleJING’AN Fu nel R Bird, Fish, Flower & n Ballroom HUANGPI Park -

Modernism in Practice: Shi Zhecun's Psychoanalytic Fiction Writing

Modernism in Practice: Shi Zhecun's Psychoanalytic Fiction Writing Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Zhu, Yingyue Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 14:07:54 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/642043 MODERNISM IN PRACTICE: SHI ZHECUN’S PSYCHOANALYTIC FICTION WRITING by Yingyue Zhu ____________________________ Copyright © Yingyue Zhu 2020 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Master’s Committee, we certify that we have read the thesis prepared by Yingyue Zhu, titled MODERNISM IN PRACTICE: SHI ZHECUN’S PSYCHOANALYTIC FICTION WRITING and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Master’s Degree. Jun 29, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Dian Li Fabio Lanza Jul 2, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Fabio Lanza Jul 2, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Scott Gregory Final approval and acceptance of this thesis is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the thesis to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this thesis prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the Master’s requirement. -

The New Sensationists

Edinburgh Research Explorer The new sensationists Citation for published version: Rosenmeier, C 2018, The new sensationists: Shi Zhecun, Mu Shiying, Liu Na'ou. in MD Gu (ed.), The Routledge Companion of Modern Chinese Literature. 1 edn, Routledge, pp. 168-180. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: The Routledge Companion of Modern Chinese Literature Publisher Rights Statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge in Routledge Handbook of Modern Chinese Literature on 3/09/2018, available online: https://www.routledge.com/Routledge-Handbook-of-Modern- Chinese-Literature/Gu/p/book/9781138647541 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 The New Sensationists: Shi Zhecun, Mu Shiying, and Liu Na’ou, Introduction The three writers under consideration here—Shi Zhecun (1905–2003), Mu Shiying (1912– 1940), and Liu Na’ou (1905–1940)—were the foremost modernist authors in the Republican period. Collectively labelled “New Sensationists” (xinganjuepai), they were mainly active in Shanghai in the early 1930s, and their most famous works reflect the speed, chaos, and intensity of the metropolis.1 They wrote about dance halls, neon lights, and looming madness alongside modern lifestyles, gender roles, and social problems. -

Virtual Shanghai

ASIA mmm i—^Zilll illi^—3 jsJ Lane ( Tail Sttjaca, New Uork SOif /iGf/vrs FO, LIN CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION Draper CHINA AND THE CHINESE L; THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 House 1918 WINE ATJD~SPIRIT MERCHANTS. PROVISION DEALERS. SHIP CHANDLERS. yigents for jfidn\iratty C/jarts- HOUSE BOATS supplied with every re- quisite for Up-Country Trips. LANE CRAWFORD 8 CO., LTD., NANKING ROAD, SHANGHAI. *>*N - HOME USE RULES e All Books subject to recall All borrowers must regis- ter in the library to borrow books fdr home use. All books must be re- turned at end of college year for inspection and repairs. Limited books must be returned within the four week limit and not renewed. Students must return all books before leaving town. Officers should arrange for ? the return of books wanted during their absence from town. Volumes of periodicals and of pamphlets are held in the library as much as possible. For special pur- poses they are given out for a limited time. Borrowers should not use their library privileges for the benefit of other persons Books of special value nd gift books," when the giver wishes it, are not allowed to circulate. Readers are asked to re- port all cases of books marked or mutilated. Do not deface books by marks and writing. - a 5^^KeservaToiioT^^ooni&^by mail or cable. <3. f?EYMANN, Manager, The Leading Hotel of North China. ^—-m——aaaa»f»ra^MS«»» C UniVerS"y Ubrary DS 796.S5°2D22 Sha ^mmmmilS«u,?,?llJff travellers and — — — — ; KELLY & WALSH, Ltd. -

Chinese Literature in the Second Half of a Modern Century: a Critical Survey

CHINESE LITERATURE IN THE SECOND HALF OF A MODERN CENTURY A CRITICAL SURVEY Edited by PANG-YUAN CHI and DAVID DER-WEI WANG INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS • BLOOMINGTON AND INDIANAPOLIS William Tay’s “Colonialism, the Cold War Era, and Marginal Space: The Existential Condition of Five Decades of Hong Kong Literature,” Li Tuo’s “Resistance to Modernity: Reflections on Mainland Chinese Literary Criticism in the 1980s,” and Michelle Yeh’s “Death of the Poet: Poetry and Society in Contemporary China and Taiwan” first ap- peared in the special issue “Contemporary Chinese Literature: Crossing the Bound- aries” (edited by Yvonne Chang) of Literature East and West (1995). Jeffrey Kinkley’s “A Bibliographic Survey of Publications on Chinese Literature in Translation from 1949 to 1999” first appeared in Choice (April 1994; copyright by the American Library Associ- ation). All of the essays have been revised for this volume. This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by David D. W. Wang All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

The Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun Wei-Yi Lee University of Colorado Boulder, [email protected]

University of Colorado, Boulder CU Scholar Comparative Literature Graduate Theses & Comparative Literature Dissertations Summer 7-18-2014 Psychoanalyzed Vacillation between and Entanglement of the Old and the New in 1930s Shanghai: the Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun Wei-Yi Lee University of Colorado Boulder, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.colorado.edu/coml_gradetds Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Wei-Yi, "Psychoanalyzed Vacillation between and Entanglement of the Old and the New in 1930s Shanghai: the Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun" (2014). Comparative Literature Graduate Theses & Dissertations. Paper 3. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Comparative Literature at CU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Literature Graduate Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CU Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Psychoanalyzed Vacillation between and Entanglement of the Old and the New in 1930s Shanghai: the Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun by WEI-YI LEE B.A., National Taiwan University, 2005 M.A., National Chengchi University, 2008 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Comparative Literature Graduate Program 2014 This thesis entitled: Psychologized Vacillation between and Entanglement of the Old and the New in 1930s Shanghai: the Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun written by Wei-Yi Lee has been approved for Comparative Literature Graduate Program Chair: Dr. -

Portuguese in Shanghai

CONTENTS Introduction by R. Edward Glatfelter 1 Chapter One: The Portuguese Population of Shanghai..........................................................6 Chapter Two: The Portuguese Consulate - General of Shanghai.........................................17 ---The Personnel of the Portuguese Consulate-General at Shanghai.............18 ---Locations of the Portuguese Consulate - General at Shanghai..................23 Chapter Three: The Portuguese Company of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps........................24 ---Founding of the Company.........................................................................24 ---The Personnel of the Company..................................................................31 Activities of the Company.............................................................................32 Chapter Four: The portuguese Cultural Institutions and Public Organizations....................36 ---The Portuguese Press in Shanghai.............................................................37 ---The Church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus...................................................39 ---The Apollo Theatre....................................................................................39 ---Portuguese Public Organizations...............................................................40 Chapter Five: The Social Problems of the Portuguese in Shanghai.....................................45 ---Employment Problems of the Portuguese in Shanghai..............................45 ---The Living Standard of the Portuguese in Shanghai.................................47 -

GÉRALDINE A. FISS (許潔琳), Ph.D

Updated July 16, 2020 GÉRALDINE A. FISS (許潔琳), Ph.D. East Asian Languages and Cultures University of Southern California Taper Hall of Humanities, 356E Los Angeles, CA 90089-0357 [email protected] ACADEMIC POSITIONS Scholar in Residence, 2020 – present. University of Southern California Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures. Lecturer, 2015 - 2020. University of Southern California Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures. Postdoctoral Research Associate, 2010 - 2015. University of Southern California Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures. EDUCATION Harvard University, Ph.D. East Asian Languages and Civilizations (2008) Concentration Fields: Modern Chinese Literature, Intellectual History and Film; Late Imperial Chinese Literature and Thought; Tokugawa and Meiji Japanese History and Thought Dissertation: Textual Travels and Traveling Texts: Tracing Encounters with German Culture, Literature and Thought in Late Qing and Early Republican China. Dissertation Advisers: Professor David Wang, Professor Wilt Idema, Professor Wai-yee Li Smith College, B.A. East Asian Languages and Literatures, cum laude with highest honors (1997) Major: East Asian Languages and Literatures Minor: German Literature and Culture Studies LANGUAGES Mandarin Chinese: advanced level of fluency Modern Japanese: intermediate level of fluency Classical Chinese and Latin: reading knowledge English, German, French and Swedish: native fluency RESEARCH INTERESTS Transcultural Intertextuality in Modern and Contemporary Chinese Poetics, Literature and Film Chinese-German, East-West, and Sino-Japanese Literary, Aesthetic and Cinematic Relations Chinese Women’s Literature, Cinema and Thought Chinese Dissident Poetry, Fiction and Film The Fantastic in East Asian Literature and Film Chinese and East Asian Ecocriticism, Ecopoetry and Ecocinema JOURNAL ARTICLES AND BOOK CHAPTERS Fiss, Géraldine. -

