S40410-021-00136-Z.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shanghai Tower Construction & Development Co., Ltd

Autodesk Customer Success Story Shanghai Tower Construction & Development Co., Ltd. COMPANY Shanghai Tower Rising to new heights with BIM. Construction & Development Co., Ltd. Shanghai Tower owner champions BIM PROJECT TEAM for design and construction of one of the Gensler Thornton Tomasetti Cosentini Associates world’s tallest (and greenest) buildings. Architectural Design and Research Institute of Tongji University Shanghai Xiandai Engineering Consultants Co., Ltd. Shanghai Construction Group Shanghai Installation Engineering Engineering Co., Ltd. Autodesk Consulting SOFTWARE Autodesk® Revit® Autodesk® Navisworks® Manage Autodesk® Ecotect® Analysis AutoCAD® Autodesk BIM solutions enable the different design disciplines to work together in a seamless fashion on a single information platform—improving efficiency, reducing Image courtesy of Shanghai Tower Construction and Development Co., Ltd. Rendering by Gensler. errors, and improving Project summary featuring a public sky garden, together with cafes, both project and building restaurants, and retail space. The double-skinned A striking new addition to the Shanghai skyline is performance. facade creates a thermal buffer zone to minimize currently rising in the heart of the city’s financial heat gain, and the spiraling nature of the outer district. The super high-rise Shanghai Tower will — Jianping Gu facade maximizes daylighting and views while Director and General Manager soon stand as the world’s second tallest building, reducing wind loads and conserving construction Shanghai Tower Construction and adjacent to two other iconic structures, the materials. To save energy, the facility includes & Development Co., Ltd. Jin Mao Tower and the Shanghai World Financial its own wind farm and geothermal system. In Center. The 121-story transparent glass tower will addition, rainwater recovery and gray water twist and taper as it rises, conveying a unique recycling systems reduce water usage. -

CTBUH Journal

About the Council The Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, based at the Illinois Institute of Technology in CTBUH Journal Chicago and with a China offi ce at Tongji International Journal on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat University in Shanghai, is an international not-for-profi t organization supported by architecture, engineering, planning, development, and construction professionals. Founded in 1969, the Council’s mission is to disseminate multi- Tall buildings: design, construction, and operation | 2014 Issue IV disciplinary information on tall buildings and sustainable urban environments, to maximize the international interaction of professionals involved Case Study: One Central Park, Sydney in creating the built environment, and to make the latest knowledge available to professionals in High-Rise Housing: The Singapore Experience a useful form. The Emergence of Asian Supertalls The CTBUH disseminates its fi ndings, and facilitates business exchange, through: the Achieving Six Stars in Sydney publication of books, monographs, proceedings, and reports; the organization of world congresses, Ethical Implications of international, regional, and specialty conferences The Skyscraper Race and workshops; the maintaining of an extensive website and tall building databases of built, under Tall Buildings in Numbers: construction, and proposed buildings; the Unfi nished Projects distribution of a monthly international tall building e-newsletter; the maintaining of an Talking Tall: Ben van Berkel international resource center; the bestowing of annual awards for design and construction excellence and individual lifetime achievement; the management of special task forces/working groups; the hosting of technical forums; and the publication of the CTBUH Journal, a professional journal containing refereed papers written by researchers, scholars, and practicing professionals. -

