Purity, Modernity, and Pessimism :: Translation of Mu Shiying's Fiction/ Rui Tao University of Massachusetts Amherst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modernism in Practice: Shi Zhecun's Psychoanalytic Fiction Writing

Modernism in Practice: Shi Zhecun's Psychoanalytic Fiction Writing Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Zhu, Yingyue Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 14:07:54 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/642043 MODERNISM IN PRACTICE: SHI ZHECUN’S PSYCHOANALYTIC FICTION WRITING by Yingyue Zhu ____________________________ Copyright © Yingyue Zhu 2020 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Master’s Committee, we certify that we have read the thesis prepared by Yingyue Zhu, titled MODERNISM IN PRACTICE: SHI ZHECUN’S PSYCHOANALYTIC FICTION WRITING and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Master’s Degree. Jun 29, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Dian Li Fabio Lanza Jul 2, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Fabio Lanza Jul 2, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Scott Gregory Final approval and acceptance of this thesis is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the thesis to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this thesis prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the Master’s requirement. -

The New Sensationists

Edinburgh Research Explorer The new sensationists Citation for published version: Rosenmeier, C 2018, The new sensationists: Shi Zhecun, Mu Shiying, Liu Na'ou. in MD Gu (ed.), The Routledge Companion of Modern Chinese Literature. 1 edn, Routledge, pp. 168-180. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: The Routledge Companion of Modern Chinese Literature Publisher Rights Statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge in Routledge Handbook of Modern Chinese Literature on 3/09/2018, available online: https://www.routledge.com/Routledge-Handbook-of-Modern- Chinese-Literature/Gu/p/book/9781138647541 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 The New Sensationists: Shi Zhecun, Mu Shiying, and Liu Na’ou, Introduction The three writers under consideration here—Shi Zhecun (1905–2003), Mu Shiying (1912– 1940), and Liu Na’ou (1905–1940)—were the foremost modernist authors in the Republican period. Collectively labelled “New Sensationists” (xinganjuepai), they were mainly active in Shanghai in the early 1930s, and their most famous works reflect the speed, chaos, and intensity of the metropolis.1 They wrote about dance halls, neon lights, and looming madness alongside modern lifestyles, gender roles, and social problems. -

Notes Made in China in May 1990 for the BBC Radio Documentary *The Urgent Knocking: New Chinese Writing and the Movement for Democracy* Gregory B

Notes made in China in May 1990 for the BBC radio documentary *The Urgent Knocking: New Chinese Writing and the Movement for Democracy* Gregory B. Lee To cite this version: Gregory B. Lee. Notes made in China in May 1990 for the BBC radio documentary *The Urgent Knocking: New Chinese Writing and the Movement for Democracy*. 2019. hal-02196338 HAL Id: hal-02196338 https://hal-univ-lyon3.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02196338 Preprint submitted on 28 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Gregory B. Lee. URGENT KNOCKING, China/Hong Kong Notebook, May 1990. Notes made in China in May 1990 in connection with the hour-long radio documentary The Urgent Knocking: New Chinese Writing and the Movement for Democracy which I was making for the BBC and which was broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on 4the June 1990 to coincide with the 1st anniversary of the massacre at Tiananmen. My Urgent Knocking notebook is somewhat cryptic. I was worried about prying eyes, and the notes were not made in chronological, or consecutive order, but scattered throughout my notebook. Probably, I was hoping that their haphazard pagination would withstand a cursory inspection. -

