The Chinese Nationalists' Attempt to Regulate Shanghai, 1927-49 Author(S): Frederic Wakeman, Jr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Quint : an Interdisciplinary Quarterly from the North 1

the quint : an interdisciplinary quarterly from the north 1 Editorial Advisory Board the quint volume ten issue two Moshen Ashtiany, Columbia University Ying Kong, University College of the North Brenda Austin-Smith, University of Martin Kuester, University of Marburg an interdisciplinary quarterly from Manitoba Ronald Marken, Professor Emeritus, Keith Batterbe. University of Turku University of Saskatchewan the north Donald Beecher, Carleton University Camille McCutcheon, University of South Melanie Belmore, University College of the Carolina Upstate ISSN 1920-1028 North Lorraine Meyer, Brandon University editor Gerald Bowler, Independent Scholar Ray Merlock, University of South Carolina Sue Matheson Robert Budde, University Northern British Upstate Columbia Antonia Mills, Professor Emeritus, John Butler, Independent Scholar University of Northern British Columbia David Carpenter, Professor Emeritus, Ikuko Mizunoe, Professor Emeritus, the quint welcomes submissions. See our guidelines University of Saskatchewan Kyoritsu Women’s University or contact us at: Terrence Craig, Mount Allison University Avis Mysyk, Cape Breton University the quint Lynn Echevarria, Yukon College Hisam Nakamura, Tenri University University College of the North Andrew Patrick Nelson, University of P.O. Box 3000 Erwin Erdhardt, III, University of Montana The Pas, Manitoba Cincinnati Canada R9A 1K7 Peter Falconer, University of Bristol Julie Pelletier, University of Winnipeg Vincent Pitturo, Denver University We cannot be held responsible for unsolicited Peter Geller, -

Program Book(EN)

TRANSPORTATION IN CHINA 2025: CONNECTING THE WORLD 中国交通 2025:联通世界 Transportation in China 2025: Connecting the World 1 CONTENTS The 19th COTA International Conference of Transportation Professionals Transportation in China 2025: Connecting the World Welcome Remarks ······································ 4 Organization Council ································· 8 Organizers ······················································ 13 Sponsors ·························································· 17 Instructions for Presenters ························ 19 Instructions for Session Chairs ················ 19 Program at a Glance ··································· 20 Program ··························································· 22 Poster Sessions ············································· 56 General Information ··································· 86 Conference Speakers & Organizers ······· 95 Pre- and Post-CICTP2019 Events ············ 196 • Welcome Remarks It is our great pleasure to welcome you all to the 19th COTA International Conference Welcome of Transportation Professionals (CICTP 2019) in Nanjing, China. The CICTP2019 is jointly Remarks organized by Chinese Overseas Transportation Association (COTA), Southeast University, and Jiaotong International Cooperation Service Center of Ministry of Transport. The CICTP annual conference series was established by COTA back in 2001 and in the past two decades benefited from support from the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), Transportation Research Board (TRB), and many other -

Christian Women and the Making of a Modern Chinese Family: an Exploration of Nü Duo 女鐸, 1912–1951

Christian Women and the Making of a Modern Chinese Family: an Exploration of Nü duo 女鐸, 1912–1951 Zhou Yun A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University February 2019 © Copyright by Zhou Yun 2019 All Rights Reserved Except where otherwise acknowledged, this thesis is my own original work. Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Benjamin Penny for his valuable suggestions and constant patience throughout my five years at The Australian National University (ANU). His invitation to study for a Doctorate at Australian Centre on China in the World (CIW) not only made this project possible but also kindled my academic pursuit of the history of Christianity. Coming from a research background of contemporary Christian movements among diaspora Chinese, I realise that an appreciation of the present cannot be fully achieved without a thorough study of the past. I was very grateful to be given the opportunity to research the Republican era and in particular the development of Christianity among Chinese women. I wish to thank my two co-advisers—Dr. Wei Shuge and Dr. Zhu Yujie—for their time and guidance. Shuge’s advice has been especially helpful in the development of my thesis. Her honest critiques and insightful suggestions demonstrated how to conduct conscientious scholarship. I would also like to extend my thanks to friends and colleagues who helped me with my research in various ways. Special thanks to Dr. Caroline Stevenson for her great proof reading skills and Dr. Paul Farrelly for his time in checking the revised parts of my thesis. -