Read Book Skyscrapers: a History of the Worlds Most Extraordinary

SKYSCRAPERS: A HISTORY OF THE WORLDS MOST EXTRAORDINARY BUILDINGS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Judith Dupre, Adrian Smith | 176 pages | 05 Nov 2013 | Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers Inc | 9781579129422 | English | New York, United States Skyscrapers: A History of the Worlds Most Extraordinary Buildings PDF Book By crossing the boundaries of strict geometry and modern technologies in architecture, he came up with a masterpiece that has more than a twist in its tail. Item added to your basket. Sophia McCutchen rated it it was amazing Nov 27, The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Standing meters high and weighing half a million tons, Burj Khalifa towers above its city like a giant redwood in a field of daisies. The observation deck on the 43rd floor offers stunning views of Central, one of Hong Kong's busiest districts. It was the tallest of all buildings in the European Union until London's The Shard bumped it to second in The Shard did it, slicing up the skyline and the record books with its meter height overtaking the Commerzbank Headquarters in Frankfurt by nine meters, to become the highest building in the European Union. That it came about due to auto mogul Walter P. Marina Bay Sands , 10 Bayfront Ave. Heather Tribe rated it it was amazing Dec 01, Standing 1, feet tall, the building was one of the first to use new advanced structural engineering that could withstand typhoon winds as well as earthquakes ranging up to a seven on the Richter scale. Construction — mainly using concrete and stone — began around 72AD and finished in 80AD. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: KPF Celebrates Opening of Spring City 66 the Design Reconnects Kunming's Pedestrian Pathways As It Nods

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: KPF Celebrates Opening of Spring City 66 The design reconnects Kunming’s pedestrian pathways as it nods to the unique landscape of Yunnan Province. New York, New York – February 21, 2020 – Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates (KPF) recently celebrated the opening of Spring City 66, a mixed-use development in Kunming, China. One of the largest commercial complexes in the city, the 430,000 m2 Spring City 66 is comprised of a retail podium and office tower that are carefully integrating into the surrounding context. Located adjacent to two major pedestrian-friendly boulevards and metro lines, Spring City 66’s accessibility and public amenities weave this high-density, mixed-use destination directly into the urban fabric of Kunming. Design Inspiration The design for Spring City 66 is responds to Yunnan Province’s unique landscape and its location along historic trade routes. A landscaped promenade, reminiscent of the region’s verdant valleys, is central to the project, while the surrounding undulating retail podium and a crag-like tower nod to the nearby Shilin Stone Forest’s notable limestone formations. The project’s varied program weaves along multiple levels of terraces lined with shops and restaurants, creating a vibrant destination for the city. “The KPF design for Spring City 66 illustrates our belief that the most compelling architecture strongly expresses the spirit of its place. Kunming is a city of outdoor life, of vibrant color, and exciting topography. This building reflects that character in the shape of its roofs, and in its facade materials. We worked closely with Hang Lung, as we have previously in Shanghai, Tianjin, Shenyang, Hangzhou, and Hong Kong, to weave together varied activities of working, shopping, and dwelling into one urban hive of activity,” notes KPF President and Design Principal James von Klemperer. -

Structural Design Challenges of Shanghai Tower

Structural Design Challenges of Shanghai Tower Author: Yi Zhu Affiliation: American Society of Social Engineers Street Address: 398 Han Kou Road, Hang Sheng Building City: Shanghai State/County: Zip/Postal Code: 200001 Country: People’s Republic of China Email Address: [email protected] Fax: 1.917.661.7801 Telephone: 011.86.21.6057.0902 Website: http://www.thorntontomasetti.com Author: Dennis Poon Affiliation: Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat Street Address: 51 Madison Avenue City: New York State/County: NY Zip/Postal Code: 10010 Country: United States of America Email Address: [email protected] Fax: 1.917.661.7801 Telephone: 1.917.661.7800 Website: http://www.thorntontomasetti.com Author: Emmanuel E. Velivasakis Affiliation: American Society of Civil Engineers Street Address: 51 Madison Avenue City: New York State/County: NY Zip/Postal Code: 10010 Country: Unites States of America Email Address: [email protected] Fax: +1.917.661.7801 Telephone: +1.917.661.8072 Website: http://www.thorntontomasetti.com Author: Steve Zuo Affiliation: American Institute of Steel Construction; Structural Engineers Association of New York; American Society of Civil Engineers Street Address: 51 Madison Avenue City: New York State/County: NY Zip/Postal Code: 10010 Country: United States of America Email Address: [email protected] Fax: 1.917.661.7801 Telephone: 1.917.661.7800 Website: http://www.thorntontomasetti.com/ Author: Paul Fu Affiliation: Street Address: 51 Madison Avenue City: New York State/County: NY Zip/Postal Code: 10010 Country: United States of America Email Address: [email protected] Fax: 1.917.661.7801 Telephone: 1.917.661.7800 Website: http://www.thorntontomasetti.com/ Author Bios Yi Zhu, Senior Principal of Thornton Tomasetti, has extensive experience internationally in the structural analysis, design and review of a variety of building types, including high-rise buildings and mixed-use complexes, in both steel and concrete. -