Gregory Lee CV 1

Gregory Lee CV Curriculum vitae GREGORY B. LEE 利大英 Professor of Chinese and Transcultural Studies, Université de Lyon – Jean Moulin (since 1999) Director, Institut d’Etudes Transtextuelles et Transculturelles (Institute for Transtextual and Transcultural Studies — IETT) Fellow of the Hong Kong Academy of the Humanities Chevalier de l’ordre des Palmes académiques Nationalities: British & French Languages: English (native), Chinese (near native), French (near native); Spanish (good); Portuguese, Italian (reading) PREVIOUS AND VISITING POSTS 05.2018 ; 03.2019 Visiting Professor, Sun Yat-sen University, Canton, China 2010-2012 Chair Professor of Chinese & Transcultural Studies, City University of Hong Kong Founding Director, Hong Kong Advanced Institute for Cross-Disciplinary Studies 2005-2010 Honorary Visiting Professor, University of Wuhan, China 1998-1999 Visiting Professor, University of Lyon (Jean Moulin) 1994-1998 Associate Professor, Department of Comparative Literature, University of Hong Kong 1990-1994 Assistant Professor, East Asian Languages & Civilizations, University of Chicago 1987-1988 Lecturer (temporary), Department of East Asia School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 1983-1984 Supervisor, Faculty of Oriental Studies Cambridge University OTHER PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 1988-1990 Asia Specialist (report writer and broadcaster), BBC World Service 1986-1987 Editor, Foreign Languages Press (SINOLINGUA Chinese as a second language), Beijing 1983-1984 Acting Head, Far Eastern Library, Cambridge University 1 Gregory -

Chinese Literature in the Second Half of a Modern Century: a Critical Survey

CHINESE LITERATURE IN THE SECOND HALF OF A MODERN CENTURY A CRITICAL SURVEY Edited by PANG-YUAN CHI and DAVID DER-WEI WANG INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS • BLOOMINGTON AND INDIANAPOLIS William Tay’s “Colonialism, the Cold War Era, and Marginal Space: The Existential Condition of Five Decades of Hong Kong Literature,” Li Tuo’s “Resistance to Modernity: Reflections on Mainland Chinese Literary Criticism in the 1980s,” and Michelle Yeh’s “Death of the Poet: Poetry and Society in Contemporary China and Taiwan” first ap- peared in the special issue “Contemporary Chinese Literature: Crossing the Bound- aries” (edited by Yvonne Chang) of Literature East and West (1995). Jeffrey Kinkley’s “A Bibliographic Survey of Publications on Chinese Literature in Translation from 1949 to 1999” first appeared in Choice (April 1994; copyright by the American Library Associ- ation). All of the essays have been revised for this volume. This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by David D. W. Wang All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

Two Poems Chen Li Translated by Elaine Wong

Special Focus Chinese Contemporary Poetry Two Poems Chen Li Translated by Elaine Wong The two poems included here are from Elaine Wong’s project translating Chen Li’s poetry. “I Run into Monet in Monet’s Garden” imagines a conversation with Monet on the redemptive power of art in times of personal suffering. Wong’s recent viewing of the wall-sized Water Lilies by Monet at the Met brought some breakthroughs to this translation, especially to the wordplay on “water lily” and to the transition from pain to beauty. “Rivers North of the Future” portrays Chen Li’s friendship with the Beijing poet Wang Jiaxin as well as his aspiration for sincere poetic exchanges between Taiwan and mainland China. Meeting both poets in summer 2018 helped Wong better understand the poets’ relationship and their poems. CHINESE LITERATURE TODAY VOL . 8 NO . 1 97 I Run into Monet in Monet’s Garden I run into Monet in Monet’s Garden. He asks, “Did But your eyesight is deteriorating. (Is there you come a cataract?) from the Orangerie, where lianhua ponds line the Can you see light sharply with your eyes? oval walls?” “I also use my mind’s eye. I can see I say, I came from Hualien, the opposite direction. the wrinkles in flowing water. That Your is immortal youth . ” Japanese footbridge brought me here. You came up I came under physical and emotional pain, against and encountered a depression as heavy, or light, poverty, and you lost two wives and your eldest son as ocean and sky blue. Can I turn Hualien, my in his prime. -

The Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun Wei-Yi Lee University of Colorado Boulder, [email protected]

