Beowulf As Epic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Widsith, Beowulf, Finnsburgh, Waldere, Deor. Done Into Common

Dear Reader, This book was referenced in one of the 185 issues of 'The Builder' Magazine which was published between January 1915 and May 1930. To celebrate the centennial of this publication, the Pictoumasons website presents a complete set of indexed issues of the magazine. As far as the editor was able to, books which were suggested to the reader have been searched for on the internet and included in 'The Builder' library.' This is a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by one of several organizations as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. Wherever possible, the source and original scanner identification has been retained. Only blank pages have been removed and this header- page added. The original book has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books belong to the public and 'pictoumasons' makes no claim of ownership to any of the books in this library; we are merely their custodians. Often, marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in these files – a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Since you are reading this book now, you can probably also keep a copy of it on your computer, so we ask you to Keep it legal. -

Postcolonial Anglo-Saxon in John Haynes's Letter to Patience

‘No word for it’: Postcolonial Anglo-Saxon in John Haynes’s Letter to Patience CHRISTOPHER JONES University of St Andrews This article examines a number of allusions to Old English, especially to the poem The Wanderer, in John Haynes’s award- winning poem Letter to Patience (2006). A broad historical contextualisation of the use of Anglo-Saxon in modern poetry is offered first, against which Haynes’s specific poetic Anglo- Saxonism is then analysed in detail. Consideration is given to the sources – editions and translations – that Haynes used, and a sustained close reading of sections of his poem is offered in the light of this source study. The representation of English as an instrument of imperialism is discussed and juxtaposed with the use and status of early English to offer a long historical view of the politics of the vernacular. It is argued that Haynes’s poem, set partly in Nigeria, represents a new departure in the use it finds for Old English poetry, in effect constituting a kind of ‘postcolonial Anglo-Saxonism’. ohn Haynes’s book-length poem of 2006, his Letter to Patience, is J noteworthy for its use of Anglo-Saxon (also known as Old English) and its allusions to literary works in that language.1 In part, therefore, Letter to Patience constitutes an example of Anglo-Saxonism, a phenomenon which can be defined as the post-Anglo-Saxon appropriation and deployment of Anglo-Saxon language, literature, or culture, an appropriation which is often difficult to separate from the simultaneous reception and construction of ideas about actual Anglo- 1 John Haynes, Letter to Patience (Bridgend, 2006). -

Richard Wilbur's 'Junk'

15 Recycling Anglo-Saxon Poetry: Richard Wilbur’s ‘Junk’ and a Self Study Chris Jones University of St Andrews Ever since scraps, both literal and metaphorical, of Anglo-Saxon (also called Old English) verse began to be recovered and edited in more systematic fashion, modern poets have tried to imagine and recreate its sounds in their own work.1 Often the manuscript materials in which Anglo-Saxon poetry survives show signs of having been uncared for and even mistreated; the tenth-century Exeter Book of poetry, for example, which preserves many of the texts now taught in universities as canonical, is scarred with the stains of having had some kind of vessel laid on it, as if it were a drinks mat, with knife-scores, as if it were a chopping board, and with singe marks, as if some red-hot object was temporarily rested on its back (Muir 2000: II, 2). Such treatment is scarce wonder, given that changes in both language and handwriting must have made such manuscripts unintelligible to all but a few until the studies of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century antiquarians began to render them legible again. But it is salutary to remember that fragments of the past which we hold valuable now have often been the junk of intervening ages, waste materials for which only some alternative function might save them from disposal. Recycled, however, fresh uses may be found for Anglo-Saxon poetry, uses that generate for it new currency, in addition to whatever independent value its stock possesses. This essay sets out to examine some of the generative possibilities of recycling Anglo-Saxon poetry, both from a critic’s perspective and a practitioner’s. -