MMB PP FROMMER's SHANGHAI DAY by DAY NOV 2011-Cover.Jpg

S h a n Hua W G D x a u a i i t o n sheng zhen n Lu s m P u Bund n u L Jade Buddha Hengfeng LuHANZHONG Historicala Huangpu d u o QufLu Bus Station u Y n Temple RD MuseumPark g N N o PUDONG Oriental Pearl a r n Lu BUND n t X me Lu h i ia TV Tower L z X / XINZHA Lujiazui u S a o C RD n The Park u h g g HUANGPU Riverside t an Sh Datian h e B u Bund Ch n zh Lu u e iu EAST Park Century Ave. im E g L N LUJIAZUI g i Holy Trinity a x d L NANJING RD Lujiazui Xi Lu n p on JING’AN en E u u g D r Cathedral hu Lu e ng B iji ng Super Brand s e e Do a Taixing Lu l s B Central Wuging Lu r i PEOPLE’S SQ L w Lu L n Dong Mall u u FuzhouHenan Lu u a a g L u Lu Hospital y an ng Jiujiangn kLuo Renji R y ji a Shanghai ( ng H Yan’ iv Jia e e n Lu Tunne F a Hospital e l r World Financial e g Lu Shanghai s n N don Zhong Lu v g i gning Lu uan d Lu a Shanghai MoCA G Museum of e Center i t Z P X e Shanghai h r H P d Natural History o o Art n u m u WEST ) People’s Urban Planning a m g n e NANJING Museum sh g n in jing Park Exhibition Hall a p a g ei S i Dong Lu min Lu n u d B en L RD h R Gucheng R e Shanghai D u i o iv u m Ningha Park n e i L g r X e Grand Theater Fuyou Lu n Shanghai E ng Shanghai Z r ji h an Y Yuyuan L N Concert Hall Fuyou Rd o u Lu i Museum ai n ih L Garden e u Mosque g Shanghai W u Square L ng DASHIJIE h Exhibition Dagu Lu o H u Park Zh enan a City God Yan’an Zhong Lu g Center lin Shuguang Jin u Jing’an Yan’an Freeway (elevated) Temple Huaihai Hospital L Paramount SOUTH u xing L TempleJING’AN Fu nel R Bird, Fish, Flower & n Ballroom HUANGPI Park -

Sino-Japanese News

Sino-Japanese News * * * * Novermber days, 14 from three For Conference. Sino-Japanese International Fourth the played Tokyo host University in to Kei6 1997, 16, November through Professor Relations. Sino-Japanese History of Symposium the International on organizer, principal committee, • • •d• of the • chairman served Shinkichi program as Korea, Japan, Taiwan, China, from scholars principal fund-raiser. Over 70 all) (above and and chairs, panel participated presenters, and States, France United Canada, the as conference and auditoriums the filled Japan China and from Many discussants. more agreed it that great disagreements, all spite intense of success. In was a some rooms. followed unexpectedly, observer, by this witnessed acrimony not fiercest a The Nanjing especially the opinions differing involved and War" panel "Fifteen-Year the on on the within "discussion" keep this managed sagaciously moderator The to Massacre. blows. it before conclusion panel bring to the civility and general bounds of came to to a follow. titles and affiliations, panels, with conference presenters, of the outline paper An of Japan. Views Panel One. • Naoki Sciences; Hazama Social • Academy of •J" -,• Chinese , Bingmeng Chairs: He [•d]-• •-J, University Kyoto kanry6 Shinch6 nendai okeru ni University, •I•, •'•E "1860-70 Saga Sasaki Y6 •¢ •'•J• •t• • [] • •" • • • 69 baai" 1860-70 Kaku Silt6 Krsh6 Ri Nihonron: to no no and &Japan the 1860s in •, •/• •'•J_•_ • •j• •fi Views (Chinese Officials' 7_1• • 69 Songtao) Hongzhang and Guo ofLi The Cases 1870s: yingxiang: -