University of Colorado, Boulder CU Scholar Comparative Literature Graduate Theses & Comparative Literature Dissertations Summer 7-18-2014 Psychoanalyzed Vacillation between and Entanglement of the Old and the New in 1930s Shanghai: the Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun Wei-Yi Lee University of Colorado Boulder, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.colorado.edu/coml_gradetds Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Wei-Yi, "Psychoanalyzed Vacillation between and Entanglement of the Old and the New in 1930s Shanghai: the Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun" (2014). Comparative Literature Graduate Theses & Dissertations. Paper 3. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Comparative Literature at CU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Literature Graduate Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CU Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Psychoanalyzed Vacillation between and Entanglement of the Old and the New in 1930s Shanghai: the Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun by WEI-YI LEE B.A., National Taiwan University, 2005 M.A., National Chengchi University, 2008 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Comparative Literature Graduate Program 2014 This thesis entitled: Psychologized Vacillation between and Entanglement of the Old and the New in 1930s Shanghai: the Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun written by Wei-Yi Lee has been approved for Comparative Literature Graduate Program Chair: Dr. -

GÉRALDINE A. FISS (許潔琳), Ph.D

Updated July 16, 2020 GÉRALDINE A. FISS (許潔琳), Ph.D. East Asian Languages and Cultures University of Southern California Taper Hall of Humanities, 356E Los Angeles, CA 90089-0357 [email protected] ACADEMIC POSITIONS Scholar in Residence, 2020 – present. University of Southern California Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures. Lecturer, 2015 - 2020. University of Southern California Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures. Postdoctoral Research Associate, 2010 - 2015. University of Southern California Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures. EDUCATION Harvard University, Ph.D. East Asian Languages and Civilizations (2008) Concentration Fields: Modern Chinese Literature, Intellectual History and Film; Late Imperial Chinese Literature and Thought; Tokugawa and Meiji Japanese History and Thought Dissertation: Textual Travels and Traveling Texts: Tracing Encounters with German Culture, Literature and Thought in Late Qing and Early Republican China. Dissertation Advisers: Professor David Wang, Professor Wilt Idema, Professor Wai-yee Li Smith College, B.A. East Asian Languages and Literatures, cum laude with highest honors (1997) Major: East Asian Languages and Literatures Minor: German Literature and Culture Studies LANGUAGES Mandarin Chinese: advanced level of fluency Modern Japanese: intermediate level of fluency Classical Chinese and Latin: reading knowledge English, German, French and Swedish: native fluency RESEARCH INTERESTS Transcultural Intertextuality in Modern and Contemporary Chinese Poetics, Literature and Film Chinese-German, East-West, and Sino-Japanese Literary, Aesthetic and Cinematic Relations Chinese Women’s Literature, Cinema and Thought Chinese Dissident Poetry, Fiction and Film The Fantastic in East Asian Literature and Film Chinese and East Asian Ecocriticism, Ecopoetry and Ecocinema JOURNAL ARTICLES AND BOOK CHAPTERS Fiss, Géraldine. -

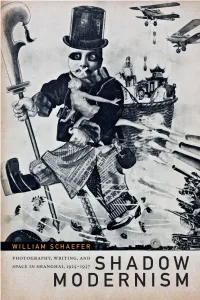

Read the Introduction

William Schaefer PhotograPhy, Writing, and SPace in Shanghai, 1925–1937 Duke University Press Durham and London 2017 © 2017 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Text designed by Mindy Basinger Hill Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schaefer, William, author. Title: Shadow modernism : photography, writing, and space in Shanghai, 1925–1937 / William Schaefer. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and ciP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017007583 (print) lccn 2017011500 (ebook) iSbn 9780822372523 (ebook) iSbn 9780822368939 (hardcover : alk. paper) iSbn 9780822369196 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcSh: Photography—China—Shanghai—History—20th century. | Modernism (Art)—China—Shanghai. | Shanghai (China)— Civilization—20th century. Classification: lcc tr102.S43 (ebook) | lcc tr102.S43 S33 2017 (print) | ddc 770.951/132—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007583 Cover art: Biaozhun Zhongguoren [A standard Chinese man], Shidai manhua (1936). Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University Libraries. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the University of Rochester, Department of Modern Languages and Cultures and the College of Arts, Sciences, and Engineering, which provided funds toward the publication -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Dreams and disillusionment in the City of Light : Chinese writers and artists travel to Paris, 1920s-1940s Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/07g4g42m Authors Chau, Angie Christine Chau, Angie Christine Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Dreams and Disillusionment in the City of Light: Chinese Writers and Artists Travel to Paris, 1920s–1940s A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Angie Christine Chau Committee in charge: Professor Yingjin Zhang, Chair Professor Larissa Heinrich Professor Paul Pickowicz Professor Meg Wesling Professor Winnie Woodhull Professor Wai-lim Yip 2012 Signature Page The Dissertation of Angie Christine Chau is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ...................................................................................................................iii Table of Contents............................................................................................................... iv List of Illustrations.............................................................................................................. v Acknowledgements........................................................................................................... -

