The Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modernism in Practice: Shi Zhecun's Psychoanalytic Fiction Writing

Modernism in Practice: Shi Zhecun's Psychoanalytic Fiction Writing Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Zhu, Yingyue Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 14:07:54 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/642043 MODERNISM IN PRACTICE: SHI ZHECUN’S PSYCHOANALYTIC FICTION WRITING by Yingyue Zhu ____________________________ Copyright © Yingyue Zhu 2020 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Master’s Committee, we certify that we have read the thesis prepared by Yingyue Zhu, titled MODERNISM IN PRACTICE: SHI ZHECUN’S PSYCHOANALYTIC FICTION WRITING and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Master’s Degree. Jun 29, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Dian Li Fabio Lanza Jul 2, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Fabio Lanza Jul 2, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Scott Gregory Final approval and acceptance of this thesis is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the thesis to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this thesis prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the Master’s requirement. -

The New Sensationists

Edinburgh Research Explorer The new sensationists Citation for published version: Rosenmeier, C 2018, The new sensationists: Shi Zhecun, Mu Shiying, Liu Na'ou. in MD Gu (ed.), The Routledge Companion of Modern Chinese Literature. 1 edn, Routledge, pp. 168-180. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: The Routledge Companion of Modern Chinese Literature Publisher Rights Statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge in Routledge Handbook of Modern Chinese Literature on 3/09/2018, available online: https://www.routledge.com/Routledge-Handbook-of-Modern- Chinese-Literature/Gu/p/book/9781138647541 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 The New Sensationists: Shi Zhecun, Mu Shiying, and Liu Na’ou, Introduction The three writers under consideration here—Shi Zhecun (1905–2003), Mu Shiying (1912– 1940), and Liu Na’ou (1905–1940)—were the foremost modernist authors in the Republican period. Collectively labelled “New Sensationists” (xinganjuepai), they were mainly active in Shanghai in the early 1930s, and their most famous works reflect the speed, chaos, and intensity of the metropolis.1 They wrote about dance halls, neon lights, and looming madness alongside modern lifestyles, gender roles, and social problems. -

Chinese Literature in the Second Half of a Modern Century: a Critical Survey

CHINESE LITERATURE IN THE SECOND HALF OF A MODERN CENTURY A CRITICAL SURVEY Edited by PANG-YUAN CHI and DAVID DER-WEI WANG INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS • BLOOMINGTON AND INDIANAPOLIS William Tay’s “Colonialism, the Cold War Era, and Marginal Space: The Existential Condition of Five Decades of Hong Kong Literature,” Li Tuo’s “Resistance to Modernity: Reflections on Mainland Chinese Literary Criticism in the 1980s,” and Michelle Yeh’s “Death of the Poet: Poetry and Society in Contemporary China and Taiwan” first ap- peared in the special issue “Contemporary Chinese Literature: Crossing the Bound- aries” (edited by Yvonne Chang) of Literature East and West (1995). Jeffrey Kinkley’s “A Bibliographic Survey of Publications on Chinese Literature in Translation from 1949 to 1999” first appeared in Choice (April 1994; copyright by the American Library Associ- ation). All of the essays have been revised for this volume. This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by David D. W. Wang All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

The Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun Wei-Yi Lee University of Colorado Boulder, [email protected]

University of Colorado, Boulder CU Scholar Comparative Literature Graduate Theses & Comparative Literature Dissertations Summer 7-18-2014 Psychoanalyzed Vacillation between and Entanglement of the Old and the New in 1930s Shanghai: the Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun Wei-Yi Lee University of Colorado Boulder, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.colorado.edu/coml_gradetds Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Wei-Yi, "Psychoanalyzed Vacillation between and Entanglement of the Old and the New in 1930s Shanghai: the Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun" (2014). Comparative Literature Graduate Theses & Dissertations. Paper 3. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Comparative Literature at CU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Literature Graduate Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CU Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Psychoanalyzed Vacillation between and Entanglement of the Old and the New in 1930s Shanghai: the Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun by WEI-YI LEE B.A., National Taiwan University, 2005 M.A., National Chengchi University, 2008 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Comparative Literature Graduate Program 2014 This thesis entitled: Psychologized Vacillation between and Entanglement of the Old and the New in 1930s Shanghai: the Sinicization of Freudian Psychoanalysis in Two Short Stories by Shi Zhecun written by Wei-Yi Lee has been approved for Comparative Literature Graduate Program Chair: Dr. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Name Stephen Anthony SMITH Address All Souls