An All-Time Record 97 Buildings of 200 Meters Or Higher Completed In

CTBUH Year in Review: Tall Trends All building data, images and drawings can be found at end of 2014, and Forecasts for 2015 Click on building names to be taken to the Skyscraper Center An All-Time Record 97 Buildings of 200 Meters or Higher Completed in 2014 Report by Daniel Safarik and Antony Wood, CTBUH Research by Marty Carver and Marshall Gerometta, CTBUH 2014 showed further shifts towards Asia, and also surprising developments in building 60 58 14,000 13,549 2014 Completions: 200m+ Buildings by Country functions and structural materials. Note: One tall building 200m+ in height was also completed during 13,000 2014 in these countries: Chile, Kuwait, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, 50 Taiwan, United Kingdom, Vietnam 60 58 2014 Completions: 200m+ Buildings by Countr5,00y 0 14,000 60 13,54958 14,000 13,549 2014 Completions: 200m+ Buildings by Country Executive Summary 40 Note: One tall building 200m+ in height was also completed during ) Note: One tall building 200m+ in height was also completed during 13,000 60 58 13,0014,000 2014 in these countries: Chile, Kuwait, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, (m 13,549 2014 in these Completions: countries: Chile, Kuwait, 200m+ Malaysia, BuildingsSingapore, South byKorea, C ountry 50 Total Number (Total = 97) 4,000 s 50 Taiwan,Taiwan, United United Kingdom, Kingdom, Vietnam Vietnam Note: One tall building 200m+ in height was also completed during ht er 13,000 Sum of He2014 igin theseht scountries: (Tot alChile, = Kuwait, 23,333 Malaysia, m) Singapore, South Korea, 5,000 mb 30 50 5,000 The Council -

The Luxury Malling of Shanghai: Successes and Dissonances in the Chinese City

1 1 Th e Luxury Malling of Shanghai Successes and Dissonances in the Chinese City A g n è s R o c a m o r a Introduction Th is chapter looks at the role of one particular type of urban formation in the redefi nition of Shanghai: the luxury shopping mall. In the 1990s and following China’s post-Cultural Revolution opening to the West as well as the party- state’s adoption of a socialist market economy, the city saw the emergence and rapid proliferation of luxury shopping malls. Multi- storey buildings hosting international brands such as Fendi, Chanel, Louis Vuitton or Coach are recurring sights, with Plaza 66, CITIC and Westgate Mall (known as the Golden Triangle of luxury malls) only a few among the still rising list of luxury shopping malls. Th ese malls are part of a wider phenomenon of urban redevelopment in Shanghai. Indeed throughout the 1990s the city experienced an unprecedented programme of urban renewal, economic restructuring and growth.1 Shanghai shift ed from a manufacturing economy to one focused on fi nance, real estate and the service sector.2 Th is urban and economic shift was refl ected in the restructuring of the spatial organization of the city, with skyscrapers, avenues and newly constructed roads central to its reshaping and globalizing.3 Informed by a series of visits to Shanghai in the course of 2014–16 4 and in dialogue with some of the extant literature on Shanghai and China, the chapter shows that to understand the presence of luxury malls in Shanghai one needs to look at the wider context of China’s embrace of both shopping malls and luxury, as well as at the city’s history as a cosmopolitan consumerist centre (fi rst section). -

