Journal of Contemporary History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies

Arabic and its Alternatives Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies Editorial Board Phillip Ackerman-Lieberman (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA) Bernard Heyberger (EHESS, Paris, France) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cjms Arabic and its Alternatives Religious Minorities and Their Languages in the Emerging Nation States of the Middle East (1920–1950) Edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg Karène Sanchez Summerer Tijmen C. Baarda LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Assyrian School of Mosul, 1920s–1930s; courtesy Dr. Robin Beth Shamuel, Iraq. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Murre-van den Berg, H. L. (Hendrika Lena), 1964– illustrator. | Sanchez-Summerer, Karene, editor. | Baarda, Tijmen C., editor. Title: Arabic and its alternatives : religious minorities and their languages in the emerging nation states of the Middle East (1920–1950) / edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg, Karène Sanchez, Tijmen C. Baarda. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Christians and Jews in Muslim societies, 2212–5523 ; vol. -

Appendix A: Soy Adi Kanunu (The Surname Law)

APPENDIX A: SOY ADı KaNUNU (THE SURNaME LaW) Republic of Turkey, Law 2525, 6.21.1934 I. Every Turk must carry his surname in addition to his proper name. II. The personal name comes first and the surname comes second in speaking, writing, and signing. III. It is forbidden to use surnames that are related to military rank and civil officialdom, to tribes and foreign races and ethnicities, as well as surnames which are not suited to general customs or which are disgusting or ridiculous. IV. The husband, who is the leader of the marital union, has the duty and right to choose the surname. In the case of the annulment of marriage or in cases of divorce, even if a child is under his moth- er’s custody, the child shall take the name that his father has cho- sen or will choose. This right and duty is the wife’s if the husband is dead and his wife is not married to somebody else, or if the husband is under protection because of mental illness or weak- ness, and the marriage is still continuing. If the wife has married after the husband’s death, or if the husband has been taken into protection because of the reasons in the previous article, and the marriage has also declined, this right and duty belongs to the closest male blood relation on the father’s side, and the oldest of these, and in their absence, to the guardian. © The Author(s) 2018 183 M. Türköz, Naming and Nation-building in Turkey, https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-56656-0 184 APPENDIX A: SOY ADI KANUNU (THE SURNAME LAW) V. -

LI Lt.R ARY EUROPEAN COMMUNITY INFORMATION SERVICE

COUNCIL OF EUROPE COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL CO-OPERATION AND CULTURAL FUND LI lt.R ARY EUROPEAN COMMUNITY INFORMATION SERVICE. WASHINGTON, D. C. ANNUAL REPORT 1966 STRASBOURG 1967 This report has been prepared by the Council for Cultural Co-operation in pursuance of Article V, paragraph 4, of the Statute of the Cultural Fund, which requires the Council to " transmit an annual report on its activities to the Committee of Ministers, who shall communicate it to the Consultative Assembly ". It has been circulated as a document of the Consultative Assembly of the Council of Europe under the serial number : Doc. 2.235. CONTENTS Page Introduction CHAPTER 1 - Cultural Activities .. .. .. ...... ............ CHAPTER 2 - Higher Education and Research ............. CHAPTER 3 - General and Technical Education .... .. ..... CHAPTER 4 - Out-of-School Education . .... ... ...... .. CHAPTER 5 - Film and Television ....................... CHAPTER 6 - Major Project, Modern Languages ........... CHAPTER 7 - Documentation Centre for Education in Europe .. APPENDICES APPENDIX A - List of participants ....................... APPENDIX B - Structure of the Directorate of Education and of Cultural and Scientific Affairs ..... ..... ...... .. .. APPENDIX C - Reports, publications and material for display .. APPENDIX D - Programme financed by the Cultural Fund in 1966 . .... ....... .... ... ...................... APPENDIX E - Programme to be financed by the Cultural Fund in 1967 .... .. ............. ..... .. .............. .... APPENDIX F - Balance-sheet of the Cultural Fund as at 31 st December 1966 ................. .................. INTRODUCTION The year 1965 had marked the entry of the work of the Council for Cultural Co-operation into a new phase with the definition of a cultural policy of the Council of Europe, the modification of the mandate of one of the Committees, the creation of a new Permanent Committee, and an important expansion in the Directorate of Education and of Cultural and Scientific Affairs. -