CURRICULUM VITAE Name Stephen Anthony SMITH Address All Souls College University of Oxford 27 High Street Oxford OX1 4AL United Kingdom Phone: 0044- (0)1865-279343 University Positions 1977 - Lecturer, Department of History, University of Essex. 1984 - Senior Lecturer " " 1991- Professor " " 2008-12 Professor of Comparative History, European University Institute, Florence. 2012-19 Senior Research Fellow, All Souls College, Oxford. 2019- Emeritus Fellow, All Souls College, Oxford. 2012- Associate of the China Centre, University of Oxford 2013 - Professor of History, University of Oxford 2018 - Visiting Professor, History Faculty, Peking University University Education 1970-73: Open Scholar in Modern History, Oriel College, Oxford. 1973: BA (Hons) in Modern History 1973-4: MSocSci in Soviet Studies, Centre for Russian and East European Studies, University of Birmingham. 1976-77: University of Moscow, Faculty of History. British Council exchange student. 1980: PhD, University of Birmingham. Winner of Ashley Prize. 1982-3 Certificate in Advanced Studies in Contemporary Chinese, Beijing Languages Institute (Sept. 1982-Jan. 1983); Peking University, Faculty of History (Jan-July 1983). Academic Awards and Distinctions - Visiting Professor, History Department, Central European University, Budapest, May 2019 - Honorary Fellow, Oriel College, Oxford: 2018 - 1 - Visiting Professor History Faculty, Peking University, September-December 2018 - Visiting Fellow, Academia Sinica, Taiwan, December 2018 - Vice-Chair Past and Present Editorial Board, 2018- - Fellow of the British Academy, 2014 - - Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, 1995- - British Academy Research Leave Fellowship, 2006-08 - Fellow at the International Center for Advanced Studies, New York University. Project on the Cold War as Global Conflict. Jan-May, 2004. - One-month visit to China under British Academy/ESRC and Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Exchange (September 2001) - Wiles Lecturer, Queen’s University, Belfast (1998), 2014-18. -

Read the Introduction

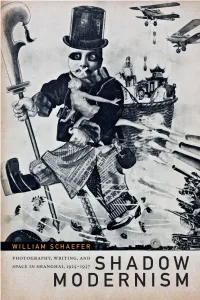

William Schaefer PhotograPhy, Writing, and SPace in Shanghai, 1925–1937 Duke University Press Durham and London 2017 © 2017 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Text designed by Mindy Basinger Hill Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schaefer, William, author. Title: Shadow modernism : photography, writing, and space in Shanghai, 1925–1937 / William Schaefer. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and ciP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017007583 (print) lccn 2017011500 (ebook) iSbn 9780822372523 (ebook) iSbn 9780822368939 (hardcover : alk. paper) iSbn 9780822369196 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcSh: Photography—China—Shanghai—History—20th century. | Modernism (Art)—China—Shanghai. | Shanghai (China)— Civilization—20th century. Classification: lcc tr102.S43 (ebook) | lcc tr102.S43 S33 2017 (print) | ddc 770.951/132—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007583 Cover art: Biaozhun Zhongguoren [A standard Chinese man], Shidai manhua (1936). Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University Libraries. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the University of Rochester, Department of Modern Languages and Cultures and the College of Arts, Sciences, and Engineering, which provided funds toward the publication -

Current Thinking and Liberal Arts Education in China

Current Thinking and Liberal Arts Education in China Author: Youguo Jiang Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104094 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2013 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College Lynch School of Education Department of Education Administration and Higher Education Current Thinking and Liberal Arts Education in China You Guo Jiang, S. J. Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2, 2013 © copyright by YOU GUO JIANG 2013 Conceptions about Liberal Arts Education in China Abstract Liberal arts education is an emerging phenomenon in China. However, under the pressure of exam-oriented education, memorization, and lecture pedagogy, faculty, university administrators and policy makers have not embraced it whole-heartedly. Through qualitative methodology, this study explores the current thinking of Chinese policy makers, university administrators, and faculty members on liberal arts education and its challenges. A study of the perceptions of 96 Chinese government and university administrators and faculty members regarding liberal arts education through document analysis and interviews at three universities helps in comprehending the process of an initiative in educational policy in contemporary Chinese universities. This research analyzes Chinese policy making at the institutional and national levels on curriculum reform with particular emphasis on the role of education in shaping well-rounded global citizens, and it examines how the revival of liberal arts education in China would produce college graduates with the creativity, critical thinking, moral reasoning, innovation and cognitive complexity needed for social advancement and personal integration in a global context. -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Dreams and disillusionment in the City of Light : Chinese writers and artists travel to Paris, 1920s-1940s Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/07g4g42m Authors Chau, Angie Christine Chau, Angie Christine Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Dreams and Disillusionment in the City of Light: Chinese Writers and Artists Travel to Paris, 1920s–1940s A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Angie Christine Chau Committee in charge: Professor Yingjin Zhang, Chair Professor Larissa Heinrich Professor Paul Pickowicz Professor Meg Wesling Professor Winnie Woodhull Professor Wai-lim Yip 2012 Signature Page The Dissertation of Angie Christine Chau is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ...................................................................................................................iii Table of Contents............................................................................................................... iv List of Illustrations.............................................................................................................. v Acknowledgements........................................................................................................... -