Tramway Renaissance

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE www.lrta.org www.tautonline.com OCTOBER 2018 NO. 970 FLORENCE CONTINUES ITS TRAMWAY RENAISSANCE InnoTrans 2018: Looking into light rail’s future Brussels, Suzhou and Aarhus openings Gmunden line linked to Traunseebahn Funding agreed for Vancouver projects LRT automation Bydgoszcz 10> £4.60 How much can and Growth in Poland’s should we aim for? tram-building capital 9 771460 832067 London, 3 October 2018 Join the world’s light and urban rail sectors in recognising excellence and innovation BOOK YOUR PLACE TODAY! HEADLINE SUPPORTER ColTram www.lightrailawards.com CONTENTS 364 The official journal of the Light Rail Transit Association OCTOBER 2018 Vol. 81 No. 970 www.tautonline.com EDITORIAL EDITOR – Simon Johnston [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOr – Tony Streeter [email protected] WORLDWIDE EDITOR – Michael Taplin 374 [email protected] NewS EDITOr – John Symons [email protected] SenIOR CONTRIBUTOR – Neil Pulling WORLDWIDE CONTRIBUTORS Tony Bailey, Richard Felski, Ed Havens, Andrew Moglestue, Paul Nicholson, Herbert Pence, Mike Russell, Nikolai Semyonov, Alain Senut, Vic Simons, Witold Urbanowicz, Bill Vigrass, Francis Wagner, Thomas Wagner, 379 Philip Webb, Rick Wilson PRODUCTION – Lanna Blyth NEWS 364 SYSTEMS FACTFILE: bydgosZCZ 384 Tel: +44 (0)1733 367604 [email protected] New tramlines in Brussels and Suzhou; Neil Pulling explores the recent expansion Gmunden joins the StadtRegioTram; Portland in what is now Poland’s main rolling stock DESIGN – Debbie Nolan and Washington prepare new rolling stock manufacturing centre. ADVertiSING plans; Federal and provincial funding COMMERCIAL ManageR – Geoff Butler Tel: +44 (0)1733 367610 agreed for two new Vancouver LRT projects. -

Virtual Shanghai

ASIA mmm i—^Zilll illi^—3 jsJ Lane ( Tail Sttjaca, New Uork SOif /iGf/vrs FO, LIN CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION Draper CHINA AND THE CHINESE L; THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 House 1918 WINE ATJD~SPIRIT MERCHANTS. PROVISION DEALERS. SHIP CHANDLERS. yigents for jfidn\iratty C/jarts- HOUSE BOATS supplied with every re- quisite for Up-Country Trips. LANE CRAWFORD 8 CO., LTD., NANKING ROAD, SHANGHAI. *>*N - HOME USE RULES e All Books subject to recall All borrowers must regis- ter in the library to borrow books fdr home use. All books must be re- turned at end of college year for inspection and repairs. Limited books must be returned within the four week limit and not renewed. Students must return all books before leaving town. Officers should arrange for ? the return of books wanted during their absence from town. Volumes of periodicals and of pamphlets are held in the library as much as possible. For special pur- poses they are given out for a limited time. Borrowers should not use their library privileges for the benefit of other persons Books of special value nd gift books," when the giver wishes it, are not allowed to circulate. Readers are asked to re- port all cases of books marked or mutilated. Do not deface books by marks and writing. - a 5^^KeservaToiioT^^ooni&^by mail or cable. <3. f?EYMANN, Manager, The Leading Hotel of North China. ^—-m——aaaa»f»ra^MS«»» C UniVerS"y Ubrary DS 796.S5°2D22 Sha ^mmmmilS«u,?,?llJff travellers and — — — — ; KELLY & WALSH, Ltd. -