Yolunu Kendi Kazan Bir Yolcu: Türk Hukuku Tarihçisi Sadri Maksudi Arsal*

YOLUNU KENDİ KAZAN BİR YOLCU: TÜRK HUKUKU TARİHÇİSİ SADRİ MAKSUDİ ARSAL* Fethi Gedikli** A Passenger Who Did His Own Way: Sadri Maksudi Arsal, a Turkish Legal Historian ÖZ Bu yazıda, Türkiyede “Türk Hukuk Tarihi” disiplininin kurucusu ve ilk tedris edeni Tatar Türklerinin lideri, Kazan doğumlu Sadri Maksudi Arsal’ın hayatının ana nok- talarına, ölümünden sonra hakkında yapılan anma toplantılarına ve hakkında yazılan yerli ve yabancı bazı kitap ve makalelere, İstanbul Hukuk Fakültesindeki faaliyeti, hukukçuluğu ve hukuk tarihçiliği ele alınacaktır. Devlet adamı, siyasetçi, hukukçu, tarihçi, dilci ve milliyet nazariyatçısı bir sosyolog, çok dilli âlimler nesline mensup, dünyanın yıkılışını ve yeniden yapılışını birkaç kaz görmüş bir şahsiyet olarak bugün de yaşamını sürdüren ve her an hakkında konuşulan ve yazılan bir üniversite hocası- nın Türk Tarihi ve Hukuk kitabı ekseninde hukuk tarihçiliği daha yakından mercek altına alınmıştır. * 26.04.2011 günü “Dünden Bugüne İstanbul Üniversitesi Hukuk Fakültesinde Hukuk Tarihi Semineri”nde sunulan tebliğin metnidir. Bu metin, daha önce İstanbul Üniversitesi Hukuk Fakültesi Mecmuası, C. 70, S 1 (2012) s. 399-412 arasında yayınlanan yazımızın gözden geçirilmiş ve bazı küçük ekler yapılmış halidir. a Başlıktaki tanımlama Arsal’dan mülhemdir. “Türk Tarihi ve Hukuk” adlı kitabının önsözünde (s. 3) şöyle demektedir: “Bu şartlar içinde ‘Türk Hukuku Tarihi’ profesörünün vaziyeti, gideceği yolu da kendisi yaparak seyahat eden bir yolcunun durumuna benziyordu”. Daha önce Ahmed Sela- haddin “Tarih-i İlm-i Hukuk” üstüne yazdığı bir yazıda, hocası Mahmud Esad Efendi’yi, benzer şekilde “reh-i nâ-refteye gitmekten tehâşi etmiyor” (“gidilmemiş yola gitmekten çekinmiyor”) diye övmüştü. Bkz. Ahmed Selahaddin, “Kitâbiyât: Âsâr-ı Şarkiyeden: Tarih-i İlm-i Hukuk”, Darulfünûn Hukuk Fakültesi Mecmuası, Sayı. -

Sabiha Gökçen's 80-Year-Old Secret‖: Kemalist Nation

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO ―Sabiha Gökçen‘s 80-Year-Old Secret‖: Kemalist Nation Formation and the Ottoman Armenians A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Fatma Ulgen Committee in charge: Professor Robert Horwitz, Chair Professor Ivan Evans Professor Gary Fields Professor Daniel Hallin Professor Hasan Kayalı Copyright Fatma Ulgen, 2010 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Fatma Ulgen is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii DEDICATION For my mother and father, without whom there would be no life, no love, no light, and for Hrant Dink (15 September 1954 - 19 January 2007 iv EPIGRAPH ―In the summertime, we would go on the roof…Sit there and look at the stars…You could reach the stars there…Over here, you can‘t.‖ Haydanus Peterson, a survivor of the Armenian Genocide, reminiscing about the old country [Moush, Turkey] in Fresno, California 72 years later. Courtesy of the Zoryan Institute Oral History Archive v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………….... -