Compound Diction and Traditional Style in Beowulf and Genesis A

Oral Tradition, 6/1 (1991): 79-92 Compound Diction and Traditional Style in Beowulf and Genesis A Jeffrey Alan Mazo One of the most striking features of Anglo-Saxon alliterative poetry is the extraordinary richness of the vocabulary. Many words appear only in poetry; almost every poem contains words, usually nominal or adjectival compounds, which occur nowhere else in the extant literature. Creativity in coining new compounds reaches its apex in the 3182-line heroic epic Beowulf. In his infl uential work The Art of Beowulf, Arthur G. Brodeur sets out the most widely accepted view of the diction of that poem (1959:28): First, the proportion of such compounds in Beowulf is very much higher than that in any other extant poem; and, secondly, the number and the richness of the compounds found in Beowulf and nowhere else is astonishingly large. It seems reasonable, therefore, to regard the many unique compounds in Beowulf, fi nely formed and aptly used, as formed on traditional patterns but not themselves part of a traditional vocabulary. And to say that they are formed on traditional patterns means only that the character of the language spoken by the poet and his hearers, and the traditional tendency towards poetic idealization, determined their character and form. Their elevation, and their harmony with the poet’s thought and feeling, refl ect that tendency, directed and controlled by the genius of a great poet. It goes without saying that the poet of Beowulf was no “unwashed illiterate,” but a highly trained literary artist who could transcend the traditional medium. -

Oral Tradition

_____________________________________________________________ Volume 6 January 1991 Number 1 _____________________________________________________________ Editor Editorial Assistants John Miles Foley Sarah J. Feeny David Henderson Managing Editor Whitney Strait Lee Edgar Tyler J. Chris Womack Book Review Editor Adam Brooke Davis Slavica Publishers, Inc. Slavica Publishers, Inc. For a complete catalog of books from Slavica, with prices and ordering information, write to: Slavica Publishers, Inc. P.O. Box 14388 Columbus, Ohio 43214 ISSN: 0883-5365 Each contribution copyright (c) 1991 by its author. All rights reserved. The editor and the publisher assume no responsibility for statements of fact or opinion by the authors. Oral Tradition seeks to provide a comparative and interdisciplinary focus for studies in oral literature and related fields by publishing research and scholarship on the creation, transmission, and interpretation of all forms of oral traditional expression. As well as essays treating certifiably oral traditions, OT presents investigations of the relationships between oral and written traditions, as well as brief accounts of important fieldwork, a Symposium section (in which scholars may reply at some length to prior essays), review articles, occasional transcriptions and translations of oral texts, a digest of work in progress, and a regular column for notices of conferences and other matters of interest. In addition, occasional issues will include an ongoing annotated bibliography of relevant research and the annual Albert Lord and Milman Parry Lectures on Oral Tradition. OT welcomes contributions on all oral literatures, on all literatures directly influenced by oral traditions, and on non-literary oral traditions. Submissions must follow the list-of reference format (style sheet available on request) and must be accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope for return or for mailing of proofs; all quotations of primary materials must be made in the original language(s) with following English translations. -

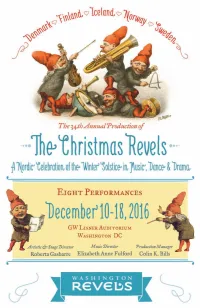

Cr2016-Program.Pdf

l Artistic Director’s Note l Welcome to one of our warmest and most popular Christmas Revels, celebrating traditional material from the five Nordic countries: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. We cannot wait to introduce you to our little secretive tomtenisse; to the rollicking and intri- cate traditional dances, the exquisitely mesmerizing hardingfele, nyckelharpa, and kantele; to Ilmatar, heaven’s daughter; to wild Louhi, staunch old Väinämöinen, and dashing Ilmarinen. This “journey to the Northlands” beautifully expresses the beating heart of a folk community gathering to share its music, story, dance, and tradition in the deep midwinter darkness. It is interesting that a Christmas Revels can feel both familiar and entirely fresh. Washing- ton Revels has created the Nordic-themed show twice before. The 1996 version was the first show I had the pleasure to direct. It was truly a “folk” show, featuring a community of people from the Northlands meeting together in an annual celebration. In 2005, using much of the same script and material, we married the epic elements of the story with the beauty and mystery of the natural world. The stealing of the sun and moon by witch queen Louhi became a rich metaphor for the waning of the year and our hope for the return of warmth and light. To create this newest telling of our Nordic story, especially in this season when we deeply need the circle of community to bolster us in the darkness, we come back to the town square at a crossroads where families meet at the holiday to sing the old songs, tell the old stories, and step the circling dances to the intricate stringed fiddles. -

