The New Sensationists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modernism in Practice: Shi Zhecun's Psychoanalytic Fiction Writing

Modernism in Practice: Shi Zhecun's Psychoanalytic Fiction Writing Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Zhu, Yingyue Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 14:07:54 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/642043 MODERNISM IN PRACTICE: SHI ZHECUN’S PSYCHOANALYTIC FICTION WRITING by Yingyue Zhu ____________________________ Copyright © Yingyue Zhu 2020 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Master’s Committee, we certify that we have read the thesis prepared by Yingyue Zhu, titled MODERNISM IN PRACTICE: SHI ZHECUN’S PSYCHOANALYTIC FICTION WRITING and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Master’s Degree. Jun 29, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Dian Li Fabio Lanza Jul 2, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Fabio Lanza Jul 2, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Scott Gregory Final approval and acceptance of this thesis is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the thesis to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this thesis prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the Master’s requirement. -

Chinese Literature in the Second Half of a Modern Century: a Critical Survey

CHINESE LITERATURE IN THE SECOND HALF OF A MODERN CENTURY A CRITICAL SURVEY Edited by PANG-YUAN CHI and DAVID DER-WEI WANG INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS • BLOOMINGTON AND INDIANAPOLIS William Tay’s “Colonialism, the Cold War Era, and Marginal Space: The Existential Condition of Five Decades of Hong Kong Literature,” Li Tuo’s “Resistance to Modernity: Reflections on Mainland Chinese Literary Criticism in the 1980s,” and Michelle Yeh’s “Death of the Poet: Poetry and Society in Contemporary China and Taiwan” first ap- peared in the special issue “Contemporary Chinese Literature: Crossing the Bound- aries” (edited by Yvonne Chang) of Literature East and West (1995). Jeffrey Kinkley’s “A Bibliographic Survey of Publications on Chinese Literature in Translation from 1949 to 1999” first appeared in Choice (April 1994; copyright by the American Library Associ- ation). All of the essays have been revised for this volume. This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by David D. W. Wang All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

The Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun Wei-Yi Lee University of Colorado Boulder, [email protected]

University of Colorado, Boulder CU Scholar Comparative Literature Graduate Theses & Comparative Literature Dissertations Summer 7-18-2014 Psychoanalyzed Vacillation between and Entanglement of the Old and the New in 1930s Shanghai: the Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun Wei-Yi Lee University of Colorado Boulder, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.colorado.edu/coml_gradetds Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Wei-Yi, "Psychoanalyzed Vacillation between and Entanglement of the Old and the New in 1930s Shanghai: the Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun" (2014). Comparative Literature Graduate Theses & Dissertations. Paper 3. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Comparative Literature at CU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Literature Graduate Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CU Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Psychoanalyzed Vacillation between and Entanglement of the Old and the New in 1930s Shanghai: the Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun by WEI-YI LEE B.A., National Taiwan University, 2005 M.A., National Chengchi University, 2008 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Comparative Literature Graduate Program 2014 This thesis entitled: Psychologized Vacillation between and Entanglement of the Old and the New in 1930s Shanghai: the Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun written by Wei-Yi Lee has been approved for Comparative Literature Graduate Program Chair: Dr. -

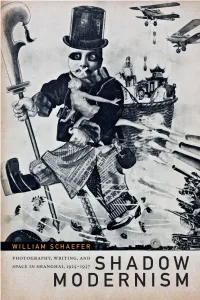

Read the Introduction

William Schaefer PhotograPhy, Writing, and SPace in Shanghai, 1925–1937 Duke University Press Durham and London 2017 © 2017 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Text designed by Mindy Basinger Hill Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schaefer, William, author. Title: Shadow modernism : photography, writing, and space in Shanghai, 1925–1937 / William Schaefer. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and ciP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017007583 (print) lccn 2017011500 (ebook) iSbn 9780822372523 (ebook) iSbn 9780822368939 (hardcover : alk. paper) iSbn 9780822369196 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcSh: Photography—China—Shanghai—History—20th century. | Modernism (Art)—China—Shanghai. | Shanghai (China)— Civilization—20th century. Classification: lcc tr102.S43 (ebook) | lcc tr102.S43 S33 2017 (print) | ddc 770.951/132—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007583 Cover art: Biaozhun Zhongguoren [A standard Chinese man], Shidai manhua (1936). Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University Libraries. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the University of Rochester, Department of Modern Languages and Cultures and the College of Arts, Sciences, and Engineering, which provided funds toward the publication -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Dreams and disillusionment in the City of Light : Chinese writers and artists travel to Paris, 1920s-1940s Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/07g4g42m Authors Chau, Angie Christine Chau, Angie Christine Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Dreams and Disillusionment in the City of Light: Chinese Writers and Artists Travel to Paris, 1920s–1940s A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Angie Christine Chau Committee in charge: Professor Yingjin Zhang, Chair Professor Larissa Heinrich Professor Paul Pickowicz Professor Meg Wesling Professor Winnie Woodhull Professor Wai-lim Yip 2012 Signature Page The Dissertation of Angie Christine Chau is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ...................................................................................................................iii Table of Contents............................................................................................................... iv List of Illustrations.............................................................................................................. v Acknowledgements........................................................................................................... -

