The Significant Other: a Literary History of Elves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Time, Infinity, Recursion, and Liminality in the Writings of Jorge Luis Borges

Kevin Wilson Of Stones and Tigers; Time, Infinity, Recursion, and Liminality in the writings of Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) and Pu Songling (1640-1715) (draft) The need to meet stones with tigers speaks to a subtlety, and to an experience, unique to literary and conceptual analysis. Perhaps the meeting appears as much natural, even familiar, as it does curious or unexpected, and the same might be said of meeting Pu Songling (1640-1715) with Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986), a dialogue that reveals itself as much in these authors’ shared artistic and ideational concerns as in historical incident, most notably Borges’ interest in and attested admiration for Pu’s work. To speak of stones and tigers in these authors’ works is to trace interwoven contrapuntal (i.e., fugal) themes central to their composition, in particular the mutually constitutive themes of time, infinity, dreaming, recursion, literature, and liminality. To engage with these themes, let alone analyze them, presupposes, incredibly, a certain arcane facility in navigating the conceptual folds of infinity, in conceiving a space that appears, impossibly, at once both inconceivable and also quintessentially conceptual. Given, then, the difficulties at hand, let the following notes, this solitary episode in tracing the endlessly perplexing contrapuntal forms that life and life-like substances embody, double as a practical exercise in developing and strengthening dynamic “methodologies of the infinite.” The combination, broadly conceived, of stones and tigers figures prominently in -

The Argonautica, Book 1;

'^THE ARGONAUTICA OF GAIUS VALERIUS FLACCUS (SETINUS BALBUS BOOK I TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY H. G. BLOMFIELD, M.A., I.C.S. LATE SCHOLAR OF EXETER COLLEGE, OXFORD OXFORD B. H. BLACKWELL, BROAD STREET 1916 NEW YORK LONGMANS GREEN & CO. FOURTH AVENUE AND 30TH STREET TO MY WIFE h2 ; ; ; — CANDIDO LECTORI Reader, I'll spin you, if you please, A tough yarn of the good ship Argo, And how she carried o'er the seas Her somewhat miscellaneous cargo; And how one Jason did with ease (Spite of the Colchian King's embargo) Contrive to bone the fleecy prize That by the dragon fierce was guarded, Closing its soporific eyes By spells with honey interlarded How, spite of favouring winds and skies, His homeward voyage was retarded And how the Princess, by whose aid Her father's purpose had been thwarted, With the Greek stranger in the glade Of Ares secretly consorted, And how his converse with the maid Is generally thus reported : ' Medea, the premature decease Of my respected parent causes A vacancy in Northern Greece, And no one's claim 's as good as yours is To fill the blank : come, take the lease. Conditioned by the following clauses : You'll have to do a midnight bunk With me aboard the S.S. Argo But there 's no earthly need to funk, Or think the crew cannot so far go : They're not invariably drunk, And you can act as supercargo. — CANDIDO LECTORI • Nor should you very greatly care If sometimes you're a little sea-sick; There's no escape from mal-de-mer, Why, storms have actually made me sick : Take a Pope-Roach, and don't despair ; The best thing simply is to be sick.' H. -

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

The Last Train Changeling

SW00121 & SW00122 CHANGELING by angela forrest THE LAST TRAIN by val ormrod CHANGELING by Angela Forrest September, 2015 He isnae mine, hasnae been for twelve years. I know that now. It took a good long while tae admit it and I’ve tried tae make up for lost time, for a’ the years I dithered about whether or not it wis true. These last few years especially I’ve done ma best, done right by Lorna and wee Olivia even if they couldnae understand. They don’t know whit he is. They don’t know Bradley left us a long time ago, that day in the woods. September, 2003 This is ma favourite place. The way the trees come crowing up tae the shore of the loch, closing us in tae our own wee private beach: ye cannae beat it. Lorna’s minding the baby, letting her roll around on the picnic blanket among the half-chewed cheese and ham pieces. She’s still a stunner, my Lorna, even after having two weans. Run ragged looking after them, so she is, but ye’d never know it looking at her. She’s kept her hair long and bonny, not like a lot of they mum’s I see at the school gates. I catch her eye and she gies me a wink and a smile, holding up Olivia’s wee hand to wave at me. I wave back at ma girls and have a check in with ma boy. He’s near enough up tae my waist now. He’s trying tae skip stones across the water but they’re landing wi’ splattering plops. -