The Significant Other: a Literary History of Elves

1616796596 The Significant Other: a Literary History of Elves By Jenni Bergman Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cardiff School of English, Communication and Philosophy Cardiff University 2011 UMI Number: U516593 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U516593 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted on candidature for any degree. Signed .(candidate) Date. STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. (candidate) Date. STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. Signed. (candidate) Date. 3/A W/ STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed (candidate) Date. STATEMENT 4 - BAR ON ACCESS APPROVED I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan after expiry of a bar on accessapproved bv the Graduate Development Committee. -

Old English Literature: a Brief Summary

Volume II, Issue II, June 2014 - ISSN 2321-7065 Old English Literature: A Brief Summary Nasib Kumari Student J.k. Memorial College of Education Barsana Mor Birhi Kalan Charkhi Dadri Introduction Old English literature (sometimes referred to as Anglo-Saxon literature) encompasses literature written in Old English (also called Anglo-Saxon) in Anglo-Saxon England from the 7th century to the decades after the Norman Conquest of 1066. "Cædmon's Hymn", composed in the 7th century according to Bede, is often considered the oldest extant poem in English, whereas the later poem, The Grave is one of the final poems written in Old English, and presents a transitional text between Old and Middle English.[1] Likewise, the Peterborough Chronicle continues until the 12th century. The poem Beowulf, which often begins the traditional canon of English literature, is the most famous work of Old English literature. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle has also proven significant for historical study, preserving a chronology of early English history.Alexander Souter names the commentary on Paul's epistles by Pelagius "the earliest extant work by a British author".[2][3] In descending order of quantity, Old English literature consists of: sermons and saints' lives, biblical translations; translated Latin works of the early Church Fathers; Anglo-Saxon chronicles and narrative history works; laws, wills and other legal works; practical works ongrammar, medicine, geography; and poetry.[4] In all there are over 400 survivingmanuscripts from the period, of which about 189 are considered "major".[5] Besides Old English literature, Anglo-Saxons wrote a number of Anglo-Latin works. -

Textual Community and Linguistic Distance in Early England

Textual Community and Linguistic Distance in Early England by Emily Elisabeth Butler A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Emily Elisabeth Butler 2010 Textual Community and Linguistic Distance in Early England Emily Elisabeth Butler Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto 2010 Abstract This dissertation examines the function of textual communities in England from the early Middle Ages until the early modern period, exploring the ways in which cultures and communities are formed through textual activities other than writing itself. I open by discussing the characteristics of a textual community in order to establish a new understanding of the term. I argue that a textual community is fundamentally based on activity carried out in books and that perceptions of linguistic distance stimulate this activity. Chapter 1 investigates Bede (c. 673–735) and his interest in multilingualism, coupled with his exploration of the boundaries between the written and spoken forms of English. Picking up on an element of Bede‘s work, I argue in Chapter 2 that Alfred (r. 871–899) and his grandson Æthelstan (r. 924/5–939) found new ways to make textuality the defining quality of the emerging West Saxon kingdom. In Chapter 3, I focus on the intralingual distance in the textual community surrounding the works of Ælfric (c. 950–1010) and Wulfstan (d. 1023). I also discuss the role of contemporary or near- contemporary manuscript use in forming a textual community at the intersection of ecclesiastical and political power. -

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress)