China Megastructures: Learning by Experience

AC 2009-131: CHINA MEGASTRUCTURES: LEARNING BY EXPERIENCE Richard Balling, Brigham Young University Page 14.320.1 Page © American Society for Engineering Education, 2009 CHINA MEGA-STRUCTURES: LEARNING BY EXPERIENCE Abstract A study abroad program for senior and graduate civil engineering students is described. The program provides an opportunity for students to learn by experience. The program includes a two-week trip to China to study mega-structures such as skyscrapers, bridges, and complexes (stadiums, airports, etc). The program objectives and the methods for achieving those objectives are described. The relationships between the program objectives and the college educational emphases and the ABET outcomes are also presented. Student comments are included from the first offering of the program in 2008. Introduction This paper summarizes the development of a study abroad program to China where civil engineering students learn by experience. Consider some of the benefits of learning by experience. Experiential learning increases retention, creates passion, and develops perspective. Some things can only be learned by experience. Once, while the author was lecturing his teenage son for a foolish misdeed, his son interrupted him with a surprisingly profound statement, "Dad, leave me alone....sometimes you just got to be young and stupid before you can be old and wise". As parents, it's difficult to patiently let our children learn by experience. The author traveled to China for the first time in 2007. He was blindsided by the rapid pace of change in that country, and by the remarkable new mega-structures. More than half of the world's tallest skyscrapers, longest bridges, and biggest complexes (stadiums, airports, etc) are in China, and most of these have been constructed in the past decade. -

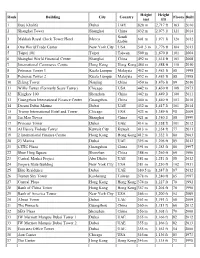

List of World's Tallest Buildings in the World

Height Height Rank Building City Country Floors Built (m) (ft) 1 Burj Khalifa Dubai UAE 828 m 2,717 ft 163 2010 2 Shanghai Tower Shanghai China 632 m 2,073 ft 121 2014 Saudi 3 Makkah Royal Clock Tower Hotel Mecca 601 m 1,971 ft 120 2012 Arabia 4 One World Trade Center New York City USA 541.3 m 1,776 ft 104 2013 5 Taipei 101 Taipei Taiwan 509 m 1,670 ft 101 2004 6 Shanghai World Financial Center Shanghai China 492 m 1,614 ft 101 2008 7 International Commerce Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 484 m 1,588 ft 118 2010 8 Petronas Tower 1 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 8 Petronas Tower 2 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 10 Zifeng Tower Nanjing China 450 m 1,476 ft 89 2010 11 Willis Tower (Formerly Sears Tower) Chicago USA 442 m 1,450 ft 108 1973 12 Kingkey 100 Shenzhen China 442 m 1,449 ft 100 2011 13 Guangzhou International Finance Center Guangzhou China 440 m 1,440 ft 103 2010 14 Dream Dubai Marina Dubai UAE 432 m 1,417 ft 101 2014 15 Trump International Hotel and Tower Chicago USA 423 m 1,389 ft 98 2009 16 Jin Mao Tower Shanghai China 421 m 1,380 ft 88 1999 17 Princess Tower Dubai UAE 414 m 1,358 ft 101 2012 18 Al Hamra Firdous Tower Kuwait City Kuwait 413 m 1,354 ft 77 2011 19 2 International Finance Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 412 m 1,352 ft 88 2003 20 23 Marina Dubai UAE 395 m 1,296 ft 89 2012 21 CITIC Plaza Guangzhou China 391 m 1,283 ft 80 1997 22 Shun Hing Square Shenzhen China 384 m 1,260 ft 69 1996 23 Central Market Project Abu Dhabi UAE 381 m 1,251 ft 88 2012 24 Empire State Building New York City USA 381 m 1,250 -