The Symbolism of the Dragon

1 THE SYMBOLISM OF THE DRAGON Chinese flying dragon (courtesy of dreamstime.com Ensiferrum 7071168) THE PRIMORDIAL SEVEN, THE FIRST SEVEN BREATHS OF THE DRAGON OF WISDOM, PRODUCE IN THEIR TURN FROM THEIR HOLY CIRCUMGYRATING BREATHS THE FIERY WHIRLWIND. The Stanzas of Dzyan Out of the whirlwind spoke the voice that ignites, that sounds like no voice ever heard. It is, instead, a flame that swirls down out of yawning darkness and scorches the flanks of the trembling world. Amongst the clouds gathered in storm, its fiery curves are sometimes glimpsed and the scraping of its taloned feet echo up the blackened caverns leading to the bowels of the earth. These are aspects of its voice . extensions of its flaming breath. They shine like glittering scales spiralling through the atmosphere. They project forth in the wake of that thunderous tone which issues from the depths of the very source of sound, from the primordial throat which opens out to another world. Thus it is that dragons float at the edge of the universe and near the apertures leading to unknown but frightening realms. Their fiery breath resounds and their reptilian form expands and contracts into myriad shapes described in thousands of stories the world over. But their exact nature remains a mystery and, despite their legendary reputation, for many persons they have never existed. It has been held that the dragon, "while sacred and to be worshipped, has within himself something still more of the divine nature of which it is better to remain in ignorance". Something double-edged is suggested here, and the question of the existence of the dragon deepens to become one of how to approach the Divine without being incinerated by its lower emanations. -

'Goblinlike, Fantastic: Little People and Deep Time at the Fin De Siècle

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output ’Goblinlike, fantastic: little people and deep time at the fin de siècle https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40443/ Version: Full Version Citation: Fergus, Emily (2019) ’Goblinlike, fantastic: little people and deep time at the fin de siècle. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email ‘Goblinlike, Fantastic’: Little People and Deep Time at the Fin De Siècle Emily Fergus Submitted for MPhil Degree 2019 Birkbeck, University of London 2 I, Emily Fergus, confirm that all the work contained within this thesis is entirely my own. ___________________________________________________ 3 Abstract This thesis offers a new reading of how little people were presented in both fiction and non-fiction in the latter half of the nineteenth century. After the ‘discovery’ of African pygmies in the 1860s, little people became a powerful way of imaginatively connecting to an inconceivably distant past, and the place of humans within it. Little people in fin de siècle narratives have been commonly interpreted as atavistic, stunted warnings of biological reversion. I suggest that there are other readings available: by deploying two nineteenth-century anthropological theories – E. B. Tylor’s doctrine of ‘survivals’, and euhemerism, a model proposing that the mythology surrounding fairies was based on the existence of real ‘little people’ – they can also be read as positive symbols of the tenacity of the human spirit, and as offering access to a sacred, spiritual, or magic, world. -

Dragonlore Issue 37 08-11-03

The bird was a Rukh and the white dome, of course, was its egg. Sindbad lashes himself to the bird’s leg with his turban, and the next morning is whisked off into flight and set down on a mountaintop, without having excited the Rukh’s attention. The narrator adds that the Rukh feeds itself on serpents of such great bulk that they would have made but one gulp of an elephant. In Marco Polo’s Travels (III, 36) we read: Dragonlore The people of the island [of Madagascar] report that at a certain season of the year, an extraordinary kind of bird, which they call a rukh, makes its appearance from The Journal of The College of Dracology the southern region. In form it is said to resemble the eagle but it is incomparably greater in size; being so large and strong as to seize an elephant with its talons, and to lift it into the air, from whence it lets it fall to the ground, in order that when dead it Number 37 Michaelmas 2003 may prey upon the carcase. Persons who have seen this bird assert that when the wings are spread they measure sixteen paces in extent, from point to point; and that the feathers are eight paces in length, and thick in proportion. Marco Polo adds that some envoys from China brought the feather of a Rukh back to the Grand Kahn. A Persian illustration in Lane shows the Rukh bearing off three elephants in beak and talons; ‘with the proportion of a hawk and field mice’, Burton notes. -

Horse Motifs in Folk Narrative of the Supernatural

HORSE MOTIFS IN FOLK NARRATIVE OF THE SlPERNA TURAL by Victoria Harkavy A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies Committee: ___ ~C=:l!L~;;rtl....,19~~~'V'l rogram Director Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: ~U_c-ly-=-a2..!-.:t ;LC>=-----...!/~'fF_ Spring Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Horse Motifs in Folk Narrative of the Supernatural A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University by Victoria Harkavy Bachelor of Arts University of Maryland-College Park 2006 Director: Margaret Yocom, Professor Interdisciplinary Studies Spring Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA This work is licensed under a creative commons attribution-noderivs 3.0 unported license. ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to my wonderful and supportive parents, Lorraine Messinger and Kenneth Harkavy. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee, Drs. Yocom, Fraser, and Rashkover, for putting in the time and effort to get this thesis finalized. Thanks also to my friends and colleagues who let me run ideas by them. Special thanks to Margaret Christoph for lending her copy editing expertise. Endless gratitude goes to my family taking care of me when I was focused on writing. Thanks also go to William, Folklore Horse, for all of the inspiration, and to Gumbie, Folklore Cat, for only sometimes sitting on the keyboard. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract .............................................................................................................................. vi Interdisciplinary Elements of this Study ............................................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