Turkey's National Struggle: Contrasting Contemporary Views

Turkey’s National Struggle: Contrasting Contemporary Views and Understandings Honors Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors research distinction in History in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by David Richard Howard The Ohio State University June 2011 Project Advisor: Professor Carter Findley, Department of History Howard 2 Introduction: “In the first half of this century an amazing reversal took place—Turkey became a healthy nation in a relatively sick world.”1 This event, after the First World War, was one of the more controversial, mind-changing events of the early twentieth-century. The majority of the world considered the Turkish people to be finished and defeated, but the Turkish National Struggle (1919-1922) proved this opinion quite wrong. This paper examines the factors behind this successful national movement and the birth of the Republic of Turkey by offering comparative insights into contemporary accounts of the National Struggle to close in on the truth. This understanding of the subject will involve analysis and comparison of primary sources (in English) representing several different viewpoints of the period. The Turks were the only defeated people of the First World War to force a rewriting of the peace terms imposed on them at Versailles. The Treaty of Sèvres (1920) left the Turks with but a small part of central Anatolia and the Black Sea coast, and yet they managed to achieve victory in their National Struggle of 1919-1922 and force the Allied powers to a renegotiation of peace terms in the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), thereby recognizing the emergence and legitimacy of the Turkish Republic. -

1 Creating Turkishness: an Examination of Turkish Nationalism Through Gök-Börü Güldeniz Kibris Sabanci University Spring 20

CREATING TURKISHNESS: AN EXAMINATION OF TURKISH NATIONALISM THROUGH GÖK-BÖRÜ GÜLDEN İZ KIBRIS SABANCI UNIVERSITY SPRING 2005 1 CREATING TURKISHNESS: AN EXAMINATION OF TURKISH NATIONALISM THROUGH GÖK-BÖRÜ By GÜLDEN İZ KIBRIS Submitted to the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sabanci University Spring 2005 2 CREATING TURKISHNESS: AN EXAMINATION OF TURKISH NATIONALISM THROUGH GÖK-BÖRÜ APPROVED BY: Assoc. Prof. Halil Berktay (Thesis Supervisor) ........................................................ Asst. Prof. Y. Hakan Erdem ....................................................... Asst. Prof. E. Burak Arıkan ......................................................... DATE OF APPROVAL: 12 August 2005 3 © GÜLDEN İZ KIBRIS 2005 All Rights Reserved 4 Abstract CREATING TURKISHNESS: AN EXAMINATION OF TURKISH NATIONALISM THROUGH GÖK-BÖRÜ Güldeniz Kıbrıs History, M.A. Thesis Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Halil Berktay 2005, ix + 113 pages This M.A. thesis attempts to exhibit the cross-fertilization between the Pan- Turkist and Kemalist varieties of Turkish nationalism through their definitions of ‘Turkishness.’ In the same vein with contemporary nationalisms, the late Ottoman/Republican nationalist elite created ‘Turkishness’ by referring to a mythical past. In that creation process, the Pan-Turkist and Kemalist nationalist discourses historically developed in the same pool and used similar intellectual sources. Though their ultimate goals were different, the two varieties scrutinized very similar racist and nationalist references in their imaginations of Turkish identity as racially superior. In the name of revealing the similarities and differences, a Pan-Turkist journal, Gök-Börü [Grey Wolf] has been examined. Published and edited by Reha Oğuz Türkkan, the journal appeared between 1942 and 1943 as a byproduct of the special aggressive international environment. -