S40410-021-00136-Z.Pdf

Roche Cárcel City Territ Archit (2021) 8:7 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-021-00136-z RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The spatialization of time and history in the skyscrapers of the twenty-frst century in Shanghai Juan Antonio Roche Cárcel* Abstract This article aims to fnd out to what extent the skyscrapers erected in the late twentieth and early twenty-frst cen- turies, in Shanghai, follow the modern program promoted by the State and the city and how they play an essential role in the construction of the temporary discourse that this modernization entails. In this sense, it describes how the city seeks modernization and in what concrete way it designs a modern temporal discourse. The work fnds out what type of temporal narrative expresses the concentration of these skyscrapers on the two banks of the Huangpu, that of the Bund and that of the Pudong, and fnally, it analyzes the seven most representative and sig- nifcant skyscrapers built in the city in recent years, in order to reveal whether they opt for tradition or modernity, globalization or the local. The work concludes that the past, present and future of Shanghai have been minimized, that its history has been shortened, that it is a liminal site, as its most outstanding skyscrapers, built on the edge of the river and on the border between past and future. For this reason, the author defends that Shanghai, by defn- ing globalization, by being among the most active cities in the construction of skyscrapers, by building more than New York and by building increasingly technologically advanced tall towers, has the possibility to devise a peculiar Chinese modernity, or even deconstruct or give a substantial boost to the general concept of Western modernity. -

Download Here

ISABEL SUN CHAO AND CLAIRE CHAO REMEMBERING SHANGHAI A Memoir of Socialites, Scholars and Scoundrels PRAISE FOR REMEMBERING SHANGHAI “Highly enjoyable . an engaging and entertaining saga.” —Fionnuala McHugh, writer, South China Morning Post “Absolutely gorgeous—so beautifully done.” —Martin Alexander, editor in chief, the Asia Literary Review “Mesmerizing stories . magnificent language.” —Betty Peh-T’i Wei, PhD, author, Old Shanghai “The authors’ writing is masterful.” —Nicholas von Sternberg, cinematographer “Unforgettable . a unique point of view.” —Hugues Martin, writer, shanghailander.net “Absorbing—an amazing family history.” —Nelly Fung, author, Beneath the Banyan Tree “Engaging characters, richly detailed descriptions and exquisite illustrations.” —Debra Lee Baldwin, photojournalist and author “The facts are so dramatic they read like fiction.” —Heather Diamond, author, American Aloha 1968 2016 Isabel Sun Chao and Claire Chao, Hong Kong To those who preceded us . and those who will follow — Claire Chao (daughter) — Isabel Sun Chao (mother) ISABEL SUN CHAO AND CLAIRE CHAO REMEMBERING SHANGHAI A Memoir of Socialites, Scholars and Scoundrels A magnificent illustration of Nanjing Road in the 1930s, with Wing On and Sincere department stores at the left and the right of the street. Road Road ld ld SU SU d fie fie d ZH ZH a a O O ss ss U U o 1 Je Je o C C R 2 R R R r Je Je r E E u s s u E E o s s ISABEL’SISABEL’S o fie fie K K d d d d m JESSFIELD JESSFIELDPARK PARK m a a l l a a y d d y o o o o d d e R R e R R R R a a S S d d SHANGHAISHANGHAI -