Read the Introduction

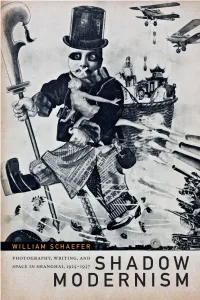

William Schaefer PhotograPhy, Writing, and SPace in Shanghai, 1925–1937 Duke University Press Durham and London 2017 © 2017 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Text designed by Mindy Basinger Hill Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schaefer, William, author. Title: Shadow modernism : photography, writing, and space in Shanghai, 1925–1937 / William Schaefer. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and ciP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017007583 (print) lccn 2017011500 (ebook) iSbn 9780822372523 (ebook) iSbn 9780822368939 (hardcover : alk. paper) iSbn 9780822369196 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcSh: Photography—China—Shanghai—History—20th century. | Modernism (Art)—China—Shanghai. | Shanghai (China)— Civilization—20th century. Classification: lcc tr102.S43 (ebook) | lcc tr102.S43 S33 2017 (print) | ddc 770.951/132—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007583 Cover art: Biaozhun Zhongguoren [A standard Chinese man], Shidai manhua (1936). Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University Libraries. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the University of Rochester, Department of Modern Languages and Cultures and the College of Arts, Sciences, and Engineering, which provided funds toward the publication -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Dreams and disillusionment in the City of Light : Chinese writers and artists travel to Paris, 1920s-1940s Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/07g4g42m Authors Chau, Angie Christine Chau, Angie Christine Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Dreams and Disillusionment in the City of Light: Chinese Writers and Artists Travel to Paris, 1920s–1940s A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Angie Christine Chau Committee in charge: Professor Yingjin Zhang, Chair Professor Larissa Heinrich Professor Paul Pickowicz Professor Meg Wesling Professor Winnie Woodhull Professor Wai-lim Yip 2012 Signature Page The Dissertation of Angie Christine Chau is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ...................................................................................................................iii Table of Contents............................................................................................................... iv List of Illustrations.............................................................................................................. v Acknowledgements........................................................................................................... -

The University of Chicago Sound Images, Acoustic

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO SOUND IMAGES, ACOUSTIC CULTURE, AND TRANSMEDIALITY IN 1920S-1940S CHINESE CINEMA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DEVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY LING ZHANG CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2017 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………………iii Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………. x Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter One Sound in Transition and Transmission: The Evocation and Mediation of Acoustic Experience in Two Stars in the Milky Way (1931) ...................................................................................................................................................... 20 Chapter Two Metaphoric Sound, Rhythmic Movement, and Transcultural Transmediality: Liu Na’ou and The Man Who Has a Camera (1933) …………………………………………………. 66 Chapter Three When the Left Eye Meets the Right Ear: Cinematic Fantasia and Comic Soundscape in City Scenes (1935) and 1930s Chinese Film Sound… 114 Chapter Four An Operatic and Poetic Atmosphere (kongqi): Sound Aesthetic and Transmediality in Fei Mu’s Xiqu Films and Spring in a Small Town (1948) … 148 Filmography…………………………………………………………………………………………… 217 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………………… 223 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Over the long process of bringing my dissertation project to fruition, I have accumulated a debt of gratitude to many gracious people who have made that journey enjoyable and inspiring through the contribution of their own intellectual vitality. First and foremost, I want to thank my dissertation committee for its unfailing support and encouragement at each stage of my project. Each member of this small group of accomplished scholars and generous mentors—with diverse personalities, academic backgrounds and critical perspectives—has nurtured me with great patience and expertise in her or his own way. I am very fortunate to have James Lastra as my dissertation co-chair. -

The Chinese Nationalists' Attempt to Regulate Shanghai, 1927-49 Author(S): Frederic Wakeman, Jr

Licensing Leisure: The Chinese Nationalists' Attempt to Regulate Shanghai, 1927-49 Author(s): Frederic Wakeman, Jr. Source: The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 54, No. 1 (Feb., 1995), pp. 19-42 Published by: Association for Asian Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2058949 . Accessed: 23/03/2014 13:05 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Association for Asian Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Asian Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 130.132.173.206 on Sun, 23 Mar 2014 13:05:48 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions LicensingLeisure: The ChineseNationalists' Attempt to RegulateShanghai, 1927-49 FREDERIC WAKEMAN, JR. Shanghaihas oftenbeen called the Parisof the Orient.This is onlyhalf true. Shanghaihas all the vicesof Parisand morebut boastsof noneof its cultural influences.The municipalorchestra is uncertainof its future,and the removalof thecity library to its newpremises has only shattered our hopes for better reading facilities.The RoyalAsiatic Society has beendenied all supportfrom the Council forthe maintenanceof its library,which is the onlycenter for research in this metropolis.It is thereforeno wonderthat men and women, old or young,poor or rich,turn their minds to mischiefand lowlypursuits of pleasure,and the laxity ofpolice regulations has aggravatedthe situation.