Racist Aspects of Modern Turkish Nationalism

Racist Aspects of Modern Turkish Nationalism Ilia Xypolia University of Aberdeen, UK Abstract: This paper aims to challenge simplifications on race and racism in contemporary Turkish society. In doing so, it draws a macro-historical context wherein the racist component of the Turkish national identity had been shaped. The paper traces the emergence of the core racist elements in the beginning at the 20th century within the ideology propagated by the organisation of the Turkish Hearths (Türk Ocakları). The Turkish History Thesis with its emphasis on ‘race’ attempted to promote not only an affiliation but also a common ancestry between Turkish and Western Civilisation. These arguments were backed by commissioning research carried out in the fields of Anthropology, Archaeology and Linguistics. The main argument of this paper is that the racist components of the national identity in Turkey have been the product of a Eurocentric understanding of world history by consecutive nationalist leaders. Keywords: Racism, Eurocentrism, Nationalism, Whiteness, Turkey. An important but significantly under-researched theme of Turkish national identity over the course of the last 100 years has been its racist elements. Indeed, historians and other social scientists have paid little attention to the racist and racial elements in the shaping of the Turkish national identity. The scholars that have examined related issues seem to have solely focused on Turkish state’s treatment of its own ethnic minorities, notably the Kurds, the Armenians, the Jewish population of 1 Turkey and the Greeks. Many official accounts and historical narratives of Turkish nationalism and its practices omit to fully grasp the development of the ideas based on Turkishness as a ‘pure race’. -

The Politics of Gender and the Making of Kemalist Feminist Activism in Contemporary Turkey (1946–2011)

THE POLITICS OF GENDER AND THE MAKING OF KEMALIST FEMINIST ACTIVISM IN CONTEMPORARY TURKEY (1946–2011) By Selin Çağatay Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Prof. Susan Zimmermann CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2017 Copyright Notice This dissertation contains no materials accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions. The dissertation contains no materials previously written and/or published by another person, except where appropriate acknowledgment is made in the form of bibliographical reference. CEU eTD Collection i Abstract The aim of this dissertation is to contribute to the understanding of the relationship between women's activism and the politics of gender by investigating Kemalist feminism in Turkey as a case study. The dissertation offers a political history of Kemalist feminism that enables an insight into the intertwined relationship between women's activism and the politics of gender. It focuses on the class, national/ethnic, and cultural/religious dynamics of and their implications for Kemalist feminist politics. In so doing, it situates Kemalist feminist activism within the politics of gender in Turkey; that is, it analyzes the relationship between Kemalist feminist activism and other actors in gender politics, such as the state, transnational governance, political parties, civil society organizations, and feminist, Islamist, and Kurdish women's activisms. The analysis of Kemalist feminist activism provided in this dissertation draws on a methodological-conceptual framework that can be summarized as follows. Activism provides the ground for women to become actors of the politics of gender. -

![Imagining Turan: Homeland and Its Political Implications in the Literary Work of Hüseyinzade Ali [Turan] and Mehmet Ziya [Gökalp]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7749/imagining-turan-homeland-and-its-political-implications-in-the-literary-work-of-h%C3%BCseyinzade-ali-turan-and-mehmet-ziya-g%C3%B6kalp-1917749.webp)

Imagining Turan: Homeland and Its Political Implications in the Literary Work of Hüseyinzade Ali [Turan] and Mehmet Ziya [Gökalp]

Middle Eastern Studies ISSN: 0026-3206 (Print) 1743-7881 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fmes20 Imagining Turan: homeland and its political implications in the literary work of Hüseyinzade Ali [Turan] and Mehmet Ziya [Gökalp] Ioannis N. Grigoriadis & Arzu Opçin-Kıdal To cite this article: Ioannis N. Grigoriadis & Arzu Opçin-Kıdal (2020) Imagining Turan: homeland and its political implications in the literary work of Hüseyinzade Ali [Turan] and Mehmet Ziya [Gökalp], Middle Eastern Studies, 56:3, 482-495, DOI: 10.1080/00263206.2019.1706167 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2019.1706167 Published online: 31 Jan 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 109 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fmes20 MIDDLE EASTERN STUDIES 2020, VOL. 56, NO. 3, 482–495 https://doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2019.1706167 Imagining Turan: homeland and its political implications in the literary work of Huseyinzade€ Ali [Turan] and Mehmet Ziya [Gokalp]€ Ioannis N. Grigoriadis and Arzu Opc¸in-Kıdal Department of Political Science & Public Administration, Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey While scholarly interest in the influence of Tatar intellectuals on Turkish nationalism has been strong, less attention has been paid to the interactions between Russian Azerbaijani and Ottoman Turkish intellectuals. While the work of Ismail Gasprinski1 and Yusuf Akc¸ura,2 leading figures in the nationalist mobilization of Turkic populations of the Russian Empire, has attracted substantial consideration,3 the work of Huseyinzade€ Ali [Turan],4 has remained relatively neglected. -