Portuguese in Shanghai

CONTENTS Introduction by R. Edward Glatfelter 1 Chapter One: The Portuguese Population of Shanghai..........................................................6 Chapter Two: The Portuguese Consulate - General of Shanghai.........................................17 ---The Personnel of the Portuguese Consulate-General at Shanghai.............18 ---Locations of the Portuguese Consulate - General at Shanghai..................23 Chapter Three: The Portuguese Company of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps........................24 ---Founding of the Company.........................................................................24 ---The Personnel of the Company..................................................................31 Activities of the Company.............................................................................32 Chapter Four: The portuguese Cultural Institutions and Public Organizations....................36 ---The Portuguese Press in Shanghai.............................................................37 ---The Church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus...................................................39 ---The Apollo Theatre....................................................................................39 ---Portuguese Public Organizations...............................................................40 Chapter Five: The Social Problems of the Portuguese in Shanghai.....................................45 ---Employment Problems of the Portuguese in Shanghai..............................45 ---The Living Standard of the Portuguese in Shanghai.................................47 -

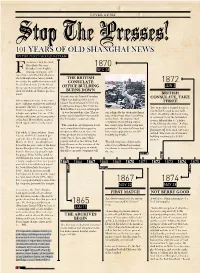

Stop the Presses!

cover story Stop The Presses! 101 YEARS OF OLD SHANGHAI NEWS BY THE THAT’S SHANGHAI TEAM ounded in 1864, the North China Daily News was 1870 Shanghai’s first English- language newspaper and DEC 28 Fone of its most influential. At a time when Shanghai was Asia’s journal- THE BRITISH ism center, the publication was noted CONSULATE 1872 for a balanced voice (for the times), strong reporters and sympathies that OFFICE BUILDING JUN 3 often lay with local Chinese predica- BURNS DOWN ments. BRITISH Shortly after the British Consulate CONSULATE, TAKE It bore witness to some of the city’s Office was built in 1849, it col- THREE most confusing, tumultuous and lurid lapsed. Reconstructed in 1852, the building standing at No. 33 on the moments. The fall of an emperor. Two years after it burned down, a Bund suffered a second catastrophe Violent struggles for power. Triad new British Consulate was built – – it was destroyed in a fire. The re- suit admirably the decimated furni- intrigue and opium. The rise of the which, thankfully, still stands today. porter seems less than impressed by ture and perhaps when everything foreign settlements and crazy parties A ceremony to lay the foundation the Consulate’s temporary digs… settles down, the impoverished at the Astor House Hotel, many of stone is delayed due to “a defect conditions of everything will be which raged until five in the morn- in the Chinese character.” A silver “The consulate and Supreme Court less conspicuous than if going into ing. trowel was ordered from Canton were moved into their respective premises of the extent of these lost, [Guangzhou] to be used, but never temporary offices yesterday, and but present appearances are suf- The whole of these archives – from arrived. -

Treaty-Port English in Nineteenth-Century Shanghai: Speakers, Voices, and Images

Treaty-Port English in Nineteenth-Century Shanghai: Speakers, Voices, and Images Jia Si, Fudan University Abstract This article examines the introduction of English to the treaty port of Shanghai and the speech communities that developed there as a result. English became a sociocultural phenomenon rather than an academic subject when it entered Shanghai in the 1840s, gradually generating various social activities of local Chinese people who lived in the treaty port. Ordinary people picked up a rudimentary knowledge of English along trading streets and through glossary references, and went to private schools to improve their linguistic skills. They used English to communicate with foreigners and as a means to explore a foreign presence dominated by Western material culture. Although those who learned English gained small-scale social mobility in the late nineteenth century, the images of English-speaking Chinese were repeatedly criticized by the literati and official scholars. This paper explores Westerners’ travel accounts, as well as various sources written by the new elite Chinese, including official records and vernacular poems, to demonstrate how English language acquisition brought changes to local people’s daily lives. I argue that treaty-port English in nineteenth-century Shanghai was not only a linguistic medium but, more importantly, a cultural agent of urban transformation. It gradually molded a new linguistic landscape, which at the same time contributed to the shaping of modern Shanghai culture. Introduction The circulation of Western languages through both textual and oral media has enormously affected Chinese society over the past two hundred years. In nineteenth-century China, the English language gradually found a social niche and influenced people’s acceptance of emerging Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review E-Journal No.