Purity, Modernity, and Pessimism :: Translation of Mu Shiying's Fiction/ Rui Tao University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2000 Purity, modernity, and pessimism :: translation of Mu Shiying's fiction/ Rui Tao University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Tao, Rui, "Purity, modernity, and pessimism :: translation of Mu Shiying's fiction/" (2000). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2024. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2024 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PURITY, MODERNITY, AND PESSIMISM TRANSLATION OF MU SHIYING'S FICTION A Thesis Presented by RUI TAO Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 2000 Department of Asian Languages and Literatures PURITY, MODERNITY, AND PESSIMISM TRANSLATION OF MU SHIYING'S FICTION A Thesis Presented by RUI TAO Approved as to style and content by Donald Gjertson, Chair DpfisJBargen, Member YaohuajShi, Member 0 Chisato Kitagawa, Department head Department of Asian language & Literatures ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to members of the committee, Dr. Donald Gjertson, Dr. Doris Bargen and Dr. Yaohua Shi, for their patient guidance and support. I would also like to thank my American sister, Lindsley Cameron, who took time to read the manuscript and provided valuable feedback on it. Finally, I would like to thank my parents, my sister and my brother for then- priceless support. -

University of California

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Performing Perversion: Decadence in Twentieth-Century Chinese Literature Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/89r2b0jj Author Wang, Hongjian Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Performing Perversion: Decadence in Twentieth-Century Chinese Literature A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Hongjian Wang September 2012 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Perry Link, Chairperson Dr. Paul Pickowicz Dr. Susan Zieger Copyright by Hongjian Wang 2012 The Dissertation of Hongjian Wang is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements This dissertation is the result of an academic adventure that is deeply indebted to the guidance of all my three committee members. Dr. Susan Zieger ushered me into the world of Western Decadence in the late nineteenth century. Dr. Paul Pickowicz instilled into me a strong interest in and the methodology of cultural history studies. Dr. Perry Link guided me through the palace of twentieth-century Chinese literature and encouraged me to study Decadence in modern Chinese literature in comparison with Western Decadence combining the methodology of literary studies and cultural history studies. All of them have been extremely generous in offering me their valuable advices from their expertise, which made this adventure eye-opening and spiritually satisfying. My special gratitude goes to Dr. Link. His broad knowledge and profound understanding of Chinese literature and society, his faith in and love of seeking the truth, and his concern about the fate of ordinary people are inexhaustible sources of inspiration to me. -

Liu Na'ou's Modernist Writings Travelling Across East Asia

Between the National and Cosmopolitan: Liu Na’ou’s Modernist Writings Travelling across East Asia Ying Xiong In 1926,1 a young Taiwanese man travelled to Shanghai to learn French in the Jesuit Université L’Aurore (上海震旦大学).2 He had just graduated from the English department at Aoyama Gakuin University (青山学院) in Tokyo.3 He was greatly influenced by the French writer Paul Morand (1888-1976) and the Japanese movement of Neo-Sensationalism (新感覚派). This young Taiwanese man was Liu Na’ou (刘呐鸥 1905-1940) who became one of the founders of Neo-Sensationalism in China.4 Liu was born in Taiwan in 1905 and moved to Tokyo in 1920 to pursue his high school and university education. After his mother refused his request to study in France following his graduation, Liu travelled to Shanghai to learn French. In Shanghai, he published a collection of short stories titled City Scenery (都市风景线) in 1930. The popularity of the book made him one of China’s first modernist writers. In his short life, Liu travelled across four 1 The exact year in which Liu went to Shanghai was uncertain. In Shu-mei Shih’s study, The Lure of the Modern: Writing Modernism in Semicolonial China, 1917–1937 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), Liu went to the Jesuit Université L’Aurore in 1924. 2 Xiaoyan Peng, ‘Liu Na’ou 1927 nian riji’ (Liu Na’ou’s Diary of 1927), in Reading, no. 10 (1998), pp.134–142. 3 I have used Pinyin and Hepburn Romanisation for Chinese and Japanese terms respectively. In both languages exceptions are made for words and place names that are familiarly used in English, such as Tokyo and Kuomintang. -