Purity, Modernity, and Pessimism :: Translation of Mu Shiying's Fiction/ Rui Tao University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2000 Purity, modernity, and pessimism :: translation of Mu Shiying's fiction/ Rui Tao University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Tao, Rui, "Purity, modernity, and pessimism :: translation of Mu Shiying's fiction/" (2000). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2024. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2024 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PURITY, MODERNITY, AND PESSIMISM TRANSLATION OF MU SHIYING'S FICTION A Thesis Presented by RUI TAO Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 2000 Department of Asian Languages and Literatures PURITY, MODERNITY, AND PESSIMISM TRANSLATION OF MU SHIYING'S FICTION A Thesis Presented by RUI TAO Approved as to style and content by Donald Gjertson, Chair DpfisJBargen, Member YaohuajShi, Member 0 Chisato Kitagawa, Department head Department of Asian language & Literatures ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to members of the committee, Dr. Donald Gjertson, Dr. Doris Bargen and Dr. Yaohua Shi, for their patient guidance and support. I would also like to thank my American sister, Lindsley Cameron, who took time to read the manuscript and provided valuable feedback on it. Finally, I would like to thank my parents, my sister and my brother for then- priceless support. -

1. Academic Curriculum Vitae...3

Charles RAMOND Professional Page TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. ACADEMIC CURRICULUM VITAE ..................................................... 3 Current Functions .................................................................................................... 3 Synthetic Curriculum Vitae ....................................................................................... 3 Collective Responsibilities ........................................................................................ 3 Component Directorates....................................................................................... 3 Directorates of Research Structures .................................................................... 4 Responsibilities Hold in National Agencies........................................................... 4 Organization of Seminars, Colloquiums, Conferences ......................................... 4 Doctoral and Research Supervision Award / Scientific Excellence Award ........... 4 2. PERSONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................. 5 Synthetic Table ........................................................................................................ 5 Books (13) ................................................................................................................ 5 Edited Books (14) .................................................................................................... 6 Articles in Peer Reviewed Journals (31) ................................................................ 10 -

East China University of Science and Technology (ECUST) Located In

East China University of Science and Technology (ECUST) Located in the southwest of Shanghai, a center of commerce, finance, culture and industrial production of China, East China University of Science and Technology is a dynamic and prominent research-intensive university with high teaching quality. ECUST is comprised of more than 1.7 million square meters on 3 campuses. The main campus, being 17 kilometers from Hongqiao Airport and 45 kilometers from Pudong International Airport, is situated in the prosperous and energetic Xuhui District. In addition to its downtown location, the university also features two other campuses in Fengxian and Jinshan District. The history of education of the university can be dated back to Nanyang Public School (1896) and Université d’Aurora (1903). The university was officially founded in 1952 after the mergence of chemical or chemistry departments from Jiaotong University, Université d’Aurora, Utopia University, Soochow University and Jiangnan University, and became the first chemical industry oriented university in China named as East China Institute of Chemical Technology. With the value of “Diligence, Factuality, Aspiration and Virtue”, ECUST has always been making every endeavor to develop its united and pioneering spirit since its establishment, and is dedicated to providing its students with advanced knowledge and skills in an academic environment full of intellectual stimulation and scientific innovation. Today, a wide range of programs is offered to cater to the demands of the society and to prepare -

University of California

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Performing Perversion: Decadence in Twentieth-Century Chinese Literature Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/89r2b0jj Author Wang, Hongjian Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Performing Perversion: Decadence in Twentieth-Century Chinese Literature A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Hongjian Wang September 2012 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Perry Link, Chairperson Dr. Paul Pickowicz Dr. Susan Zieger Copyright by Hongjian Wang 2012 The Dissertation of Hongjian Wang is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements This dissertation is the result of an academic adventure that is deeply indebted to the guidance of all my three committee members. Dr. Susan Zieger ushered me into the world of Western Decadence in the late nineteenth century. Dr. Paul Pickowicz instilled into me a strong interest in and the methodology of cultural history studies. Dr. Perry Link guided me through the palace of twentieth-century Chinese literature and encouraged me to study Decadence in modern Chinese literature in comparison with Western Decadence combining the methodology of literary studies and cultural history studies. All of them have been extremely generous in offering me their valuable advices from their expertise, which made this adventure eye-opening and spiritually satisfying. My special gratitude goes to Dr. Link. His broad knowledge and profound understanding of Chinese literature and society, his faith in and love of seeking the truth, and his concern about the fate of ordinary people are inexhaustible sources of inspiration to me.