National and Transnational Dynamics of Women's Activism in Turkey In

2016 National and Transnational Dynamics of Women’s Activism in Turkey in the 1950s and 1960s: The Story of the ICW Branch in Ankara Umut Azak and Henk de Smaele This article attempts to analyze the transnational dimension of a forgot- ten period of women’s activism in the 1950s. In the historiography of the Turkish women’s movement, these years have been depicted as an HUDRIVWDWHIHPLQLVPZKLFKUHSODFHGWKHÀUVWZDYHIHPLQLVWPRYHPHQW represented by the Union of Turkish Women in the mid-1930s and would later be challenged by the second-wave feminism that emerged as a radical and independent movement in the 1980s. It was during the 1950s, however, that a transnational women’s network was revived since the convening of the Twelfth Congress of the International Alli- ance of Women in Istanbul in 1935. This article unearths the story of the establishment of the Turkish branch of the International Council of Women in the late 1950s and contextualizes this transnational encounter of activist women in a local and international setting, which was both heavily imbued with nationalist and Eurocentric concepts. eminist scholars have recently argued that the international spread of FWestern-style feminism has been complicit in establishing and perpetu- ating Western global dominance, and there is now a rich body of literature on feminist Orientalism, racism, and imperialism. 1 In their critical analyses of the working of power in modern societies, radical historians have simi- larly demonstrated how European “progressive” movements were implied in (neo)colonial and (neo)imperialist projects. 2 This article builds on that scholarship, focusing on a much neglected topic and period in women’s history: the transnational and national dynamics of women’s activism in Turkey in the 1950s. -

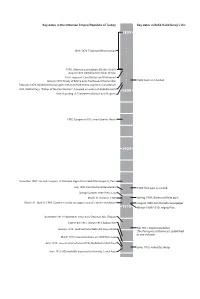

Key Dates in Refik Halid Karay's Life

Philliou - Timeline 5th proof Bill Nelson 6/9/20 Key dates in the Ottoman Empire/Republic of Turkey Key dates in Rek Halid Karay’s life: Key dates in the Ottoman Empire/Republic of Turkey Key dates in Rek Halid Karay’s life: 1914: Marries Nâzime in Sinop while in exile 1839 August 1914: Ottoman Empire enters period of “Active Neutrality” 1915 November 1914: Ottoman Empire enters World War One in earnest July 1915: transferred to Çorum Spring 1915–1916: Armenian Genocide August 1916: transferred to Ankara 1839–1876: Tanzimat Reform period October 1916: transferred to Bilecik October 30,1918: Ottoman defeat in World War One; Armistice of Mudros January 1918: returns to Istanbul 1876: Ottoman constitution (Kânûn-i Esâsî) January 1919: Paris Peace Conference convenes August 1876: Abdülhamid II takes throne May 1919: Greek invasion of Izmir Fall 1918: rst novel: The True Face of Istanbul 1878: suspends Constitution and Parliament (İstanbul’un İç Yüzü) January 1878: Treaty of Edirne ends the Russo-Ottoman War 1888: born in Istanbul June–September 1919: mobilization of resistance forces under leadership of Mustafa Kemal [Atatürk] April–October 1919: Post Telegraph and Telephone February 1878: Abülhamid II prorogues Ottoman Parliament, suspends Constitution 1920: Last Ottoman Parliament passes National Pact [Misak-ı Millî] General Directorate, rst tenure 1884: Midhat Paşa, “Father of the Constitution” strangled on orders of Abdülhamid II 1920 1900 March 16, 1920: British occupation of Istanbul becomes ocial March–April 1920: PTT General Directorate,