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress) AC 1 E8 1976 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1976. AC 1 E8 1978 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1978. AC 1 E8 D3 Dasent, George Webbe, trans. The Story of Burnt Njal. London: Dent, 1949. AC 1 E8 G6 Gordon, R.K., trans. Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: Dent, 1936. AC 1 G72 St. Augustine. Confessions. Trans. R.S. Pine-Coffin. New York: Penguin,1978. AC 5 V3 v.2 Essays in Honor of Walter Clyde Curry. Vol. 2. Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, 1954. AC 8 B79 Bryce, James. University and Historical Addresses. London: Macmillan, 1913. AC 15 C55 Brannan, P.T., ed. Classica Et Iberica: A Festschrift in Honor of The Reverend Joseph M.-F. Marique. Worcester, MA: Institute for Early Christian Iberian Studies, 1975. AE 2 B3 Anglicus, Bartholomew. Medieval Lore: An Epitome of the Science, Geography, Animal and Plant Folk-lore and Myth of the Middle Age. Ed. Robert Steele. London: Elliot Stock, 1893. AE 2 H83 Hugh of St. Victor. The Didascalion. Trans. Jerome Taylor. New York: Columbia UP, 1991. 2 copies. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri I-X. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri XI-XX. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AS 122 L5 v.32 Edwards, J. Goronwy. -

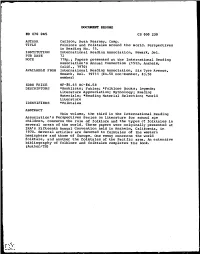

Institution Available from Descriptors

DOCUMENT RES UME ED 070 045 CS 000 230 AUTHOR Carlson, Ruth Kearney, Comp. TITLE Folklore and Folktales Around the world. Perspectives in Reading No. 15. INSTITUTION International Reading Association, Newark, Del., PUB DATE 72 NOTE 179p.; Papers presented at the International Reading Association'sAnnual Convention (15th, Anaheim, Calif., 1970) AVAILABLE FROMInternationalReading Association, Six Tyre Avenue, Newark, Del.19711 ($4.50 non-member, $3.50 member) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *Booklists; Fables; *Folklore Books; Legends; Literature Appreciation; Mythology; Reading Materials; *Reading Material Selection; *world Literature IDENTIFIERS *Folktales ABSTRACT This volume, the third in the International Reading Association's Perspectives Series on literature for school age children, concerns the role of folklore and the types of folktales in several areas of the world. These papers were originally presented at IRA's Fifteenth Annual Convention held in Anaheim, California, in 1970. Several articles are devoted to folktales of the western hemisphere and those of Europe. One essay concerns the world folktale, and another the folktales of the Pacific area. An extensive bibliography of folklore and folktales completes the book. (Author/TO) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO. DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG. INATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN IONS ST ATFD DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU CATION POSITION OR POLICY Perspectives in Reading No. 15 FOLKLORE AND FOLKTALES AROUND THE WORLD Compiled and Edited by Ruth Kearney Carlson California State College at Hayward Prepared by theIRALibrary and Literature Committee Ira INTERNATIONAL READING ASSOCIATION Newark, Delaware 19711 9 b INTERNATIONAL READING ASSOCIATION OFFICERS 1971-1972 President THEODORE L. -

Writers of Tales: a Study on National Literary Epic Poetry with a Comparative Analysis of the Albanian and South Slavic Cases

DOI: 10.14754/CEU.2017.02 WRITERS OF TALES: A STUDY ON NATIONAL LITERARY EPIC POETRY WITH A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE ALBANIAN AND SOUTH SLAVIC CASES FRANCESCO LA ROCCA A DISSERTATION IN HISTORY Presented to the Faculties of the Central European University in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Budapest, Hungary 2016 Supervisor of Dissertation CEU eTD Collection György Endre Szőnyi DOI: 10.14754/CEU.2017.02 COPYRIGHT NOTICE AND STATEMENT OF RESPONSIBILITY Copyright in the text of this dissertation rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European University Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. I hereby declare that this dissertation contains no materials accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions and no materials previously written and/or published by another person unless otherwise noted. CEU eTD Collection DOI: 10.14754/CEU.2017.02 iii ABSTRACT In this dissertation I intend to investigate the history and theory of national literary epic poetry in Europe, paying particular attention to its development among Albanians, Croats, Montenegrins, and Serbs. The first chapters will be devoted to the elaboration of a proper theoretical background and historical framing to the concept of national epic poetry and its role in the cultivation of national thought in Europe.