Liu Na'ou's Chinese Modernist Writing in the East Asian Context

www.ccsenet.org/ach Asian Culture and History Vol. 3, No. 1; January 2011 Ethno Literary Identity and Geographical Displacement: Liu Na'ou's Chinese Modernist Writing in the East Asian Context Ying Xiong School of Languages and Cultures The University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In the course of his short literary life, Liu Na'ou travelled across four geographical areas: Taiwan, Japan, Shanghai and Beijing, as well as five cultural domains: Taiwanese, Japanese, French, English and Chinese. The transnational facet of Liu's modernist writing is not merely literary or cultural but political and historical. The earliest modernist writing in China was initiated on the basis of the colonial experience of Taiwan and the semi-colonial modernity of Shanghai. It became a “contact zone” in which various cultural and political influences to contest with each other, signaling a process of power shifting in East Asia in the early 20th century. This article aims to reflect on theoretical issues ranging from nationalism, cosmopolitanism, colonialism and semi-colonialism, to the colonial modernity of East Asia, drawing upon Liu's modernist writings in 1928. Keywords: Liu Na'ou, Chinese modernist writing, Semi-colonialism, Intertwined colonization 1. Introduction In 1926, a young Taiwanese man named Liu Na'ou (1905–1940) travelled to Shanghai to study the French language at the Jesuit Université L'Aurore (Note 1), having earlier graduated from the English department at Aoyama Gakuin University (Note 2) in Tokyo (Peng, 1998, p.134). Influenced by French writer Paul Morand (1888–1976) and by Japanese Neo-Sensationalism, this young Taiwanese was later to become one of the founders of Chinese modernist literature (Note 3). -

The Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis

Psychoanalyzed Vacillation between and Entanglement of the Old and the New in 1930s Shanghai: the Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun by WEI-YI LEE B.A., National Taiwan University, 2005 M.A., National Chengchi University, 2008 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Comparative Literature Graduate Program 2014 This thesis entitled: Psychologized Vacillation between and Entanglement of the Old and the New in 1930s Shanghai: the Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun written by Wei-Yi Lee has been approved for Comparative Literature Graduate Program Chair: Dr. Eric C. White Committee Member: Dr. Faye Yuan Kleeman Committee Member: Dr. G. Andrew Stuckey Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Lee, Wei-Yi (MA., Comparative Literature) Psychologized Vacillation between and Entanglement of the Old and the New in 1930s Shanghai: the Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun Thesis directed by Assistant Professor G. Andrew Stuckey Shi Zhecun 施蟄存 (1905-2003), an avant-garde modernist writer in 1930s Shanghai, claimed that his works “were influenced [by Sigmund Freud (1856-1939)], while breaking away from the influence.” That is to say, Freudian psychoanalysis was Sinicized (i.e. became influenced by Chinese thought or culture) in Shi Zhecun’s fiction writing. -

Kang-I Sun Chang (孫康宜), the Inaugural Malcolm G. Chace

CURRICULUM VITAE Kang-i Sun Chang 孫 康 宜 Kang-I Sun Chang: Short Bio Kang-i Sun Chang (孫康宜), the inaugural Malcolm G. Chace ’56 Professor of East Asian Languages and Literatures at Yale University, is a scholar of classical Chinese literature, with an interest in literary criticism, comparative studies of poetry, gender studies, and cultural theory/aesthetics. The Chace professorship was established by Malcolm “Kim” G. Chace III ’56, “to support the teaching and research activities of a full-time faculty member in the humanities, and to further the University’s preeminence in the study of arts and letters.” Chang is the author of The Evolution of Chinese Tz’u Poetry: From Late Tang to Northern Sung; Six Dynasties Poetry; The Late Ming Poet Ch’en Tzu-lung: Crises of Love and Loyalism; and Journey Through the White Terror. She is the co-editor of Writing Women in Late Imperial China (with Ellen Widmer), Women Writers of Traditional China (with Haun Saussy), and The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature (with Stephen Owen). Her translations have been published in a number of Chinese publications, and she has also authored books in Chinese, including Wenxue jingdian de tiaozhan (Challenges of the Literary Canon), Wenxue de shengyin (Voices of Literature), Zhang Chonghe tizi xuanji (Calligraphy of Ch’ung-ho Chang Frankel: Selected Inscriptions), Quren hongzhao (Artistic and Cultural Traditions of the Kunqu Musicians), and Wo kan Meiguo jingshen (My Thoughts on the American Spirit). Her current book project is tentatively titled, “Shi Zhecun: A Modernist Turned Classicist.” At Yale, Chang is on the affiliated faculty of the Department of Comparative Literature and is also on the faculty associated with the Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Program. -

Women Stereotypes in Shi Zhecun's Short Stories

Edinburgh Research Explorer Women Stereotypes in Shi Zhecun's Short Stories Citation for published version: Rosenmeier, C 2011, 'Women Stereotypes in Shi Zhecun's Short Stories', Modern china, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 44-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0097700410384575 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1177/0097700410384575 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Modern china General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 Modern China http://mcx.sagepub.com/ Women Stereotypes in Shi Zhecun's Short Stories Christopher Rosenmeier Modern China 2011 37: 44 originally published online 20 December 2010 DOI: 10.1177/0097700410384575 The online version of this article can be found at: http://mcx.sagepub.com/content/37/1/44 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Modern China can be found at: Email