Download Here

ISABEL SUN CHAO AND CLAIRE CHAO REMEMBERING SHANGHAI A Memoir of Socialites, Scholars and Scoundrels PRAISE FOR REMEMBERING SHANGHAI “Highly enjoyable . an engaging and entertaining saga.” —Fionnuala McHugh, writer, South China Morning Post “Absolutely gorgeous—so beautifully done.” —Martin Alexander, editor in chief, the Asia Literary Review “Mesmerizing stories . magnificent language.” —Betty Peh-T’i Wei, PhD, author, Old Shanghai “The authors’ writing is masterful.” —Nicholas von Sternberg, cinematographer “Unforgettable . a unique point of view.” —Hugues Martin, writer, shanghailander.net “Absorbing—an amazing family history.” —Nelly Fung, author, Beneath the Banyan Tree “Engaging characters, richly detailed descriptions and exquisite illustrations.” —Debra Lee Baldwin, photojournalist and author “The facts are so dramatic they read like fiction.” —Heather Diamond, author, American Aloha 1968 2016 Isabel Sun Chao and Claire Chao, Hong Kong To those who preceded us . and those who will follow — Claire Chao (daughter) — Isabel Sun Chao (mother) ISABEL SUN CHAO AND CLAIRE CHAO REMEMBERING SHANGHAI A Memoir of Socialites, Scholars and Scoundrels A magnificent illustration of Nanjing Road in the 1930s, with Wing On and Sincere department stores at the left and the right of the street. Road Road ld ld SU SU d fie fie d ZH ZH a a O O ss ss U U o 1 Je Je o C C R 2 R R R r Je Je r E E u s s u E E o s s ISABEL’SISABEL’S o fie fie K K d d d d m JESSFIELD JESSFIELDPARK PARK m a a l l a a y d d y o o o o d d e R R e R R R R a a S S d d SHANGHAISHANGHAI -

The-Hows-Whats-And-Wows-Of-Willis

There are enough impressive facts about the When you get back to your school, we hope Willis Tower to make even the most worldly your students will send us photos or write or among us say, “Wow!” So many things at the create artwork about their experiences and Willis Tower can be described by a share them with us (via email or the mailing superlative: biggest, fastest, and longest. But address at the end of this guide). there is more to the building than all these “wows”: 1,450 sky-scraping, cloud-bumping One photo will be selected as the “Photo of feet of glass and steel, 43,000 miles of the Day” and displayed on our Skydeck telephone cable, 25,000 miles of plumbing, monitors for all to see. Artwork and writing 4.56 million square feet of floor space and a will posted on bulletin boards in the view of four states. lunchroom area. We would also love to have you and your students post you Skydeck Behind the “wows” are lots of “hows” and Chicago photos to the Skydeck Chicago pages “whats” for you and your students to on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. explore. In this guide you will be introduced to the building—its beginnings as the Sears As you get ready for your trip, please call us Tower and its design, construction and place with any questions at (312) 875-9447. We aim in the pantheon of skyscrapers. Its name to make your visit your best school trip ever. was recently changed to the Willis Tower, proudly reflecting the name of the global insurance broker who makes the Tower its Chicago home. -

Economics Planning of Super Tall Buildings in Asia Pacific Cities

Economics Planning of Super Tall Buildings in Asia Pacific Cities Dr Paul H K HO, Hong Kong SAR, China Key words: economics planning, super tall building, Asia Pacific SUMMARY The purpose of this paper is to study the economics planning of super tall office buildings in Asia Pacific cities. This study is based on the case study of the Asia Pacific’s 10 tallest buildings which are distributed over six major cities. All are landmark buildings with similar functions. From the analysis of the collected data, the floor plate of these buildings is comparatively large, thus achieving a fairly high lettable to gross floor ratio of about 80% and low wall to floor area ratio of about 0.33. The most common lease span is approximately 12m with column-free between its service core and exterior window. The most common floor-to-floor height is about 4.0m. Square or similar plan is the most common geometry in super tall buildings since this geometry offers the same stiffness in both directions against lateral wind forces. Typically the building is in form of a large podium at lower levels with a setback in the overall floor plan dimension in the main tower and a slightly tapered shape at its top floors. The central core approach in which the core is designed as a structural element to provide stability is commonly used in super tall buildings. By using slip-form or jump-form techniques, a 3 to 4-day cycle is achievable for core wall construction which is similar to steel construction.