The University of Chicago Sound Images, Acoustic

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO SOUND IMAGES, ACOUSTIC CULTURE, AND TRANSMEDIALITY IN 1920S-1940S CHINESE CINEMA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DEVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY LING ZHANG CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2017 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………………iii Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………. x Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter One Sound in Transition and Transmission: The Evocation and Mediation of Acoustic Experience in Two Stars in the Milky Way (1931) ...................................................................................................................................................... 20 Chapter Two Metaphoric Sound, Rhythmic Movement, and Transcultural Transmediality: Liu Na’ou and The Man Who Has a Camera (1933) …………………………………………………. 66 Chapter Three When the Left Eye Meets the Right Ear: Cinematic Fantasia and Comic Soundscape in City Scenes (1935) and 1930s Chinese Film Sound… 114 Chapter Four An Operatic and Poetic Atmosphere (kongqi): Sound Aesthetic and Transmediality in Fei Mu’s Xiqu Films and Spring in a Small Town (1948) … 148 Filmography…………………………………………………………………………………………… 217 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………………… 223 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Over the long process of bringing my dissertation project to fruition, I have accumulated a debt of gratitude to many gracious people who have made that journey enjoyable and inspiring through the contribution of their own intellectual vitality. First and foremost, I want to thank my dissertation committee for its unfailing support and encouragement at each stage of my project. Each member of this small group of accomplished scholars and generous mentors—with diverse personalities, academic backgrounds and critical perspectives—has nurtured me with great patience and expertise in her or his own way. I am very fortunate to have James Lastra as my dissertation co-chair. -

Literature and the Pictorial Magazine

Chapter 1 Literature and the Pictorial Magazine An Introduction to Writers and Writings in Wenyi and Wanxiang The short-lived magazines Wenyi and Wanxiang were just two of many dedicated to the latest movements in art and literature that appeared in 1934, an unprecedented year for the Shanghai magazine publishing industry that became known as The Year of the Magazine.1 The magazines included essays on art and literature from Europe, America, and Japan, with short sto- ries by Chinese writers and translations into Chinese of writings by foreign authors. Ye Lingfeng 葉靈鳳 (1905–1975) and Mu Shiying, both associated with the New-sensationist group of writers (Mu as a central figure and Ye on its fringes) were the chief editors of Wenyi, a magazine described by their col- league Hei Ying in later years as a ‘pure art and literature publication’, in other words a magazine dedicated to ‘art for art’s sake’.2 The products of the writ- ers associated with this group consciously adopted traits of the writing of the Shinkankaku-ha, the Japanese New-sensationists, whose work had been intro- duced to China by Liu Na’ou in the 1920s, as well as aspects of the writings of the French modernist Paul Morand (1888–1976), who had already been such an inspiration to the Japanese group in the early part of that decade.3 In common with many other writers and artists in Shanghai during the 1930s, one of the aims of these Chinese writers was to break down barriers that were seen to exist between ‘high’ and ‘low’ cultures, with the result that their work takes on many of the trappings of popular cultural imagery, while at the same time retaining what might be described as its ‘avant-garde’, modern- ist nature.