Sumdog Spelling Words

Sumdog spelling words a acrobat age amuse applauded assemble babies aardvark acrobatic ageless amusement applause assent baboon abandon across aggression amusements apple assessment baboons abandoned act aggressive an appliance assignment baby abbey action ago anagram applicable assist baby’s abbeys active agony analyse applicably assistance babysitter abbreviation activity agoraphobia analysis application assistant back abducted actor agree ancestor applied assorted backbone Aberdeen actress agreeable anchor applies assume backed abilities actual agreed ancient apply assurance backfired ability actually agreement and applying asterisk backflip able adapt aground android appointment asteroid background abnormal add ahead angel apprentice astonish backhand abnormalities addict ahoy angelic apprenticeship astonishing backing aboard addiction aid anger apprenticeships astrology backpack abominable addition ail angle approach astronaut backside aboriginal additional aim angler appropriate astronomy backstage about address aimless angles approximate at backstretch above addressed air angrier April ate backstroke abracadabra addresses Airdrie angriest aqua athlete backup abrasive adjective airport angrily aquaplane athletic backward abroad adjust aisle animal aquarium atlas backwards abrupt adjustment ajar animals aquatic atmosphere backyard absence admiration alarm ankle aqueduct atom bacon absent admire albatross anniversaries arachnophobia atomic bacteria absolute admission album anniversary arc attach bad absolutely admit alcohol announce -

The Prose Edda

THE PROSE EDDA SNORRI STURLUSON (1179–1241) was born in western Iceland, the son of an upstart Icelandic chieftain. In the early thirteenth century, Snorri rose to become Iceland’s richest and, for a time, its most powerful leader. Twice he was elected law-speaker at the Althing, Iceland’s national assembly, and twice he went abroad to visit Norwegian royalty. An ambitious and sometimes ruthless leader, Snorri was also a man of learning, with deep interests in the myth, poetry and history of the Viking Age. He has long been assumed to be the author of some of medieval Iceland’s greatest works, including the Prose Edda and Heimskringla, the latter a saga history of the kings of Norway. JESSE BYOCK is Professor of Old Norse and Medieval Scandinavian Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Professor at UCLA’s Cotsen Institute of Archaeology. A specialist in North Atlantic and Viking Studies, he directs the Mosfell Archaeological Project in Iceland. Prof. Byock received his Ph.D. from Harvard University after studying in Iceland, Sweden and France. His books and translations include Viking Age Iceland, Medieval Iceland: Society, Sagas, and Power, Feud in the Icelandic Saga, The Saga of King Hrolf Kraki and The Saga of the Volsungs: The Norse Epic of Sigurd the Dragon Slayer. SNORRI STURLUSON The Prose Edda Norse Mythology Translated with an Introduction and Notes by JESSE L. BYOCK PENGUIN BOOKS PENGUIN CLASSICS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Group (USA) Inc., -

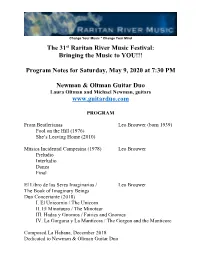

Program Notes for Saturday, May 9, 2020 at 7:30 PM Newman

Change Your Music * Change Your Mind The 31st Raritan River Music Festival: Bringing the Music to YOU!!! Program Notes for Saturday, May 9, 2020 at 7:30 PM Newman & Oltman Guitar Duo Laura Oltman and Michael Newman, guitars www.guitarduo.com PROGRAM From Beatlerianas Leo Brouwer (born 1939) Fool on the Hill (1976) She’s Leaving Home (2010) Música Incidental Campesina (1978) Leo Brouwer Preludio Interludio Danza Final El Libro de los Seres Imaginarios / Leo Brouwer The Book of Imaginary Beings Duo Concertante (2018) I. El Unicornio / The Unicorn II. El Minotauro / The Minotaur III. Hadas y Gnomos / Fairies and Gnomes IV. La Gorgona y La Mantícora / The Gorgon and the Manticore Composed La Habana, December 2018 Dedicated to Newman & Oltman Guitar Duo Commissioned by Raritan River Music With the generous support of Jeffrey Nissim CYBERSPACE PERMIERE PERFORMANCE Composed in celebration of the 80th Anniversary Year of Leo Brouwer NOTES IN ENGLISH CAPTURING THE IMAGINARY BEINGS BY LAURA OLTMAN AND MICHAEL NEWMAN The guitar explosion in the United States in the 1960s was fueled by the influence of Cuban musicians, including the legendary Leo Brouwer, as well as Juan Mercadal, Elías Barreiro, Mario Abril, and our teachers Alberto Valdes Blain and Luisa Sánchez de Fuentes. We grew up playing the music of Leo Brouwer. In the early days of the Newman & Oltman Guitar Duo, we shared a booking agent with Brouwer, Sheldon Soffer Management. We often thought that a major duet by Maestro Brouwer would be a dream for our duo. We met Brouwer at his New York debut recital in 1978, which was co- sponsored by Americas Society.